My students enter fifth grade with limited knowledge of words. They know a fair amount of words, but they don’t really know much about them. They think that learning to spell a word is unrelated to learning what that word means. According to the students, those are two skills done at two different times. They have no idea that words actually carry meaning in their elements … because they don’t know that a word is composed of elements. In other words, they don’t know that words have structure. They don’t know that every word has at least one base element that supplies the main sense and meaning of the word. They’ve heard of prefixes and suffixes, but not of connecting vowels. And even though they’ve heard of prefixes and suffixes, they don’t know that a word can have more than one of either of those.

So how do I help?

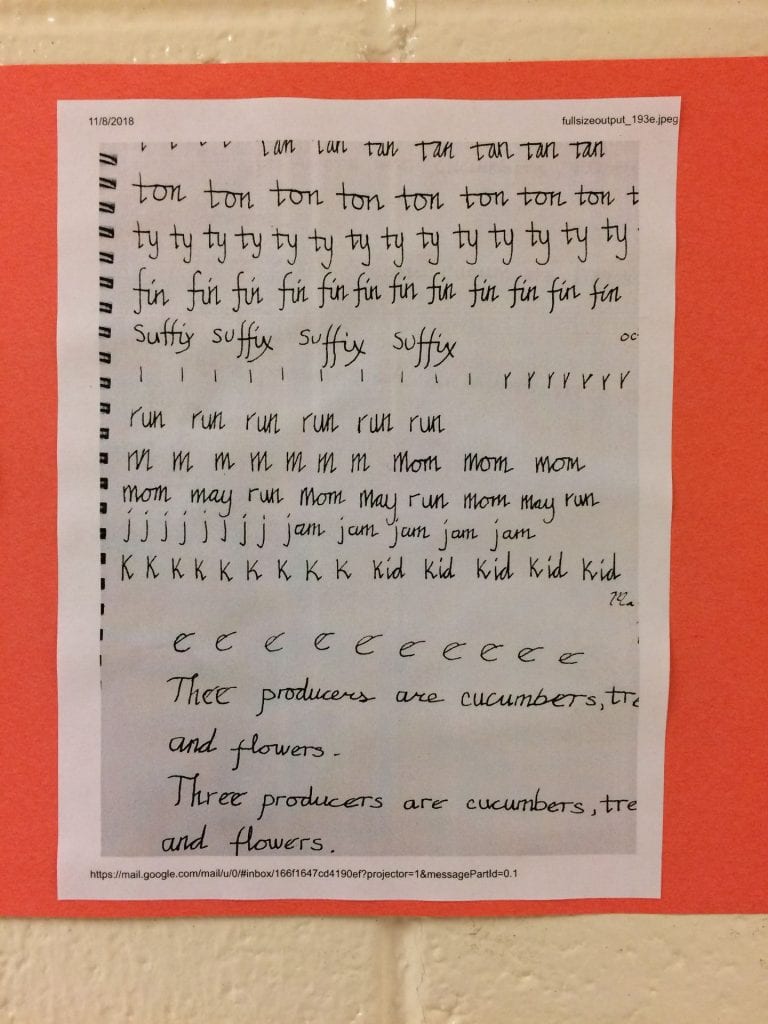

I keep thinking of activities that will help my students become more familiar with the elements in a word. I have shared many of those activities in other blog posts, but here is one that is new. This one focuses on suffixes and being able to prove whether or not letters at the end of a word are a suffix. I had the students work in pairs and use one Chromebook per pair. Before I gave them paper to write on, I had them open tabs at Etymonline and at Neil Ramsden’s Word Searcher. Then, as a class, we practiced using these two resources to find words with specific suffixes.

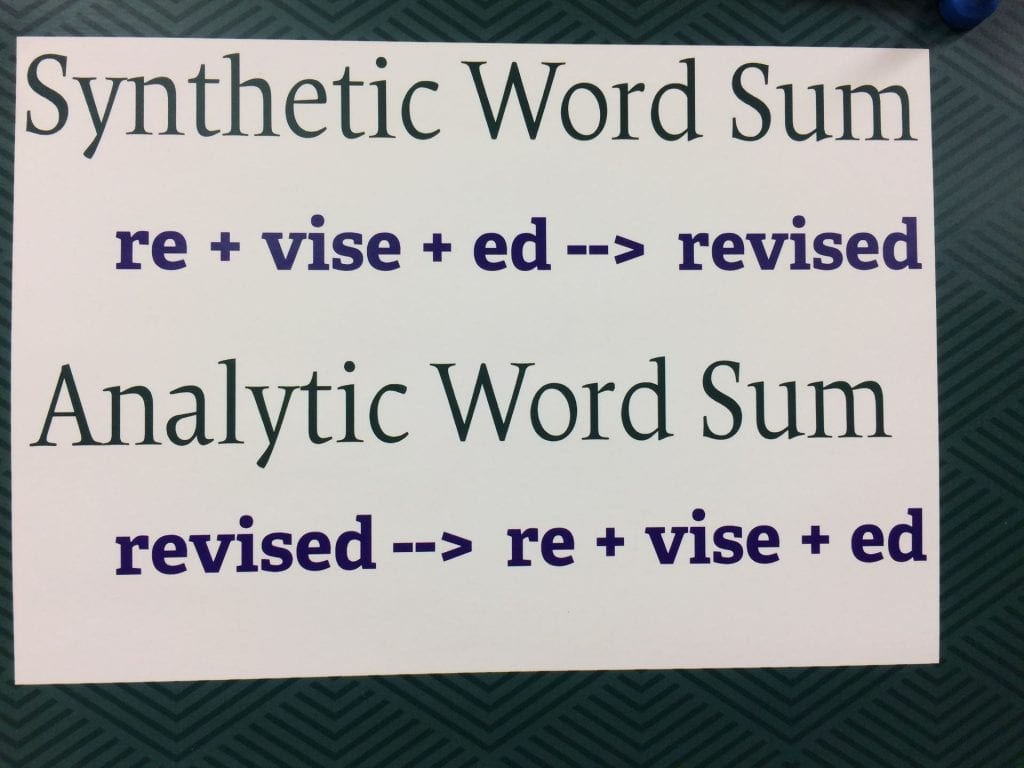

I had sheets of paper, each with a suffix at the top. The students were to find words that had that suffix. They were to write a synthetic word sum for each word they found. I felt that if they wrote a synthetic word sum, then they might quickly recognize whether or not the letters at the end of the word were truly a suffix or just part of the word. As an example of that, I wrote the word <jumping> on the board and asked if the <ing> in this word was a suffix. There was a resounding “Yes.” I asked for a word sum. A student replied, “<jump + ing –> jumping>. Great. Next I wrote <bring> on the board and asked if the <ing> in this word was a suffix. This time I had a mixed response. Some were definite in their voiced, “No.” Others quickly said, “Yes.”

