I remember when I first started incorporating orthography into my lessons. I was kind of panicky about having to be absent and needing to leave plans. How could I create a worthy activity, and then give the substitute teacher enough background information to lead it? Would opportunities for rich discussion go unnoticed by a teacher without real understanding of English spelling? The nagging answer to that question was, “Of course they would.” And because I couldn’t stand the thought of those teachable moments dissipating without notice, I left plans for other subjects, but not for orthography.

It didn’t take long before I felt guilty about that. I mean, studying orthography has become the most important subject I teach! Surely there were some activities I could put together that would keep my students thinking about words with or without me. Over the years I have repeated several of the activities that I found worked well. Just as importantly, I have learned how to set my lessons up for the substitute. I include notes on what to say as the activity is introduced and also on what to expect from the students. Recently I was absent for three days in a row. I thought I’d share the activities I planned for those absences along with my reflections of the student work (which always results in ideas of what to do next).

Being gone for three days is unusual for me. So what to leave for the students to do? I wanted to vary the activities so that they weren’t doing the exact same things each day, yet I wanted to reinforce the idea of a word’s morphemic structure.

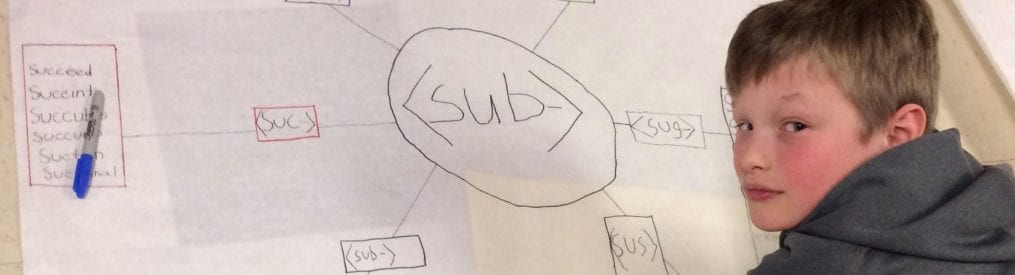

DAY ONE

10:05-10:35 Orthography

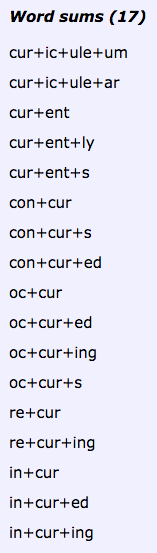

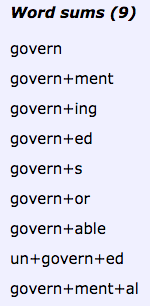

Write the word <make> on the board. Have students get a piece of lined paper from the shelf near the door. They are to put their name in the upper right corner of the paper. They are to write the word <make> on the top line of their paper. Then they are to write the words you read aloud as word sums. We have done this several times, so they know what to do. Remind them they are to write synthetic word sums for each word you read. Ask someone to explain to you what a synthetic word sum is. Ask them to skip a line on their paper between each word sum. Here are the words to read. Use them in a sentence if you can think of one.

maker

making

remake

makeup

filmmaker

troublemaker

makeover

Next, ask someone to collect the papers. As they are being collected, ask for volunteers to write the word sums for each word on the board. Here is what the word sums should look like (although please don’t correct anyone as they are writing them up):

make/ + er → maker

make/ + ing → making

re + make → remake

make + up → makeup

film + maker → filmmaker

trouble + maker → troublemaker

make + over → makeover

Once all the word sums are on the board, ask the class if they question anything that’s on the board. If there are questions, hear them out and ask what others think of the point being raised. Once everyone is in agreement over the word sums, ask for volunteers to read each word sum. They should be read as follows:

