I have been following groups on Facebook as well as people on Twitter (X) for the last few years. Specifically, I’ve been interested in spelling. How do teachers teach spelling to students? I’ve noticed several methods.

-Have students announce syllables and then spell them

-Have students announce morphemes and then spell them

-Have students announce the graphemes in each base and then the affixes as more of a unit

-Have them spell the word letter by letter

-Have them recognize some morphemes in some words, but then spell the word by announcing its syllables.

I’m wondering. Does the method even make a difference as long as they end up being able to spell the word? My experience in the classroom tells me it does.

Memorizing spelling words letter by letter was what I was taught to do and it was what my children were taught to do. It was also what I told children to do for the majority of my teaching career. It was the only way to teach spelling, or so I thought. The goal was to memorize the spelling of twenty words a week for each of the eighteen weeks of the school year. Even when students seemed successful on their Friday spelling tests, most didn’t retain the correct spelling of the words for long. Having them memorize a word letter by letter by letter only worked for a few (and by “worked” I mean that they had that word more permanently stored in their memory).

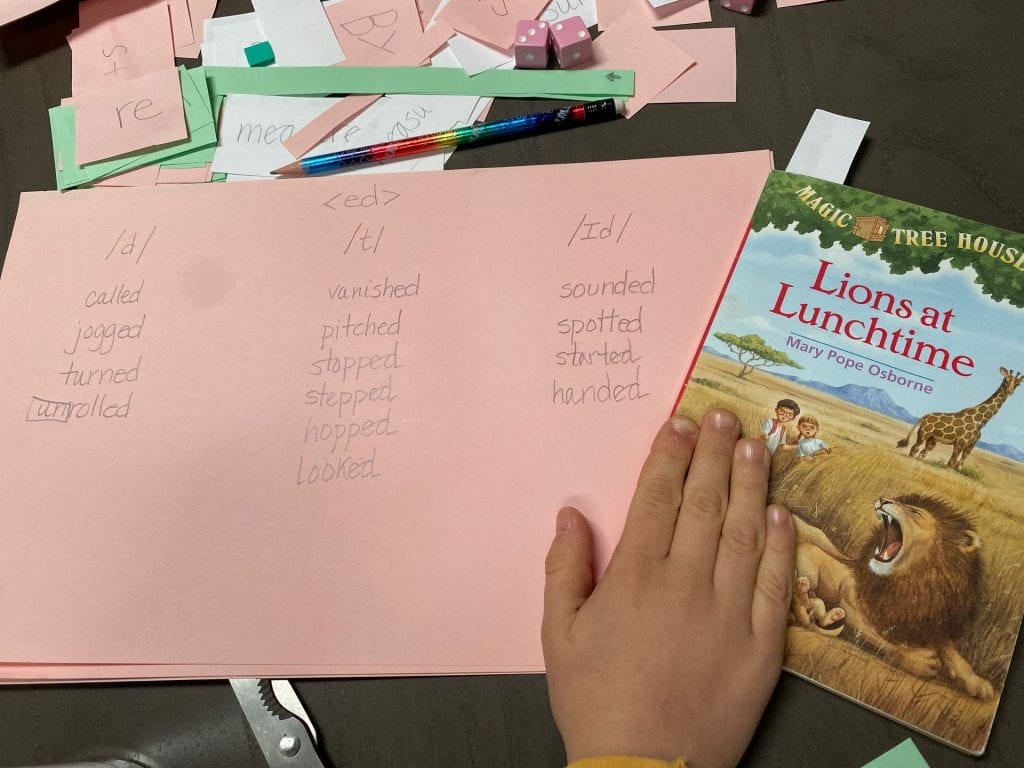

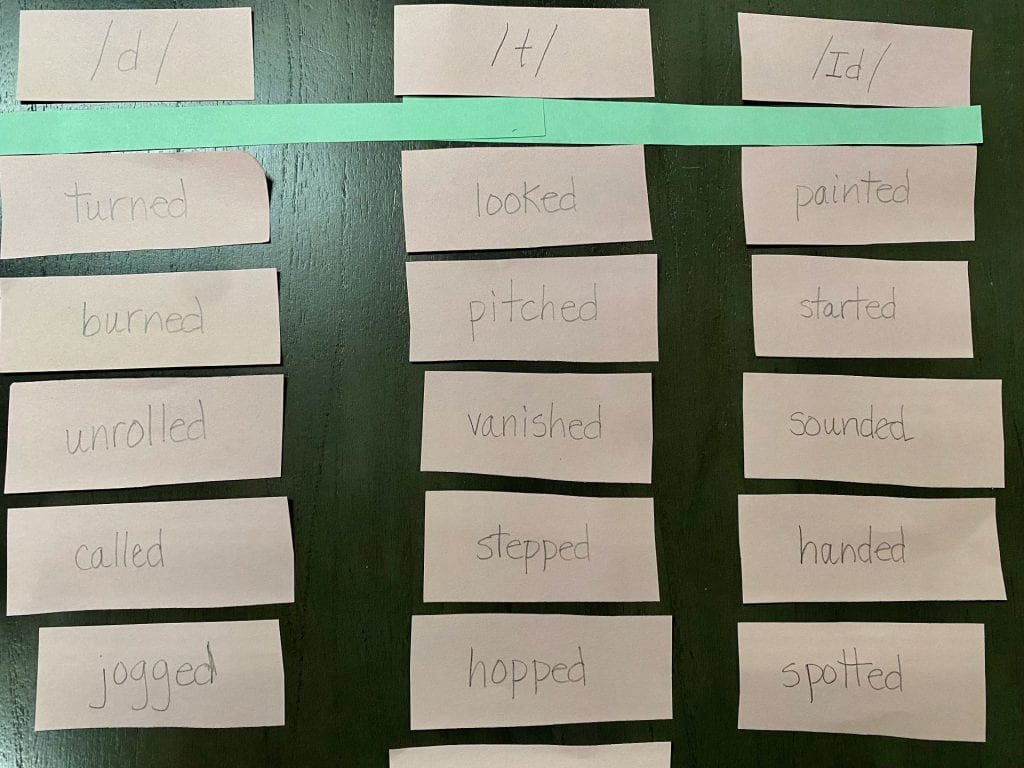

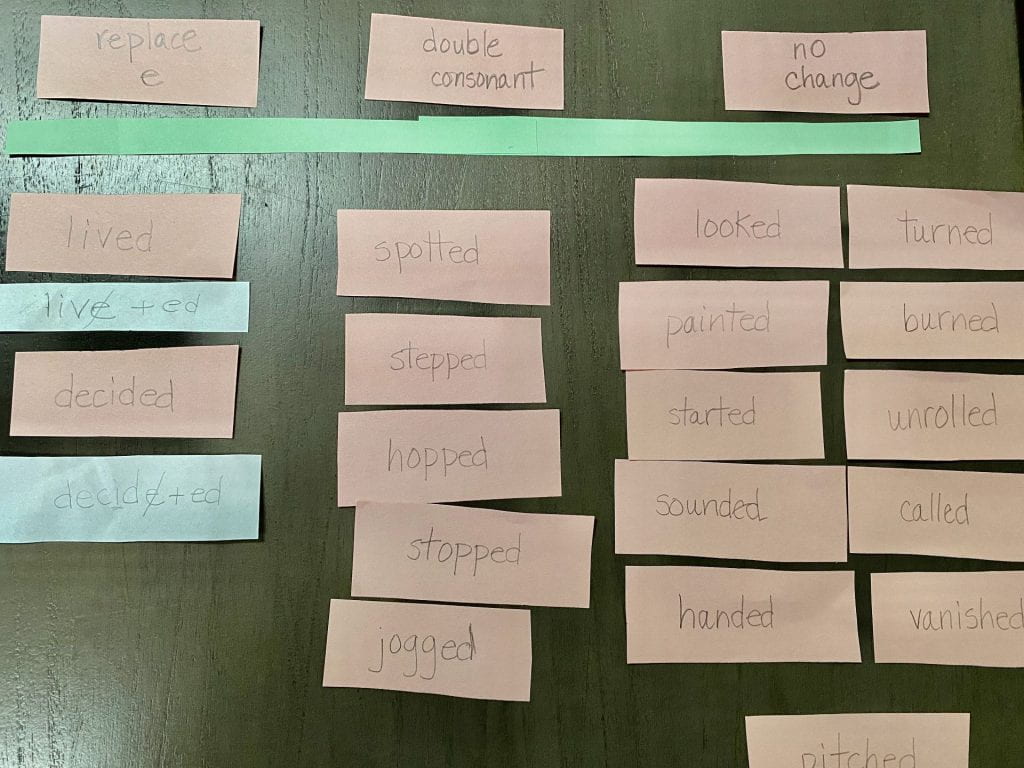

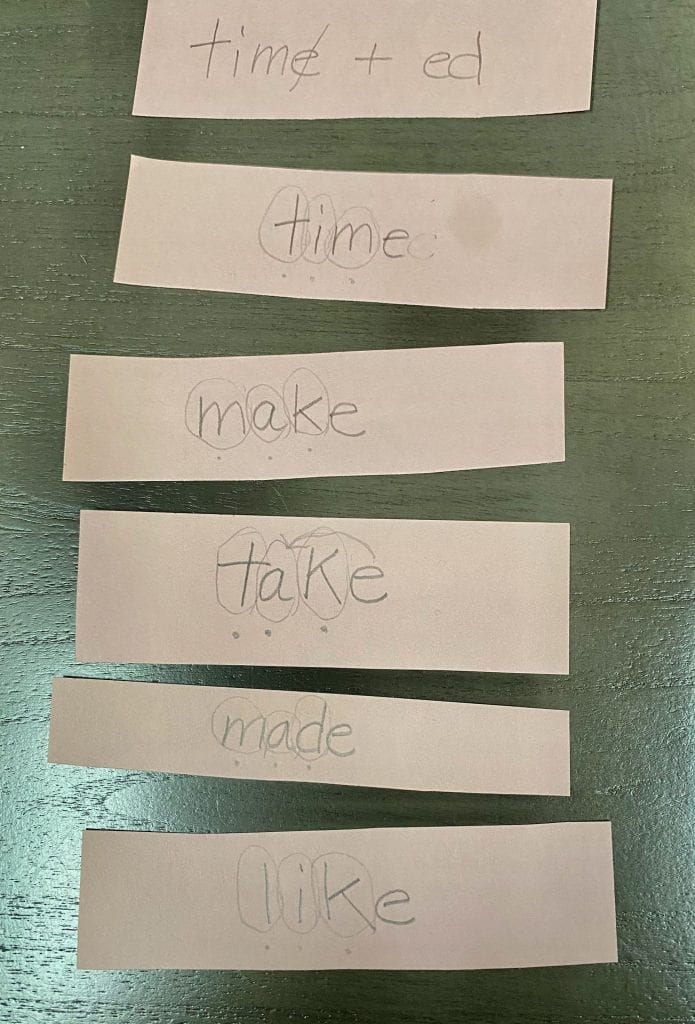

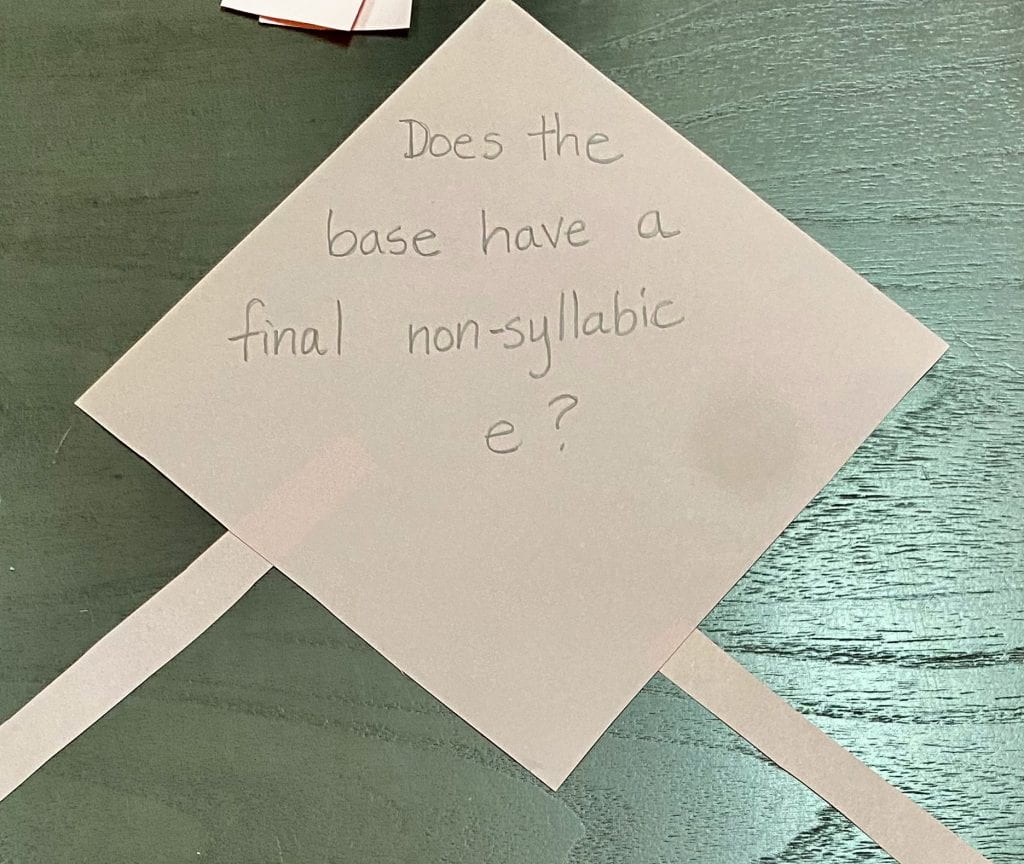

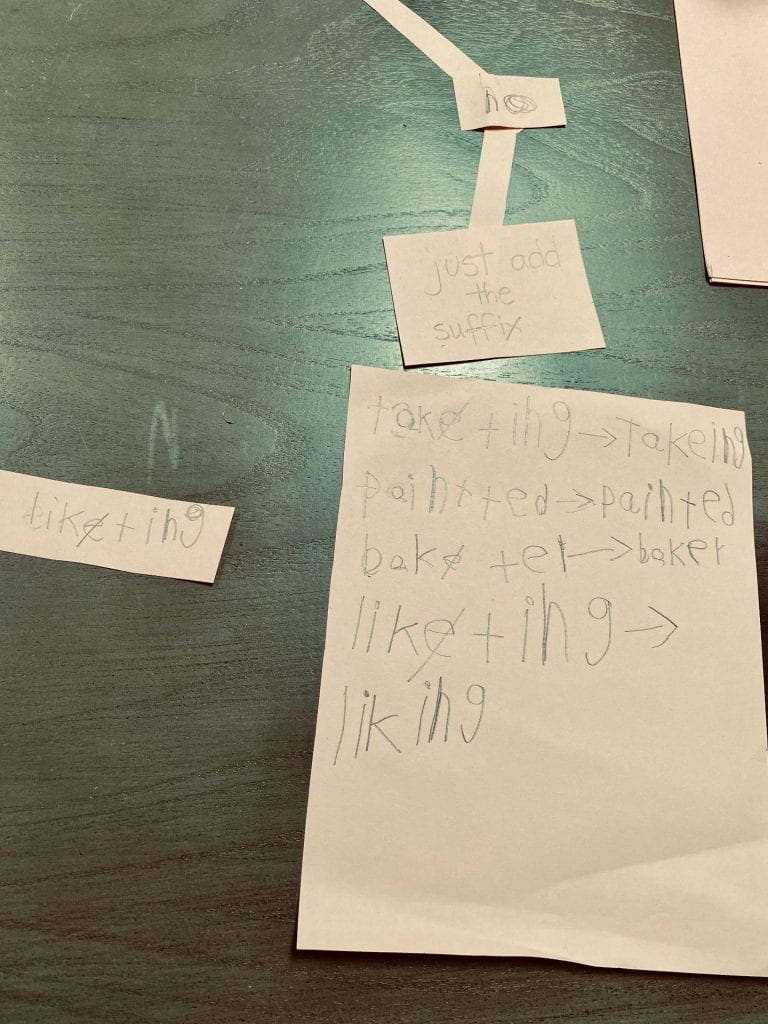

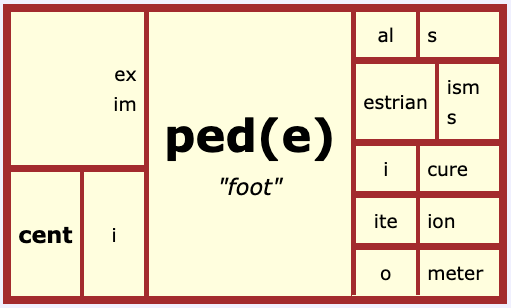

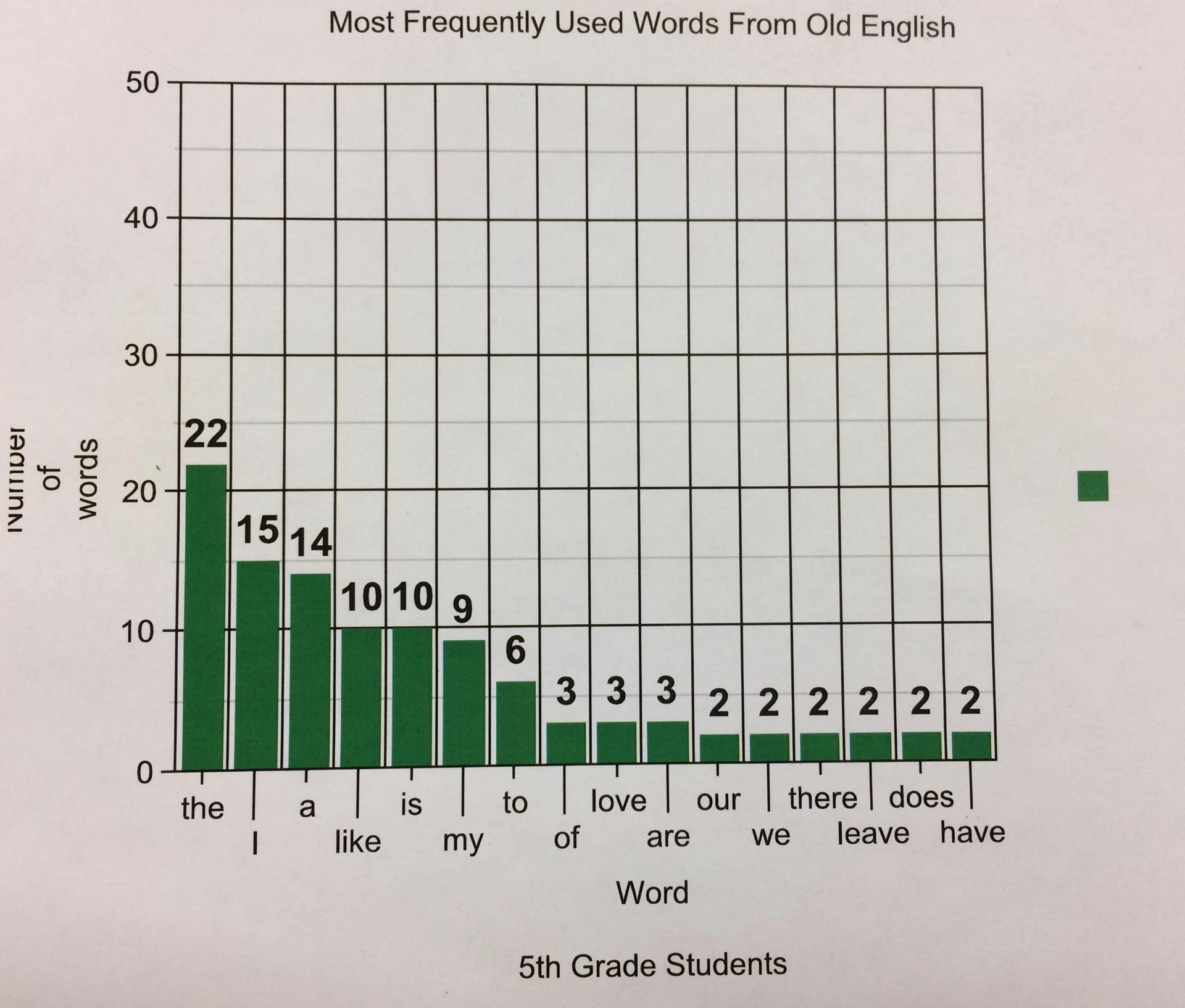

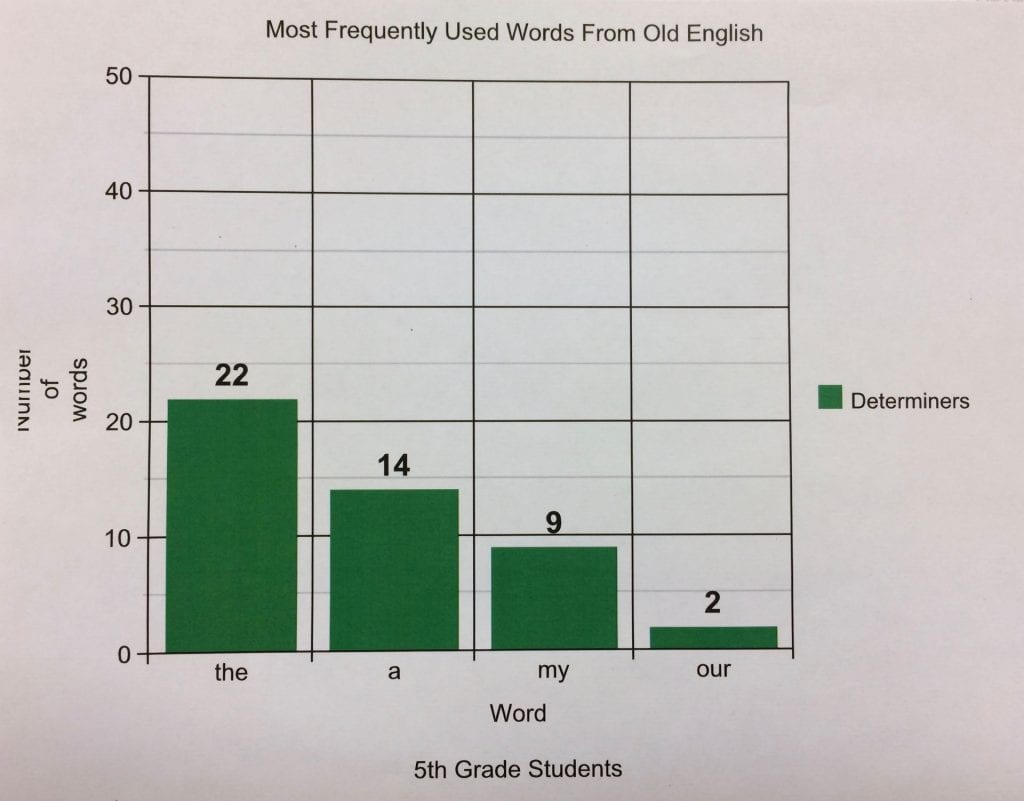

I switched away from having students memorize a spelling letter by letter when I learned about Structured Word Inquiry and began showing students that words have a morphemic structure. A word might be a free base on its own as we see in help, run, like, and stop. More often, though, a word is complex, meaning it is composed of more than one morpheme. Examples might include helpful, running, likely, and stopped. The more time my students and I spent looking at those structures, the more we began to notice that the same affixes appeared in tons of words. That may seem obvious to you, but really, it wasn’t obvious to my students. One example of that is the fact that each year I’ve had students begin fifth