Not too long ago I asked my students what they do when they are unsure of how to spell a word. I wanted to know how many strategies they had been taught that might help them. Here is what they told me.

- Sound it out.

- Make up a rhyme or song to help remember how to spell words that aren’t spelled the way they sound.

- Ask someone to tell you how to spell the word.

- Spell it some kind of way and then don’t use it after that.

- If someone suggests that you look in a dictionary, groan loudly because you know you will spend a lot of time at the dictionary and never find the word anyway because you don’t know how to spell it.

We haven’t equipped them very well, have we? I was recently having a discussion with someone who teaches children who are just beginning to learn to read. She told me that “sound it out” is a strategy for reading, not for spelling. Hmmm. When are the children ever told that? When are the people who teach the children ever told that? What are children offered instead? If it is recognized by both adults and children that “sound it out” isn’t reliable, what else are we teaching in its place?

This is an important question to ask. I need to know how well equipped they are for what I will be asking them to do all year — which is to write with minimal spelling errors. Those students with remarkable memories smile, feeling quite confident that they are pretty good at spelling. Those who can’t seem to remember the order of the letters in a word (even when they’ve written and rewritten the word twenty times), feel the opposite. They feel frustrated and dumb. It’s not uncommon to find out that those students started hating writing long before now – especially if they can’t read their own writing! I have a student currently who hates to go back and fix up his spelling so much that he insists on getting the right spelling for each word as he writes each sentence. As you can imagine, his ideas don’t flow very well in his writing. His mind is on spelling more than it is on the ideas he is trying to express. He has entered 5th grade absolutely hating writing because of spelling.

It pleases me to no end that I can offer my students real help. This is the year that they will learn a strategy that will actually help them understand spelling. And when they understand a spelling, there is a larger likelihood that they will remember the spelling of the word. They will learn how to spell words and not remember working at it to do so! Sounds hard to believe, doesn’t it? Listen to these two students.

The first student clearly expresses that learning to spell a word and then having to attach meaning to it is completely different than learning to spell a word based on that word’s structure and the denotation of its base(s). Her second grade memories illustrate the two things as separate activities. By studying orthography and noting the sense and meaning that is inherent in the base(s), she understands the spelling of the word AND its meaning, realizing that the meaning is represented in the spelling. Learning the word’s structure and meaning, and then noting the connections of the word’s base(s) to other words that share that base, is a revelation to anyone who has wondered about the English spelling system. It is as powerful for adults in remembering a word’s spelling and meaning as it is for children.

The second student in the video clearly expresses how effortless remembering the spelling of a word can feel. Notice that I did not say “memorizing a spelling.” That is what students do prior to coming to my classroom. It happens when teachers don’t have an understanding themselves, yet need the students to spell words accurately. I’m pretty sure that a large number of you (I’m including myself in that group) grew up memorizing spelling without any further understanding of that spelling. You can’t imagine what more there is to learn until you actually engage in investigating a word for yourself. The second student in this video has found this type of looking at words to be so helpful! As she says at the end, she learned how to spell the words she investigated and she didn’t even know she was! Every year my students tell me they know they are better at spelling than they were at the beginning of the year. If they feel empowered, isn’t that what it’s all about?

This next video features a student who has never struggled with memorizing the spelling of words. So how does studying orthography benefit her?

Even when our goal of having students know the spelling and meaning of a word is met, there is much we have left out! Here is a student that can easily memorize both the spelling and meaning of words she encounters. But even she recognizes that by studying orthography she is engaging in the learning in a way that she has not been asked to do before. “Here’s a list of words. Memorize them and then write out definitions.” Sound familiar?

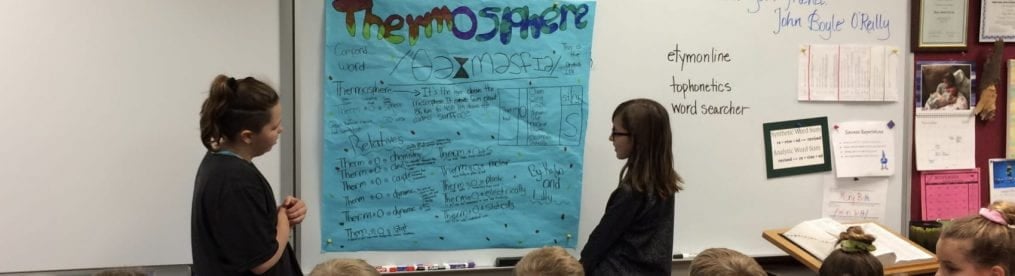

I find that students are engaged in the word inquiries we conduct because they are leading the investigations. They are not being asked to regurgitate information that I collected for them about words. They are not matching definitions I wrote to words that I want them to know. They are creating hypotheses about a word’s structure. Then they are using resources (authentic, reliable, and not necessarily made for kids) to understand the information for themselves. Yes, I need to guide them in their use of those resources at first. But it doesn’t take long before they are independently finding out the story and word sum of a word. And in the course of doing so, they are understanding and learning its spelling.