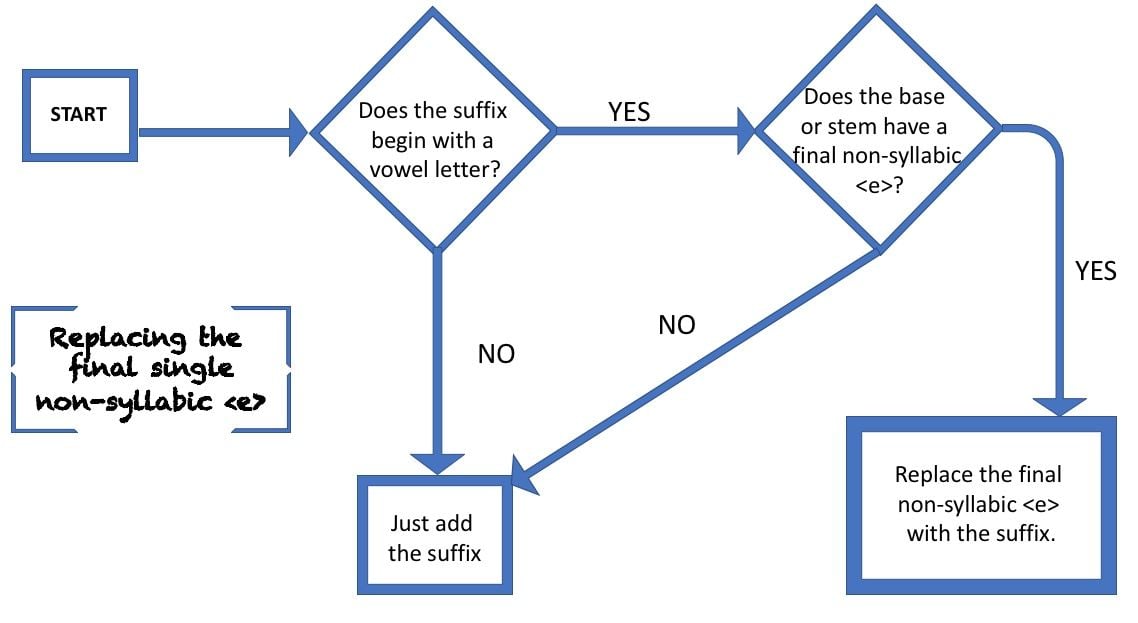

“M-a-k-e plus e-r is rewritten as m-a-k (replace the e) e-r.” Ask the student reading the word sum why the final non-syllabic <e> is replaced. I am hoping they say something like, “it is final and non-syllabic AND the suffix begins with a vowel”.

“M-a-k-e plus i-n-g is rewritten as m-a-k (replace the e) i-n-g.” Ask the student why the final non-syllabic <e> is replaced. I am hoping they say something like, “it is final and non-syllabic AND the suffix begins with a vowel”.

“R-e plus m-a-k-e is rewritten as remake”. Ask why we don’t replace the final non-syllabic <e>. I am hoping they say, “we are not adding a suffix”.

“M-a-k-e plus u-p is rewritten as m-a-k-e-u-p”. Ask why we don’t replace the final non-syllabic <e>. I am hoping they say, “we are not adding a suffix. We are adding another base and making a compound word. We only apply suffixing conventions when we are adding suffixes”.

“F-i-l-m plus m-a-k-e plus e-r is rewritten as f-i-l-m-m-a-k-e-r”. Ask why we replace the final non-syllabic <e> on <make>. I am hoping they say, “because the e is final and non-syllabic AND the suffix begins with a vowel”.

“T-r-o-u-b-l-e plus m-a-k-e plus e-r is rewritten as t-r-o-u-b-l-e-m-a-k-e-r”. Ask why we replace the final non-syllabic <e> on <make>. I am hoping they say, “because the e is final and non-syllabic AND the suffix begins with a vowel”.

“M-a-k-e plus o-v-e-r is rewritten as m-a-k-e-o-v-e-r”. Ask why we don’t replace the final non-syllabic <e> on <make>. I am hoping they say, “because we are not adding a suffix. We are adding another base and making a compound word, so the suffixing conventions can’t be applied”.

Save the stack of papers that was collected so I can look them over.

