It is a hard-to-believe concept, but it’s true. Words do not have the spellings they have so that we know how to pronounce them. Words like busy, does, piano, action, and pretty prove that. The truth is that words are spelled the way they are to represent their meaning. That’s such a foreign idea to so many. “If that was true, wouldn’t we teach that to children who are just learning to read?” You’d think so, wouldn’t you? But the majority of schools don’t. So why do we resist believing this obvious truth?

When I first began studying orthography and learning Structured Word Inquiry, I was skeptical myself. I wondered what people in this community meant when they said that spelling represented meaning and not pronunciation. How can that be? I learned to spell by “sounding words out” – by pronouncing them. Sometimes I pronounced them in unnatural ways so that I could remember the spelling (Wed – nes – day or ap – pear – ance, both with parts pronounced unlike they are in the whole). I knew what the words meant, but that didn’t have anything to do with the spelling, did it? I learned to spell one word at a time, twenty or so words a week. I was pretty good at rote memorization. I also studied definitions right out of the dictionary. They didn’t always make sense to me, but because they didn’t, I didn’t know how to reword them. I found out when my children went to school that times haven’t changed much in this regard.

I remember when my son was in high school and had to be able to match up a list of words to their definitions. I offered to help him study. That was when I realized that he had figured out a system to pass the test without having learned anything useful. If I read the word, he could give me the first four words of the definition. If I read the definition, he could tell me the first four letters of the word the definition would match up with on the test. Blech! He became very annoyed with me when I pointed out how useless this test was. “Mom! It doesn’t matter. I have to pass the test tomorrow. Go away. I’ll study by myself.”

One thing is for sure. He was smart enough to know that passing the test didn’t hinge on him actually understanding anything. I was sad, but remembered cheating my own learning in the same way as I went through schooling years. I didn’t cheat my learning to the extent my son did, but cheat it I did. Neither of us were taught to look to the word for meaning – we had learned that spelling and meaning were two separate activities and rote memorization was the only way to handle them in order to pass the test.

Recently Oxford Dictionaries posted the ten most frequently misspelled words in their Oxford English Corpus (which they describe as “an electronic collection of over 2 billion words of real English that help us see how people are using the language and also shows us the mistakes that are most often made”) . Seeing as I spend a fair amount of my teaching life looking at misspelled words, I took a look, wondering if I could predict the words that made the list. As I was clicking, my mind was betting that the people who misspell these words (whichever they were), had an education like mine and have been taught to “sound out words” and not to even consider morphology or etymology as they relate to a word’s spelling.

Here is their list:

*accomodate (accommodate)

*wich (which)

*recieve (receive)

*untill (until)

*occured (occurred)

*seperate (separate)

*goverment (government)

*definately (definitely)

*pharoah (pharaoh)

*publically (publicly)

Once you begin to study orthography and use Structured Word Inquiry, it doesn’t take long to see how easily the above spelling errors could be avoided altogether. The people misspelling these words do not understand the spelling – have not been taught to understand the spelling. Let’s look closer at each of these. Along the way I’ll point out the information that would actually help a person understand and remember these spellings.

accommodate (*accomodate)

meaning:

Before we talk about spelling, it’s always important to talk about how the word is used. What does it mean? I could talk about the fact that my classroom can accommodate 30 students, meaning that the space is adequate to fit that many students. I could also use it if I was talking about accommodating the needs of a student who has a broken leg. In that sense, I am fitting the needs of the student by perhaps getting a different type of desk.

morphology:

A person without any understanding of morphology might be wondering, “Is it two <c>’s and one <m>, or is it one <c> and two <m>’s?” That person might even write the word down on a piece of paper with several different spellings to see which one looks right.

Here’s what you understand when you understand morphology. All words have structure. That structure will include a base element and perhaps affixes. A base element will either be free (doesn’t HAVE to have an affix) or bound (MUST have an affix).