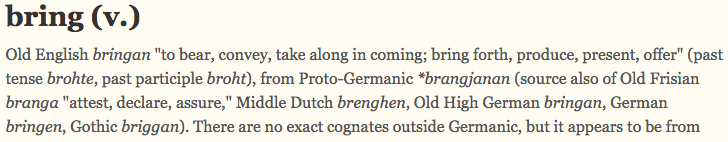

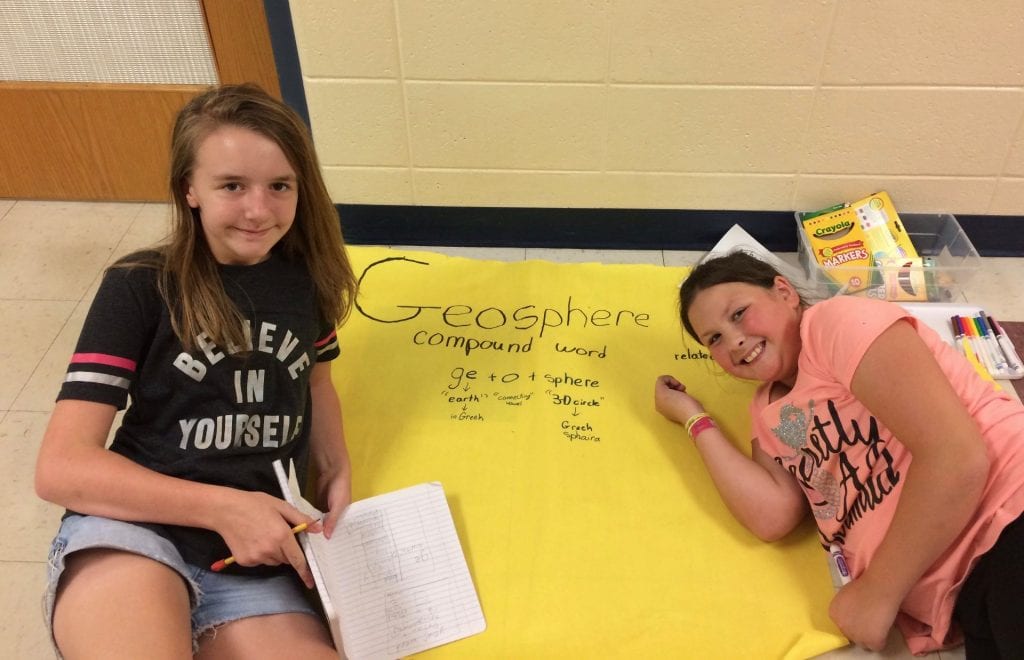

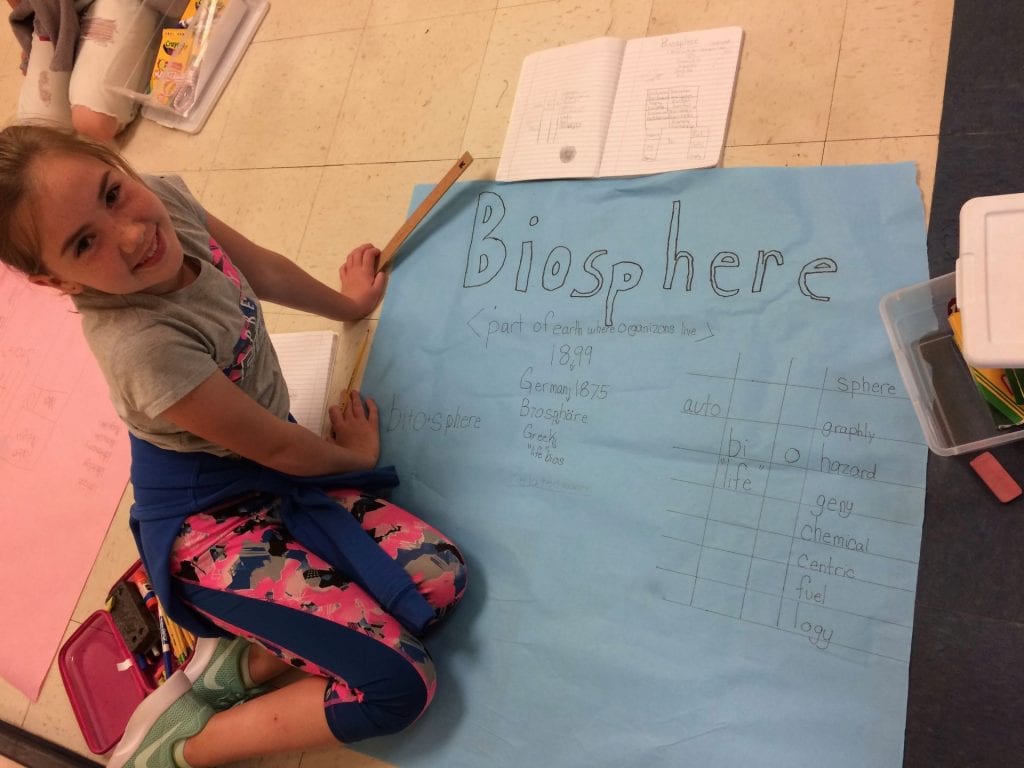

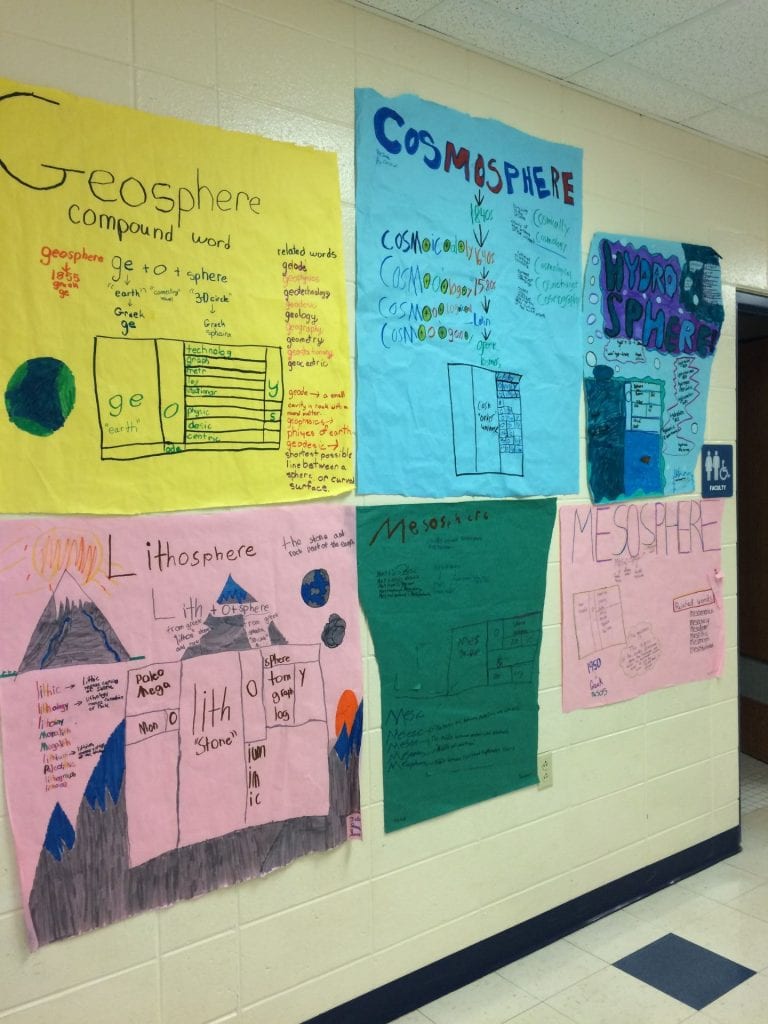

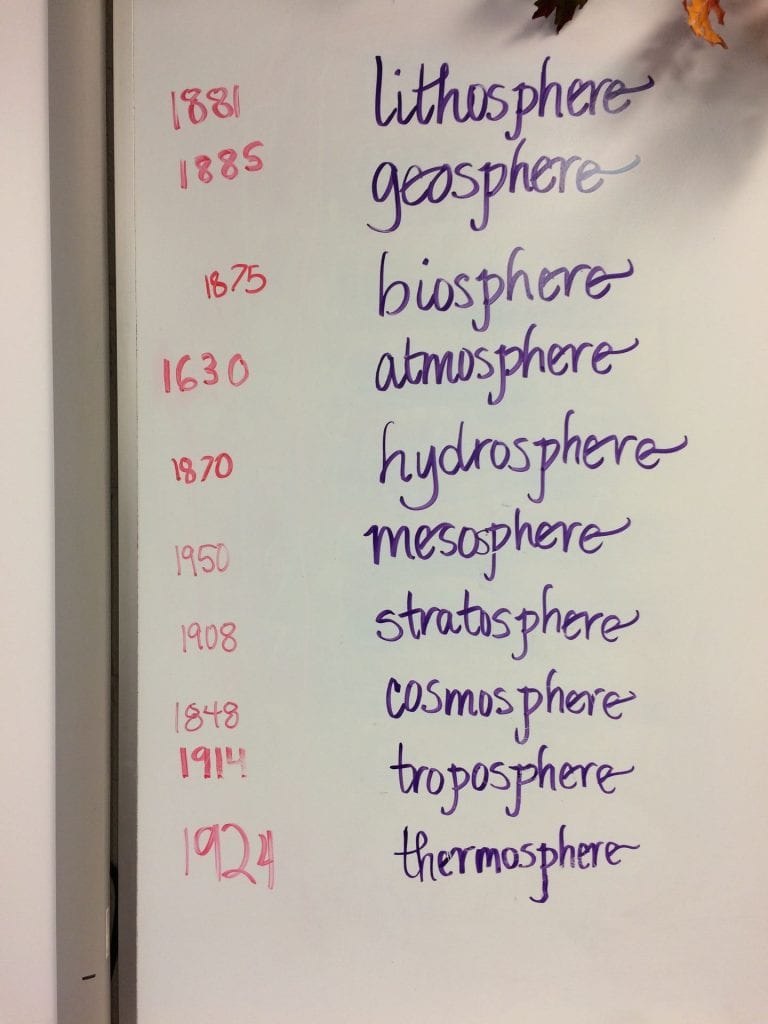

As we’ve been learning since the beginning of the school year, not all bases are easily recognized by people new to studying morphology. We recognize what we are familiar with. We are familiar with bases that are free, meaning we recognize that the <-ing> in <jumping> is a suffix because we recognize <jump> as a word we have been using for a long time. But earlier this year, as my students encountered words like <hydrant> and learned that the base was <hydr>, they began to wonder about these bound bases we come across in our investigations. When we looked at <biosphere>, they identified the two bases as <bi> and <sphere>. The first is a bound base from Greek bios “life, living” and the second is a free base from Greek sphaira “globe”. So in their limited experience, I have shown them that a bound base can be biliteral (consisting of two letters). So back to the word <bring>. Why wouldn’t some of the students be open to the fact that <br> might be a bound base? So instead of me telling them whether it is a bound base or not, I directed all the students to the entry for <bring> at Etymonline. Here is the part of that entry that we focused on for this activity:

We read it together looking for evidence that this word was from a root that became the Modern English two letter base element <br>, but we could not find any. The <ing> was always part of the spelling of this word. Therefore, we can conclude that the <ing> in <bring> is not a suffix.