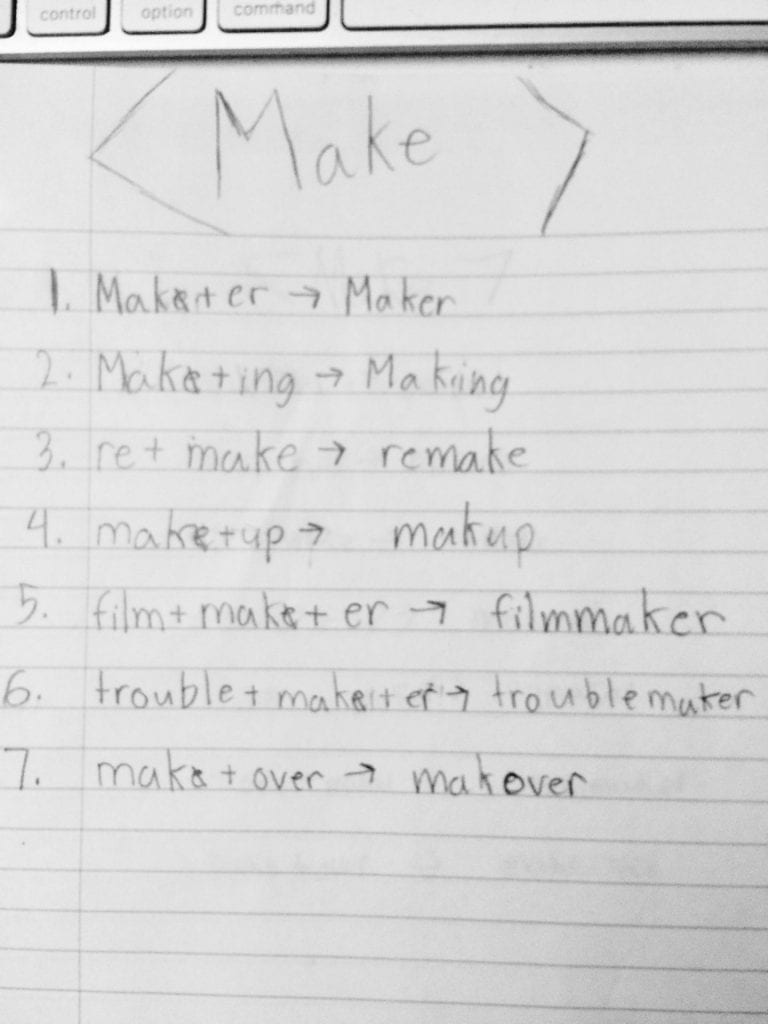

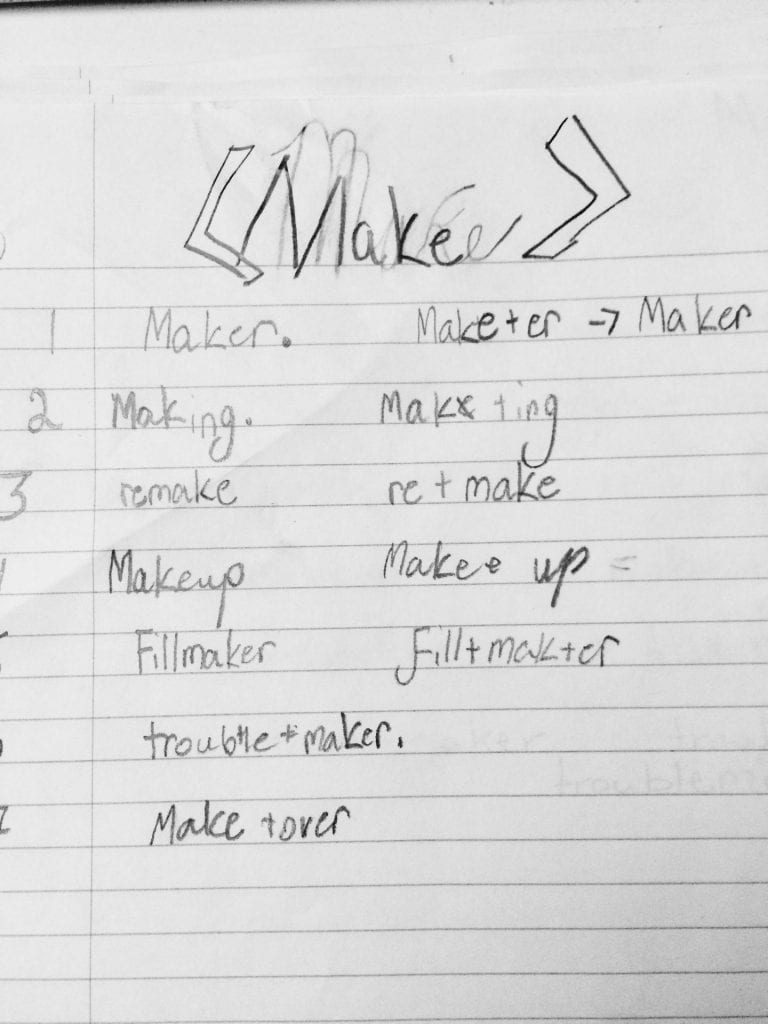

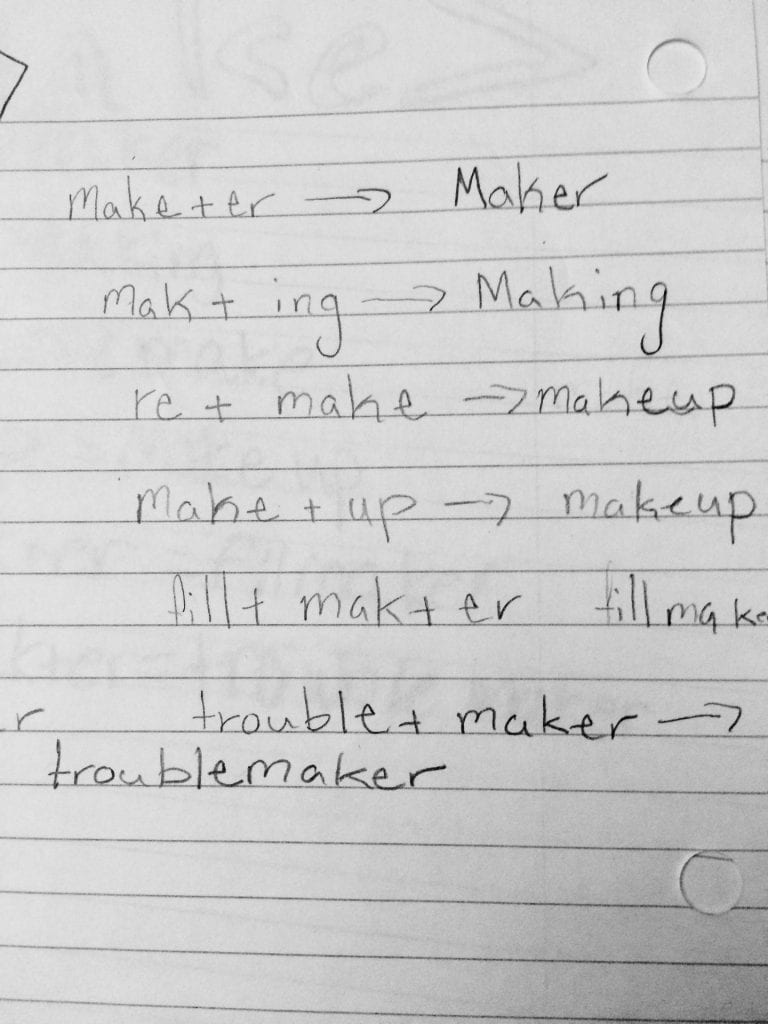

This is an activity I do fairly often with my classes. I get some valuable information from the student work, such as whether or not students recognize certain suffixes and/or suffixing conventions. Here are a few examples of what the student papers looked like.

Looking at this first sheet, I realized we would need to address the random capitalization of <maker> and <making>. I notice each year that students come in capitalizing certain letters whether or not it is warranted. The next thing I notice is that although this student understands that the single final non-syllabic <e> in the word <make> can be replaced when followed by a vowel suffix, they are not recognizing that <up> is not a suffix here. It is another base element and this word is a compound word. This student did the same thing with the word sum <make + over>. The suffixing conventions apply when a suffix is joined to a base, when a suffix is joined to another suffix, and sometimes when a connecting vowel is joined to a base.

Looking at this sheet, I see that this student is not writing out a full word sum for each word. I will need to explain again how writing word sums will help them as spellers. It will get them in the habit of thinking of words as elements that join to form a word, and that the word’s specific meaning is represented by the sense and meaning of the specific combination of elements.

Another thing to note is the unfamiliarity of the word <filmmaker>. We will need to talk about what a filmmaker is (in case the substitute did not catch this or address it). One last thing I see here is the word sum for <troublemaker>. I’m pleased that this student recognizes that in some words, <-le> is a suffix. Some examples are <sparkle>, <single> (from Latin singulus “one, individual” – not related to Old English singan “to chant, tell in song”), and <nestle>. We’ll have to look at <trouble> together to find out if this is one of those. Better yet, perhaps I can send each student (or each two students) on an investigation of a word with a final <le> spelling. Then we could compile our findings and see what we notice. Is it always a suffix? Is it sometimes a suffix? Is it rarely a suffix?

Looking at this paper I’m curious about the shifting spelling of the base element we are focusing on here – <make>. This student is not consistently recognizing the spelling of the base as <make>. This seems to happen when a student has learned the spelling of a word like <making>, but never really understood its structure.

