“Prejudice feels like a white-hot wire being pressed to your heart.

Even when the sting goes away, a mark is left there.” (M.F.)

“Prejudice feels like you are the broom

being pushed against the floor.” (K.M.)

“You are separated by an imaginary wall from everyone else.

You just keep losing over and over again.” (C.L.)

Such powerful images. Illustrating feelings of being uncomfortable and not at all in control. It might surprise you to learn that these feelings are being described by ten-year-old White children in a predominately White school in a small, predominately White village. How could they possibly understand what being on the receiving end of prejudice might feel like? How does anyone begin to understand an experience that has never been their own?

I credit Jane Elliot. She is one of many people have inspired me to try new things throughout my teaching career. Even though I never personally met Jane Elliot, I couldn’t shake the impact she had (continues to have) on both adults and children. I first heard of her in 1998 when we were showing a video to our fifth grade students entitled ABC News: Prejudice – Answering Children’s Questions. The video was hosted by Peter Jennings, and Jane Elliot was a guest on the show. As part of the show, Jane Elliot conducted an experiment. She gave green collars to all of the children who had blue eyes. Then she proceeded to treat them as if the color of their eyes indicated that they were not as smart, not as able, not as trustworthy, and not as patient as the children with brown eyes. It was something to watch.

After seeing how she conducted this experiment and how the students reacted, I was fascinated and wanted to learn more about her. I found this video and watched it. It is a documentary of the full experiment she implemented in her all White classroom in the late 1960’s. The very first time she conducted this experiment was the day after Martin Luther King, Jr. was assassinated. She knew that something had to be done so that her White students could understand what Black people were experiencing in our society. Over the years she has continued to use this same approach to illustrate what discrimination feels like to people of all ages and in a multitude of situations.

Watching the shorter segment on the Prejudice: Answering Children’s Questions video, we saw how angry the students became who were told to wear green collars. Some wore expressions of confusion and hurt. Others became belligerent, which only made things worse for them. It was powerful because it was quite obvious those children hadn’t ever experienced such unfairness based on something they couldn’t control (eye color). My students said they could understand what those with green collars must have been feeling based on the demeaning language and harsh condescending tones coming from Jane Elliot. But was simply watching it enough to leave a lasting impression? I didn’t think so. So I asked my students if they wanted to do this same experiment in our classroom. They didn’t hesitate. This was something they wanted to try.

Before we actually carried out this experiment, the students had an idea of the role I would play and what might occur with them. But still, we needed to have a heart to heart. I warned them that we would all need to take this very seriously. I would still be their teacher, Mrs. Steven, but there would be things I said and did that would surprise them. And not in a good way. I would need to play the part of a teacher who truly thought some of the students were “less special” than the others. The fact that they were still excited to do this and thought it would be fun, told me just how necessary it was. I hoped I could pull it off. I told the students to go home and discuss with their families what we would be doing based on what they saw in the video. There were about three parents who contacted me to let me know they were strongly in favor of this.

In preparation, I brainstormed several things I could do that children would think of as unfair. That wasn’t a difficult task. I decided that dividing them by eye color was probably the best. I happened to have some pink felt, so as the students came in the next day, I looked into their eyes and handed the blue-eyed children a piece of felt and a safety pin. That way it was more obvious to all which students had blue eyes, and which didn’t.

I knew my students had gym first thing, so I contacted the gym teacher the day before to ask if she would be willing to participate. She thought it was a great idea, and thought of her own ways to discriminate. As the students came in, she told the students wearing pink felt that they had to jump rope for a warm up and that they had better get going. The rest of the students were given a choice of running laps or jumping rope. It was the first of many times that morning that feelings would be hurt and things would not feel fair.

After gym, it was normal to let the students get a drink at the bubbler, and then walk back to class. However on that day only some were allowed to get a drink at the bubbler outside the gym. The students wearing pink felt had to use the bubbler in the first grade hallway. When they arrived back in the classroom, they were scolded for having taken too long.

I had some desks arranged in a circle and the rest in rows toward the back of the room. My tone was sharp and impatient with students wearing the pink felt, whereas it was smooth and friendly with the rest. When there were questions about the work, I answered the questions asked by the brown-eyed students first and was very thorough in my response. If that group had no questions, I answered the questions asked by the blue-eyed students, but hinted that they should have learned the information last year. I suggested they work harder and pay better attention in class.

The students noted later that our room had never worked so quietly. But it wasn’t a comfortable quiet. The morning subjects were interrupted by one 15 minute recess, and the students came back grumbling about having had a rotten time. When it was time for lunch, I joked with some and sent them off with a smile. With others, I implied they were holding up the line and to hurry! When they returned from lunch and recess, they were visibly upset. Their emotions were so stoked that the littlest look or the smallest criticism was crushing. They hated this day and this experiment. It hadn’t been fun for anyone, including me. But did it hit its intended target? We would see.

I told them that the experiment was officially over and that those with the piece of pink felt could now remove it. There were cheers signaling relief. As I was collecting the felt pieces, I had everyone put their desks back into the normal arrangement and then get out a piece of paper. I told them how important it was for them to write down what they were thinking and feeling while it was still fresh in their minds. What follows is a sampling of those responses.

Today freaked me out. It was scary. So what if I have blue eyes. I heard tons of comments Mrs. Steven made about us and saw the things she did. I would almost be the saddest person on earth if this happened to me every day. This whole day I have been writing things down on my desk about what happened. For one, there were two milk counts. Eli, a “bluey,” had to go get the milk for his group in a cardboard box, and Sam got to use the regular milk crate for the rest of the students. The “blueys” even had to use the third grade bathroom which is all the way down the hall, when the fifth grade bathroom is right outside our door!

During science, she only let the “brownies” read aloud from the book. When she handed back papers, the people with blue eyes had to get up and get their papers while people with brown eyes got to stay seated and Mrs. Steven handed their papers to them. When we called the other students “brownies,” Mrs. Steven said, “Don’t call names!” When we said, “But they were calling us blueys.” She said, “Well, you are.”

I hated it soooooooooooooooooooooooooooooooo much. I was treated so badly. I wanted to go home all day. I was wishing I had brown eyes. I felt like getting my stuff and walking home. I felt like almost hurting someone. I felt mad at some of my friends. I felt alone and stupid. I felt like if someone shot and killed me, nobody would care. It was a horrible/awful/hateful experience.

I felt like I was very special compared to the blue eyed people.