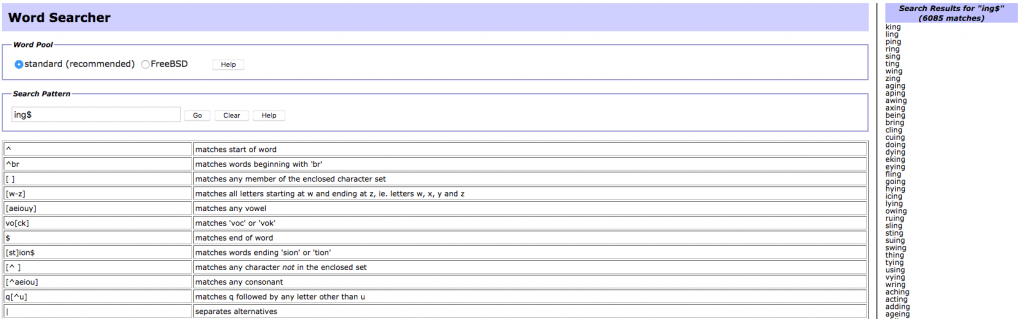

Next I directed them to Neil Ramsden’s Word Searcher and showed them how to search for words that end in <ing>. Using the legend below the search bar, I had them use the $ sign after the suffix so that only words with <ing> at the end of the word would show up. Then we looked at the list. Wow. There were 6085 words listed. “Does this mean that all of these words have an <-ing> suffix?” I asked.

“No!” replied one of the students. The word <bring> is on this list and we know that the <ing> in that word is NOT a suffix!”

“Right.” What I want you to do is read through this list and find words that you suspect have an <-ing> suffix. Then I want you to flip to Etymonline to check for evidence to help you in your decision making. Once you are confident that you have found a word with a clear <-ing> suffix, write the word as a synthetic word sum.”

I let them work with their partner for seven or so minutes before I interrupted them to begin the activity. “Now that you know what I expect you to do, let’s get started with today’s activity. I will give each group a piece of yellow paper. At the top of each sheet is a specific suffix. In this way, each group will be looking for words with a suffix that is different from every other group. After ten minutes of work time, I will come around and switch which suffix your group is looking for. In this way, I am hoping you become familiar with several suffixes.”

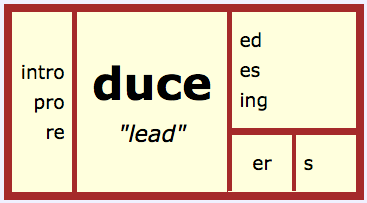

Here is a list of the suffixes I believe they already encounter on a daily basis:

<-s>

<-es>

<-ed>

<-er>

<-en>

<-ate>

<-ion>

<-est>

<-ist>

<-ous>

<-ing>

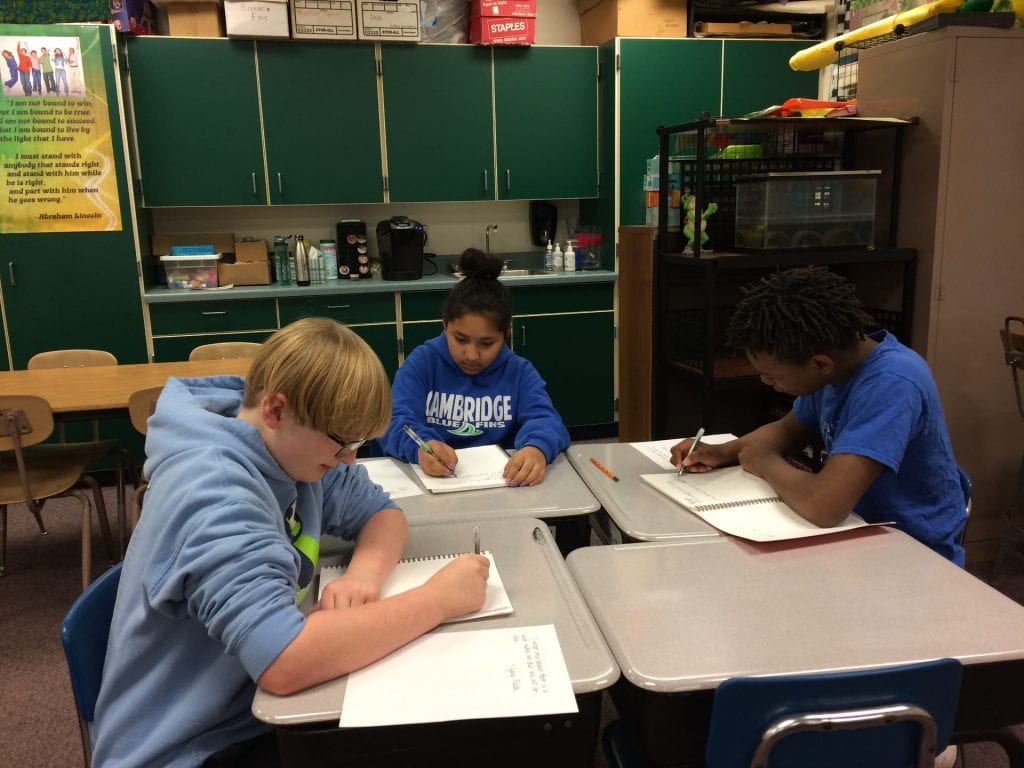

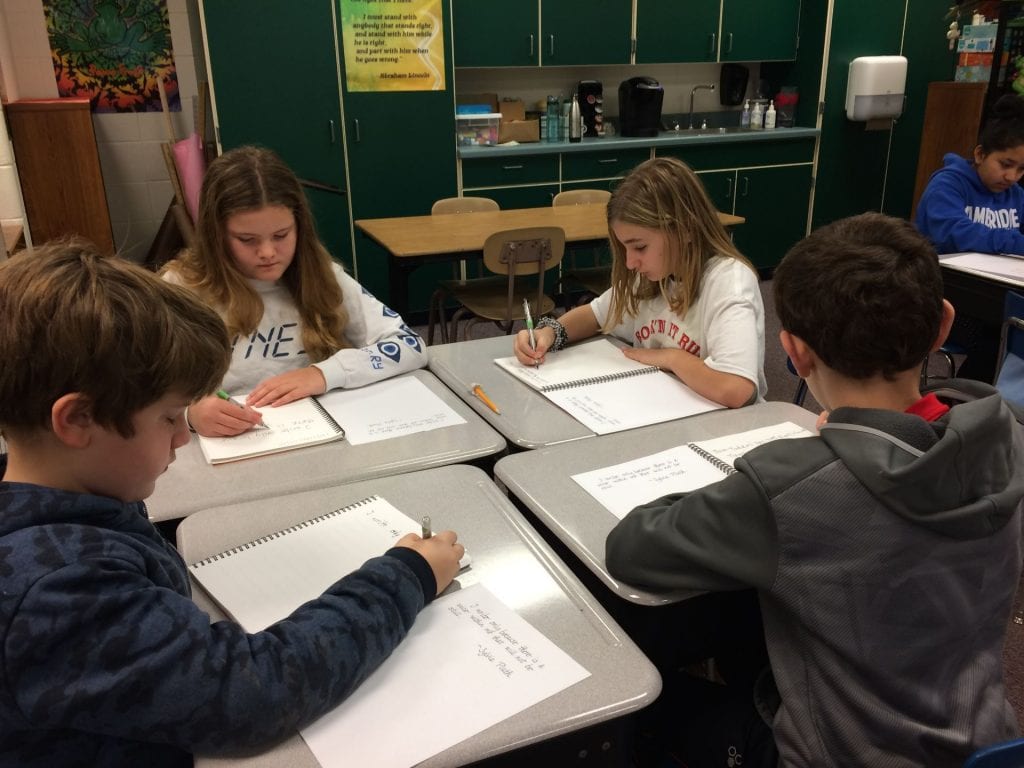

Do you see the kinds of wonderful discussions that could come of the lists they are creating? As the students got started, I walked around and listened in to make sure they were using the resources as intended rather than just guessing at words that might work. This activity went well. The students were engaged and enjoyed having a partner to think out loud with.

When it came time to switch the sheets to a different group, I asked that the first task be that the group read through the previously listed words. If the new group had questions about any of the words and its word sum, they were to put an asterisk to the left of the word. After that they could add to the list. On this particular day, we only switched twice.