DAY TWO

10:05-10:35 Orthography

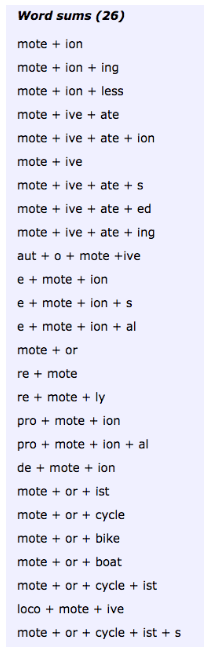

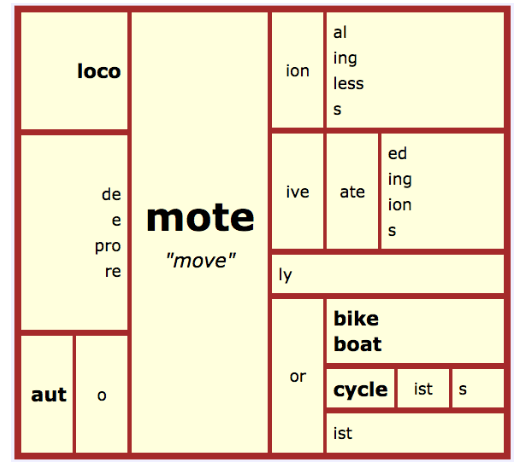

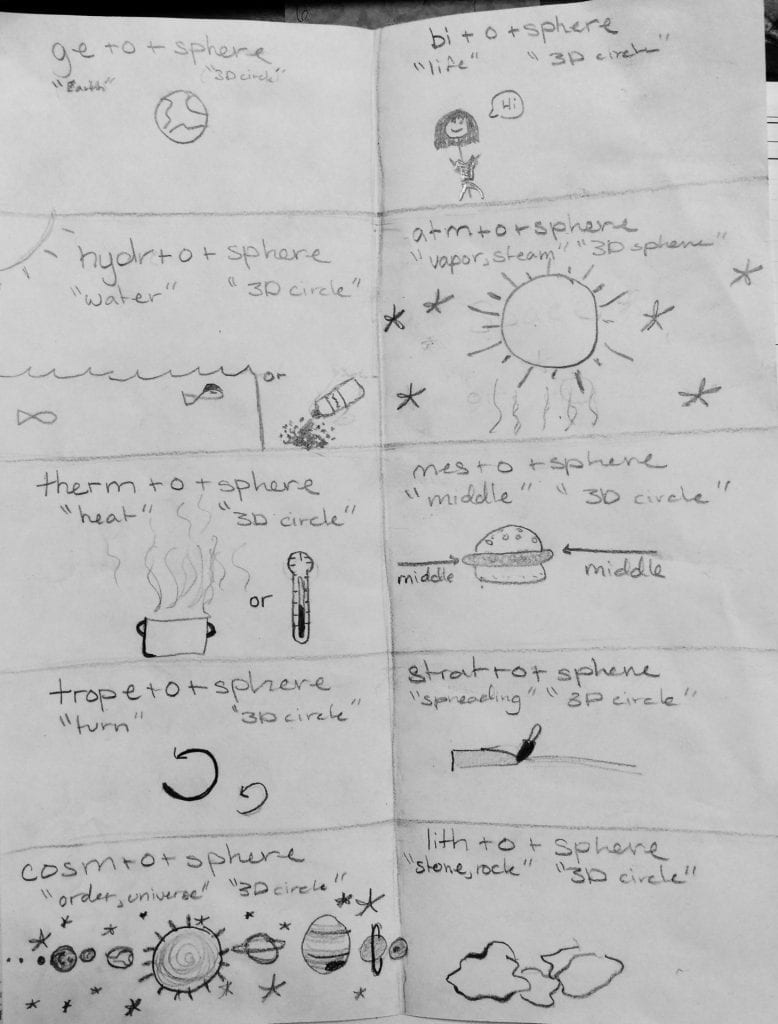

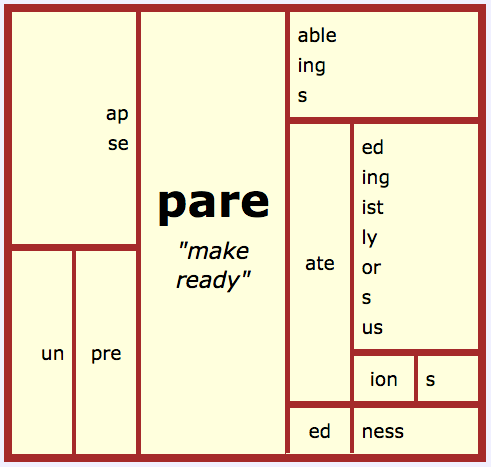

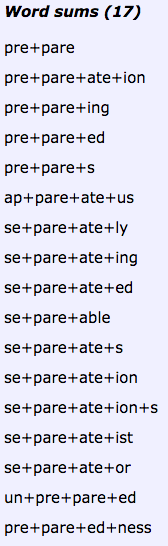

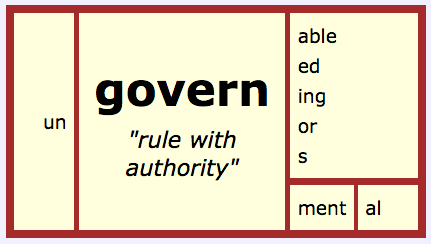

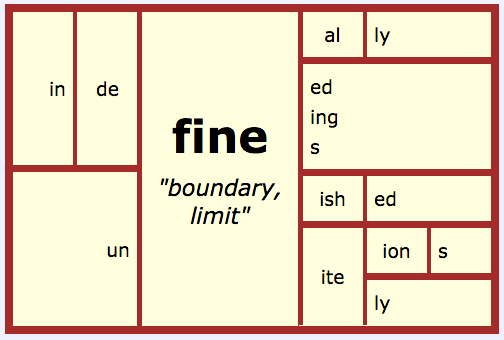

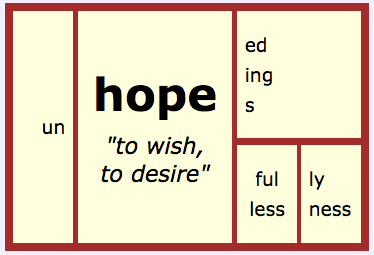

Arrange the students in groups of two. Make sure you have one copy of the matrix sheet for each pair of students. They are to work together to list word sums for words that could be made using the matrix. I’ve included (for you) the list I used when I created the matrix. Put the example word on the board and ask a student to explain it. (I am unable to put the slash through the final <e> in the word sum when typing, so it appears behind it. It should go through the <e> to show I am replacing that <e> with a vowel suffix. Most students can explain this to you.)

