When thinking of a timeline between the introduction of words and their structure, and the final assessment of them, I’m in no hurry. Here’s how a recent review of a list of science words we have been talking about for a while went. A few months ago students were sent off in pairs to investigate ten words. After hypothesizing the structure of the word, their task was to figure out what the base was. As the groups began to dig in at Etymonline, I circulated to help them understand what to look for, and how to know if they found its earliest ancestor from which our modern day base is derived.

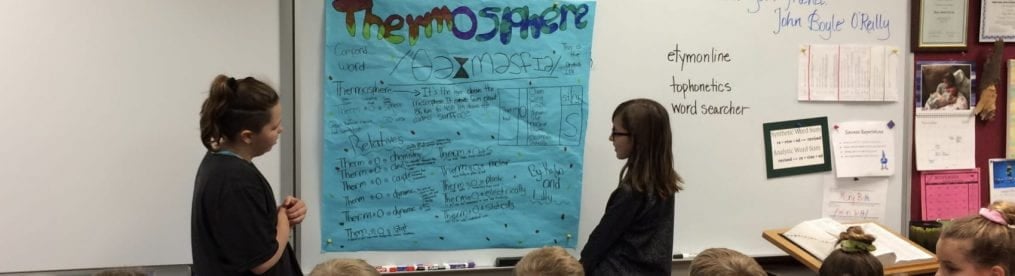

Each group of two made a large poster which was shared with the whole class before being posted in the hallway. We took our time in sharing those posters. We never presented more than two in one day. The students would hang their poster on the white board at the front of the room. All other students were asked to bring their chairs up front. I wanted them close, and I wanted them to participate in the sharing of each poster. I tell the “audience” that if we are to have learning that is worth anything, they need to participate. They need to listen carefully and to ask questions when something doesn’t make sense. They need to be thinking about other words that are not listed on the poster but just might be related.

In my experience, the research each student does and the information collected does not necessarily lead to long term understanding. The presenting of the information also does not necessarily lead to long term understanding. Instead it is the interaction with the rest of the class. It is the off the cuff discussions. It is the unplanned questioning. It is the words suggested as belonging to the base’s family and the reasons given. This kind of participation happening over and over leads to students who make contributions to the class that really do help all of us understand in a wider way. It doesn’t take long before the students realize that comments like, “I like how neatly you wrote on your poster” pale in comparison to “How did you know that the <o> was a connecting vowel in the word biosphere?” Yes. Their beginning of the year observations and comments are really that shallow and surfacey. It is quite different by the end of the year. Something is happening. They are noticing things that matter, and they are not remaining quiet about it.