I wanted to tell her not to treat us like that just because we’re different. She wouldn’t let us go to the bathroom or get a drink of water. When Mrs. Steven did that to us, I felt like nothing … like a piece of dust in the wind … or an atom, because I was so tiny.

I liked it because Mrs. Steven trusted the “brownies.” I hated it because at lunch recess I was playing four square, and some people that were “blueys” said I couldn’t play because I had brown eyes. That right there cut me real deep. I don’t know if they were joking or serious. Either way it cut. I didn’t like how my friends separated from me.

The blue-eyed people asked for help on math, but all she said was, “You’re smart kids, aren’t you?” It would hurt my feelings if she said that to me. It hurt my feelings, and she didn’t say it to me.

Today Mrs. Steven was being prejudiced. Even though I wasn’t hurt by her words, I could tell other people were. I care about my friends, so that’s why I got mad when she was being mean to them.”

This was the worst day ever. It was awful. I didn’t know Mrs. Steven could be such a pain. She acted so serious. The only reason muddy eyed people got to go first at everything and get treated better is because Mrs. Steven doesn’t want to be second class. She wants to be “Little Miss Perfect.” Man, Mrs. Steven must really love being born with muddy eyes. I hope she is not offended, but I feel like I could punch her.

Prejudice is awful. It’s a problem. I liked it at first, but then it got serious. All this fighting about something stupid. My friends hating me. Me hating them. At one recess no one would play with me except the other “brownies.” I didn’t have any fun. When we came in, some of us were calling the other kids names. It got so out of hand.

This experiment began at roughly 8:15 am and ended at 12:45 pm. I stopped it when I did so that we would have the afternoon to reflect and process. What you’ve just read is really something, isn’t it? This half day experiment had a big impact. Some were hurt and took the pain inward. They felt defeated and wished they weren’t born with blue eyes. Others were angry at the unfairness. Some of that anger was directed at other children, and some of it was directed at me. You could sense that the anger was bubbling, and if this had continued much longer it might have turned into something physical. Those were some of the reactions to those with blue eyes, anyway. The reactions of the brown-eyed children were different. Some were angry, yes. They saw the unfairness and felt bad for the blue-eyed children, but they didn’t cross the line I had drawn. They didn’t get as angry and didn’t reach out to those for whom they felt sorry. In a very real sense, both groups displayed a kind of powerlessness regarding the situation. At any rate, I’m glad the feelings were real and that they were strong enough to become embedded in their memory.

Let me clearly state that even with their “powerful” feelings, I think these children had only an inkling of an understanding about prejudice and discrimination. How could it be more than that when they have not experienced it in the real world day after day after day? But an inkling may be enough for them to develop an empathy for people who do experience these things. It may be enough for these children to remember that everyone isn’t always treated equally in our society.