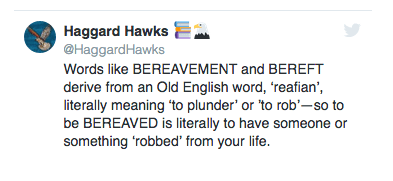

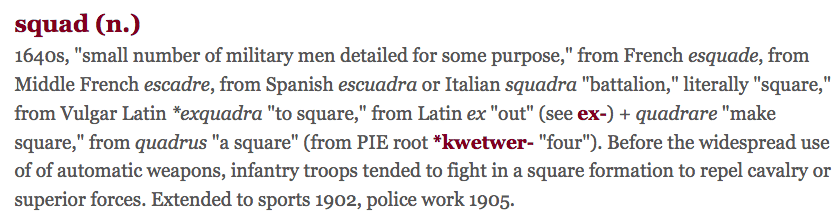

Recently I saw a post from Haggard’s Hawk . (Click on the name to visit the Home Page. Haggard’s Hawk posts things on Facebook, Instagram, blog, and Twitter. I saw this on Twitter.) I find Haggard’s Hawk to be a fascinating source of word etymology. Paul Anthony Jones has written eight books that you can also check out at the link I have provided. So here is a screen shot of the post I saw:

My point in sharing this post is that until I looked at the etymology, I thought of the words <bereavement>, <bereaved>, and <bereft> as meaning someone is feeling sad because a loved one died. Adding the sense of “plunder” and “rob” amplifies (in a way) what bereavement means. My mother passed away several years ago now. Describing my bereavement as the feeling one has when being robbed of something is so much more accurate than describing what I was feeling as “sad.” Sad is used generically for hundreds of situations that happen every day. Being robbed of someone has that sense of unexpectedness and outrage (in a way). It truly feels as if I was robbed of having my mother in my life. My life has not been destroyed because she died, but I do feel a sense of my life having been plundered by it. I’ve had to try to put things back that were set askew. But something big will always be missing. And there’s that sense of having experienced being robbed.

Do you see how looking specifically at a word’s base element and its denotation can bring depth to a word? Having spent seven years learning about words with students, I am only more excited each and every day. I will never know the story of every word, but I will always be delighted to know one more. In the classroom, it is like the student in the video says, “Mrs. Steven learns it along with us. She just doesn’t have all the answers, and that’s really fun.”

So let’s get to the nitty gritty of this post. I teach my students to identify the structure of a word. I teach them that words are made up of a string of morphemes. Each morpheme contributes to the meaning of the entire word. The morpheme that carries the main sense and meaning of the word is the base element. A word that has more than one base element is a compound word. Most people understand this. The part they might not understand is that not all bases are free bases. What I mean by that is that not all bases can be words on their own. A base like <hope> is a free base because it is a recognizable word on its own. We could add a suffix, but we don’t have to in order for it to be a word. A base like <fer>, however, is a bound base. We never see it as a word on its own. We see it when it is paired up with affixes. You’ll no doubt recognize it in <offer>, <different>, and <conifer>. It has a denotation of “carry.” If I was guiding an investigation of <fer>, I would definitely encourage my students to find related words as I have done here. Then I would ask them to tell me how that sense of “carry” is there in the word. Sometimes it is a strong sense in the modern word, and sometimes it is faint. But it is always there. Check out this student’s enjoyment of learning about these connections.

This is another example of a student who didn’t necessarily struggle with memorizing spelling words. Yet here she is, excited to really understand that words have a structure and a history, and that by using the sense and meaning denoted in the base along with the sense that affixes contribute, she can understand the meaning represented in the word’s spelling! This is her “Eureka” moment and she looks forward to making the same comparisons and connections with each word she investigates!