Have someone read aloud the directions, and then please ask if there are any questions about those directions. After that, they may begin. I’d like these turned in before they go to the next class. Save the stack of papers that was collected so I can look them over.

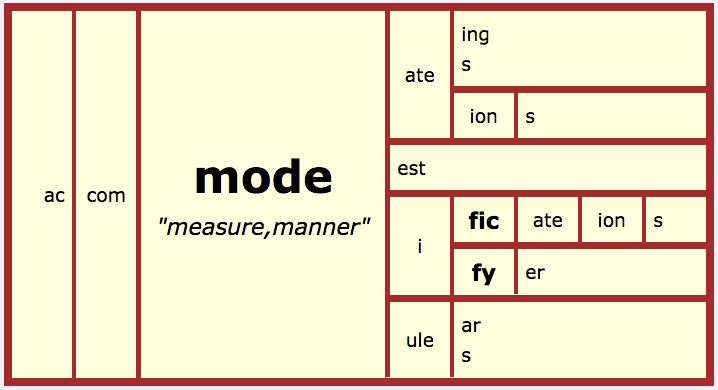

Here is the matrix sheet the students used:

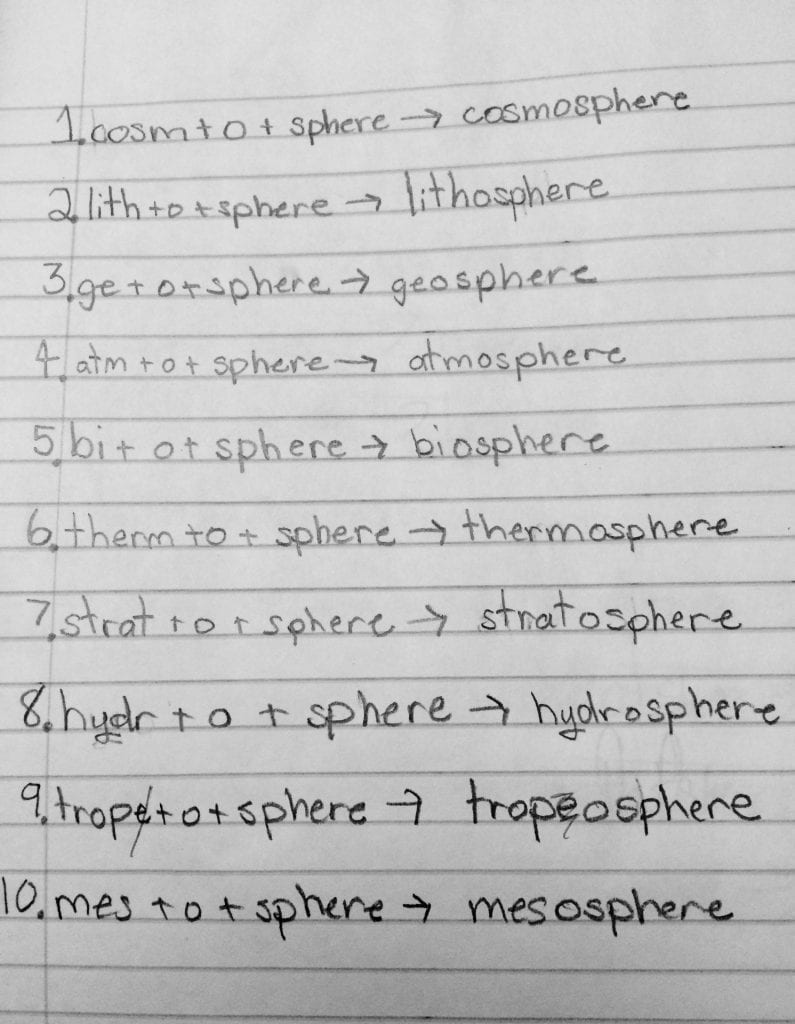

Here is a matrix for the bound base <mote>. Remember that we call this kind of a base a bound base because it isn’t a word by itself. It is ALWAYS bound to another element (a suffix or a prefix or another base). I’d like to see how many words you and your partner can recognize and write word sums for. Make sure your word sum looks like the example below:

mote/ + ive/ + ate → motivate

- Make your list on lined paper.

- Put both your name and your partner’s name on the top.

- Skip every other line. Take turns writing the word sums.

- Write neatly so I can read it easily.

- Once you are finished, read through your list together. Make sure you could use each word in a sentence. If you aren’t sure what the word has to do with “move”, look the word up in a dictionary.

- Turn your sheet in to the teacher.