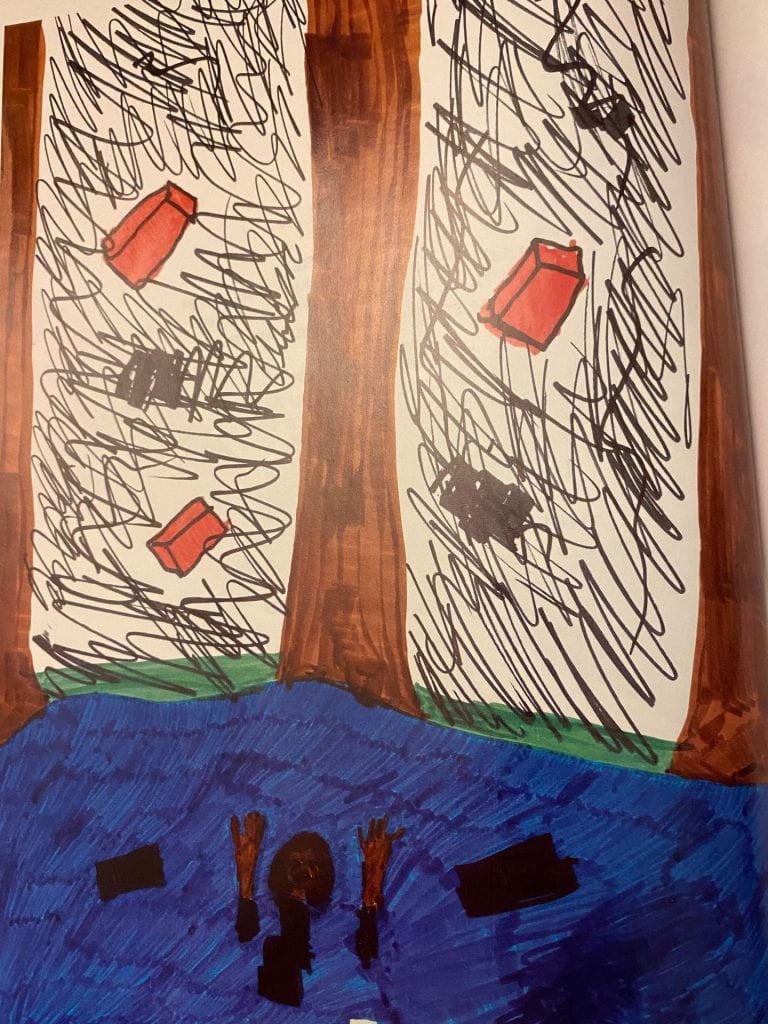

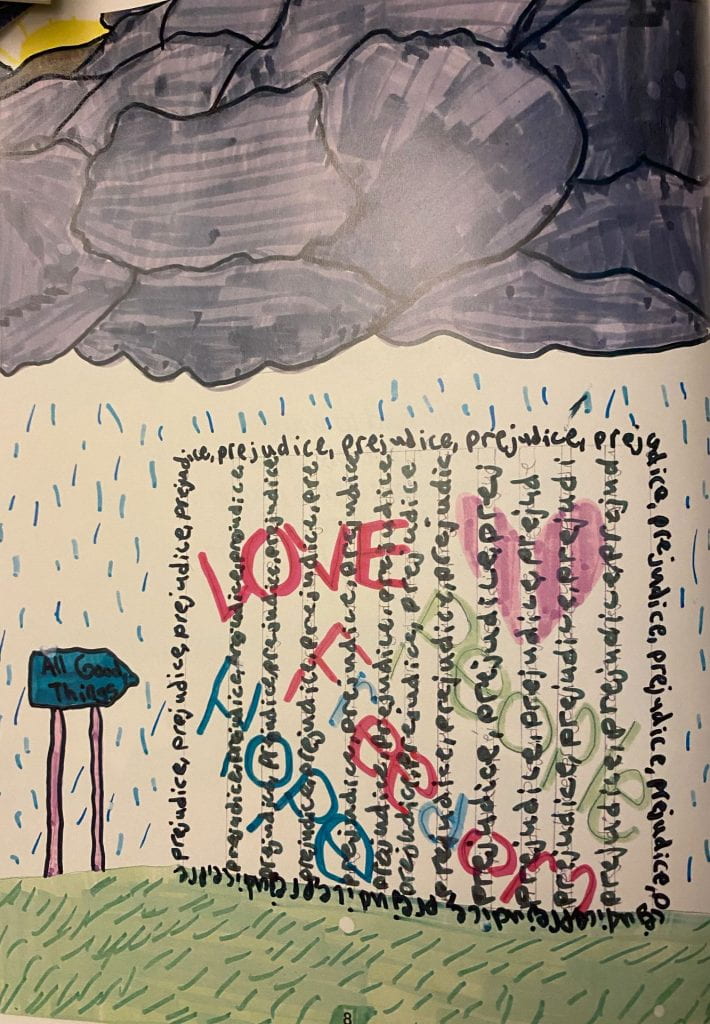

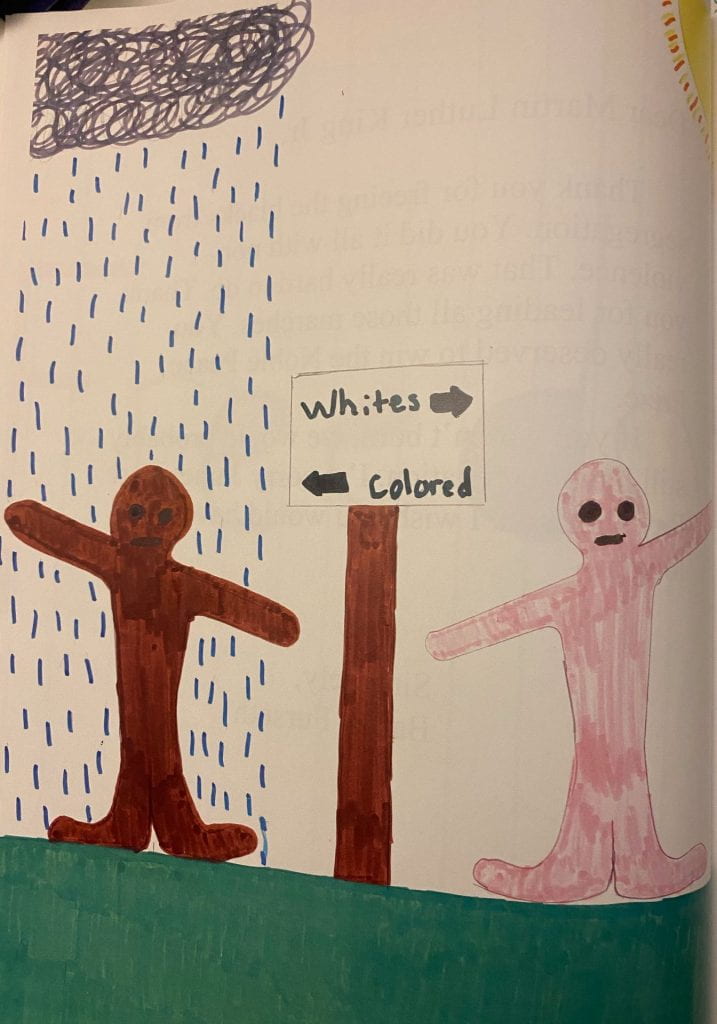

After the initial writing was finished and people said what they wanted to say about the experiment, I handed out big 12 x 18 inch pieces of construction paper and colored chalk. We spaced out our desks so that each person had a bit of privacy. It was to be a quiet time to explore feelings about prejudice and discrimination. I told them I wasn’t looking for recognizable images, but rather for them to choose a color to begin with and to let how they were feeling be the thing that moved that piece of chalk on the paper. They could change chalk colors as they wanted. After I felt students had had enough time to express what they maybe hadn’t yet put into words, I had them wash their desk, their hands, and then stand in a large circle with the desks displaying their drawings in the middle. I made it very clear that no one would be asked to defend or explain their drawing. We were going to look at the drawings and see what we noticed.

One of the things that stood out was that several drawings were full of dark colors that were kind of scribbled reminding us of a tornado or a knotted ball of string. Others had sharp angled lines or zigzags with marks that looked like tears falling. There were squares within squares drawn that were dark and smudged on the inside. These did not evoke feelings of happiness or cheeriness. More often the words offered by the students were trapped, confused, angry, sad, hurt, helpless, and furious. Now contrast those drawings with the few that had suns drawn on them and included lots of flowy bright colors. Happy, fearless, content.

The drawings were a meaningful way to share what other people were feeling without those people having to say a thing. And yet the drawings themselves speak loudly about what prejudice and discrimination do to the members of a society. The children with brown eyes felt bad momentarily for the other children, but in the end their own life was still represented by sunshine and cheery colors. They saw, they recognized the difference, but felt it wasn’t something they could change. There was at least one or two who drew images that evoked conflicted feelings. One side of the paper would have a light fluffy kind of feel, but the other would have an image that became swirled into a colorful mess. It wasn’t dark or smudgy or angry feeling like some of the images drawn by the blue-eyed children, but there was a feeling of unrest.

Can you see how these feelings reflect some of the real life tensions we see in our world today? Those who are on the receiving end of prejudice and discrimination don’t all react to it in the same way. Some push and question the authority of those whose actions are discriminatory. Some are overwhelmed with feelings of anger and frustration at how unjust the system is, and they physically, sometimes violently, react to it. Some become withdrawn, powerless, and lose self-worth. And what about those watching the discrimination and prejudice? Some speak up about the unfairness, but many like being first and the privilege that comes with “having brown eyes.” They tend to look at things as fine the way they are, even though they wouldn’t want to trade places with the group being discriminated against.