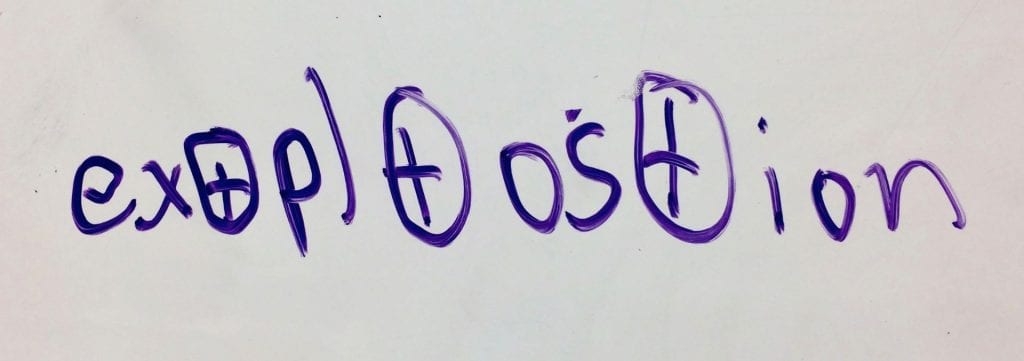

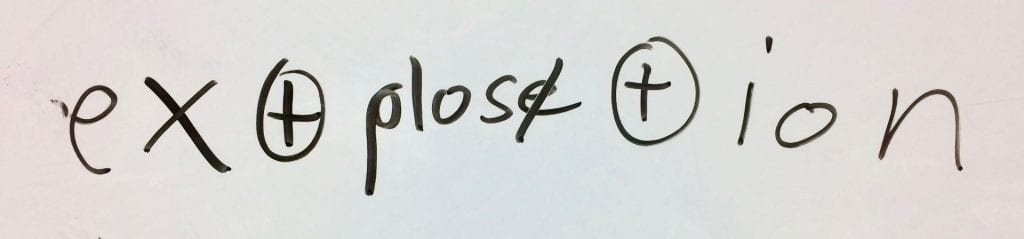

In order to strengthen each student’s ability to create a logical hypothesis, we do the following. I write a word on the board and ask the students to think about it for a minute. Then I ask for volunteers to write a word sum hypothesis on the board beneath it. Here is an example:

As each hypothesis is added to the list, I will point out certain things we are seeing. With these three hypotheses, I noticed that all three have identified <ex-> as a prefix. I will now ask students to brainstorm other words that seem to have an <ex-> prefix. When students have collectively thought of three or more, then we decide that identifying <ex-> as a prefix is a logical idea seeing as we know it to be a prefix in other words.

Next I would point to what has been identified as suffixes. In two of the words <ion> has been suggested and in one word <sion> has been suggested. Now I ask the students what they think of those two suggestions. Can they think of other words that have either an <ion> or <sion> suffix? Since we recently took part in an activity in which students were focused on finding certain suffixes, a few of the students recognized that <-ion> is a suffix in <adoption> and in <action>. We thought of <expression>, but realized that even here, the suffix would have to be <ion> since the <s> before the <ion> in that word is part of the stem <express>.

That left us to consider whether the first or second hypothesis was more likely based on what we knew. No one was familiar with <pl> or <os> as morphemes on their own, but that doesn’t mean that neither of them is or isn’t a morpheme. Next we brainstormed words related to <explosion>. The students thought of:

<explosive>

<explosives>

<explosiveness>

<explosively>

<implosion>

Our related words list gave us evidence that the <ex> was a prefix because we could see that it could be replaced with an <im> prefix. We also saw the evidence that <ion> was a suffix because it could be replaced with <ive>. We were pretty sure that the base in this word was <plose>. A look at Etymonline revealed that this word’s furthest back relative was <plodere>. When I see that final ‘ere‘ on a Latin ancestor, I recognize that this was a Latin verb and the ‘ere‘ was an infinitive suffix. When removed, it reveals the stem that came into modern English as a base element. You have probably already noticed, however, that when we remove the ‘ere‘ we are left with <plode> and not <plose>. These are alternant spellings of the same Latin verb meaning “drive out with clapping.” You see, this verb was originally used in the theater. I bet you can imagine an audience exploding with applause. By the way, <applause> and <applaud> are related to these. They continued to be used in a theater sense, and <explosion> and <explode> began to be used in other situations as well.

The evidence we gathered supported the word sum <ex + plose + ion>.