<-s>, <-es>

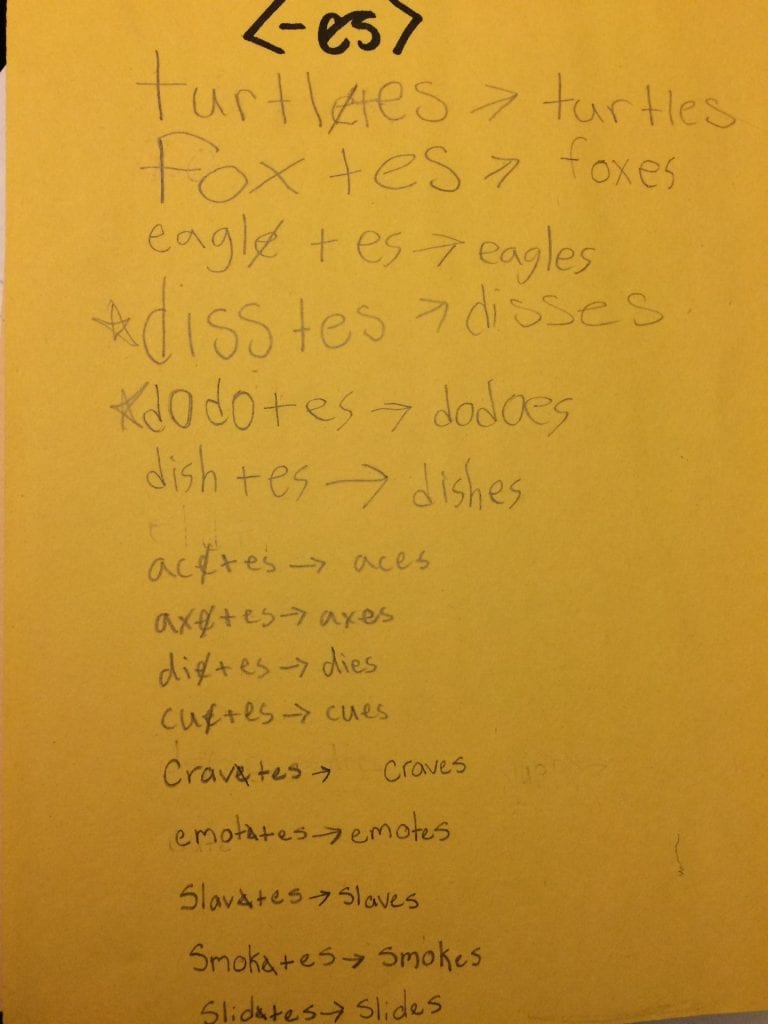

So let’s take a look at the sheets and see what there is to notice. One thing I was interested in finding out is whether or not my students understood when an <-s> suffix was used and when an <-es> suffix was used. So I compared the two sheets.

As you might expect, when the base had a final <e>, there was confusion. Is an <-es> the suffix to be added or an <-s>?

Looking at this sheet, it appears that many students are used to adding this suffix and understand that in most cases it represents marking a word as plural. The two words on this sheet that I would highlight to talk about would be <ages> and <lines>. Even though <lines> is a word with an <-s> suffix, because I also see <ages> on this list, I want to make sure my students can explain why <lines> has an <-s> suffix and<ages> has an <-es> suffix.

This sheet reveals a broad lack of understanding about the <-es> suffix. The students recognize that when an <-es> suffix is joined to a base that has a single final non-syllabic <e>, that final <e> is replaced by the suffix. That is a good thing. But it appears that they are using a single final non-syllabic <e> as a signal that the <-es> suffix is the one to use. Here’s where we need some clarification!

If I make two lists on the board like the two below, and ask my students to read them aloud, they no doubt would notice that the first list has one syllabic beat and second list has two.

fox foxes

dish dishes

ace aces

use uses

ash ashes

If they catch on to that, I would also present the following lists:

absence absences

excuse excuses

college colleges

memorize memorizes

surprise surprises

I would ask, “Is the same thing happening here? How many syllabic beats in <absence>? How many in <absences>?” I want them to notice that we use an <-es> suffix when making the word plural adds on a syllabic beat. I don’t want them to think this only applies to a base that has one syllabic beat to begin with.

Now I will present this next set of lists:

chicken chickens

toe toes

pencil pencils

desk desks

shoe shoes

Again we will count the syllabic beats and see if the plural form is one syllabic beat longer. They will notice that making the word a plural did not change the number of syllabic beats.

Here’s the next set of words to compare:

horse horses

promise promises

adjective adjectives

tadpole tadpoles

squeeze squeezes

The first thing I want the students to notice with this list is that all of the singular bases have a single final non-syllabic <e>. That will not help determine whether we use an <-s> suffix or an <-es> suffix. I will ask, “How do we know whether we have used an <-s> or an <-es> to make these bases plural?” Hopefully, at this point they can explain back to me that when a syllabic beat is added to the word when the word is in its plural form, the <-es> suffix is used.

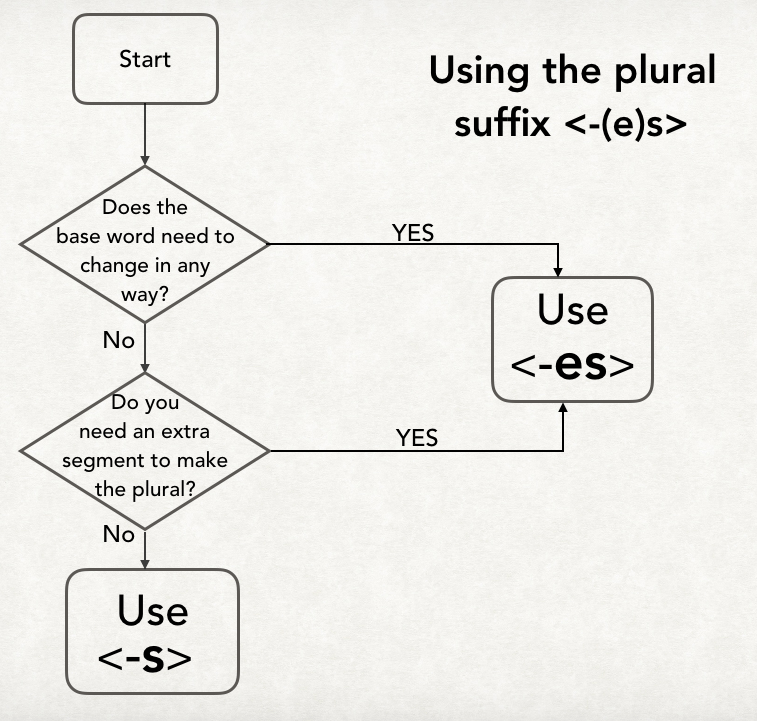

(The above flow chart is being used with permission from the works of Real Spelling. In the flow chart, an “extra segment” is what I have referred to as a “syllabic beat.” )

This discussion of <-s> versus <-es> is the place I will start with the students when I see them next. Then, once the students can state when to use an <-s> suffix and when to use an <-es> suffix, I’ll create an exit slip, asking the students to write down a synthetic word sum for both <ages> and <lines>. In that way I’ll be able to assess individual understanding between these two suffixes.

There are other instances of using an <-es> versus an <-s> suffix, but I will begin with the misunderstandings I have noticed in this activity. The other instances will come up in our work at another time. They always do!