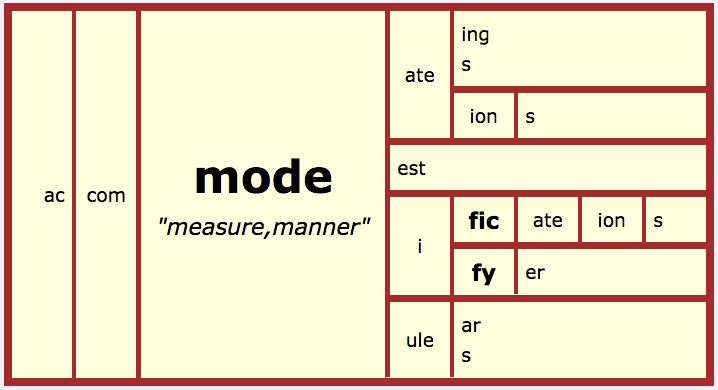

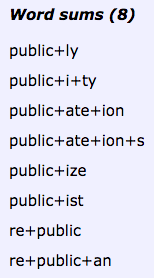

Let’s look at the structure of <accommodate>. This word consists of four morphemes: two are prefixes, one is a base, and one is a suffix. Its structure is <ac + com + mode/ + ate>.

The first prefix is <ac->, and it is an assimilated form of the prefix <ad-> “to”. When a prefix is assimilated, it means that the final letter in the prefix might change to better fit phonologically with the first grapheme of the next morpheme in the word. In this case, the original form of the prefix is <ad-> “to”. Seeing as the next morpheme begins with a <c>, the <ad-> assimilated to <ac-> to better match the phonology of that <c>.

The second prefix is <com->, and it is an intensifying prefix. That means that it brings a sense of force or emphasis to this word. There are people who have learned this prefix and will tell you that it means “together”. Well, it does bring that sense to some words we find it in. But there are prefixes that can also be intensifiers, such as this one!

etymology:

The base element of this word is <mode>. It is a free base element from Latin modus “measure, manner”. This base can also be found in words like:

modify, modular, accommodation, model, modest, and yes, even commode!

The suffix is <-ate>. It is a verbal suffix.

Let’s put the morphemes together and understand this spelling: <ac + com + mode/ +ate –> accommodate>. If you stop yourself from thinking of there being a double <c> and instead think of the prefix <ac> plus the prefix <com> plus the base <mode (replace the <e>)> plus <ate>, you will have spelled this word with very little problem. At the same time, you will understand that the denotation of this word is “to fit with emphasis”. Compare that denotation with a connotation (how the word is used now), and you will have the spelling AND the meaning, and understand both!

phonology:

It is important to recognize that pronunciations are affected by many things. I will include a generally accepted pronunciation for each of these words. But please know that there may be pronunciation variations in different parts of the country / world. The pronunciation is /əˈkɑməˌdeɪt/. Here is the phoneme / grapheme correspondence:

<accommodate>

/əˈkɑməˌdeɪt/

It is interesting to note that the first <o>, which is stressed, has a different pronunciation than the second <o>, which is unstressed.

which (*wich)

meaning:

We often use the word ‘which’ when we are searching for more information about one or more things or people in a specific group. One might ask, “Which book is yours?”

morphology:

This word is a free base. It has no affixes.

etymology:

To understand the spelling of this word, we need to look at its etymology. I have several sources I use when researching words. One of my favorites is Etymonline, but I also have copies of Chambers Dictionary of Etymology and John Ayto’s Dictionary of Word Origins.

This word is Old English in origin. According to Etymonline, it was spelled both hwilc (West Saxon, Anglian)and hwælc (Northumbrian). (Notice that the <hw> is now <wh>). It is short for hwi-lic “of what form”. It is interesting to note that in early Middle English there were two other forms (hwelch and hwülch). They later lost their <l> and became hwech and hwüch. Both of those spellings disappeared in late Middle English.

When you understand that the <h> has always been part of this word, and that in fact, it used to be the first letter, it is easier to remember that it is STILL part of this word. It is pretty obvious that those who misspelled this word used phonology alone. But its spelling takes us back to Old English and the important evidence that the <h> has always been part of this word.

phonology:

The pronunciation is /wɪtʃ/. Here is the phoneme / grapheme correspondence:

<which>

/wɪtʃ/

receive (*recieve)

meaning:

This word generally means to be given, presented with or be paid for something. I receive a pay check. I have received several awards. I received help from my neighbor.