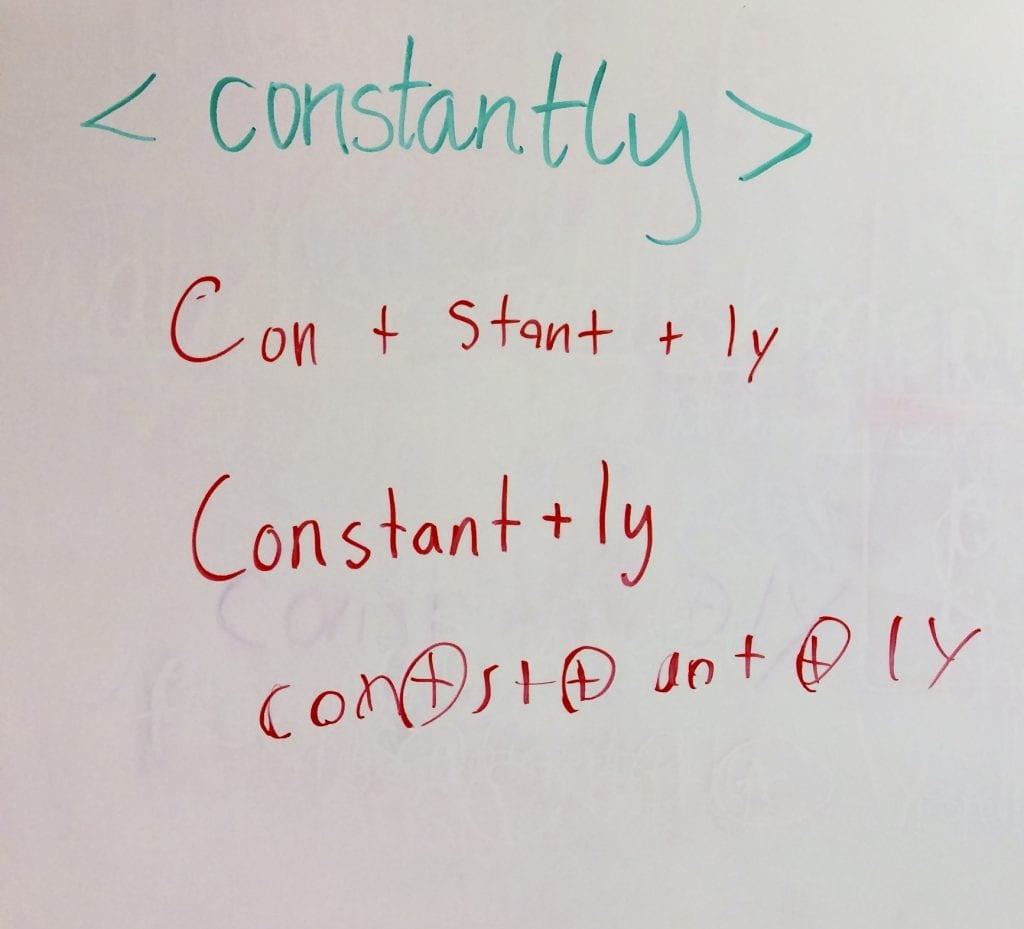

Giving the students opportunities to hypothesize word sums encourages them think about many of the words they encounter in and out of school! It is not uncommon to hear from either students or parents about word conversations that took place in the car or at the dinner table! Here’s another example from last week. I put the word <constantly> on the board. Here are the word sum hypotheses the students created:

Because we had done this activity several times before, I did not begin by sharing what I noticed about these hypotheses. Instead I asked the students what they noticed about the three word sum hypotheses. “What do you see that you agree is a logical hypothesis for either an entire word sum or part of a word sum.” The first person noticed that all three hypotheses suggested that <ly> was a suffix. Other students easily thought of words with an <ly> suffix (lonely, quickly, happily). It may have helped that we looked at a list of words with <ly> suffixes the day before. And that may be why I chose a word with that suffix for today. A little reinforcing is always a good thing!

Then someone noticed that two of the hypotheses had <con> as prefixes. So we did some brainstorming again and thought of concert, construction, contract, concussion and congress. The students weren’t sure whether <con> really was a prefix in concert and congress, but they could think of replacing the <con> with <de> in <construction> (<destruction>), removing the <con> and adding an <or> suffix to <contract> (<tractor>), and replacing the <con> with <per> in <concussion> (<percussion>).