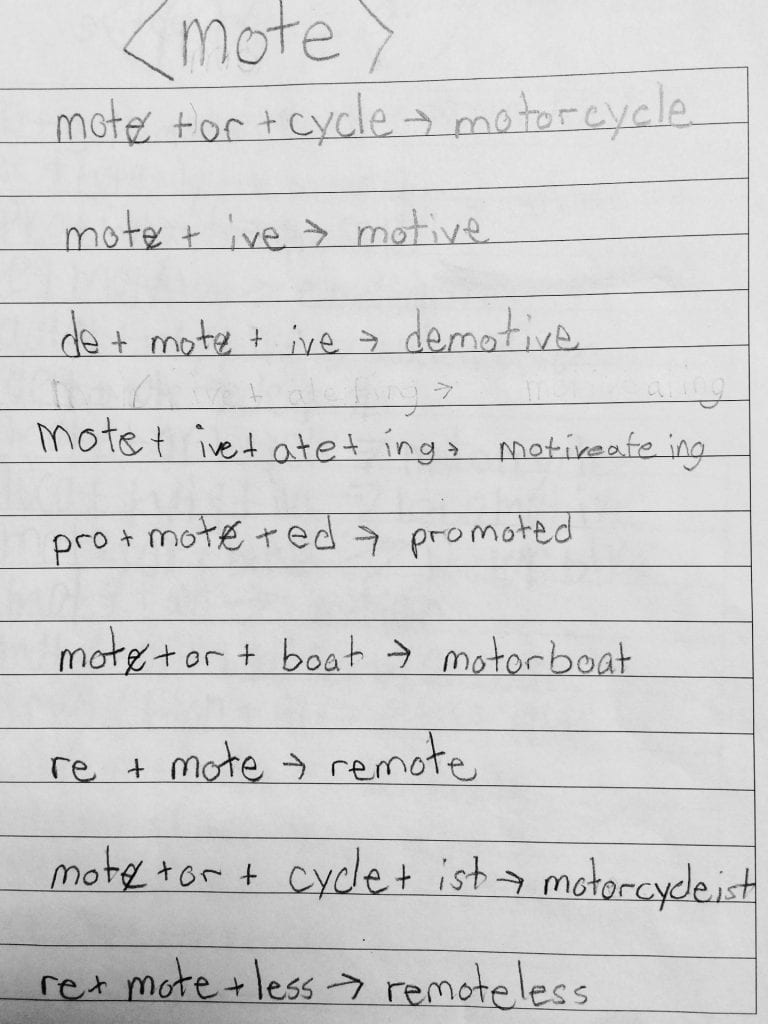

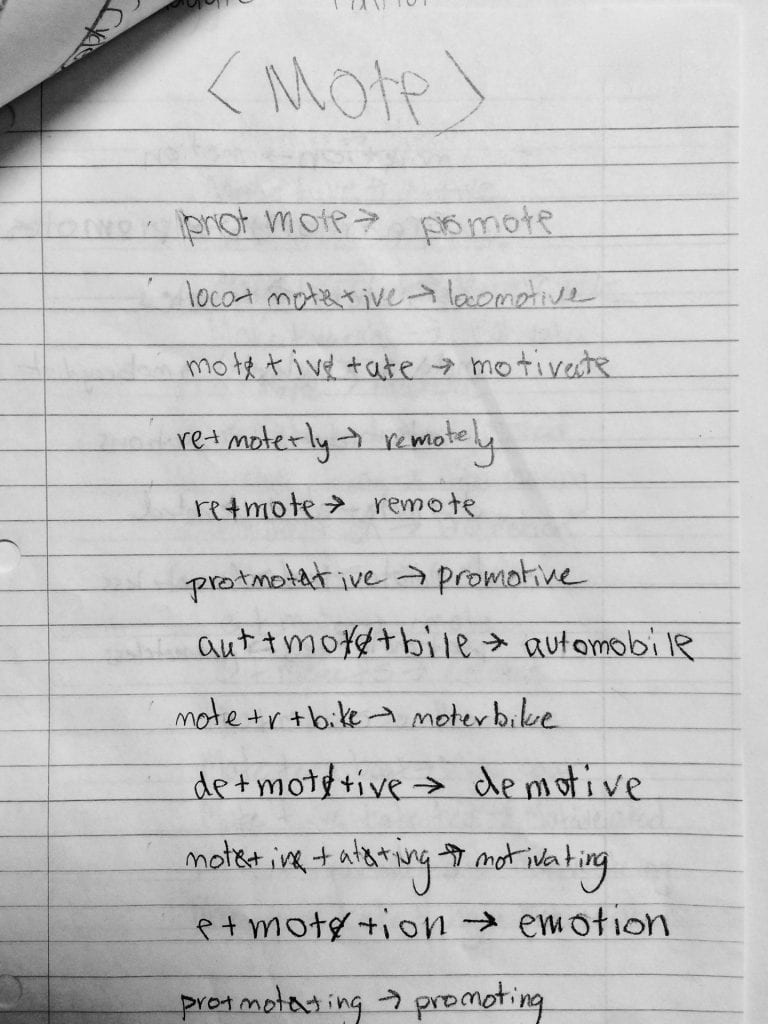

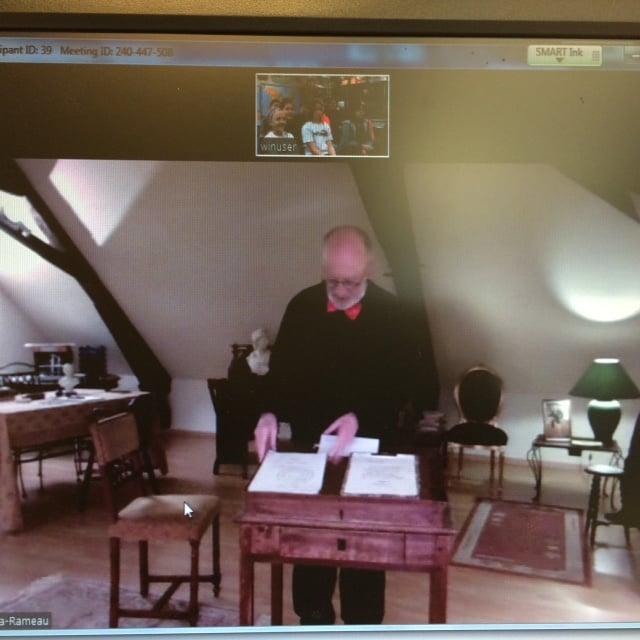

I wanted the students to work in partners because we had not done this particular activity before and I thought that two sets of eyes would keep the activity going. The substitute teacher said that she let the students in the second group (I teach three groups of 5th graders each day) know the largest number of words found by the first group. Then she did the same for the third group. The slight bit of competition kept students focused. Here are a few of the student papers:

What I learned from this paper is that the students understand the suffixing convention of replacing the single, final non-syllabic <e> when the suffix is being added to a base element, but don’t realize that the same convention is applied between two suffixes as well. I notice this in the word sum for <motivating>.

Something else that is interesting to note is the word <demotive>. When the students create a word like this, I love to point out its structure. We can make sense of this word’s structure, but can we make sense of its meaning? So next I ask them to use it in a sentence. If they can use it in such a way that we all understand what it means, then we call it a word. We do this whether or not the word is listed in a dictionary. These become our two criteria for whether or not we can call something a word. Does it have a structure that we can identify through looking at its morphological relatives? Can we use it in a way that other people understand what it means?

With the word <motorcyclist>, I need to reinforce the idea that <-ist> is an agent suffix. I’ve mentioned it before, but there is so much new information that I’ve presented since the beginning of the year that much of it needs to be repeated! It indicates that this noun refers to a person who is driving a motorcycle. We might then brainstorm some other words with this same agent suffix (chemist, scientist, artist, cellist, pianist, etc.).