grade misspelling common words like ‘goes’. The only spelling strategy they knew to use was to sound out the word. That is why I was seeing ‘goes’ spelled as *gows, *go’s, *gose, and *gous. At some level, I’m sure the students knew that ‘goes’ was related in meaning to ‘go’. But I don’t think they were explicitly shown the spelling relationship: <go>, <go + es>, <go + ne>, <go + ing>. If they had been, they wouldn’t have thought that the word was spelled with a <go> base and a *<ws> suffix, would they?

My school district is in its second year with UFLI. It will take a while to see if that makes a difference in their understanding of spelling as the students reach the upper elementary grades. What I saw in fifth grade was students who either thought spelling was dumb or students who loved spelling. Can you guess which of those two groups was great at rote memorization and which wasn’t? It wasn’t really about understanding spelling at all. The curriculum we used was vague – talked about long and short vowel patterns but never addressed “why.” Why do we use an <ea> instead of <ee>? As a result, none of the students knew why a word had a particular spelling. They memorized the spelling by announcing it and then they took a shot at spelling out those sounds. As they grew older, they realized that not all of the words on their list were words they use frequently or even know. As a result, they had to also memorize what the word meant. Let me share a personal story here.

Reading didn’t come easily for my son. (Oh, if I knew then what I know now!) He could do it, but it took so much effort that it wasn’t enjoyable – at all. His writing contained a variety of spelling errors, but could still be read and understood. One time, when he was in high school, he asked me to help him study for a vocabulary test. Instead of reading the definition the teacher had given the students, I reworded it to make sure he had the sense and meaning of the word. He was livid! “Mom! I don’t need to really know that! If I want to pass, I just need to know the first three words of the definition and the first four letters of the word they go with!” He grabbed his papers and said, “I’ll study by myself.” Wow. What an eye-opener! And just in case you’re wondering, he passed the test–without understanding or being able to use any of the vocabulary words he was tested on. Poor teaching? Yes, I’d say so. Kids will figure out how to get around any task that is hard and confusing.