I specifically asked what everyone thought about the second word sum – the one that read <constant + ly>. I wanted to point out that when you absolutely cannot point to anything you recognize as a possible morpheme, then this would be a good choice. It is far better to “under-analyze” than to “over-analyze” without evidence. When you first start this activity with your students, you may notice that they assume that every two letters is a morpheme. Sometimes it is obvious to me that they are breaking the word into syllables, but sometimes it’s not even that. They just have no idea what’s what yet. They do not recognize enough affixes or bases. That is why I choose words that reinforce affixes we’ve already noticed. That is also why I show them how to think logically as they are thinking through the hypothesis they intend to propose.

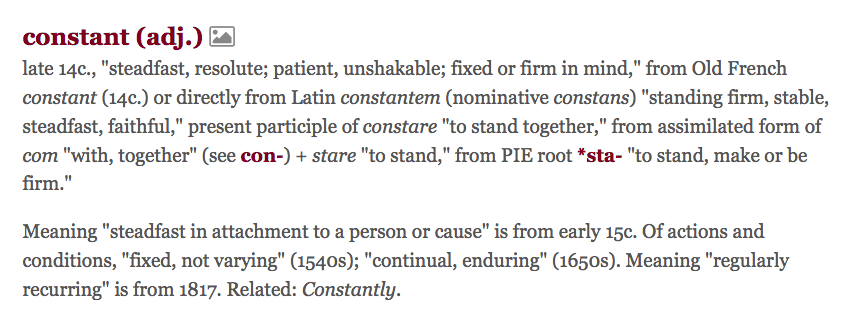

The last two things to consider then are the possibility of a <stant> base or an <st> base and an <ant> suffix. My first question to the class was, “Can you think of any words with an <ant> suffix? Can we provide evidence that it might be a suffix?” After some thinking time someone offered up <pleasant>. Then the words <migrant> and <pollutant> were named. That was enough evidence that the <ant> might be a suffix. But then that left an <st> base. Is there such a thing? I thought back to the moment when the student wrote this particular hypothesis on the board. Another student kind of sniggered from his seat as if suggesting an <st> base was going too far. It does sound improbable, doesn’t it? We were now at the point when it was time to go to a resource. I called up Etymonline and shared it on the Smartboard with everyone. I searched for <constantly>. This is what came up:

The students were so perplexed. “What? Why does sourball come up?” I told them to read what they were looking at and then to raise their hand when they had an idea why this word came up in the search. It didn’t take long at all before they saw the word <constantly> in the entry for sourball. I then told them how glad I was that this happened. It just shows us that when we list a word in the search bar, the program looks for that word in all the places it exists on the site!

My next question was what to do next? How should I alter what I have in the search bar so we can keep going with our investigation? As if in harmony, most all of the students responded with, “Take off the <ly> suffix.”

As we read through the entry together, I pointed out that this word was first attested in the late 14th century. It is obviously a very old word. Then I went on to say that at that time this word was used to mean “steadfast, resolute; patient, unshakable; fixed or firm in mind.” I paused to think out loud and to model what I hope they do when they read during research. “Is that how we still use this word? What is something that we might describe as constant?” After a moment of thought someone said that a noise could be described as constant. So we talked about a dog who is constantly barking or an alarm that is constantly going off earlier than it should. Then we thought of the 14th century sense and meaning of this word – unshakable, fixed. We knew that we still use this word in the same way. It was time to keep reading.

Next we noticed that this word was either from Old French and had the same spelling then as we have today, or it was from Latin constantem with a sense and meaning of “standing firm, stable, steadfast, faithful.” As I kept reading, I saw the words “assimilated form” and pointed that out. “Look here! The word is from the assimilated form of com meaning ‘with, together.’ Then it says, ‘see con-‘. What do you suppose that is evidence of?”

Again they all responded, “A <con-> prefix!”

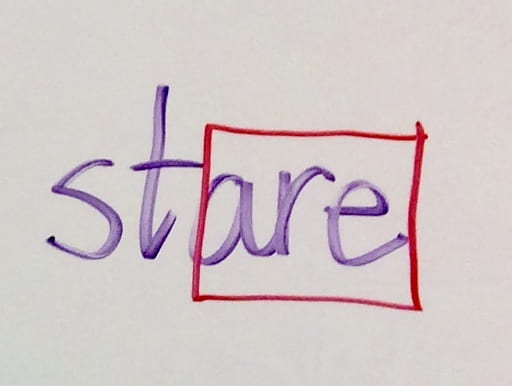

“Now keep reading. Do you notice how this is from an assimilated form of com + stare “to stand?” Do you see that? Well, let me tell you about that Latin verb. I happen to know it is a Latin verb because I recognize the infinitive suffix on it. You know how we have certain suffixes that we recognize as suffixes we use with verbs? You know, like <ing> sometimes and <s> sometimes? Well in Latin, one of the suffixes found on the verb in its infinitive form is an ‘-are.’ When we remove that suffix from this Latin verb, we see the Latin stem that came into Modern English and is now a base element.”