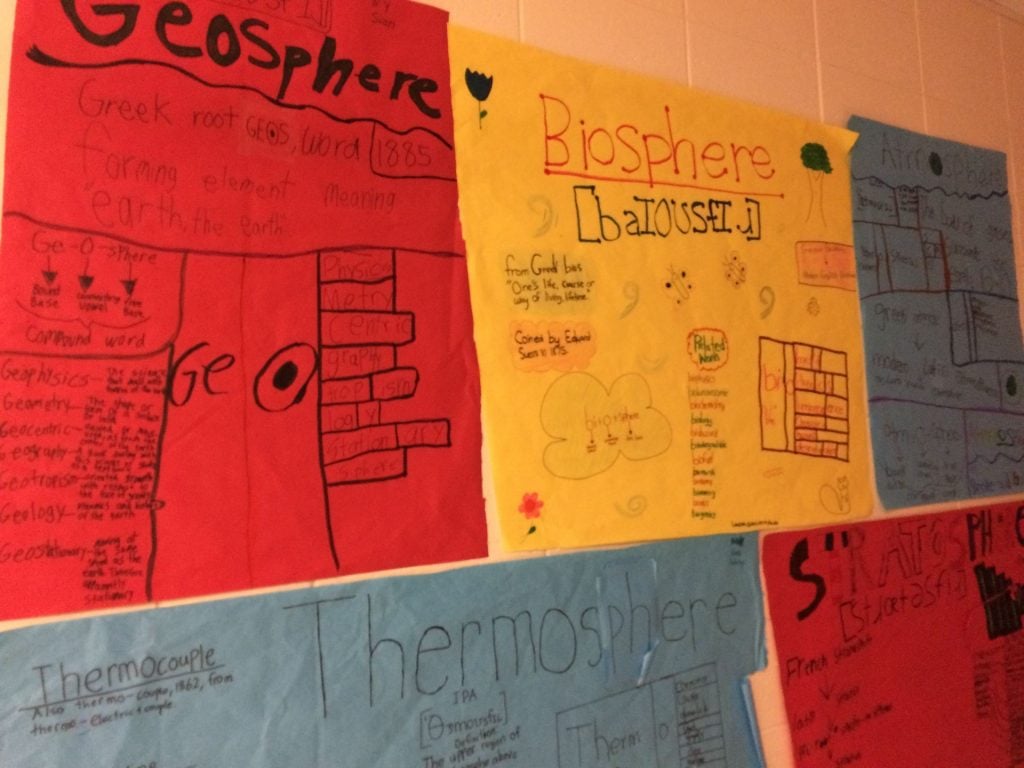

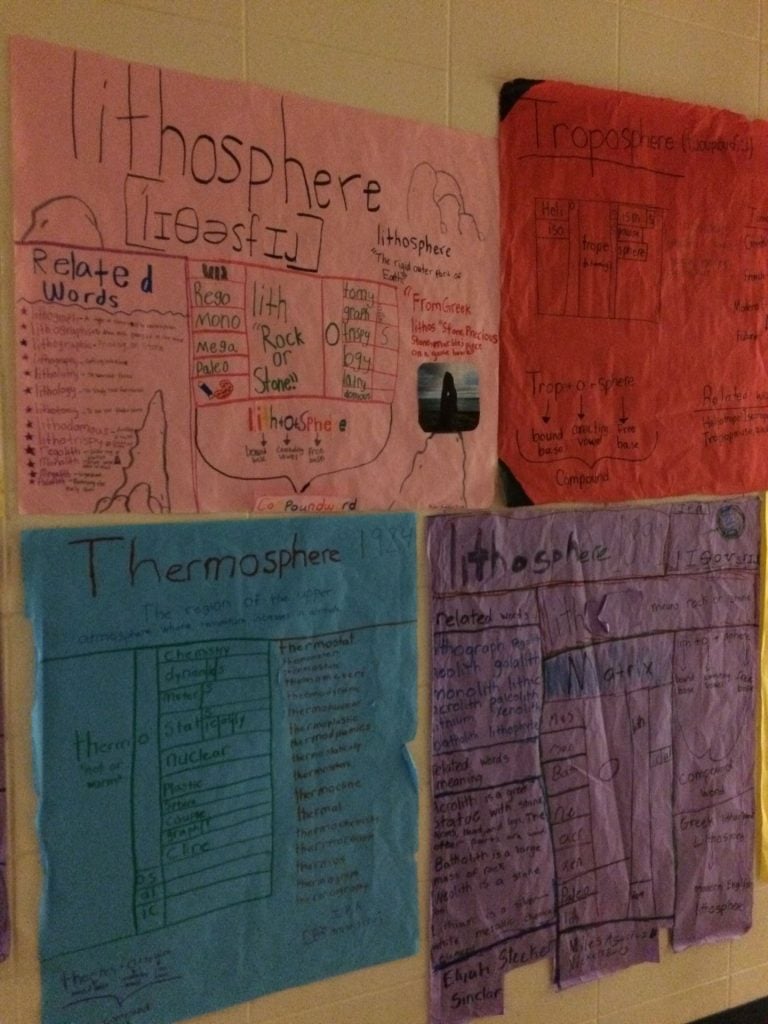

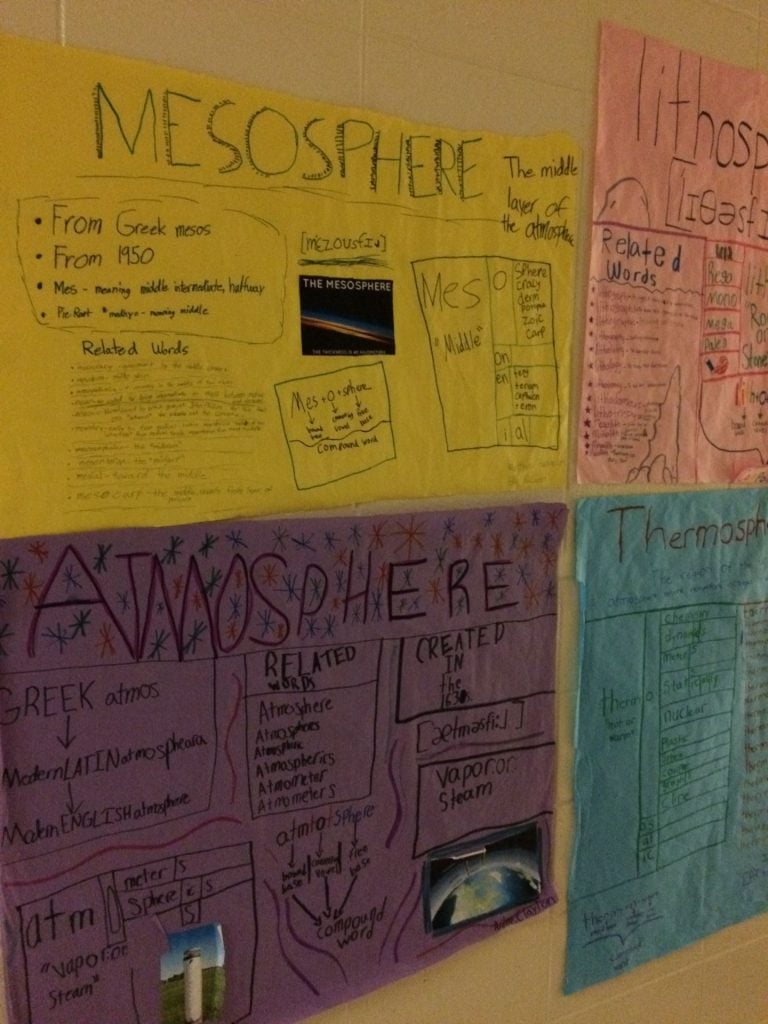

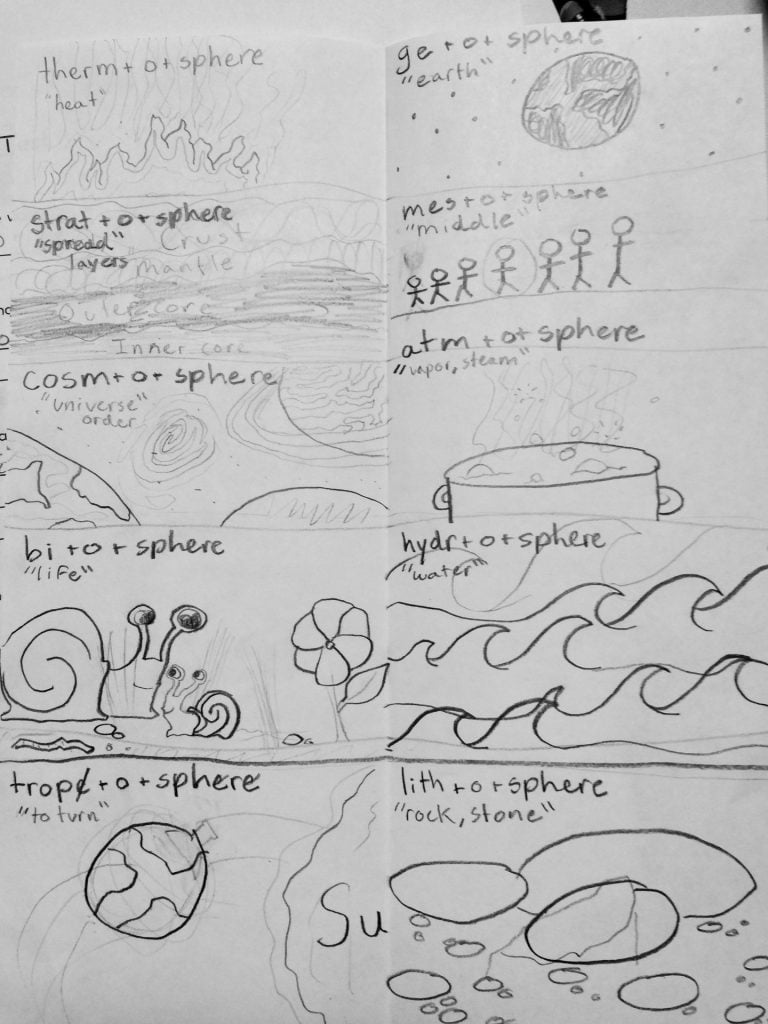

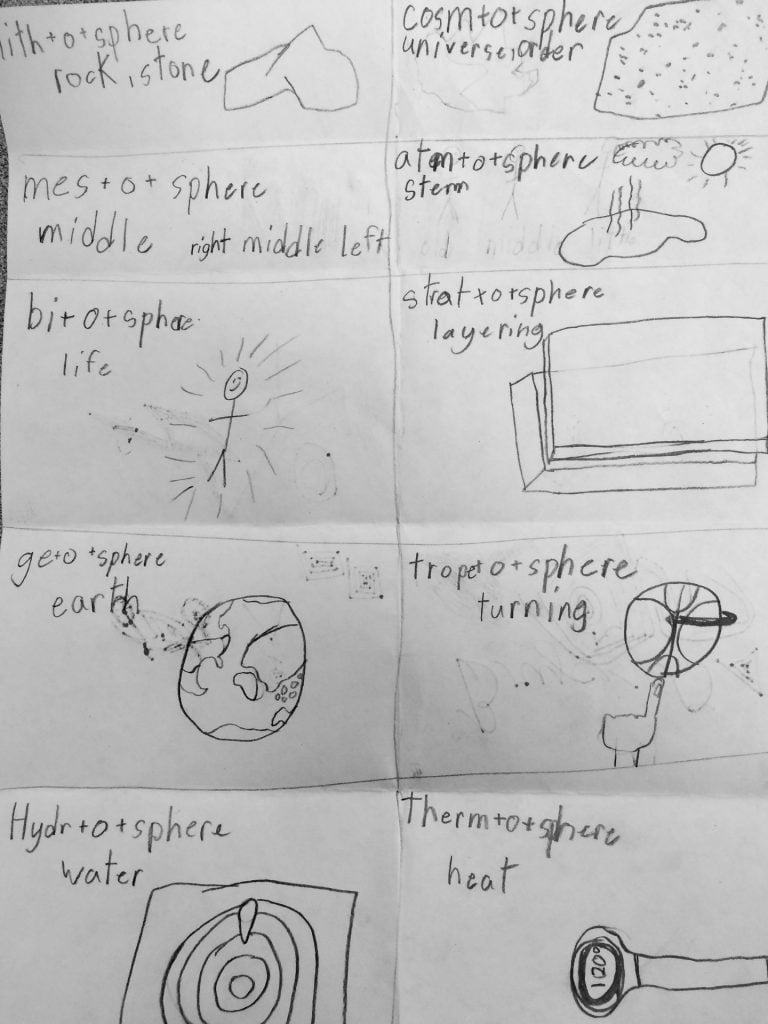

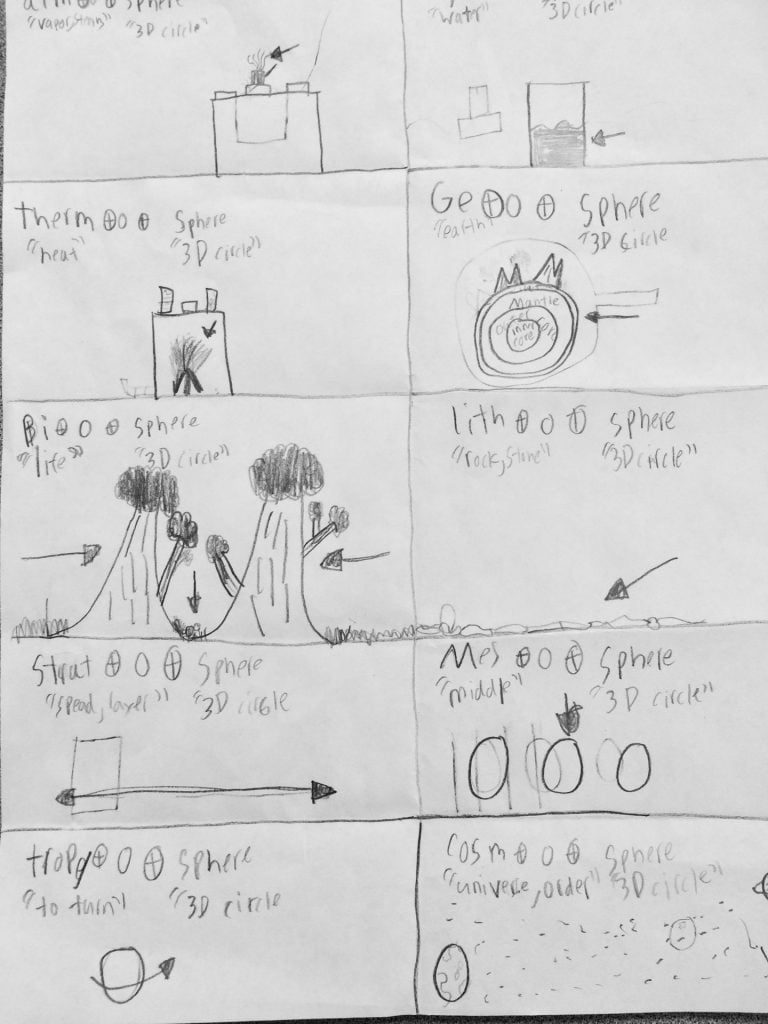

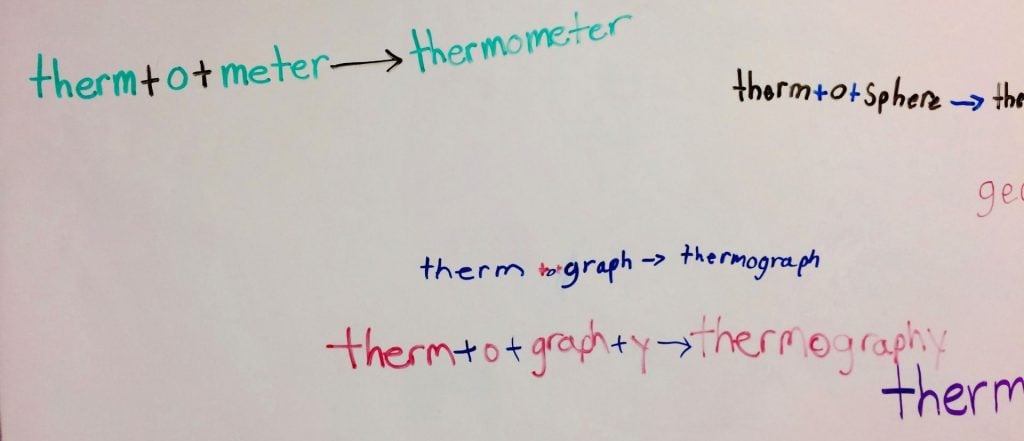

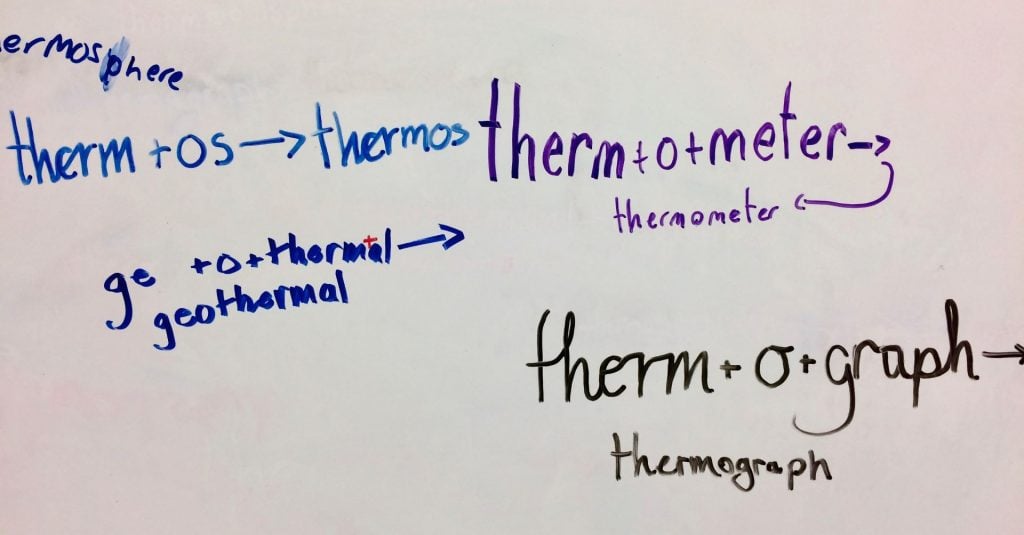

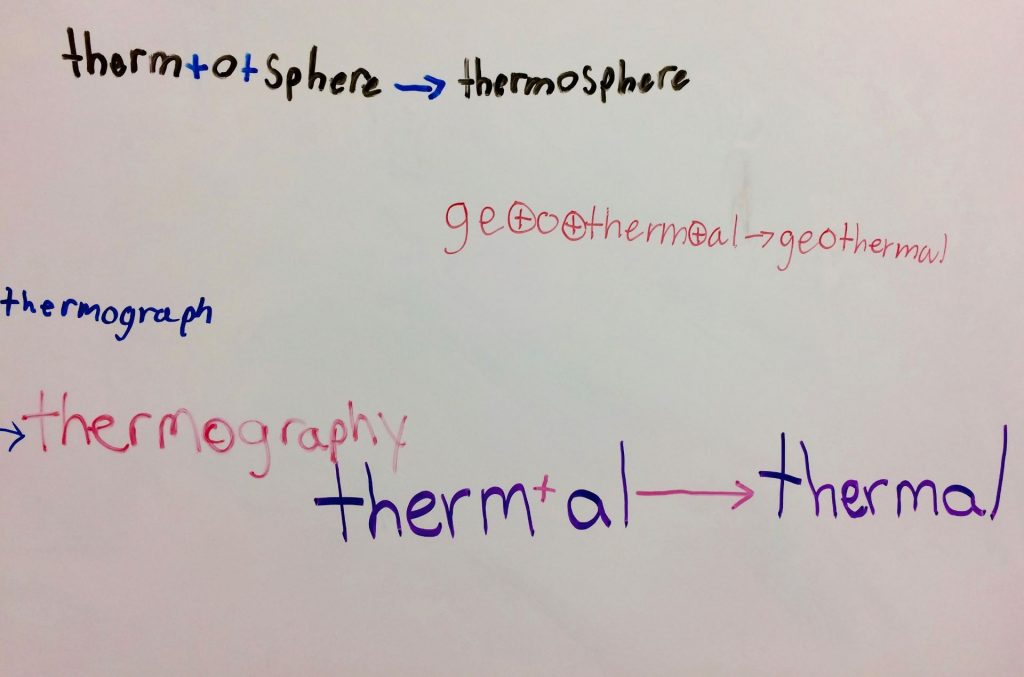

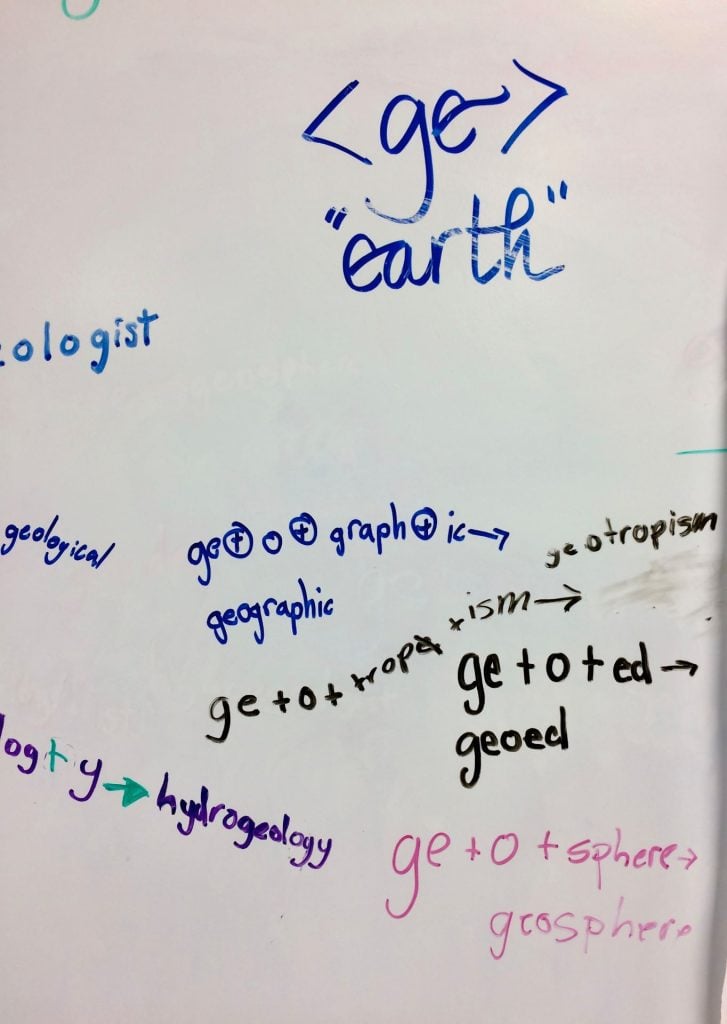

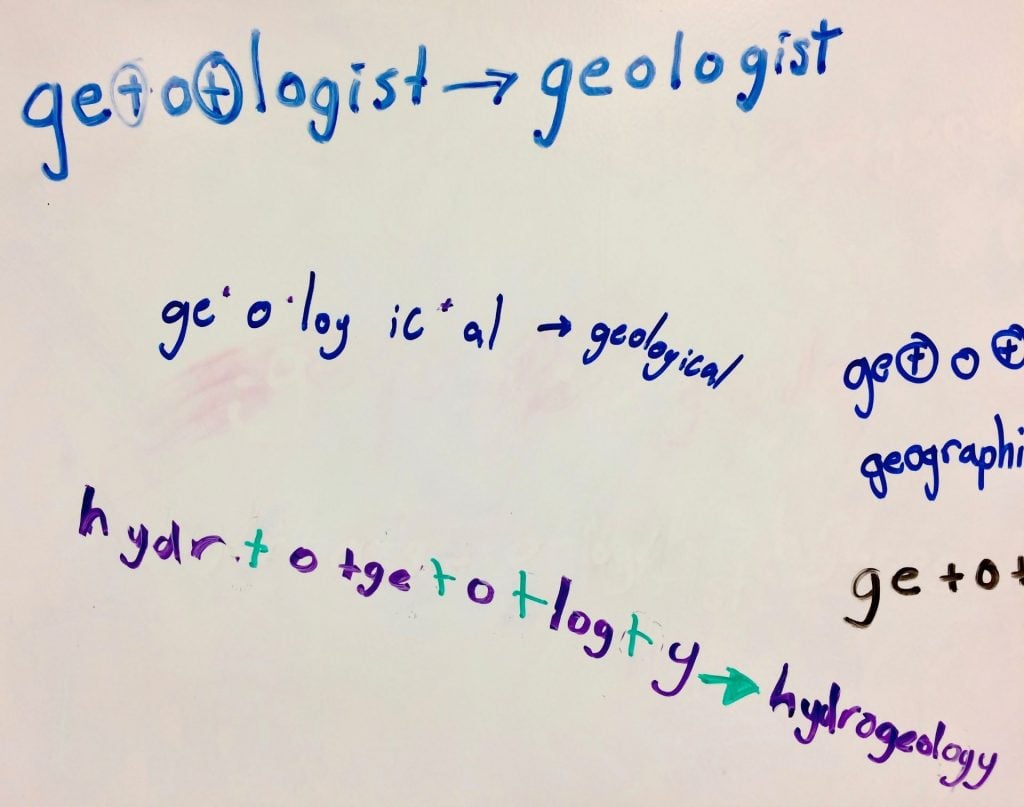

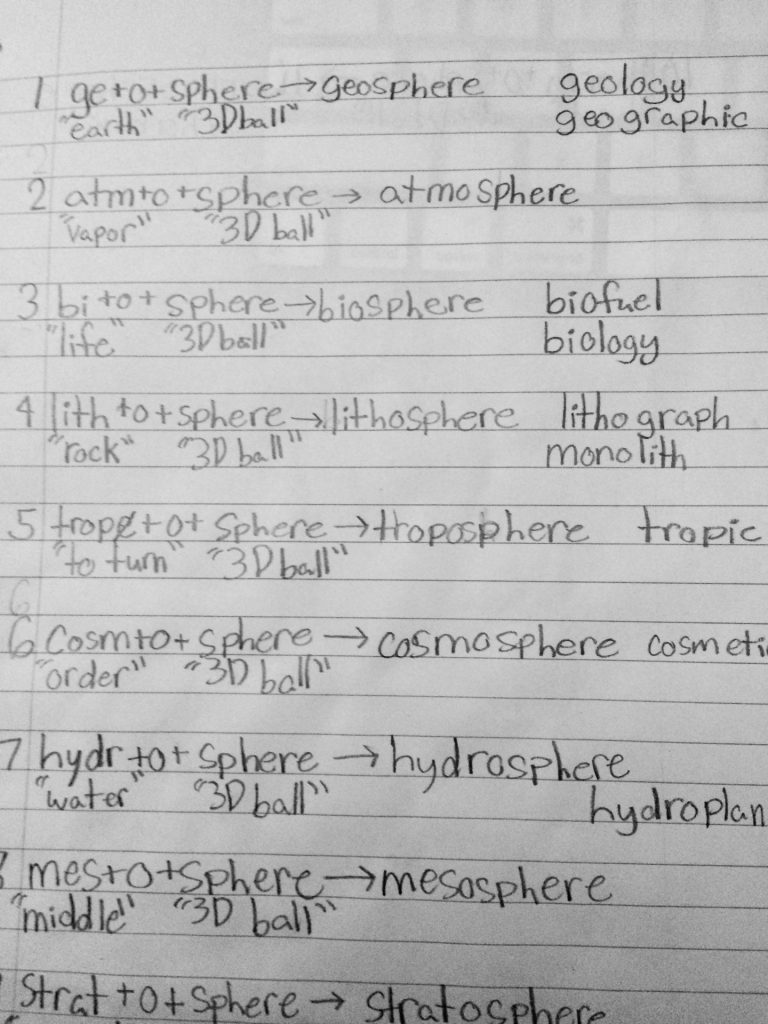

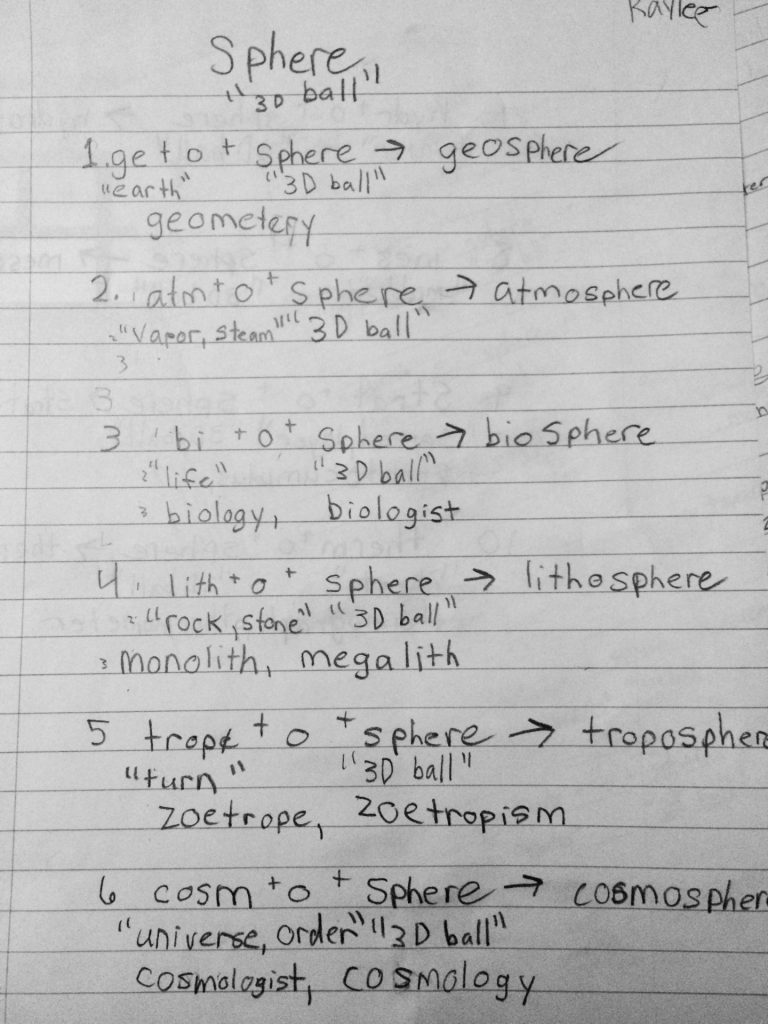

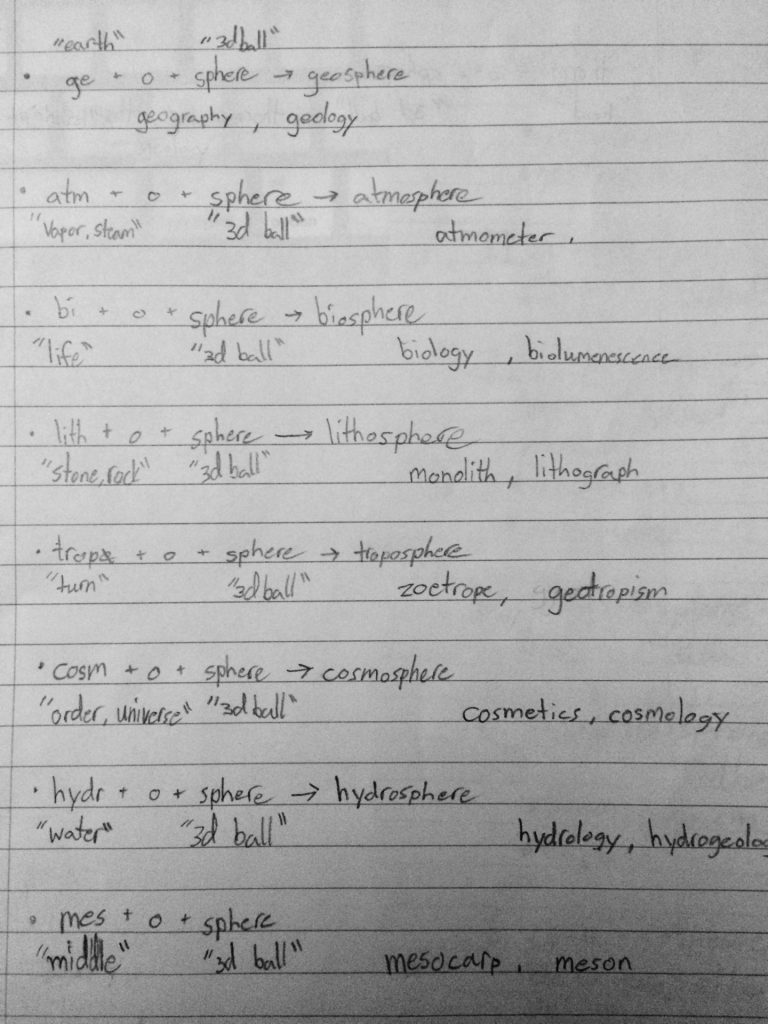

Here are a few of the posters I am speaking about.