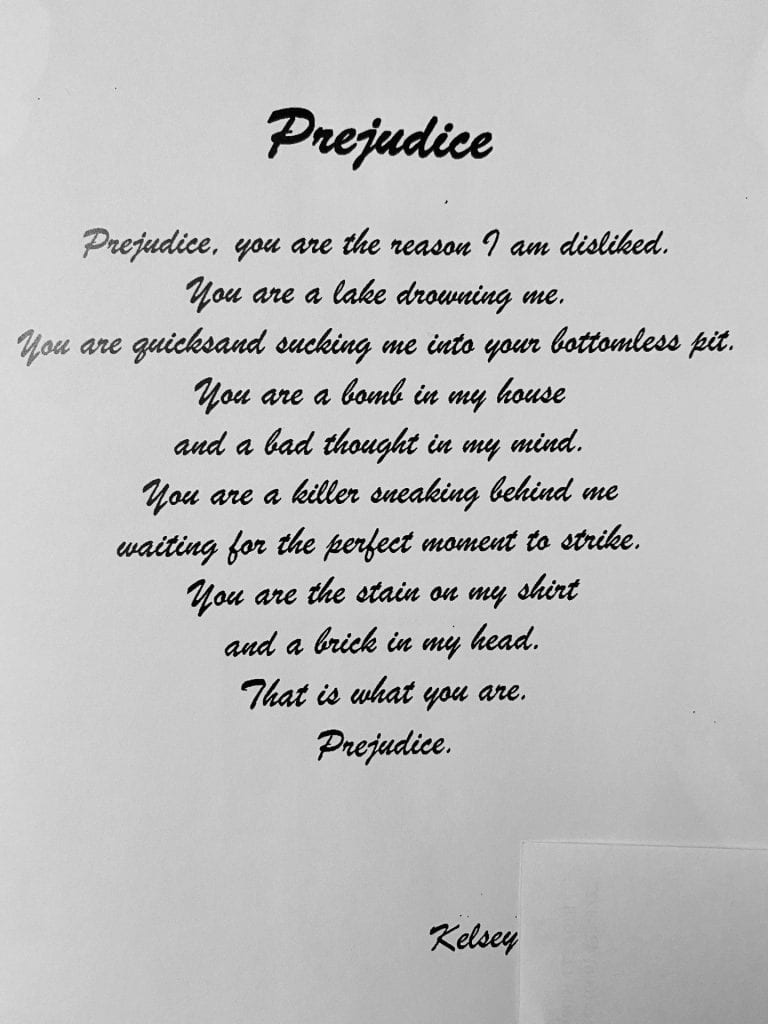

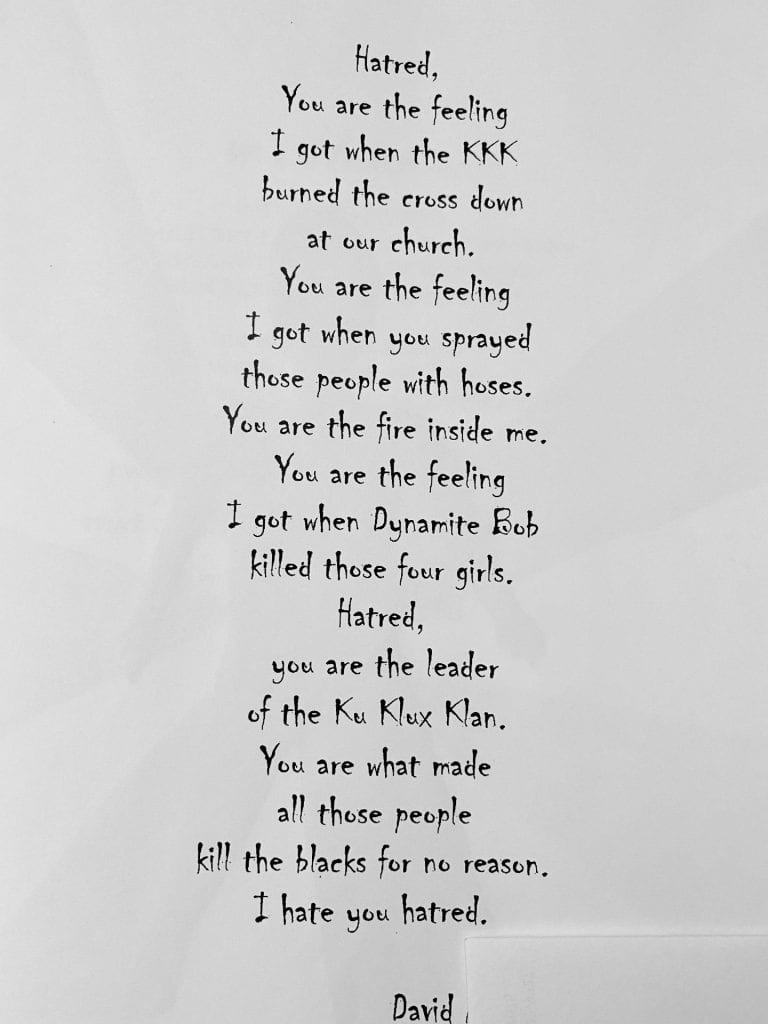

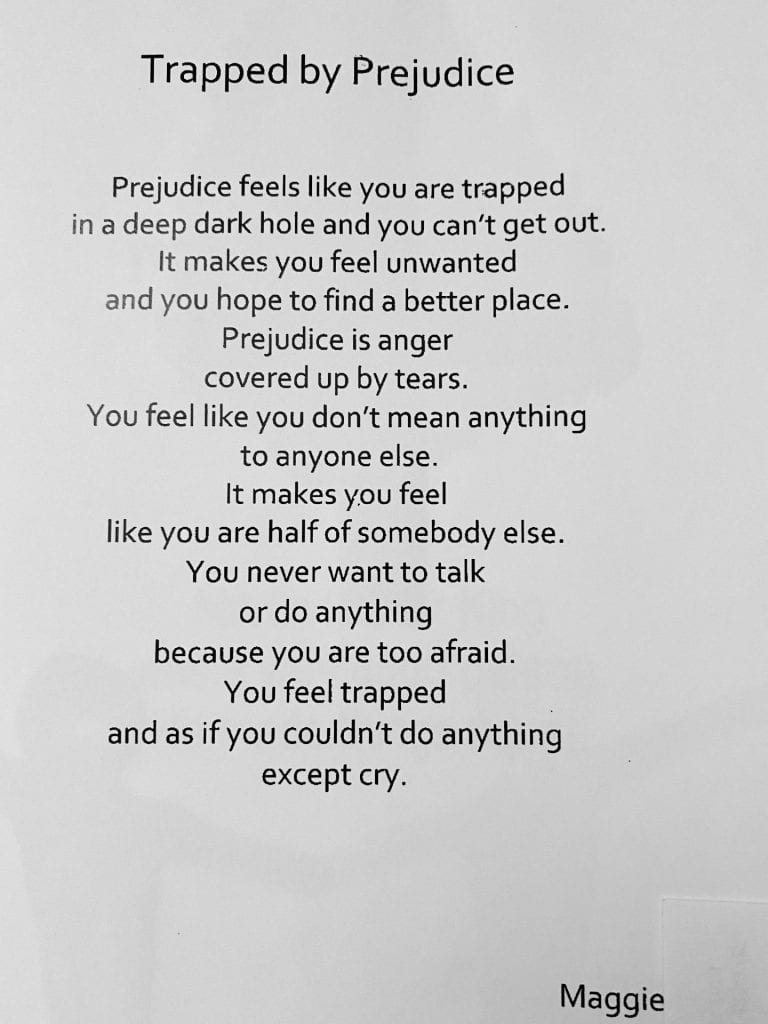

The last part of the day was spent writing poetry. I asked them to try to put into words what they saw in their drawings. What follows is a sampling of those poems which were formatted and finished the next day.

Prejudice really stinks.

All the anger builds up and up.

I hate it.

It’s like a rainstorm on a party,

a bomb exploding in my head.

It’s odious.

I want to run away from it. (J.B.)

Laughing was not allowed

Eyes made us different

From everybody else

Today.

Out of the way, the brownies say

U are not the best

Today. (E.G.)

Prejudice is

like I’m a squirrel trapped in a cage with bears,

like I have no power,

like everyone is an eye, and I am blind,

like I’m a rabbit in a wolf family,

like I’m being blamed for something I didn’t do. (D.P.)

Prejudice feels like getting trapped under

a dock in the middle of the sea.

It’s like the devil pulling you to the core of the earth. (K.S.)

Prejudice is like you’re in a glass cage trying to get out.

It’s like walking up an escalator that goes down. (N J.)

Prejudice makes you feel like a rain drop in a pit of flames,

like there’s a dark wall, or maybe a giant not wanting to move out of your way.

Don’t people know? It’s what’s inside that counts. (A.H.)

Prejudice is a storm, screaming and yelling,

laughing, not with me, but at me. (L.S.)

Prejudice feels like someone keeps hitting you