I wrote the Latin verb stare on the board and boxed out the infinitive suffix so the students could see what I was doing. In this way they could also see what would be left without the Latin suffix.

There was a bit of excitement mixed in with a bit of “I don’t believe it” when they realized that the Modern English base is indeed <st> and has a denotation of “stand!” The next step, of course, was to put together what we knew the base meant along with the sense carried by the prefix. We had a literal sense of “stand together.” Looking back at the way <constant> has been used in the past, several students right away spotted the words “standing firm” and “fixed.” Again we could relate these senses to how we use the word <constant>.

It was time to draw everyone’s attention back to our three hypotheses. It is always important to point out that there aren’t any right or wrong answers on the board. There are only hypotheses that can be supported by evidence and hypotheses that can’t. Nurturing that understanding builds an atmosphere in the classroom that is free of judgement. That is huge! In this case, there are two that we can support with evidence, and one that we can’t support with evidence. But even the one we can’t support with evidence had some logical and evidence-supported morphemes in it!

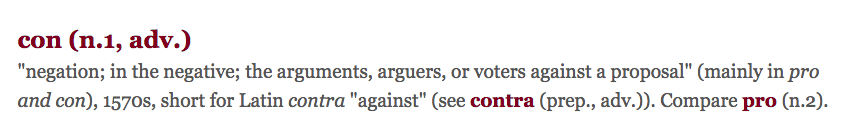

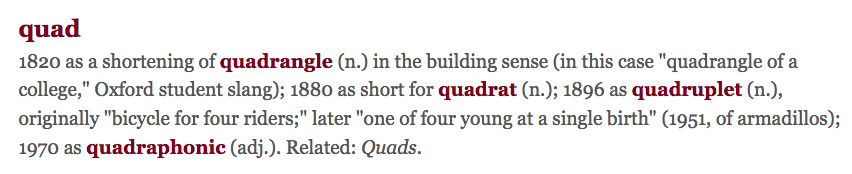

So as we were wrapping up this activity, a student in the back row raised her hand and asked, “What about pros and cons? Is the <con> in this same prefix, or is it a clip of something?”

The smile on my face was immediate! What a thought provoking question! I paused for a bit before saying, “I hope you don’t mind, but I’d like some time to think about this. Maybe others in here feel the same way. Would you please write your question over on the Wonder Wall? We’ll look at this tomorrow. In the meantime we can all have some time to think about it.”

When this group of students came in the next day, I started by asking how many had given this some thought. At least eight hands went up. I was impressed. One student explained that she had laid in bed the night before trying to think of what <pro> and <con> might be a clip of. Another student wondered if <pro> was a clip of proactive and that maybe <con> was a clip of conflict. Interesting. Someone else piped up and offered that <pro> might be a clip of proficient.

At this point, I said, “Let’s back it up a second and make sure we have a sense of what we mean when we use this phrase. Is there another phrase that is sometimes used in place of this one?” Students replied with:

“How about advantages and disadvantages?”

“Or pluses and minuses?”

Next we thought of a scenario in which we might make a list of pros and cons. Examples from our discussion included deciding whether or not to get a new pet and convincing parents to start/increase an allowance. Now I felt like we were ready to see what Etymonline had to say. We began by looking up <con>.

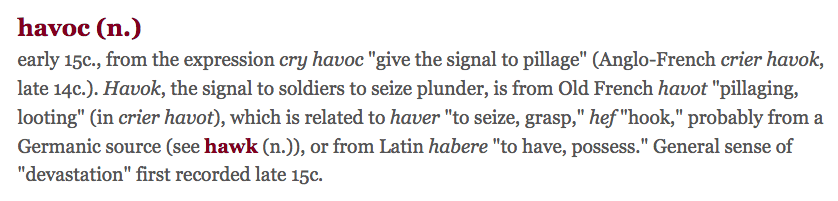

Immediately it was agreed that this fit our search. The first words “negation; in the negative; the arguments” were exactly what we thought of when we thought of the “cons” of a proposal. As we continued to read, we were surprised to see “mainly in pro and con.” I paused to think aloud again. “So this use of <con> to mean something negative is mainly used in the phrase pro and con. Interesting! And look! It’s been around since the 1570’s! Isn’t it surprising that this phrase is that old?” But little did we know that the most interesting part was yet to come. The very next words told us that <con> was indeed a clip. It was a clip of contra “against.”