It has been two months since we last shared a poster. But we have continued to point out some of these bases to one another as they have popped up in familiar and unfamiliar words.

Last week I decided it was time to assess how well these bases have taken root in their minds. I had the students take a plain sheet of paper and divide it into ten areas. I read aloud each word. I told them that if they wanted to consistently spell sphere correctly (if they sometimes forgot the ‘p’ or ‘h’ or put them in the wrong order) I had a tip. I told them to think of the first phoneme of the word, /s/. They all knew it would be represented by the grapheme <s> and should write it down. Then I told them to think of the second phoneme of the word, /f/. They all knew that in this word (Hellenic) the grapheme that represented the /f/ was a <ph>. That’s as far as we had to go. They knew the rest. It is much more reliable to think of the phoneme / graphemes in this word than to try to remember a string of letters without being taught a reason for them to be in any particular order.

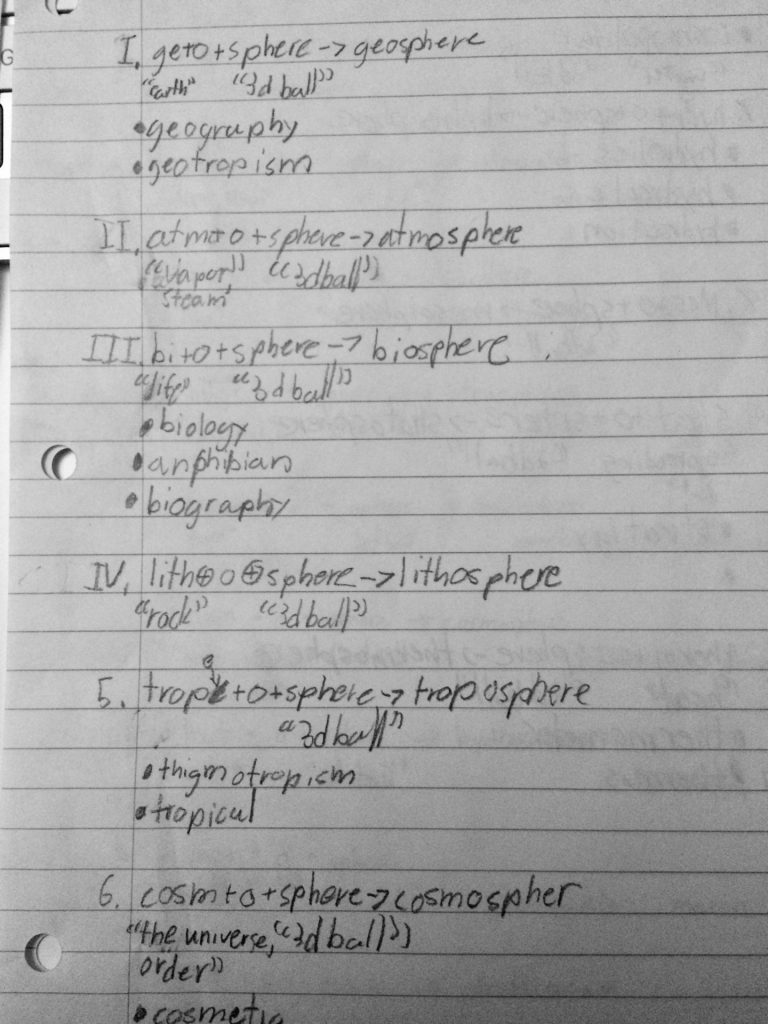

The students chose a square on their paper to write the synthetic word sum for the announced word, the denotation of the base, and then to make a quick drawing of something that they thought of when they thought of the first base. These are called “Quick Draws”. Here are a few of the sheets:

We stopped once we were half way done and took a moment to brainstorm other words that shared each base. With each suggested word, we talked about how that word’s meaning related back to the denotation of the base. So, for example, when speaking of the base <hydr>, students suggested hydrant, as in fire hydrant and explained that water is accessible for firemen at fire hydrants. Students suggested hydrate and dehydrated and explained that the first was taking in water while the second is describing when someone’s body is low on water and needs more. You get the idea.

I told the students to be reviewing these bases and that there would be an assessment in 1 1/2 weeks time.