<-ed>

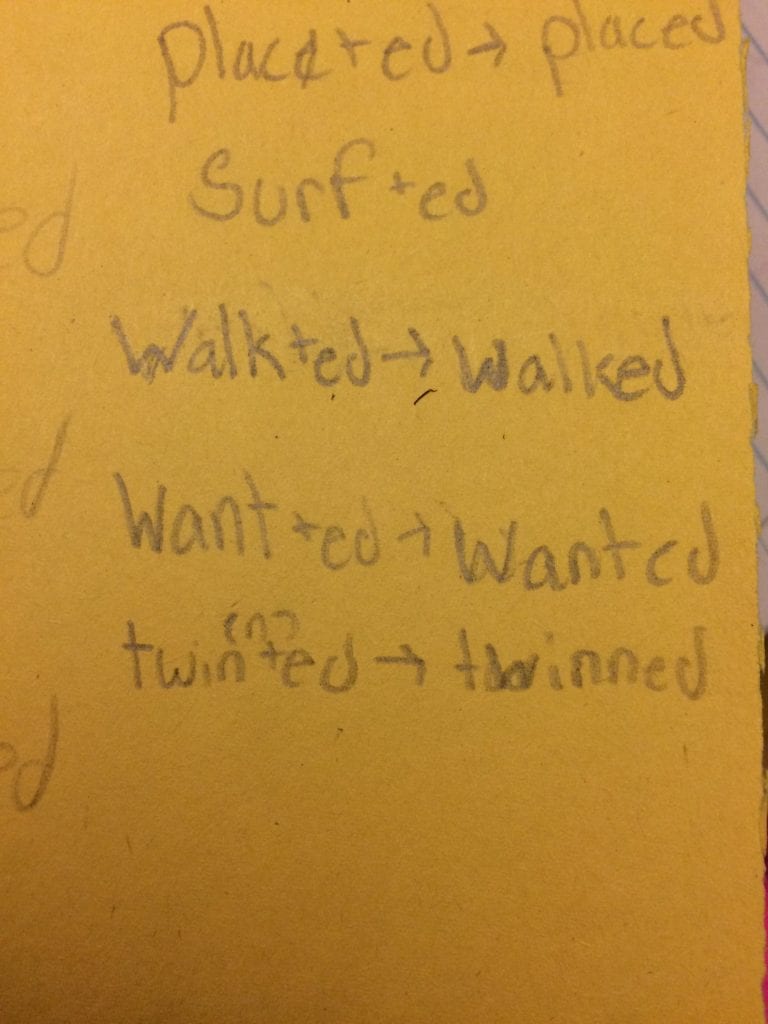

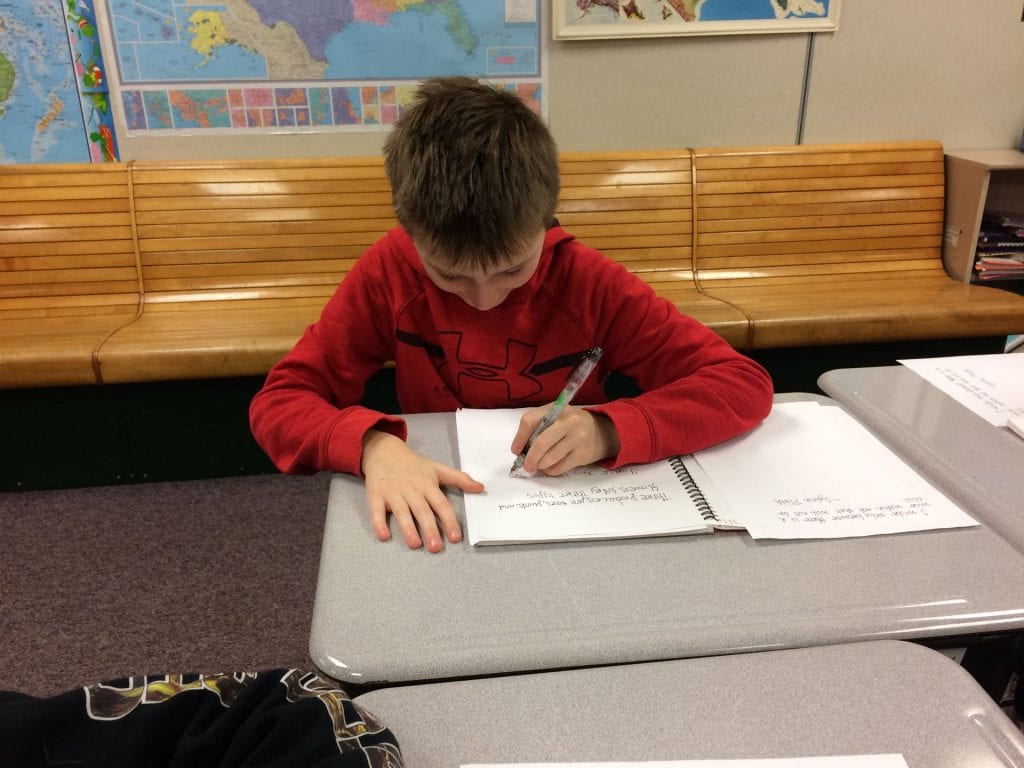

As I looked over the sheets for <-ed>, I noticed that a few need to review the suffixing convention that requires the final consonant of the base to be doubled when a vowel suffix is added. One group called me over and asked how to represent that happening in a word sum. They were writing a word sum for <twinned>. As you can see in the picture below, I showed them that on the left side of the word sum we do our thinking and analyzing. I said that other people might have another way to represent it, but I like to put the doubled <n> in parentheses close to where it will be in the final spelling.

Other than that, I was pleased to see that over and over students were showing that the single final non-syllabic <e> would be replaced with the <-ed> suffix. Our practice with that suffixing convention has paid off!

The expected use of a word with an <-ed> suffix is as a past tense verb.

Jane wanted a puppy.

Saveea walked to the store.

Landing awkwardly, he damaged his ankle.

But what if we use a word with an <-ed> suffix to modify a noun?

Her grandfather was a wanted man.

I took the well-walked path.

I returned the damaged package to the post office.

When looking at words on a list (as we are with this activity), it is important to be thinking of sentences in which we might use the words. The context is what defines a word’s function within any given sentence. Please keep that in mind. Have your students suggest the sentences so they become comfortable with changing the way a word functions within a sentence.

<-er>

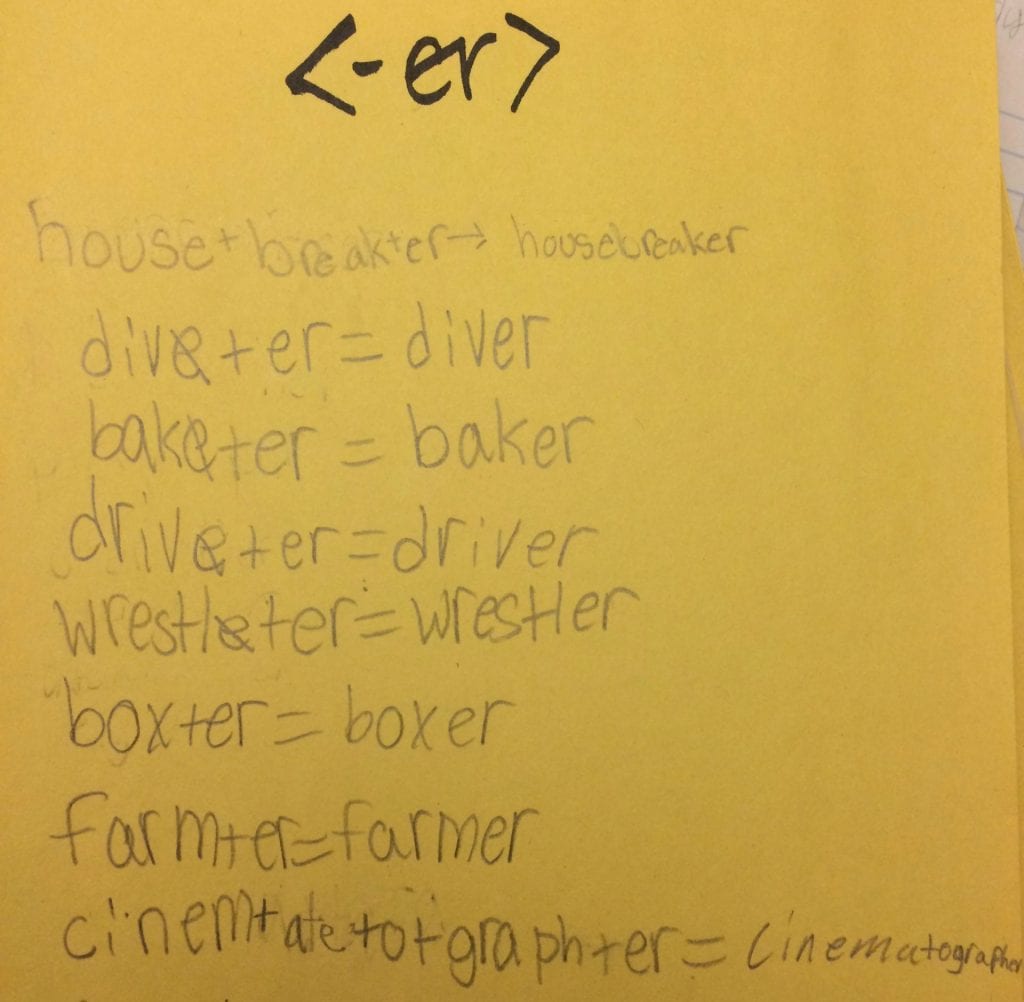

One of the drawbacks from an activity like this is that some children will do this on automatic pilot, meaning they will not think too deeply about what they are doing. One of the directions I had at the beginning was that the students couldn’t use a word that they didn’t know. In other words, I didn’t want them to just copy from the list at Word Searcher without knowing for sure whether or not the <er> was removable (a suffix). A word that I saw on the list with this suffix was <power>. It was on the list as *<pow + er –> power>. That just didn’t seem right to me, so I looked at Etymonline. I couldn’t find anything in the entry that pointed to this being a case of a base plus an <-er> suffix. Then I looked below at the listed related words and couldn’t find any words that had the <pow> spelling without the <er>. As far as this resource is concerned, <power> doesn’t have an <-er> suffix and should not be on this list.

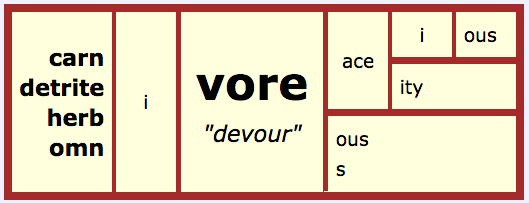

I must say I was pretty impressed with one group’s word sum for <cinema + ate + o + graph + er –> cinematographer> What impressed me is the fact that this group recognized the base <graph> that we have looked at a few times. They also recognized the possibility of an <o> connecting vowel!

One of the other things I’d like to do with these lists is to see if we can categorize some of them as to their grammatical function. We’ll have to be careful though. In order to determine a word’s part of speech, we’ll have to use the word in a sentence first. I was thinking of something like this:

1 2 3

Person Comparison Thing

baker fewer mower (depends)

diver ruder dryer (depends)

farmer slower sewer (depends)

wrestler older mixer (depends)

biker riper charger (depends)

If I wrote (depends) next to the word, that means the word could be a thing, but it might also be a person. The context (the sentence we find it in) will be what determines its meaning. I’m hoping the students challenge the lists and offer sentences to support their thinking!

Do you see how this might bring awareness of how this particular suffix is used? I can imagine some great sentences being offered and some questions being raised.