until you just fall down in pain.

It feels like the rage of a storm over only your head.

Prejudice feels like walking through a jungle of people

determined to make you feel hurt. (G.L.)

To me prejudice felt like no one cared about me.

It made me feel all alone. It’s hard to describe with words.

I felt hatred, anger, sadness, and confusion.

I wanted to scream. (M.M.)

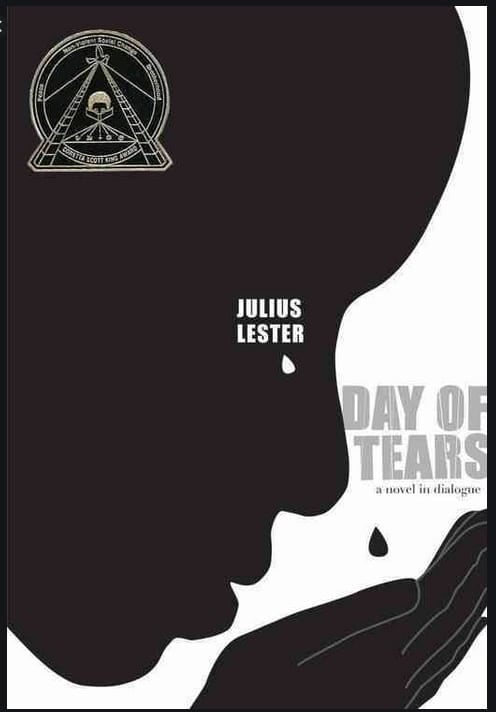

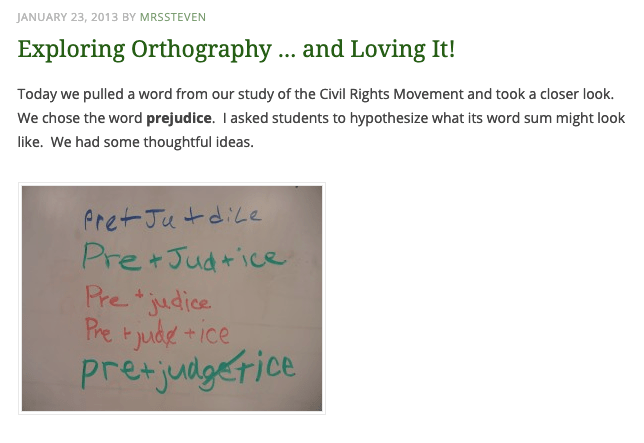

I have many many more poems in my collection. Because from 1999 until 2014, I repeated this experiment with every new group of fifth grade students. We usually did it in January while we were reading Martin Luther King, Jr.’s biography. That was when we were encountering those words, so it made sense to do it then. Later on, in March and April, we applied this deeper understanding of what Black people have been up against in our country when we were studying the American Civil War. We stepped away from the textbook and each were responsible for several researched reports that when pieced together gave us a broad picture of how the War affected people from all walks of life at that time. One of my preferred read-alouds during this study was Day of Tears by Julius Lester. It is a story of the largest auction of slaves in American history. Over 400 slaves were sold in two days. I felt as if my students were better equipped now to imagine what it would be like in someone else’s shoes.