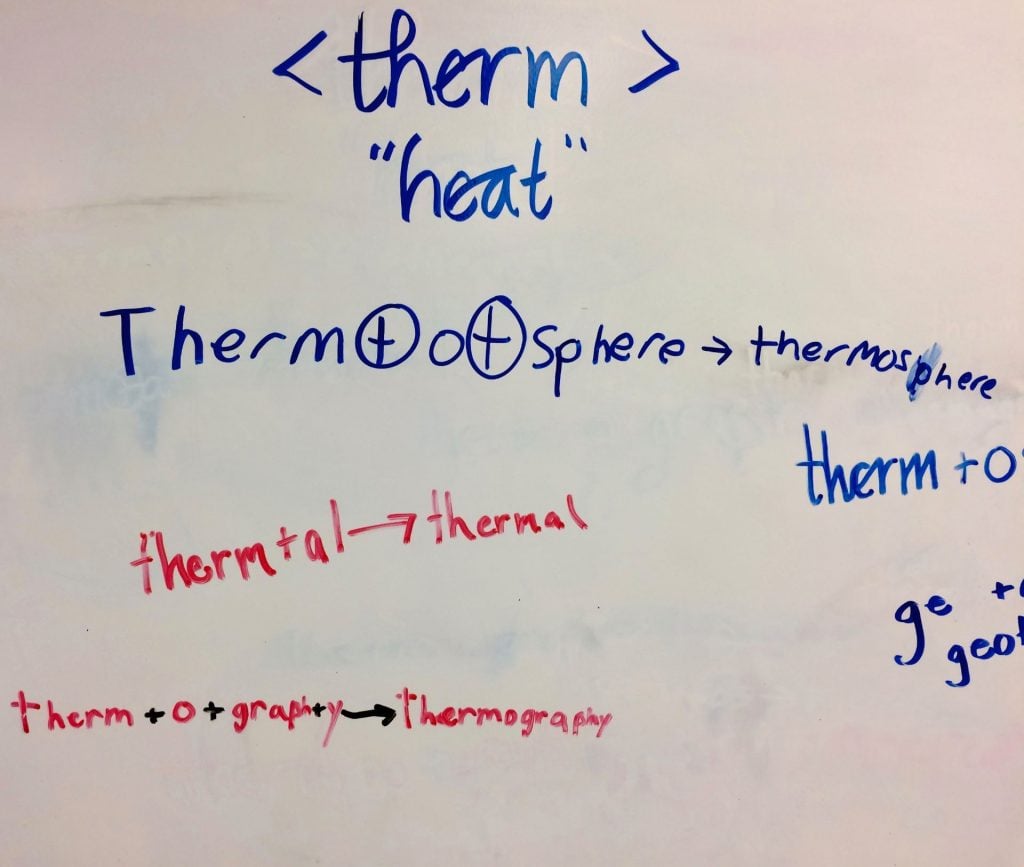

The next day, when they came in, I asked them to get out a piece of lined paper. I told them to write <therm> on the top line with its denotation of “heat” beneath it. This is an activity they have come to be comfortable with. They know that when I read a word, they will write a synthetic word sum. I read aloud seven words that share the base <therm>. Before I began, I reminded them that <therm> is the base. It is not further analyzable, so that means it will show up in a word sum as it is. Affixes may be added to it, other bases may be joined to it, but this base will always be listed as <therm>.

I did not collect the student papers that day, so I cannot show you their work. I did, however, take pictures of the board after the students had volunteered to write the word sums there and read aloud the word sums.

Notice in the picture above that I had both thermograph and thermography on my list. I read thermograph first. Several words later I read thermography. I was curious to see whether or not the students would recognize the base <graph> and its spelling in both, even though that base is pronounced differently in each of the words because of the stress shift. That did not appear to be a problem! After checking out the word sums, we reviewed what a thermograph is. In case you aren’t familiar with one, it is a self recording thermometer. It keeps a continuous recording of what might be a fluctuating temperature. Now if you know that the second base in the compound word thermograph has a denotation of “write”, then thinking about a thermograph as a machine that writes down (or records) the amount of heat (or temperature) makes perfect sense!

As you can see, the students are starting to rely on meaning to help them with their spelling and less on pronunciation. This doesn’t meant they aren’t pronouncing the word as they spell. It means that as they are pronouncing the word to themselves, they are focusing on the morphemes that make up each word rather than on the letter-letter-letter sequence. When I say thermometer, my hope is that they recognize the first base is <therm> and the second base is <meter> and they are connected with the Greek connecting vowel <o>.

In the above picture, you see the words thermal and geothermal. Believe it or not, the students smiled when I said geothermal! They knew both bases from our list and knew how to represent this word in spelling! Then, of course we talked about thermal underwear (after all, what fifth grader doesn’t love it when someone in the room mentions underwear?) and thermal pane windows. Geothermal energy is an interesting thing, so we talked about that as well. Since we’ve just finished our study of the geosphere, we’ve recently been talking about the tectonic plates. It was interesting to note that many of the geothermal energy plants are found along the tectonic plate boundaries!