<-en>

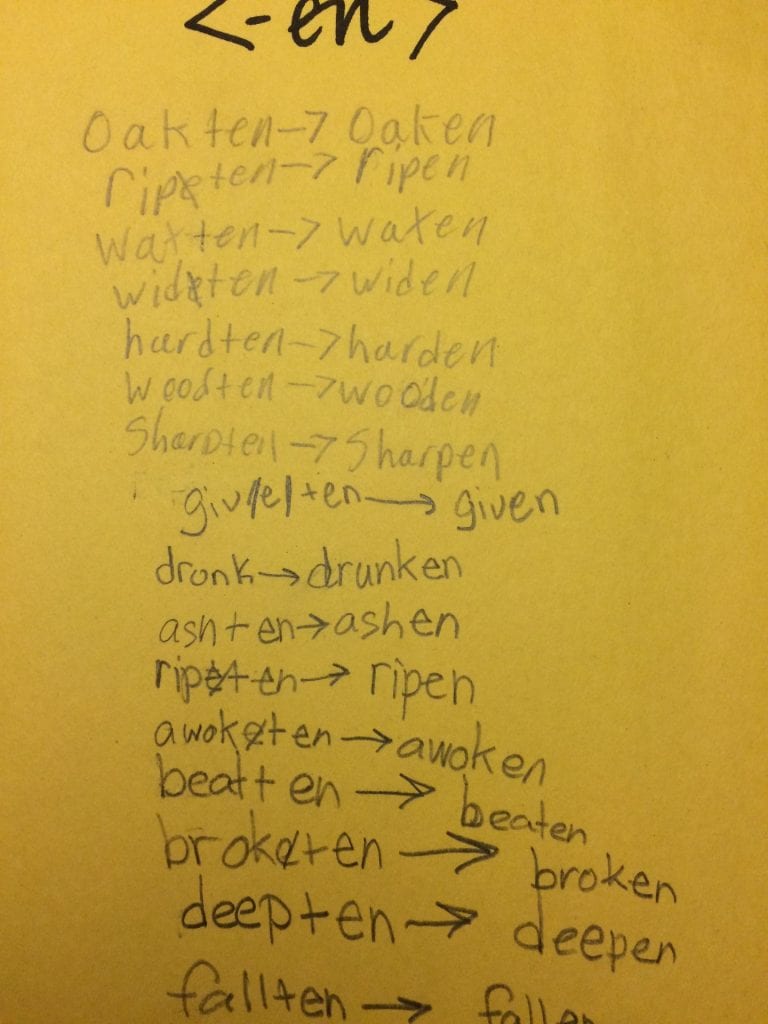

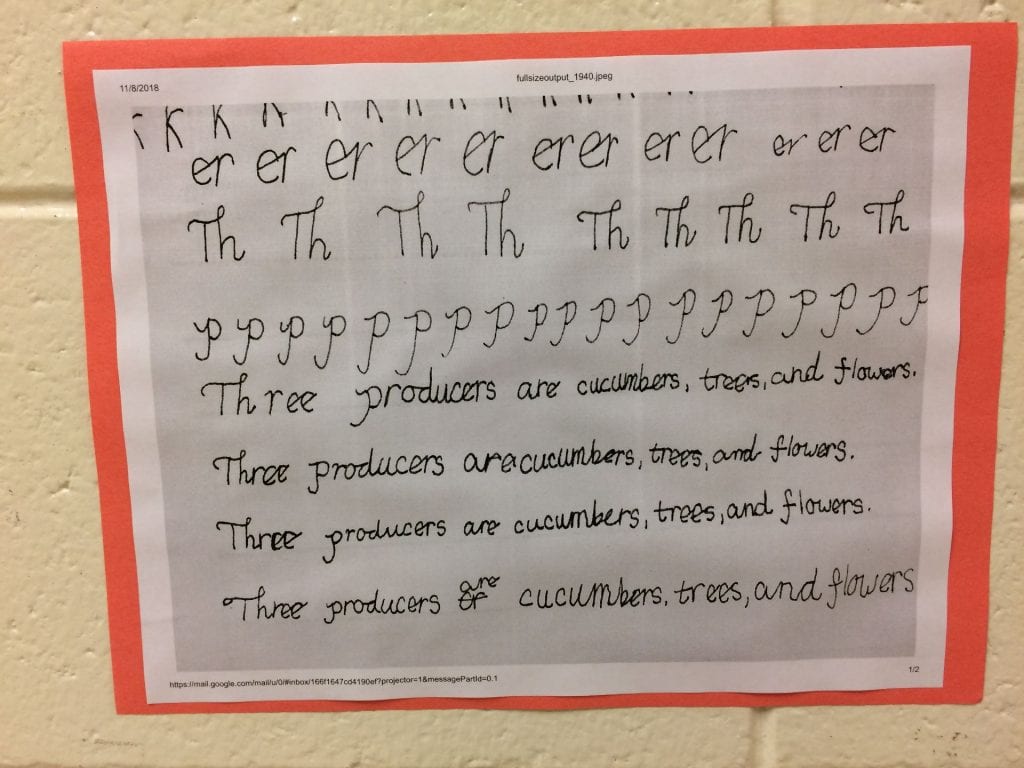

This suffix didn’t seem to present problems with spelling. Word sums were clearly written, and if there was a suffixing convention to be applied it was replacing the single final non-syllabic <e>.

I’m thinking of looking closer at these lists as well to examine how we use words with an <-en> suffix. Two categories that seem obvious are adjectives and verbs. At first glance I see words that can sometimes function as adjectives such as ashen, broken, frozen, widen, and wooden. Then I see words like ripen, sharpen, deepen, and flatten. These are verbs. As usual, context will be the thing that determines how a word is functioning.

adjective verb

ashen ripen

oaken sharpen

golden deepen

wooden flatten

I wonder how accurate my students would be at categorizing the words in this way. Perhaps I could give them a framework that would help. For the adjectives, I could tell them that if they say the word and can think of a noun it could modify, they can classify it as an adjective. As an example, let’s say, “frozen ….. pond” or “frozen food”. In this way the students know it can be an adjective because they have it modifying a noun.

One way to check to see if it could be used as a verb, would be to use the modal verb “will” in front of the word and see if that makes sense. For example, I could say, “will ripen”, as in “The banana will ripen.” We could also use the auxiliary verb “has” in front of the word. For example, I could say, “has broken”, as in “The boy has broken his ankle.”