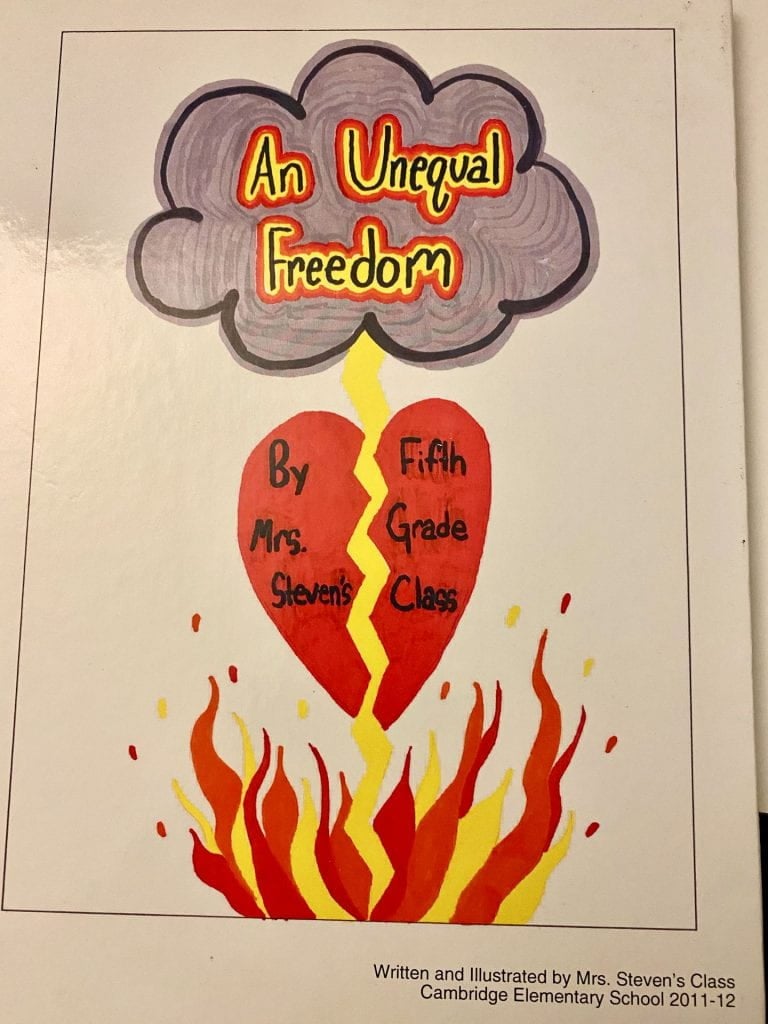

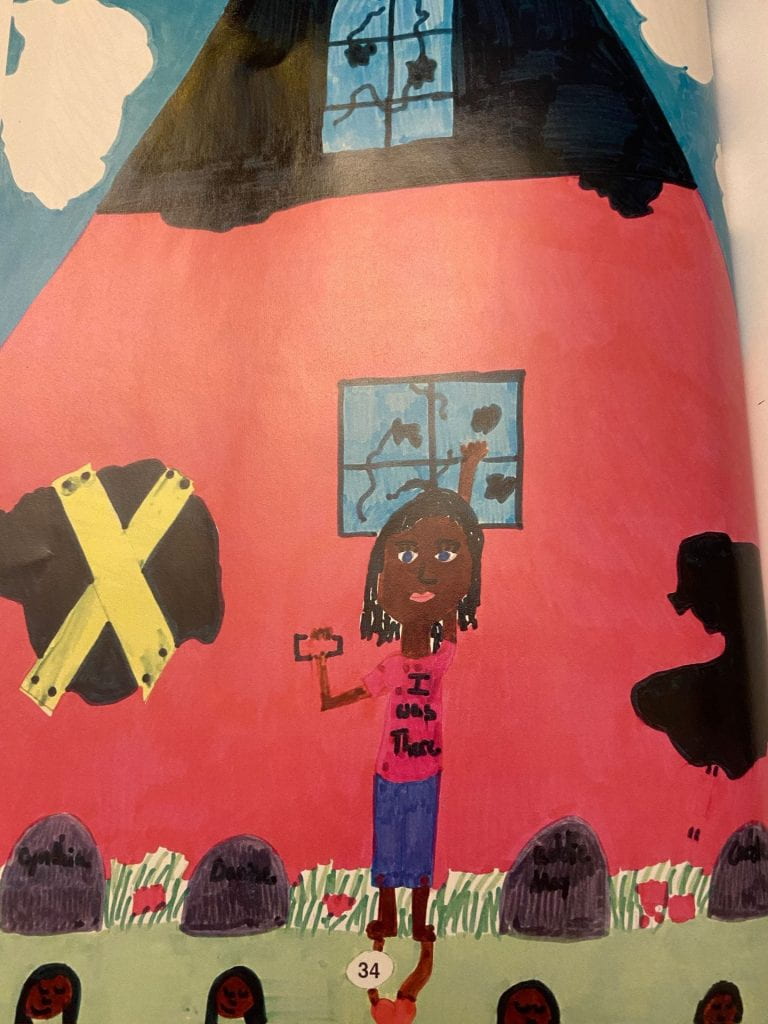

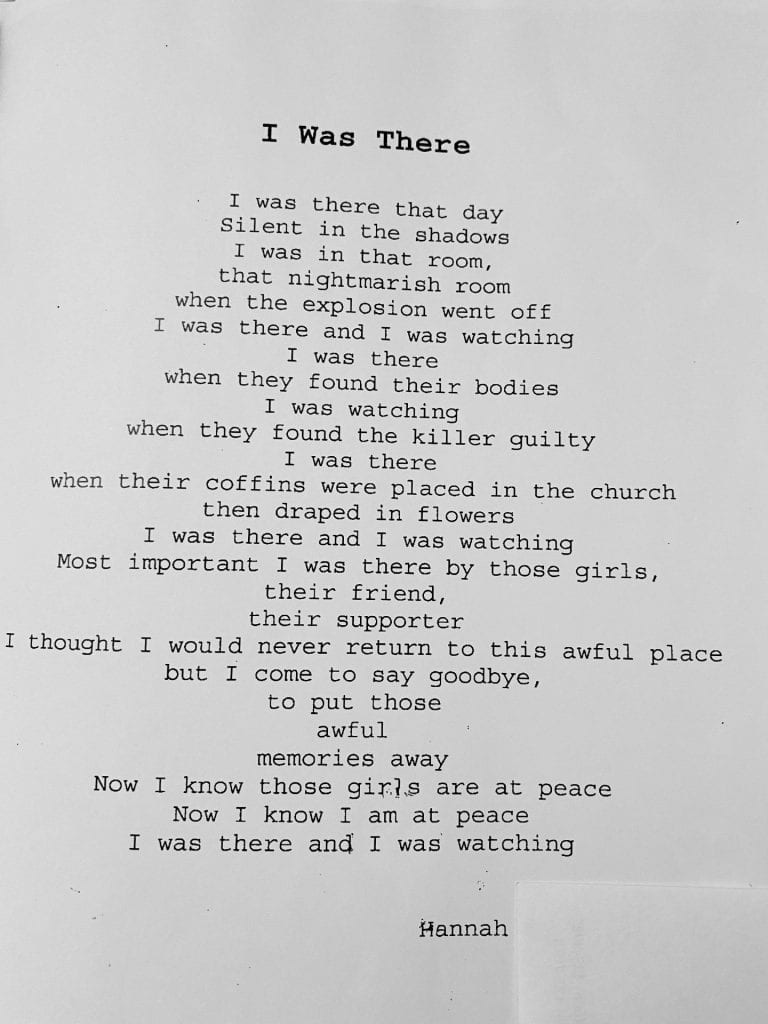

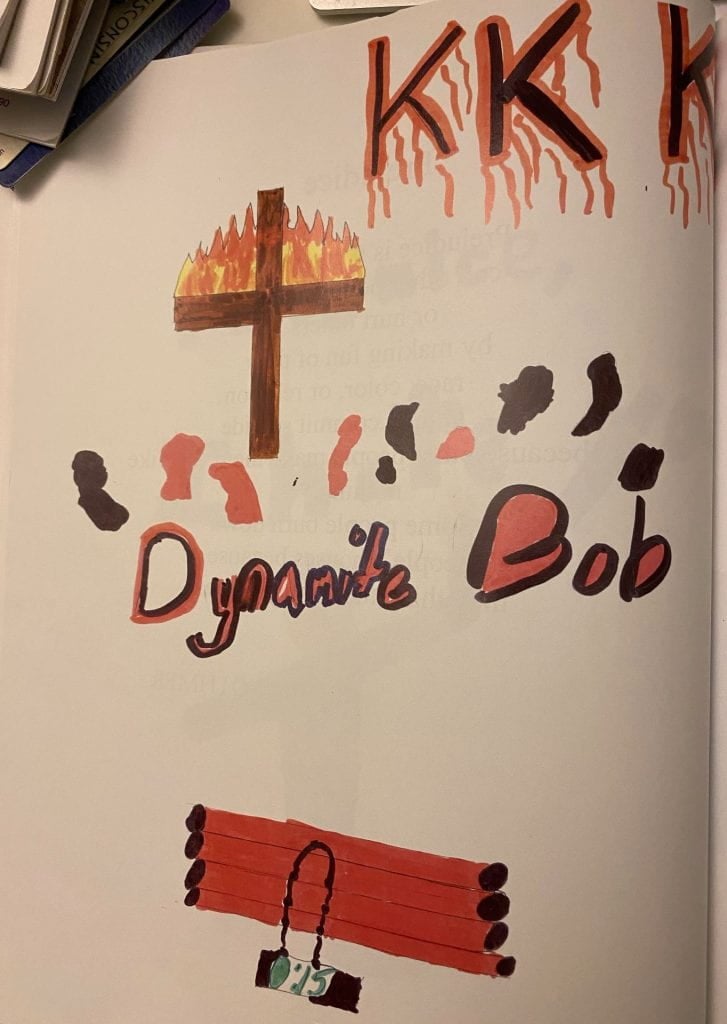

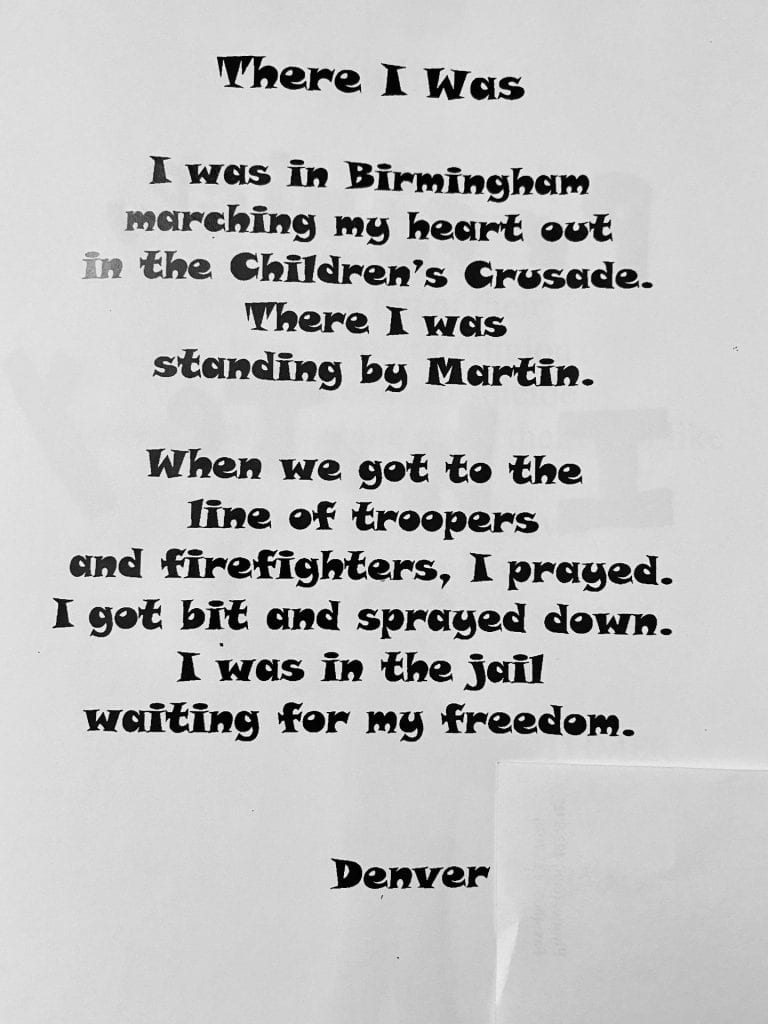

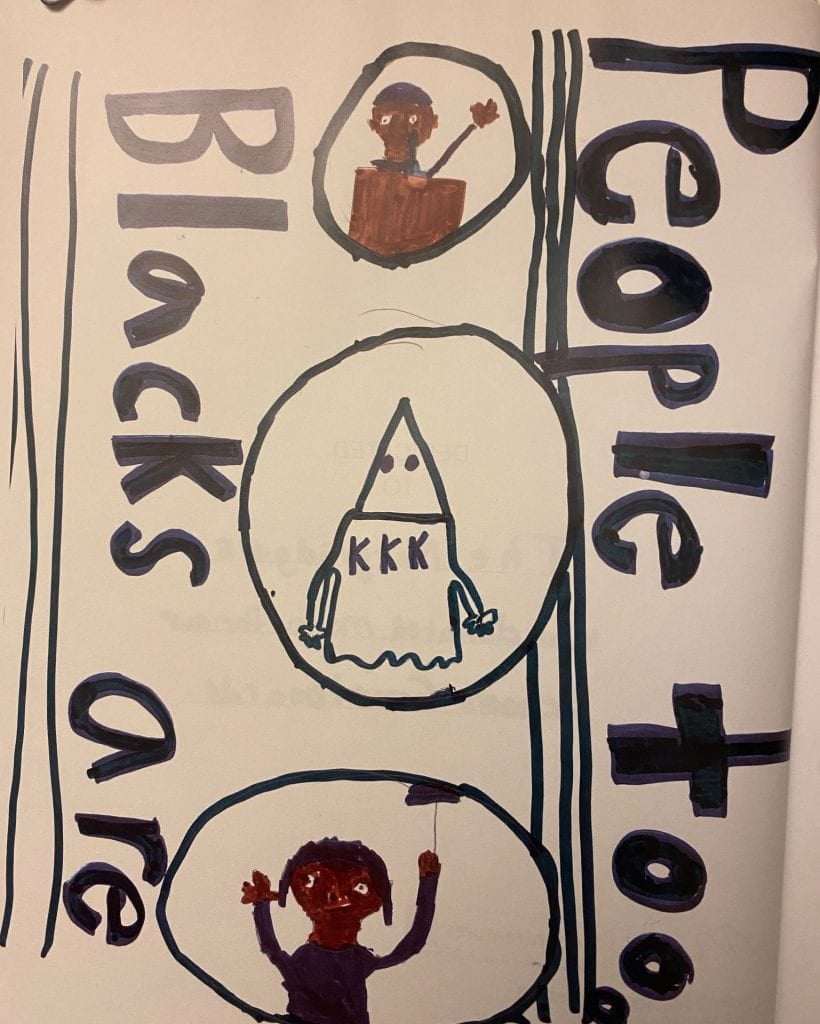

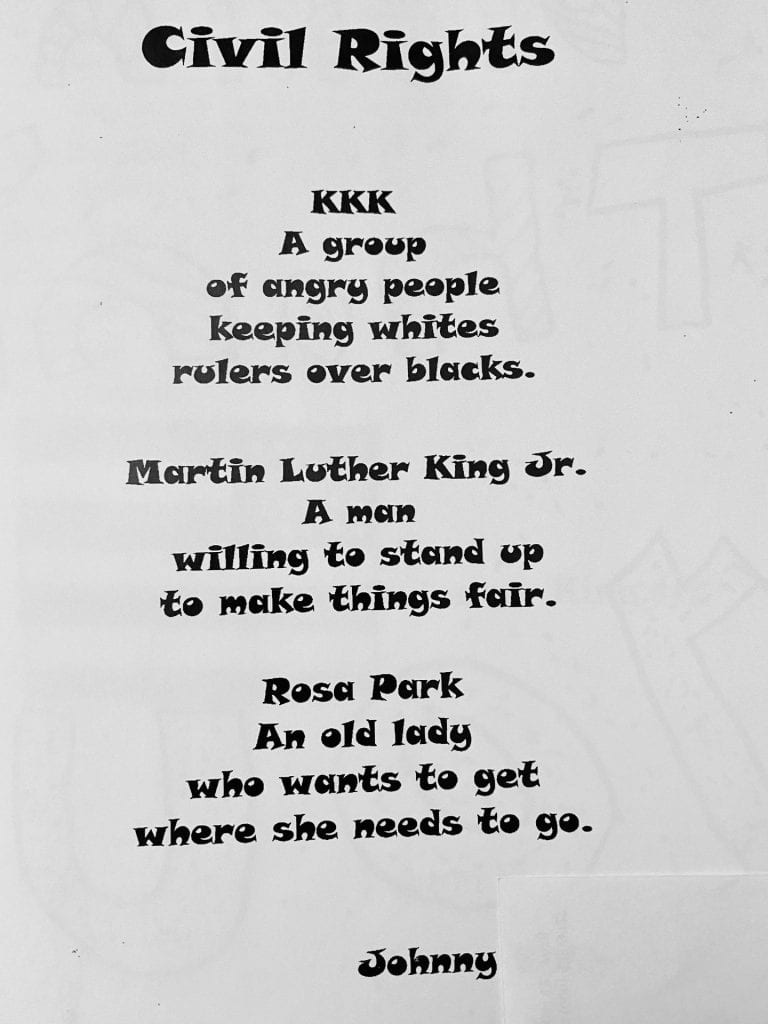

Many times we also wrote poems to reflect on our study of the Civil Rights Movement as a whole. Some wrote letters to Martin Luther King, Jr. instead. In 2012, we published a book of our poems called An Unequal Freedom. Each student (and the teacher) contributed a poem and a drawing. The students named the book and they each submitted art for the cover that we later selected by a vote.

Here are some samples from our book.

Even though this was an uncomfortable kind of experiment, I am glad I saw Jane Elliot when I did. I’ve been reminded of her recently. Because of the racial unrest in our country, she has been interviewed and many of her videos have resurfaced. If you haven’t heard of her, I suggest you read this NPR article about Jane