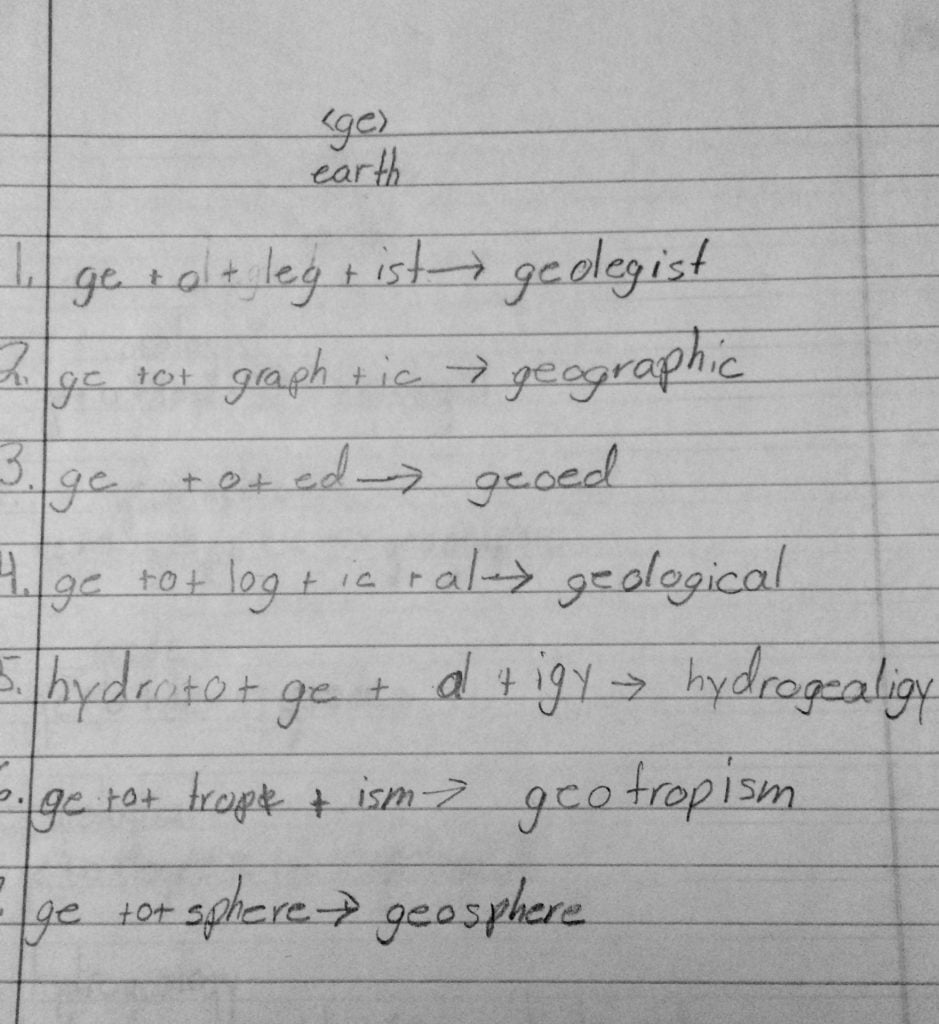

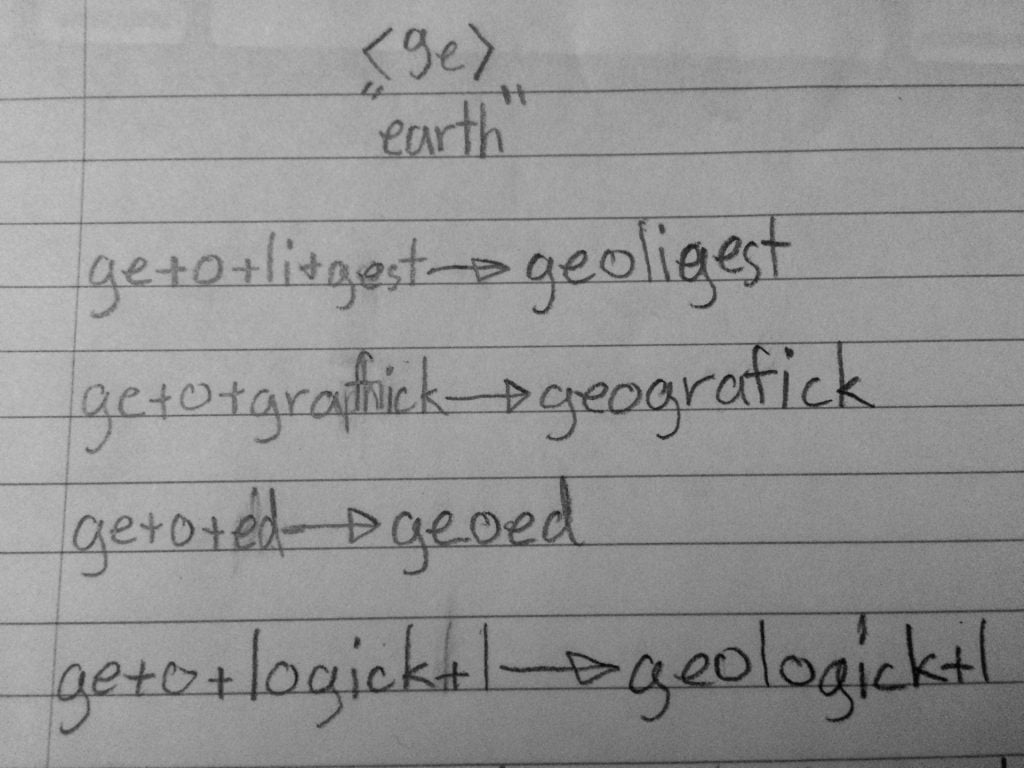

First day back from the weekend! When they walked in, I asked them to get a sheet of paper. Different base, new list of words, new observations. Today’s base was <ge> “the earth, the land”. Today I read the words and the students wrote synthetic word sums like they did the other day. But today I collected the papers before they wrote those word sums on the board. I wanted to see how the individual understanding was growing. I wanted to see which bases /suffixes needed more exposure so they would become recognizable to my students. I wanted to see how many are starting to make the switch from spelling phonetically to spelling morphemically. Here’s an example of what I mean by that:

This student is straddling two worlds. He understands that words have structure, but because he also relies on “sounding out words” in order to spell, this student does not recognize that three of the words have the base <loge>. In the first word, he spells the <loge> base as *<leg>. The good news is that he recognized the <ist> suffix! In the fourth word, he correctly spelled the base <loge>. In the fifth word, he did not recognize <loge> as a base at all. The fact that the <loge> base in all three words has a slightly different pronunciation probably accounts for the difference in spelling here. I think what he did was to guess that there was an <al> suffix and an <*igy> suffix. We have been talking about the <al> suffix recently and how common it is. With more exercises like these, he will rely more on recognizing consistently spelled bases and affixes!

The rest of this list is pretty great! Very few knew that the <o> in geode was not a connecting vowel. I chose that word on purpose. I don’t want to create a false sense of <ge> always being followed by a connecting vowel. If you think about it, this student is busy trying to make sense of the orthography we are studying. He knows that a connecting vowel can connect a base to a suffix. Even though he incorrectly guessed that the <o> was a connecting vowel, he did write that the final /d/ as <ed>.

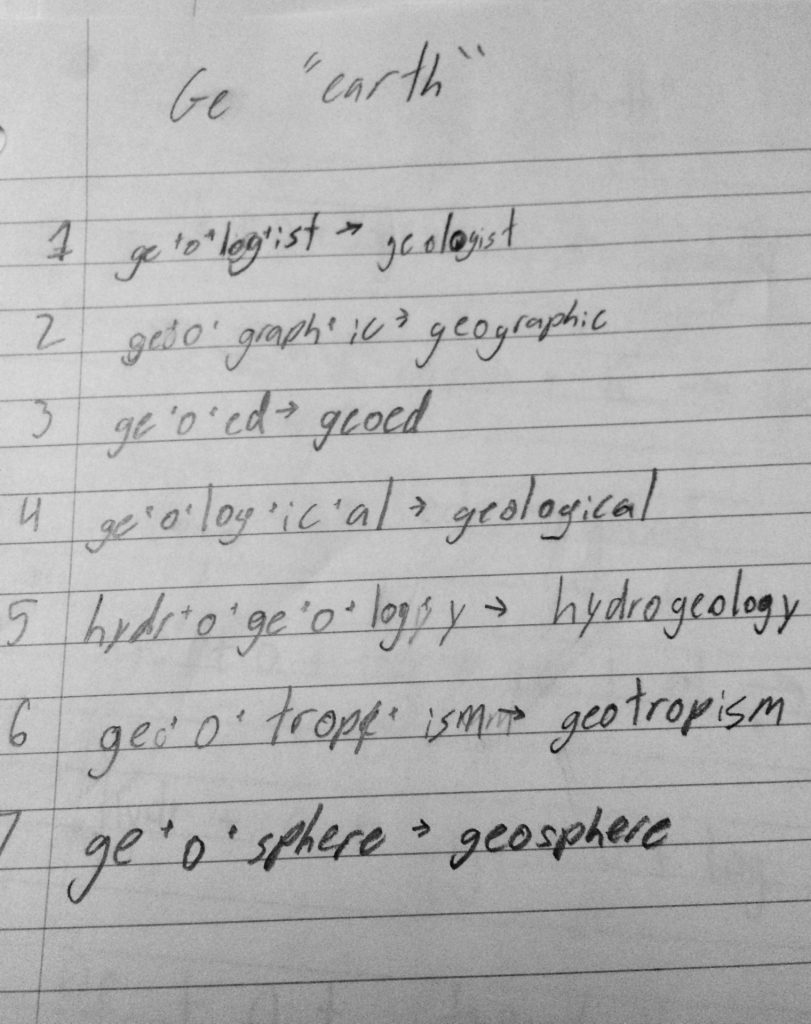

Here’s another I’d like to share:

Look at what is understood and what is iffy. In the first word, this student went back to a deeply embedded strategy – that of breaking a word into syllables to aide in spelling. Except that it didn’t aide him here (and I suspect doesn’t usually). What is interesting about word two and four is that the student knows that when /k/ is final and there is an /ɪ/ preceding the /k/, as in stick, the grapheme representing the phoneme /k/ is <ck>. What he doesn’t realize, is that it is true for a base but not a suffix. So now I know I want to weave in words with the <loge> base as well as words with the <ic> suffix on my next few lists.