This story reminds me that when we make spelling a task to be done separate of meaning, we make extra work for children. Having students spell syllable by syllable, when syllables are only about pronunciation, is separating the spelling from the meaning. Another step must be added to the process–that of attaching meaning to the word. If memorizing the spelling was a difficult task for the student, memorizing a meaning to attach to it will be just as difficult. It’s like playing a matching game when you don’t know what it is about one that makes it a match for the other. My guess is that my son hasn’t been the only student who has given up on learning and instead resorted to just focusing on passing the test.

A second problem I see regarding teaching students to spell words by announcing their syllables, is that students now need to be taught percentages. 70% of the time this pronunciation is spelled this way. If that doesn’t work, try this spelling. It works 15% of the time. If that doesn’t work, try this spelling. How is that method not adding cognitive overload? And does it teach students to see connections in spelling and meaning between words like one, once, alone, atone, and only? My guess is that the students might see a meaning connection between words that share pronunciation (like one and once), but they won’t include alone, atone, and only in that same meaning connection because they are taught that pronunciation is the most important thing about a word. They haven’t learned to notice spelling similarities when pronunciation tells them the words aren’t related.

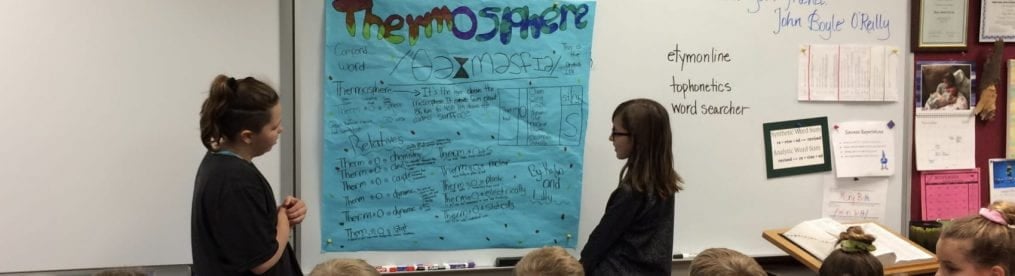

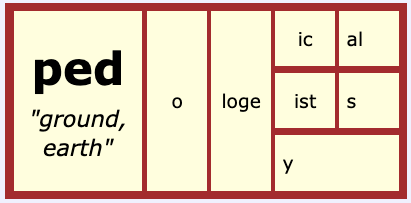

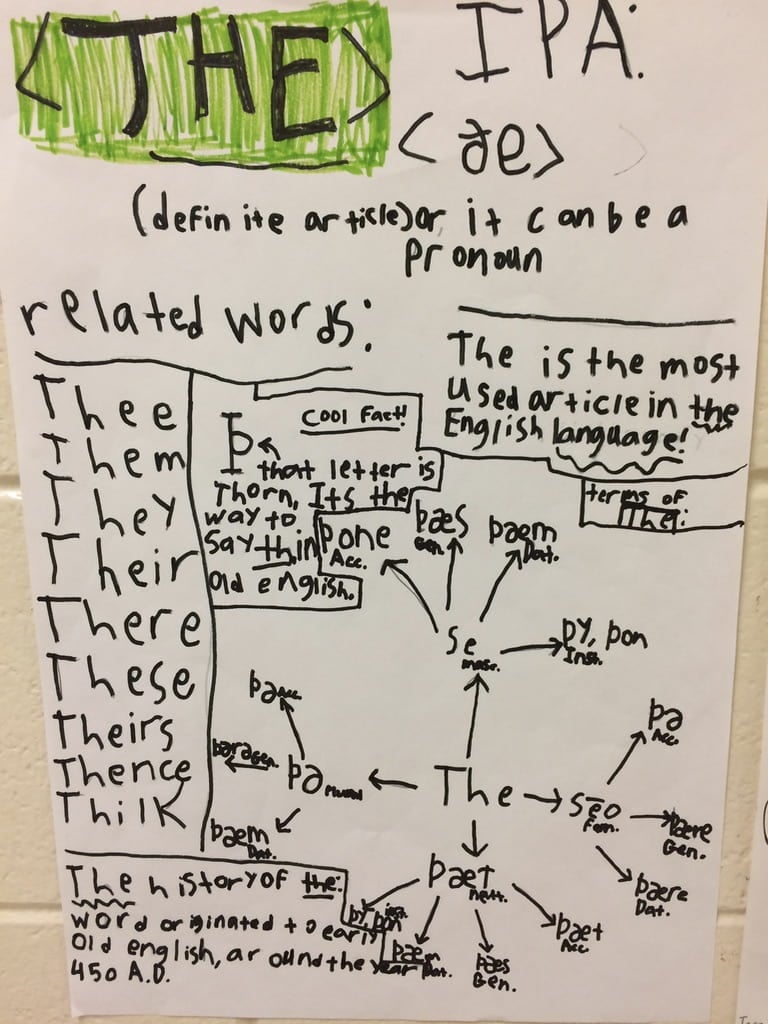

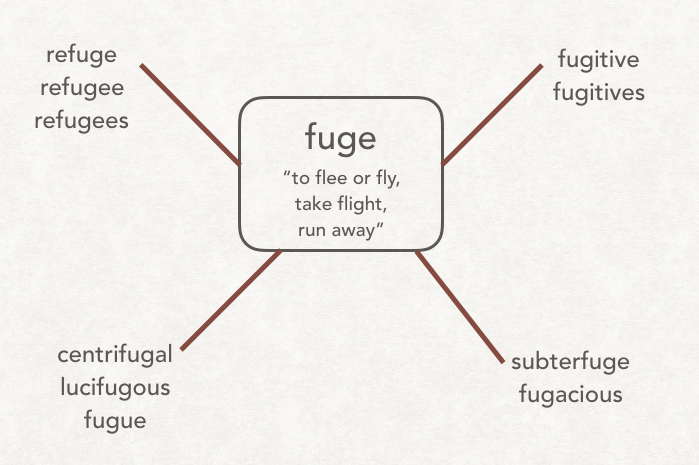

When we teach students the morphemic structure of words, we teach meaning and spelling at the same time. We connect the two right from the start. When we investigate the word in the context of its larger family (including other words that share the word’s root), students learn not only about that one word and its meaning, they learn many of the features of our language. They begin to see suffixing conventions as something applied predictably and logically. They begin to realize that the word’s spelling is better understood –more memorable–when we include its etymology. Instead of asking, “How do you know when to use <ea> or <ee> in a word?”, students instead wonder, “Why is this word spelled with <ea>?” In other words, instead of questions that will yield answers accompanied by lots of exceptions, students focus on one word family at a time and begin to see patterns across that word family as well as across others. They begin to see that by examining a word’s morphemic structure, its etymology, and its grapheme to phoneme correspondences, they have a more complete picture of what it is possible to understand about a word–any word.