Elliot, or search for her on Youtube and watch some of the other videos of her in action. Over the years she has continued to use this same approach to illustrate what discrimination feels like to people of all ages and in many situations. Every time I watch her in action I am reminded that it is the experience that helps you “get it.”

Every once in a while I will run into a former student who will mention that this experiment is something that has left a lasting impression. Below is a recent comment I received from just such a student.

“One lesson I will never forget was when our all White class was learning about the Civil Rights Movement, our all White class that lived in an all White community, and you divided us up by eye color to teach us about racial prejudice. It was a lesson for a lifetime. I remember that day so clearly, and I was in the 5th grade!”

As much as I love that comment, what I love even more is that this student was in my fifth grade classroom in 1999! That is 21 years ago! Talk about a classroom activity having a lasting impression! But did it change the way those children thought about Black people? I know it did at the time, but how many of my former students took this understanding into their adult lives? I think it is pretty obvious that the effectiveness of this experiment isn’t the kind of thing I can measure properly. So many experiences contribute to the shaping of who we are at any given moment. And I have no way of knowing what other experiences those students have had that may have either strengthened or weakened what they learned that day. But I believe it was important to do. Many students have mentioned it over the years as we have talked and reminisced. Much like the student I’ve quoted above, they didn’t really feel the full impact of it until they were adults navigating jobs and social situations in the real world. And I believe that it provided a glimpse of something they wouldn’t experience and understand in any other way.

“When you judge another, you do not define them, you define yourself.” Wayne Dyer