Before we used the link to find out more about <contra>, we finished reading the entry and saw the direction to compare <con> with <pro>. We decided we would come back and do that after we looked at <contra>.

What we found at the entry for <contra> was that this is a free base with a denotation of “against; on the opposite side.” What really caught my eye was the list of related words. I chose three to talk about, thinking that those three might be familiar to my students. The first was <contradict>. I explained that the bound base was <dict> “say.” The example I used was, “If I were to say that today was Friday and someone were to say it was Thursday, I might tell them not to contradict me.”

The second word was <controversy>. To illustrate this, I brought up the current issue of climate change. I told them that this is a controversial issue because some people believe it is a problem and some people have the opposite view. They do not believe it is a problem. Since both sides are feeling strongly, this becomes a controversial issue.

The last word we spoke about was <contrast>. A student shared that when we point out contrasts we are pointing out differences. Great! But here was an opportunity I was not going to miss. “Does anyone have a hypothesis about what the word sum for <contrast> might be? Think about the entry we are looking at.

A student raised his hand with movements of urgency. “<contra + st>!” Eyes lit up everywhere.

I suggested we look at the entry for <contrast> to see if we could support this hypothesis with evidence. Sure enough! This word is from Latin contra “against” and Latin stare “stand.” How cool that we found another word with an <st> base already! It was great to be able to reinforce how I knew that the base was <st>.

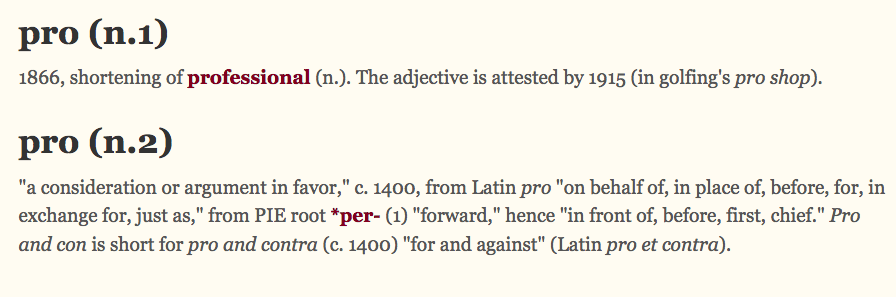

It was time now to go find out about <pro>. I took them back to the Etymonline entry for <con>. I wanted to point out something. Right behind the link to “Compare pro,” there was a set of parentheses with (n.2). I asked, “What do you supposed that means?” The silence that followed made me glad I had asked. It is opportunities like these where I can make their individual visits to Etymonline more productive. I asked if anyone ever noticed that sometimes a word is listed twice in a dictionary because it has two different meanings. Many had. That was enough to trigger some understanding that (n.2) meant that <pro> is a noun and we would be looking for the second entry.

Even with pointing out that we would be looking for the second entry, several students shouted out that <pro> was a clip of <professional>. So we read together the second entry and realized that “a consideration or argument in favor” is the sense we use in the phrase pros and cons. Further in the entry we found corroboration that pro and con is short for pro and contra “for and against.” We even noted the Latin spelling (pro et contra).

I ended our discussion by sincerely thanking the student who had brought the phrase pros and cons to our attention. What a delight to find out this information about it! At first we wondered if <pro> was a clip of either proactive or proficient, but we found out that it wasn’t a clip at all. Instead, <con> was a clip of <contra>. We now understand <pro> to mean an argument in favor of something and <con> to mean an argument against something. And yes, some may have had a sense of that before we started, but I do believe there is a difference between knowing something superficially and knowing something in a way that it didn’t before.

Within 24 hours of this discussion, three more word quandaries appeared on our Wonder Wall:

– Is influence related to influenza?

-Why is there a <u> in some spellings of <color>?

-What does “hemmed and hawed” mean?

Looks like I won’t ever have to wonder what we should talk about next! These students are in orthographic orbit!