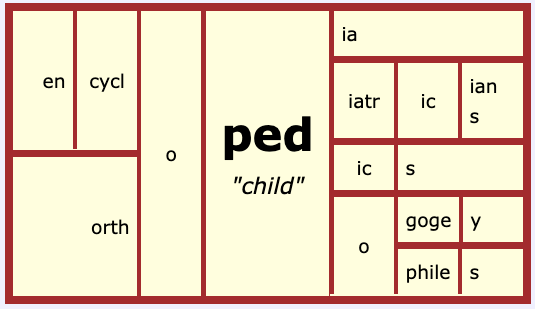

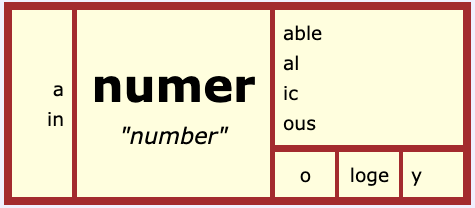

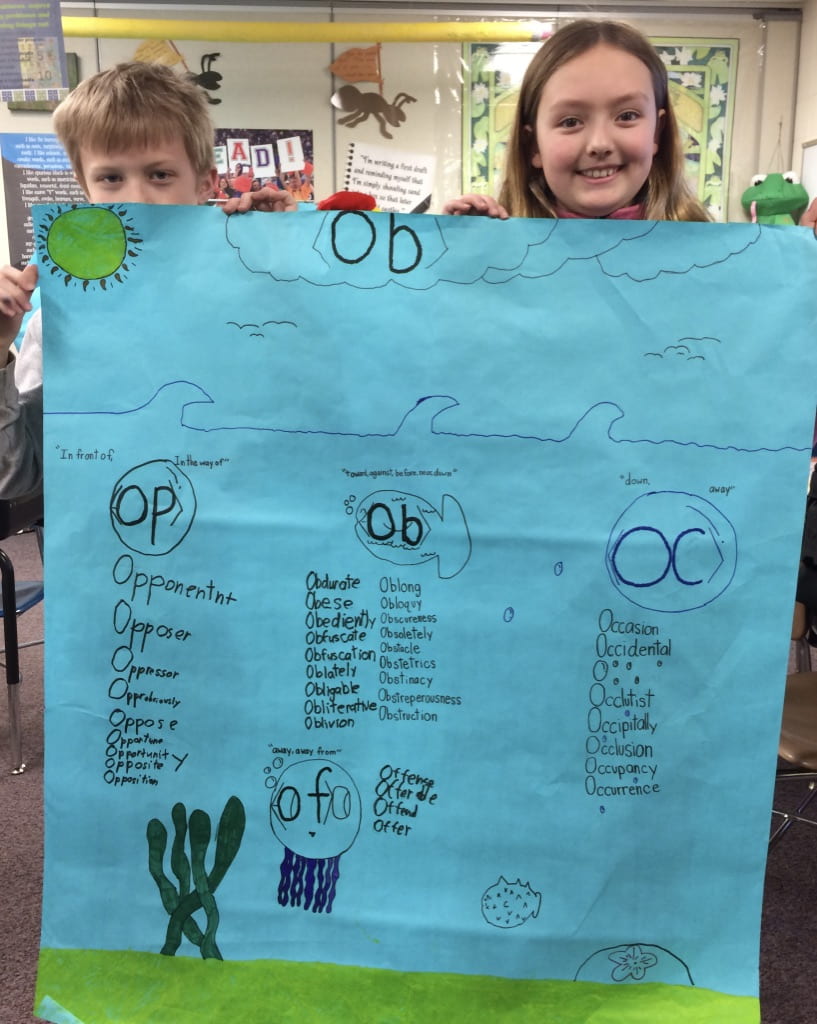

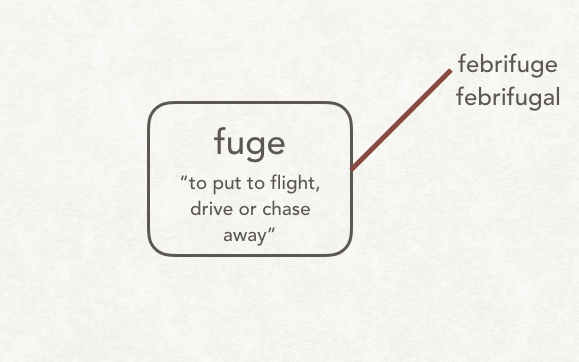

By hypothesizing word sums and then seeking the evidence to support or falsify those hypotheses, students gain awareness of the morphemes we see in numerous word families. A larger number of affixes become familiar to students in a shorter amount of time when compared to the method of teaching a short list of prefixes and suffixes to students over the course of a specific school year. Why ask the student to wait three or more years to be able to take a close look at affixes the student is reading now? I’m not suggesting we give the students a list of every possible affix all at once either. I’m suggesting that when we look closer at words the students are curious about, we show them the structure–even if there are affixes we haven’t talked about yet. The overall message to students should always be that words are made of one or more morphemes. The more word families the students explore, and the more often they ask themselves where else they’ve seen an individual morpheme, the more morphemes they will recognize with automaticity. Recognizing morphemes in unfamiliar words gives students a distinct advantage when reading. My students have told me this time and time again.

“Mrs. Steven, there was a word on the Star test that I didn’t know, but I used what you’ve been teaching us and figured out part of its meaning! It really helped!”

“I was watching the news last night and they used a word I hadn’t heard before. When I thought about it, I recognized part of it and it made sense when I connected it to what the news guy was talking about!”

“How do you say this word? I figured out what it meant when I was reading last night, but wasn’t sure how it would be said.”

There are plenty of teachers who believe that controlling the number of affixes and bases taught to a student is optimal. They believe that explicitly teaching affixes and bases as suggested in a published program is preferable to teaching students to conduct investigations for themselves. They fear that without explicit instruction of a list, not all students in a group will know the same affixes. That while using a list, the teacher can account for which of those affixes the students know. They also worry that asking a student to know too many affixes and bases is cognitive overload. If those affixes and bases are taught in isolation, outside the context of an actual word, I would agree. What eases cognitive load is connecting the once isolated morphemes to other morphemes through meaning and spelling.