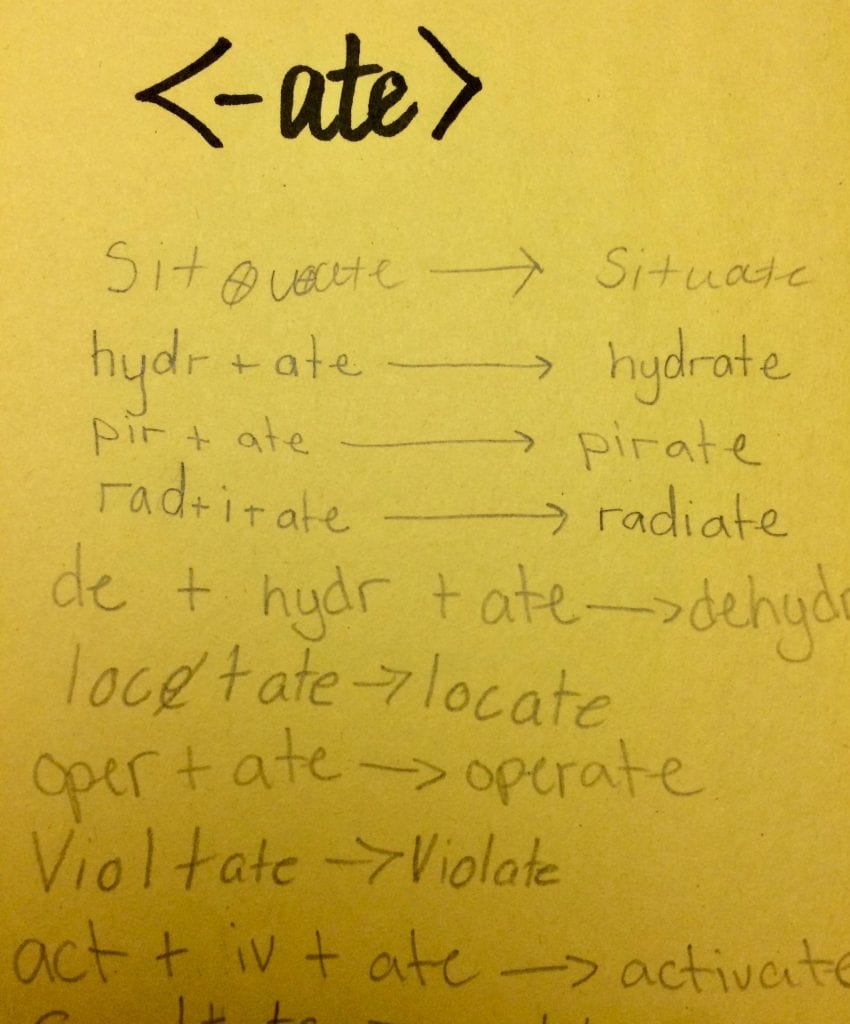

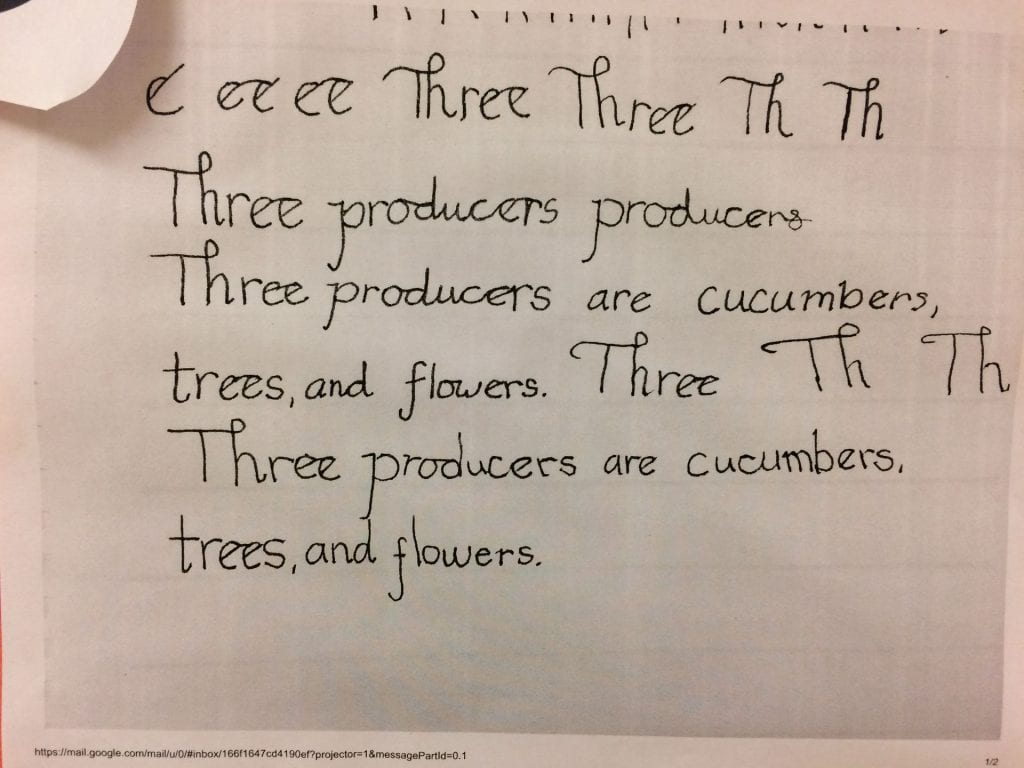

<-ate>

This sheet revealed different levels of understanding. The students are making hypotheses about the structure, and it is obvious that the hypotheses they are making are based on an understanding that is deepening with each classroom investigation. It is also obvious that not everyone is in the same place with their understanding. That is what makes classroom teaching so challenging and often rewarding!

I know that the use of the plus signs can be visually confusing at times. Some of the students do a nice job of leaving enough space between elements in the word sum. Others circle the plus signs so they don’t look like <t>’s.

In the word sum for <situate>, the students hypothesized that the <u> is a connecting vowel. Since the base is Latinate, that hypothesis is quite possible! The word sum for <hydrate> is one we know. When the students investigated <hydrosphere> earlier this year, they came across this relative and we talked about both <hydrate> and <dehydrate>. It’s nice to see the students connect what they already learned to what they are currently focusing on.

When I first saw the word sum for <pirate>, I had suspicions that this might not have an <-ate> suffix. But when I looked at the entry for it at Etymonline, I saw (as the students did) the related word <piracy>. So again, their hypothesis is based on thought and evidence. In looking at the word sum for <radiate>, I see a hypothesis in which the <i> is considered a connecting vowel. The entry at Etymonline does not support that. This word sum is one I will use to deepen their understanding of the information offered at this great site. Perhaps they are not familiar enough with Latin suffixes. Some will remember our investigation of <stratosphere> that led us to Latin stratus which became our Modern English base <strat> “layering, spreading out”, but many will benefit from having it pointed out again.

One last thing to point out on this list is the absence of the single final non-syllabic <e> on the suffix <-ive> in the word sum for <activate>. If I asked someone to spell <active> they would no doubt include it, but when they are looking at a word sum that includes more than one suffix, they often miss it. They are understanding the final <e> that is found on the end of many bases, but not that it is often found at the end of suffixes as well!

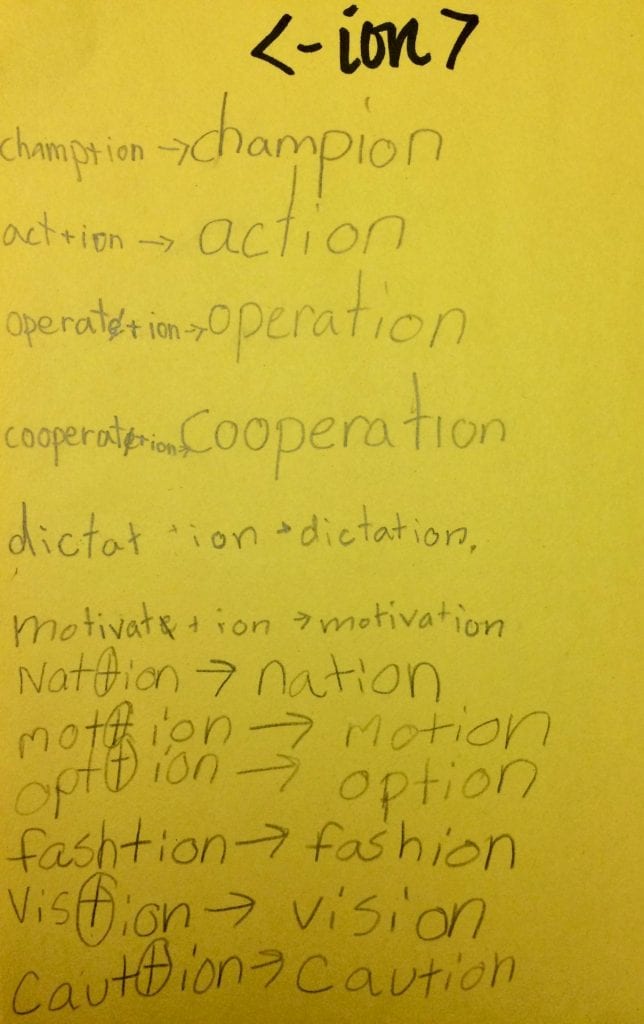

<-ion>

I can tell by looking at these sheets that the students are familiar with this suffix and recognize it as part of a word sum. Since they were so focused on proving the <-ion> suffix, some missed a second suffix in the word. One of these days I’ll write <operation> and <cooperation> on the board and ask for word sum hypotheses. I wonder how long it will take to spot the same base element in each. Hmmmm. I will also see if students see the two suffixes as <-ate> and <-ion>. Those two are often seen in combination. (See that last word? Ha! I proved my point!) I might even ask for the students to help me brainstorm a list of words that include both.

Next, I could do the same with <motion> and <motivation>. The first word has one suffix, but the second word has three. Perhaps I could have the students brainstorm a list of words with <mote> “move” as a base. Then I could ask questions such as, “Who can spot a word in this family that has three suffixes? Who can spot a word in this family that has a prefix? Who can spot a word in this family that has only one suffix? Will we ever see this base without a suffix or prefix?” You get the idea. Depending on the related words we thought of, I could keep going with questions to make sure everyone is engaged and thinking about what we are seeing. Of course we would follow up any answers given with: “Prove it by writing a word sum on the board next to the word.”

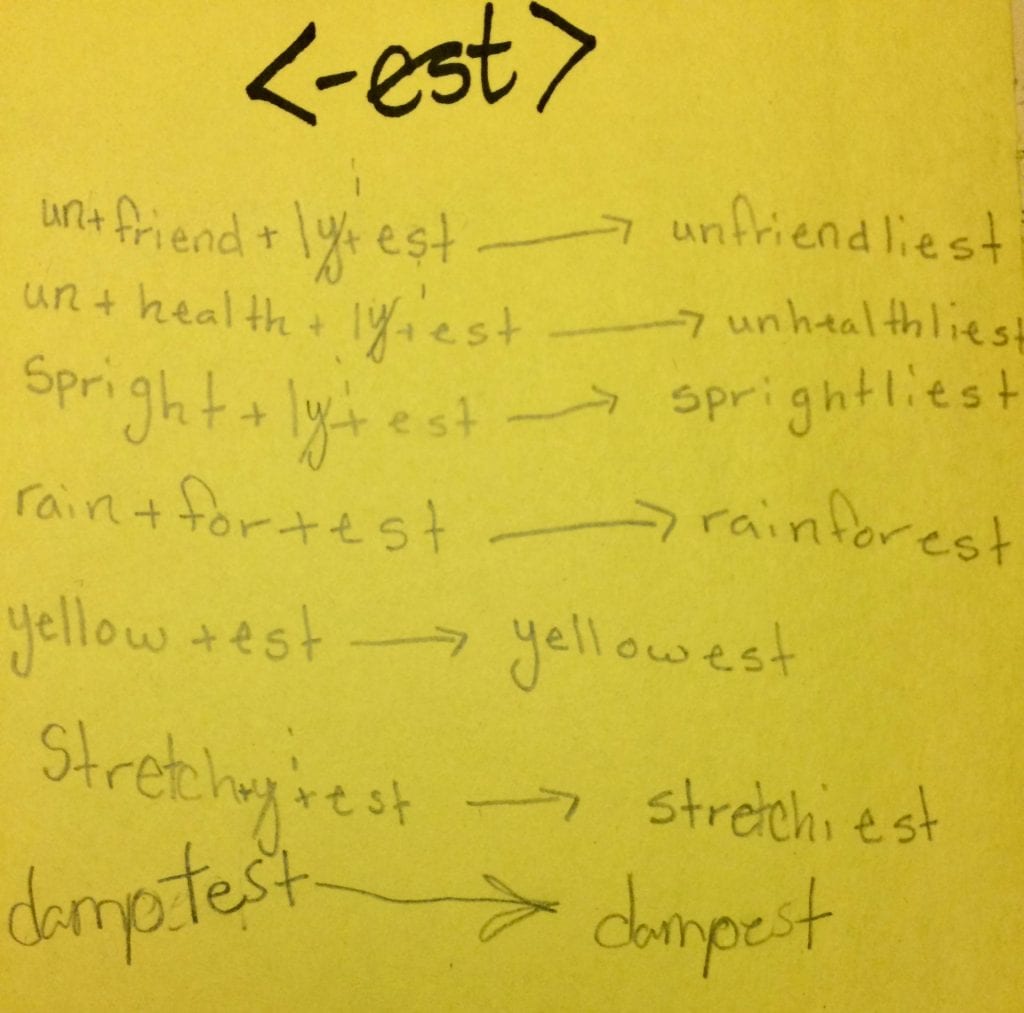

<-est>

I wonder how long it would take the students to identify which part of speech these words could be classified as. “Were they adjectives before we added this <-est> suffix?” This could turn into a great discussion of comparative and superlative adjectives! If I felt some of the students didn’t understand this idea, we could use the superlative adjectives on this list and write them in their comparative and adjective forms:

superlative comparative adjective

unfriendliest unfriendlier unfriendly

sprightliest sprightlier sprightly

yellowest yellower yellow

I bet you noticed the word sum for <rainforest>. Setting up the columns for comparative and superlative adjectives might help students recognize that this word is not like the others. And then a glance at Etymonline will provide evidence that the <est> is not a suffix in this word. It is just part of the spelling.

<-ist>

When I ask my students to write a word sum and the final graphemes represent /ɪst/, they often spell it as <ist>. Comparing the <-est> list to the <-ist> list might help them understand the difference between these two suffixes. Let’s take a look at the sheet of words with <-ist>.

I hope you are starting to catch on that each one of these lists is full of opportunities for discussion and deepening understandings. Look at the second word on this list <ageist>. Why aren’t we replacing that single final non-syllabic <e> on the base? Show them what it looks like when you do replace that <e> and see how the students pronounce it.

I’m not sure why there is an <o> in the word sum for <chemist>, but it might be interesting to put this word on the board and ask for related words. Then we could find the base and see how many different suffixes (besides <-ist>) are used with it.

As we read through this list, I might ask if these are adjectives like the list that had <-est> suffixes. Hopefully we’ll get to the realization that words with an <-ist> suffix often refer to a person. When they do, they are called agent suffixes. For example, the dentist is the person who takes care of problems with your teeth. A harpist is a person who plays the harp. We could do down the list, reading the word sums and identifying whether or not the word is referring to a person.

The word <copyist> is a great one to use when talking about an instance in which we do NOT switch the final <y> to an <i> before adding the suffix. The more I can have my students vocalizing the reasons they do and do not use suffixing conventions, the better.

I’m sure you’ve noticed the word sum for <hypnotherapist>. That looks like a great one for the board. “What is your hypothesis? Does anyone else have a hypothesis? If we removed the <-ist> suffix, what other suffix could we replace it with and still have a familiar word? Have you ever seen the beginning of this word in another word? How about the part right in front of the <-ist> suffix?”

On the other hand, the word sum for <climatologist> is pretty impressive. Our work with the base <log> is paying off. They are recognizing it in new words! The fact that this group left the <e> from the <-ate> suffix in the final spelling is something to note, but in the scheme of things I think that kind of error will correct itself with more application of the suffixing conventions and more reading aloud of word sums.

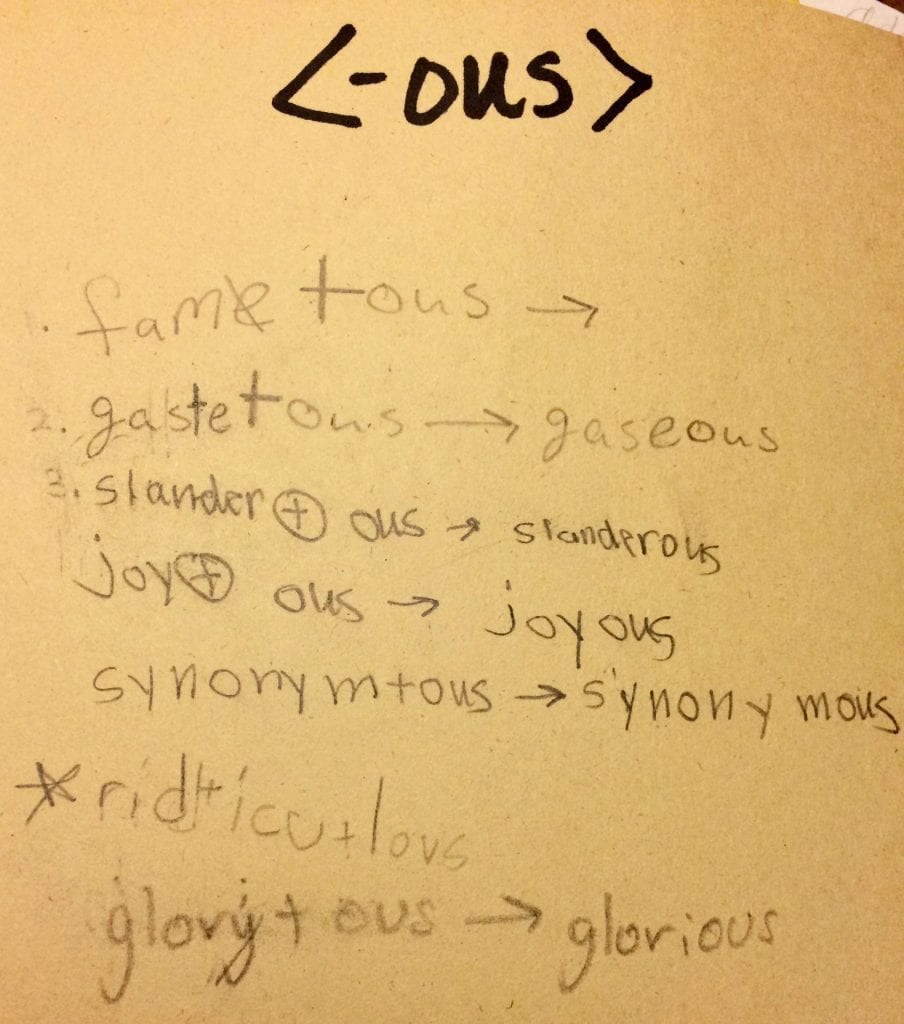

<-ous>

There are some really great things to notice about this first sheet. In the word sum for <gaseous>, there was the recognition that the <e> would have to be a connecting vowel! It clearly is not part of the suffix nor the recognizable free base element. There was also the recognition that if we remove the <-ous> suffix from <famous>, the single final non-syllabic <e> replaces the suffix. The free base would be <fame>.

The inclusion of <synonymous> is interesting. The changes in stress, and therefore pronunciation, brought on by adding or removing the suffix might make the recognition that <synonym> and <synonymous> are related words a tad difficult. It wouldn’t be the case for all students, but it would be the case for many. I will definitely want to bring this word to everyone’s attention. With some hypotheses offered, we could then investigate it further and find its relationship to antonym, homonym, anonymous, and pseudonym. I’m sure they will get a kick out of their respective senses: “opposite name”, “same name”, “not named”, and “false name.”

This sheet also gives us the opportunity to see what others think of the asterisk that was placed in front of the word sum for <ridiculous>. “If you agree that as written this word sum is questionable, what do you think the word sum is? What makes you say that?” Then we could go to Etymonline to find the evidence together.

One group working with this <-ous> suffix called me over to talk about the base having a final <y> that becomes an <i> in the final spelling. I showed them how to represent that change in the word sum. This is definitely something we will spend some time on in the next few weeks. Understanding the suffixing conventions takes care of so many misspellings. The students start feeling better about themselves as spellers without feeling like they worked hard at it. (Comparing the time they used to spend with rote memorization. For too many that felt like hard work with few results.)

Summing it up

These sheets provide all the example words I need! The activity was fun for the students, gave them valuable practice at using two trusted online resources, and revealed much to me about what kinds of practice they need next. I was able to see patterns that could be used to help the students understand a word’s use a bit better based on its suffix! These sheets can be used to inspire many many activities. I could simply post any of these on the board and ask for reactions. It would be a great way to stimulate question asking and reviewing important word structure features. I could ask any of the following:

Are there words you don’t know?

Do you see a word that could be further analyzed?

Do you see a word that you think doesn’t belong on the list?

Do you see a base identified here that you aren’t so sure of?

Is there a suffixing convention happening in any of the words on this list?

I know there are those who wish that SWI came with a scope and sequence, but really? Why set up a generic plan for generic children when we have real children right in front of us with specific needs! Their own work reveals what they need, and when the specific work is repeated at a later date, can reveal growth.

My first reaction to these sheets is one of optimism. They understand so much already. I always keep in mind that on day one of 5th grade, they believed that English spelling couldn’t be understood. They had no expectations that I would teach them anything different from that. But at this time of the year, they are starting to believe differently. They have experienced for themselves the evidence and reasoning. The rest of the year will be so much fun! They will become better at spelling, but they won’t remember having studied or memorized letter sequences in order to do it.