Now I’m willing to bet you are already thinking, “i before e except after c … blah, blah, blah”. I came across an article by The Washington Post recently. To read it, CLICK HERE. It seems a statistician named Nathan Cunningham plugged a list of 350,000 English words into a statistical program to check out this age old rule. He found that in words with a ‘ie’ or ‘ei’ sequence, <i> came before the <e> almost 75% of the time. So then he checked for the “except after ‘c’ part”. He found that in words with a ‘cie’ or ‘cei’ sequence, ‘cei’ occurred only 25% of the time. That leaves 75% of that group of words to be exceptions! So much for that rule! Yup! The rule with lots and lots of exceptions. And as any good researcher will tell you, if your rule has a lot of exceptions, you need a new rule!

Besides wasting time memorizing a rule that you can’t count on statistically, there is another reason to abandon the “i before e” rule. It simply doesn’t take into consideration what else is important about a word – like its morphology and its etymology! Let’s get out of the land of ‘hit and miss’ and look at this word seriously.

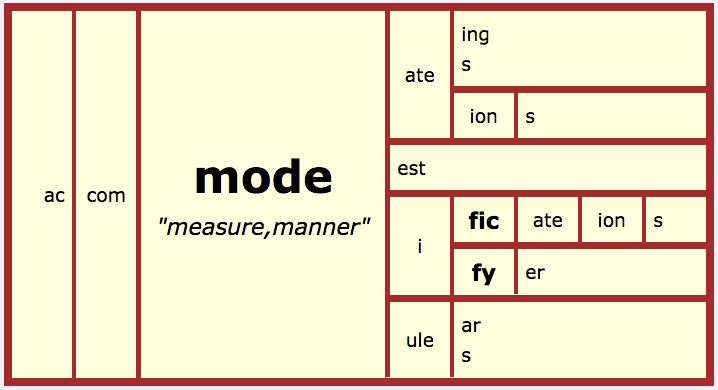

morphology:

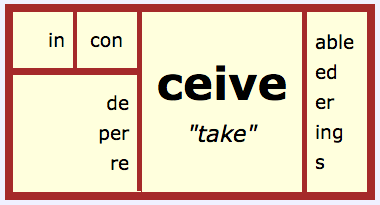

Based on other words I have investigated, I might make a hypothesis about this word’s structure like this: <re + ceive –> receive>. I know that in words such as recall, reclaim, and refill, <re> is a prefix. It could be a prefix in this word too, although I need specific evidence pertaining to this word to be sure. I need to look at where this word comes from – its etymology.

etymology:

This word has come into English by way of Old North French receivre. Further back, it is from Latin recipere (re– “back” + cipere, combining form of capere “to take”). Looking back in time, this word has had a meaning and sense of “regain, recover, take in, admit”. When I look closer at the Latin verbs capere and its combining form cipere, I find other words that share this base <ceive>:

~perceive (<per-> has a sense of “thoroughly”, thus when you perceive something, you are thoroughly taking it in in order to comprehend it),

~deceive (<de-> has a sense of “from”, thus when someone deceives you, they take from you – they cheat you),

~conceive (<con-> is an intensifying prefix, meaning it gives emphasis to the base, thus when someone conceives either an idea or a baby, they are taking something in and holding it)

~transceiver (which is a relatively new word – 1938, created by combining transmitter and receiver).

So what we learn from this word’s history is that its spelling has been fairly consistent since the 1300’s. No gimmicky rhymes needed.

phonology:

The pronunciation is /ɹəˈsɪv/. Here are the phoneme / grapheme correspondences:

<receive>

/ɹəˈsɪv/

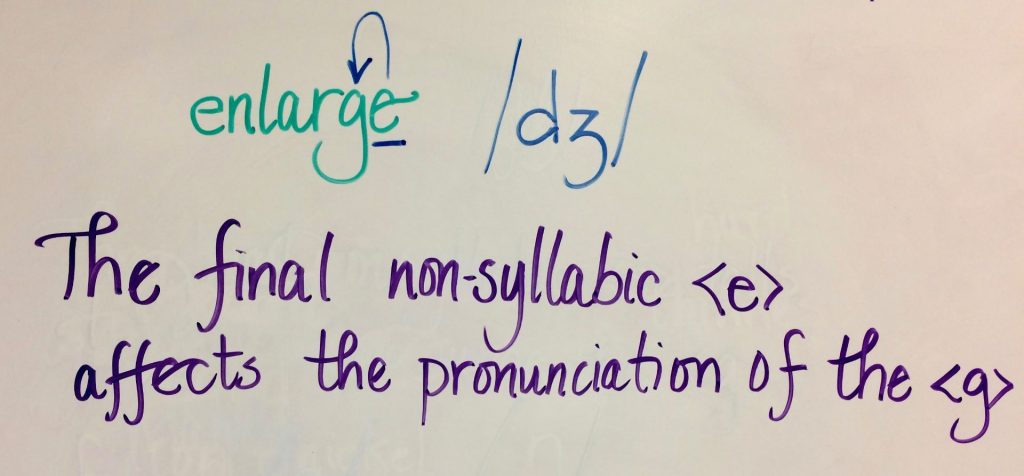

It is interesting to note that the final <e> is non-syllabic and is preventing this word from ending in a <v> (no complete English word ends in a <v>).

until (*untill)

meaning:

This word means “up to (either an event or a point in time)”. If you say, “I will wait until you call,” it is functioning as a subordinating conjunction. If you say, “We swam until 5:00,” it is functioning as a preposition.

morphology:

This word is a free base in Modern English. It has no affixes. It might be tempting to identify the <un> as a prefix, but all you have to do is compare the etymology of the <un> in this word to that of the <un-> in words like unhappy and unzip. They do not share ancestors, nor do they share denotations.

etymology:

This word, as most, has an interesting story. The verb ’till’ meaning “to cultivate the soil” was first attested in the 13th century. It is from Old English tilian “cultivate, tend, work at”. There is a thought that the idea of cultivating and having a purpose and goal may have passed into Old English with the word ’till’ meaning “fixed point”. It was then converted into a preposition meaning “up to a particular point”. ‘Until’ was first attested in the 13th century. The first element <un> is from Old Norse *und “as far as, up to”. (The asterisk next to the Old Norse spelling means it is reconstructed.) So when we put the two parts of this word together, we get <un + til –> until> “up to a particular point”. The use of ’til’ is short for ‘until’.

It isn’t about “one ‘l’ or two”. It’s about the word’s story.

phonology:

The pronunciation is /ənˈtɪl/. Here is the phoneme / grapheme correspondence:

<until>

/ənˈtɪl/

occurred (*occured)

meaning:

If something has occurred, it has happened. It could be an event or even a thought.

morphology:

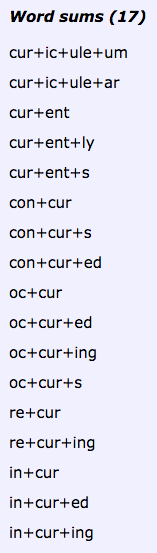

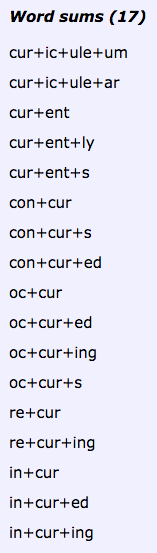

Someone who is misspelling this word, doesn’t understand its morphology. That would include how suffixing conventions are applied. The structure of this word is <oc + cur + ed –> occurred>. Notice that the final <r> on the base was forced to double when the vowel suffix <-ed> was added. This happened because of the position of the stress in this word. The stress is on the second syllable – the one closest to the suffix.

etymology:

This word was borrowed from Latin occurrere “run towards, run to meet”. The prefix <oc-> is an assimilated form of the prefix <ob-> bringing a sense of “towards”. The base is <cur> “run “. This base is seen in present day words including curriculum, current, recur and concur.

phonology:

This word is pronounced /əˈkɜɹd/. Here are the phoneme / grapheme correspondences:

<occurred>

/əˈkɜɹd/

It is interesting to note that the initial <o> is unstressed and that affects its pronunciation.

separate (*seperate)

meaning:

This word generally means to divide or cause to be apart. I might separate old coins from new coins.

morphology:

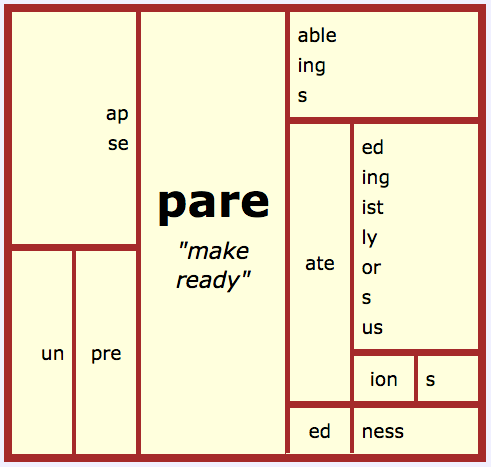

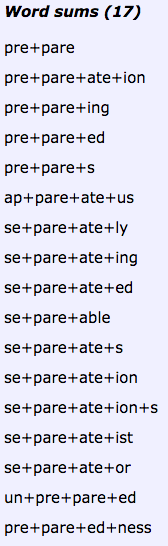

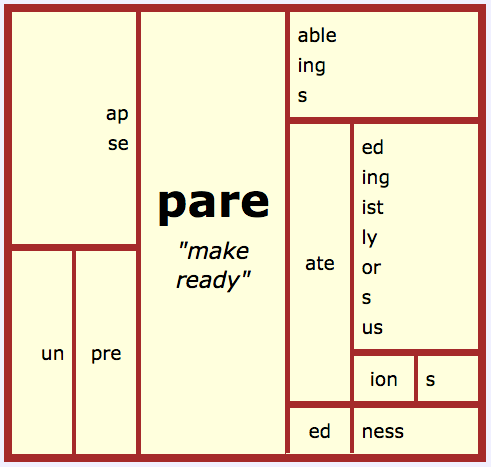

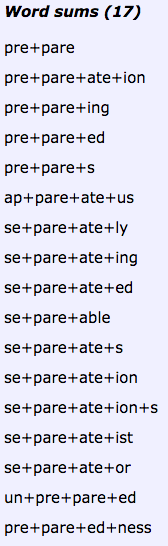

Growing up I remember this word being one that I could never get right. The reason I misspelled it time after time is because all I had was its pronunciation to work with. Had I known its morphology and etymology, I would have had a better chance of remembering its spelling. First, let’s look at its morphology. The structure of this word is <se + pare/ + ate –> separate>.

etymology:

The prefix <se-> has a sense of “apart”. The base element <pare> is from Latin parare with a denotation of “make ready, prepare”. The suffix <-ate> is a verbal suffix in this word. The base element in this word, <pare>, is also seen in words like:

~apparatus (The prefix <ap-> is an assimilated form of the prefix <ad-> and brings a sense of “to”. Apparatus helps to make things ready or be prepared.)

~preparation (The prefix <pre-> brings a sense of “before”. When you prepare, you make things read before you need them.)

~pare (This is a free base that means to “trim or cut close”. Again we see the denotation of “make ready” in the image of this word’s action.

phonology:

The pronunciation is /ˈsɛpɹət/. Here is the phoneme / grapheme correspondence:

<separate>

/ˈsɛpɹət /

It is interesting to note that the <a> is not typically pronounced in this word. The final <e>, which is the final letter in the <ate> suffix, is non-syllabic. That means it is not pronounced either.

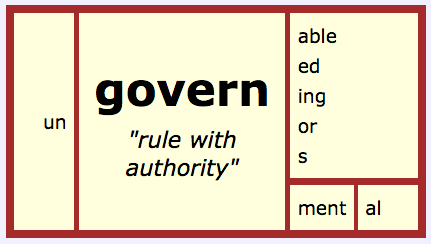

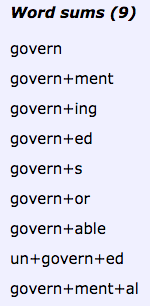

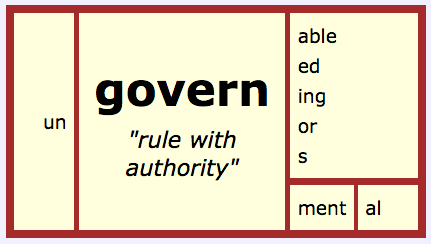

government (*goverment)

meaning:

A government is a way to regulate or control members or citizens of a particular region (state or country) or of an organization. In the United States, we have a federal government with different branches that creates laws for the entire country, and we also have state governments making decisions for each of the fifty states.

morphology:

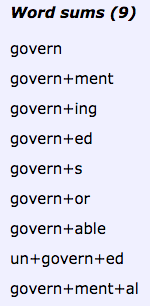

Why does this word get misspelled? Again, it is because of the way it is pronounced. So let’s look at this word’s morphology and phonology as we have with every other word so far. The structure of this word is <govern + ment –> government>. People who leave out the <n> in this word, don’t think about the word’s structure. The base shares its spelling with all words in its word family. See the matrix below.

etymology:

The base element <govern> was first attested in the late 13th century, and at that time it meant “rule with authority”. It is from Old French governer which meant “steer, be at the helm of, rule, command”.

phonology:

The pronunciation is /ˈgʌvəɹmənt/. Here is the phoneme / grapheme correspondence:

<government>

/ˈgʌvəɹmənt/

It is interesting to note that the <n> is not typically pronounced. This is evidence that it is important to have knowledge of a word’s morphology and etymology when trying to understand its spelling!

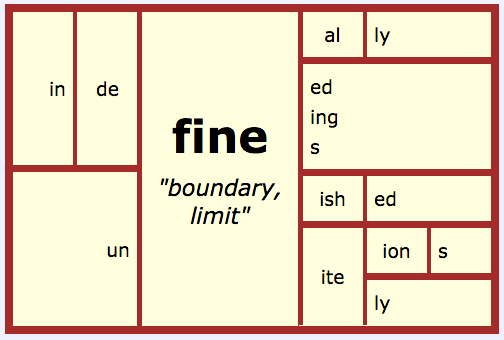

definitely (*definately)

meaning:

When used, this word is intended to remove all doubt. I will definitely watch your dog this weekend.

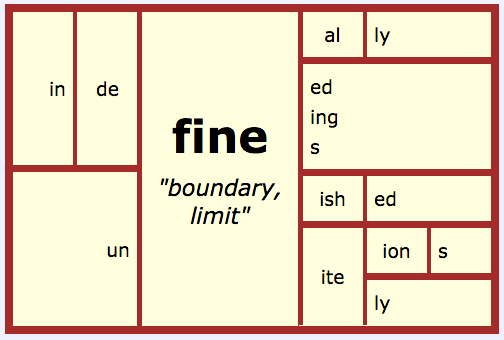

morphology:

The structure of this word is <de + fine/ + ite + ly –> definitely>. The single final non-syllabic <e> is replaced by the <-ite> suffix in the final spelling. The suffix <ite> is adjectival, but the addition of the suffix <ly> makes this word adverbial.

etymology:

This word is from Old French definir, defenir “to finish, conclude, come to an end, determine with precision”. Before that it came directly from Latin definire “to limit, determine, explain”. The prefix <de-> brings a sense of “completely” and the base <fine> has a denotation of “to bound, limit”.

phonology:

This word is pronounced /ˈdɛfənətli/. Here are the phoneme / grapheme correspondences:

<definitely>

/ˈdɛfənətli/

It is interesting to note that both <i>’s are unstressed which affects their pronunciation. The final <e> on the suffix <-ite> is predictably unpronounced. The final <y> on the <ly> suffix also has a predictable pronunciation.

pharaoh (*pharoah)

meaning:

A pharaoh is an ancient Egyptian ruler.

morphology:

This is a free base with no affixes.

etymology:

This word has an interesting trail to follow. It was first attested in Old English as Pharon. Earlier it was from Latin Pharaonem. Earlier yet it was from Greek Pharao. Even earlier it was from Hebrew Par’oh. But its origins are in understandably Egyptian Pero’ where it meant “great house”. Note that the spelling sequence of ‘pharao’ was present in Greek and in Latin. That is the spelling sequence we currently see. Once again the spelling represents where the word came from and what it means, not how it is pronounced!

phonology:

This word is pronounced /ˈfɛɹoʊ/. Here are the phoneme / grapheme correspondences:

<pharaoh>

/ˈfɛɹoʊ/

It is interesting to note that the <ph> represents /f/. This is a signal that this word has a Greek heritage.

publicly (*publically)

meaning:

When something is done publicly, it is done for all to see.