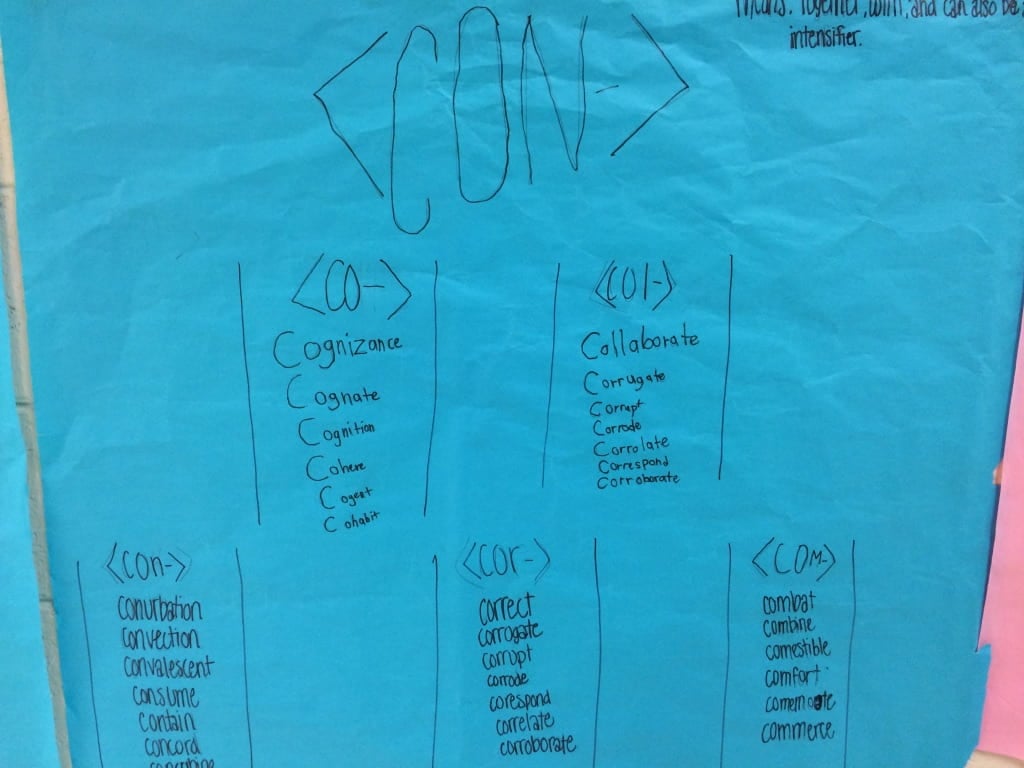

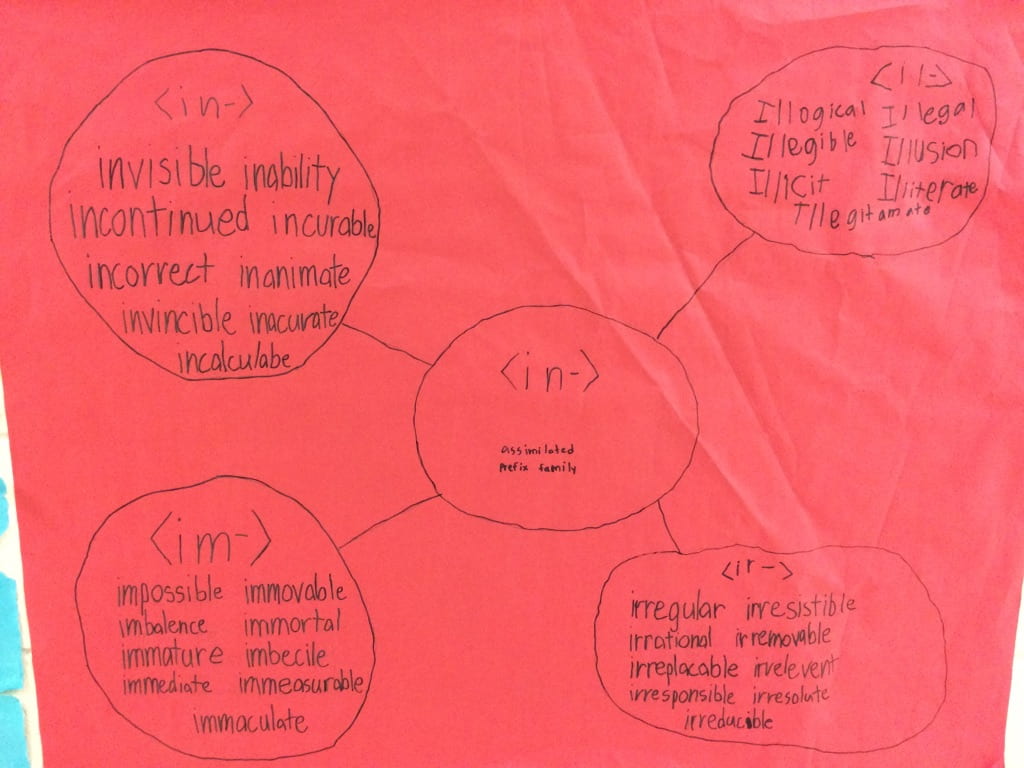

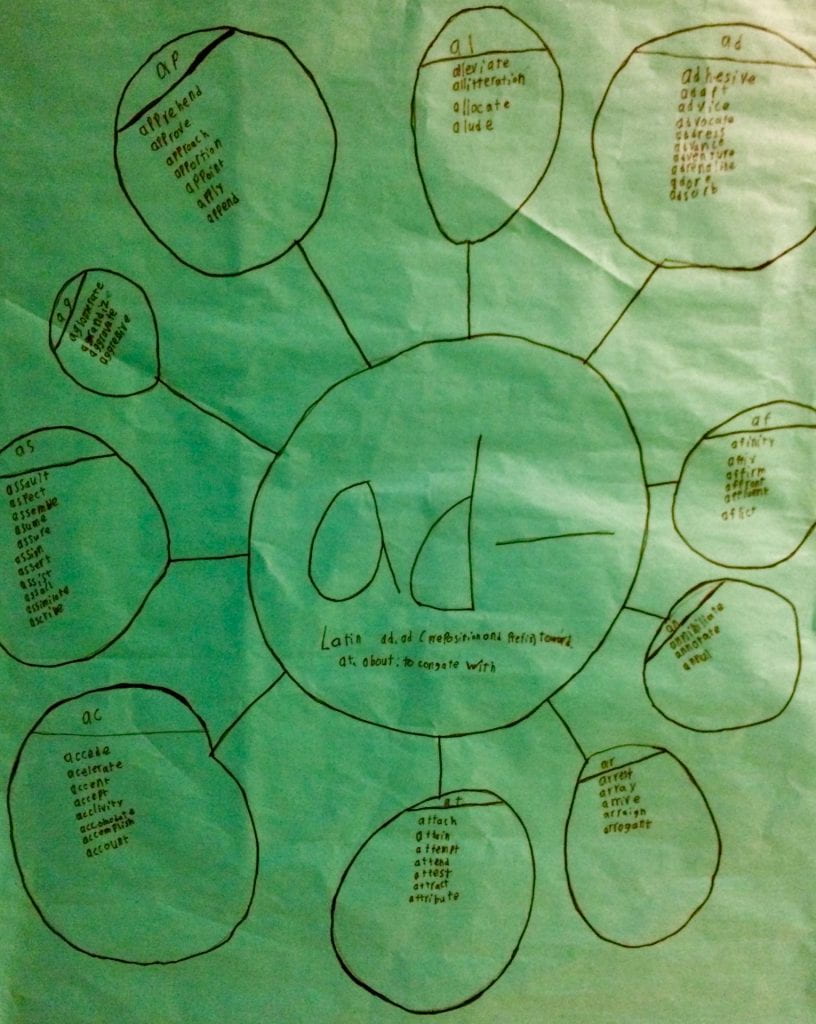