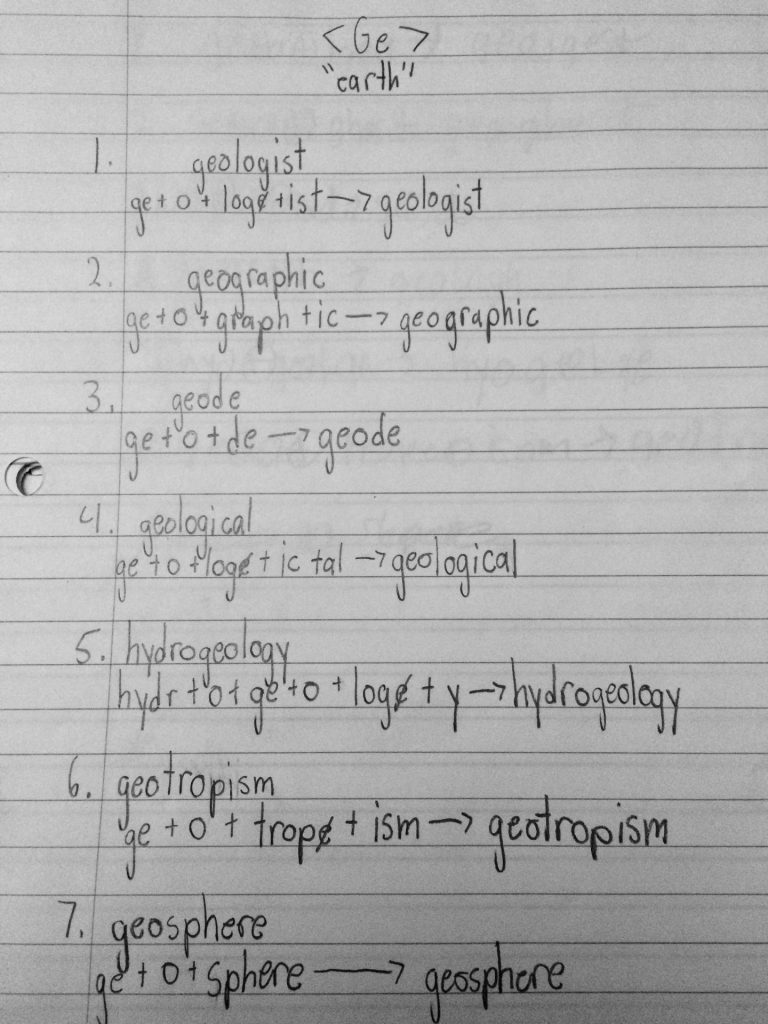

Many other students are feeling confident about recognizing bases and affixes:

The next step was to ask volunteers to write the word sums on the board. Somebody writes it on the board, we talk about it and notice things in common between words on the list. We talk about what each word means, and then another volunteer comes up to read the word sum aloud. As we were discussing the inital large posters that had these bases, we had also discussed the meanings of these words. But I always like to find a word we haven’t talked about yet to see if the students can use what they know about the bases, to give clues about the word’s meaning. The word on this list was hydrogeology. The base <hydr> was one of the bases on the large posters, so I thought this word might feel easy to spell (if they spelled it morpheme by morpheme). They did! And much to my delight, several wondered what it would mean. It was obvious that it had something to do with both water and the earth, but they weren’t sure what. When we searched, we found out that it refers to the branch of geology involving groundwater! Makes so much sense!

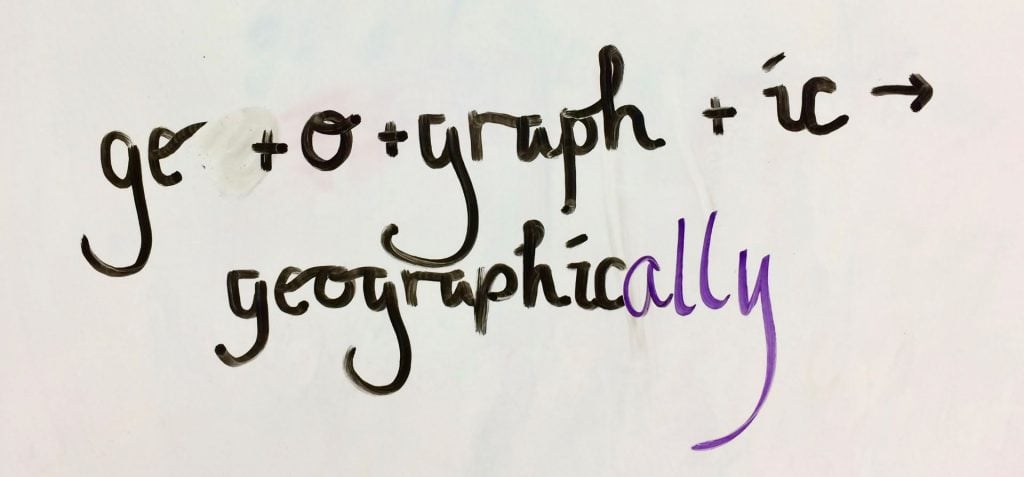

Looking at the above picture, do you see what I see? Just a few days ago, the students were writing the words thermograph and thermography. Today I asked them to write geographic. I’m trying to reinforce what is fresh in their minds.

Isn’t it great that a few of the students are starting to incorporate the Script we are practicing? I love it! Anyway, I paused with this word geographic and asked if anyone had an idea of what would be needed in order to make geographic become geographically. I wasn’t sure if anyone would recognize that we would be adding two suffixes: <al> and <ly>. As it turned out, no one did. The suggestions were for an <ly> suffix only. What a great opportunity to talk about how common it is to add the two suffixes to an <ic> suffix. Offhand I could think of basically, logically, musically, typically, magically, historically, and tragically. Then when we went to Word Searcher and put ‘ically’ into the search bar, there were 240 more! I then wrote the only word I knew of that had only an <ly> suffix added to an <ic> suffix. That word was publicly. We went back to Word searcher and typed in ‘icly’. Publicly was the only word that came up! From Word Searcher, I went to Etymonline. I found out the same thing: publicly is the only example of a word having <ic> and <ly>, but not <al> between them. How interesting!

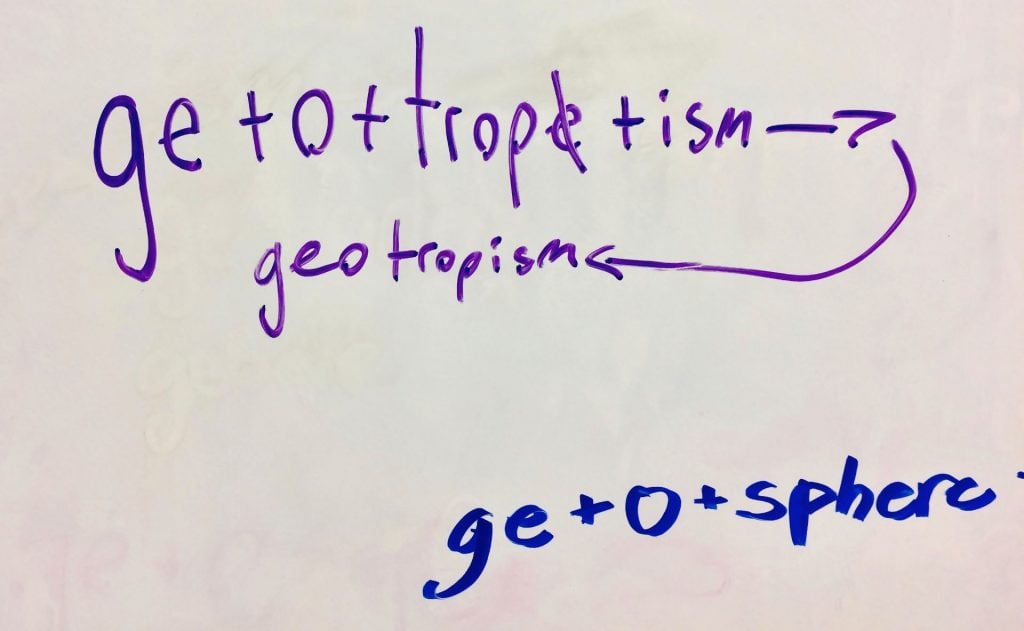

Geotropism is a word we have talked about before. The base <trope> “turning” is another one of the bases that was the focus of a big poster. Geotropism happens with roots. They always grow downward toward the earth. If the plant or stem gets turned for some reason, the roots turn to continue growing towards the earth.

So here’s the assessment. I read each of the ten words. The students wrote the word sum on their paper. Beneath each base they wrote the denotation for that base. If they could think of one or two words that also share the first base, they were to list them. That’s it.

So my classes did very well! They can spell these ten science words! But really? That was only part of what I was hoping to see on these papers. I wanted to see coherent word sums. I wanted to see denotations in quotation marks to signal to all that they are just that – denotations. I wanted to see which of my students have been making connections between these bases and other words we’ve looked at. Are they “getting” that a base with its denotation can be part of a large family of words? After having seen how these eleven base elements can be found in so many other words, are they beginning to expect that of other bases we encounter as well? Are they realizing that seemingly big words are made understandable by first understanding their structure?