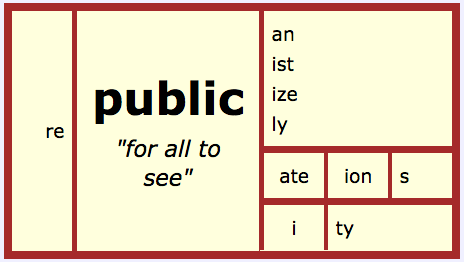

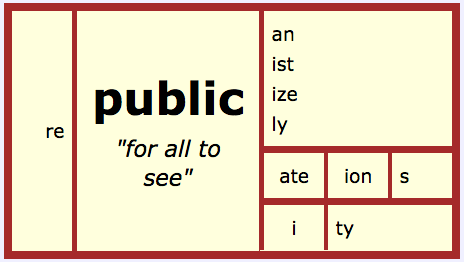

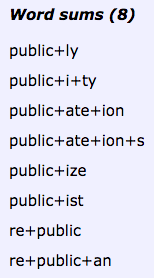

morphology:

The structure of this word is simply <public + ly>. The <ly> suffix can be an adverbial one. The misspelling listed shows a misidentification of structure. There are many words that actually HAVE that structure, including basically, magically, comically, and tropically. This brings us to an important point! Just because two things are pronounced the same, it doesn’t mean they are spelled the same. It doesn’t take much time or effort to check with a reference book!

etymology:

The word ‘public’ was first attested in the last 14th century. Earlier it was used in Old French public. It comes directly from Latin publicus “of the people, of the state, common, general”. The meaning of “open to all in the community” is from 1540’s English.

phonology:

This word is pronounced /ˈpʌblɪkli/. Here are the phoneme / grapheme correspondences:

<publicly>

/ˈpʌblɪkli/

It is interesting to note the predictable pronunciation of the final <y> of the <-ly> suffix.

Reflection

Think about the words on this misspelled list. Everyone of them has a spelling that can be explained by looking at the word’s morphology, etymology , and its phonology. I’ll say it again … by looking at the word’s morphology, etymology, and its phonology. Teaching all three is so powerful.

It’s time for schools to change the way they teach children about words and spelling! Phonology is just ONE ASPECT of a word. When it is seen as THE ONLY THING (as it is in most every classroom), students are cheated out of the opportunity to understand a word’s story. And understanding a word’s story is often the thing that connects a word’s meaning to its spelling. Understanding a word’s meaning leads to understanding the word in context, which in turn increases reading comprehension. How could it not?

Teaching spelling and reading via phonology alone makes spelling a giant guessing game. For example, there are a number of graphemes that can represent the phoneme /iː/. I can think of <ea>, <ee>, <y>, and <ei> off hand. There are no doubt more. A student faced with memorizing which grapheme to use in which word based on pronunciation alone is clueless – literally! That student NEEDS the clues that morphology and etymology provide. Why not teach a student where to find the information needed in order to make informed decisions about a word’s spelling?

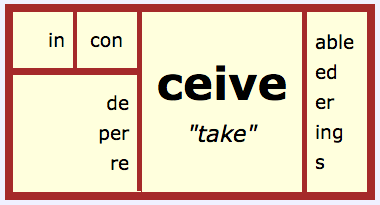

Another huge disadvantage of teaching as if spelling represented only pronunciation is that our students never see for themselves how words are connected to one another. They miss realizing that each word is a member of a larger family. The family is full of words that all share a common base with a common ancestry and a common denotation. Why are words like busy, business, and businesses found on different spelling lists? Why not present them together so a student can see they are part of the same word family? Or present them together so the students can internalize an understanding of the suffixing conventions that can happen within a family of words. The matrices I have created above do just that. They help us see connections among words that we have not been taught to see before now.

Let’s go back to the list of commonly misspelled words. Oxford Dictionaries only gave us their top ten, but I’m willing to bet there are hundreds and hundreds of such words in their Oxford English Corpus. I say, let’s raise the bar for our students. Let’s give them engaging word work that supplies them with resources for all the clues they need in order to understand a word’s spelling. What schools have been teaching students during reading and spelling instruction — phonology alone — has not worked for the vast majority of students. If it had, we would not see the spelling errors we do. We would not hear adults blaming the English language when they misspell a word or misunderstand a paragraph. We would not hear parents claim, “I was a terrible speller too” at parent-teacher conferences, as if not having been taught to understand our language is a trait one inherits much like height or hair color.