On a day that I am directing their attention to <-ist>, I might also direct their attention to <-er> which can also be an agent suffix. After we have brainstormed a list of words with an <-ist> suffix, we will brainstorm a list of words with an <-er> suffix. Then we might sort those into lists of words that refer to a person and words that do not. Examples of words with the agent suffix <-er> are teacher, baker, driver, potter, gardener, and painter. Examples of words with an <-er> suffix that are not referring to a person are bigger, wiser, tower, paper, water, and outer. We might take the second list and divide the words up further by thinking about which of those words are used when comparing one thing to another and which just name things.

Look at what this group did! They knew there was a meaning connection between automotive and automobile, so they tried to make automobile fit this matrix! Interesting! This tells me that some of my students are still unclear about letters that we replace. We only replace single, final non-syllabic <e>’s. We don’t replace consonants! They are starting to see that our language is orderly and can make sense, but there are still lots of moments when they fall back into crossing off and adding letters willy-nilly because spelling has always felt that way to them.

The word right below automobile is also interesting. The students saw the single final non-syllabic <e> on the base and thought that just adding an <r> would work. They didn’t recognize that this word actually took an <-or> suffix. They also did not recognize that there is an <-er> suffix, but not an <r> suffix. This distinction could be made clearer if we spent some time brainstorming words with an <-or> suffix versus words with an <-er> suffix. In the past when I’ve looked at these suffixes with my students, we’ve noticed that many bases that can take an <-or> suffix also can take an <-ion> suffix. Examples are motor/motion, equator/equation, tractor/ traction, reactor/reaction, and director/direction. An activity like that can be done as a whole class if everyone is looking at Word Searcher and thinking about the words listed that have an <-or> suffix. How many of them might take an <-ion> suffix, and how many can’t?

The substitute teacher on this day was not the same one as the day before. This one wasn’t any more familiar with orthography than the first one. Even so, she personally enjoyed the activity. I later found a list of words she made by using the elements on the matrix. She had 39 words on her list! I especially loved the note she left me:

Looks like my lesson made an impression on her as well as my students!

DAY THREE