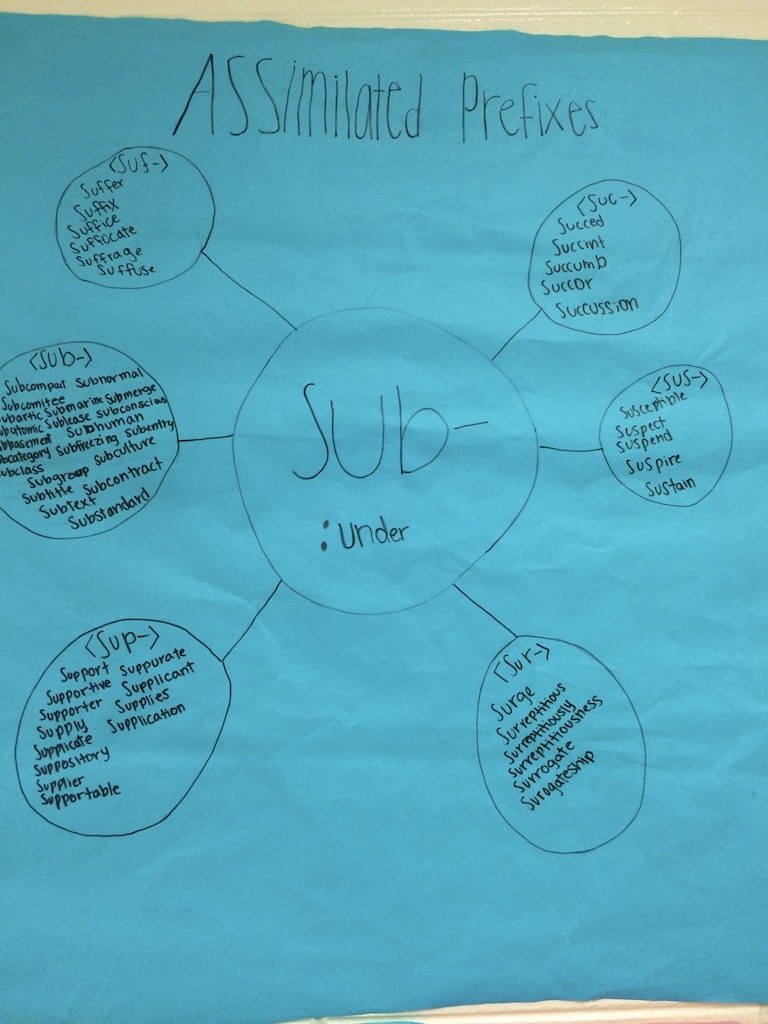

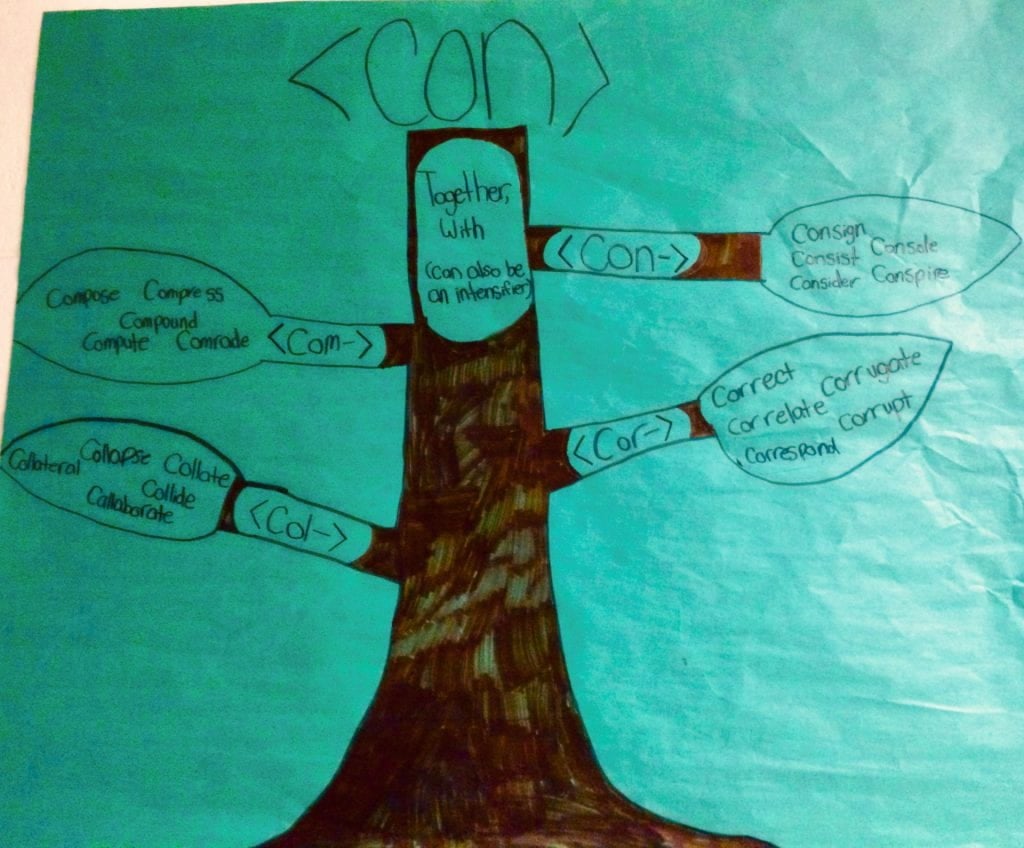

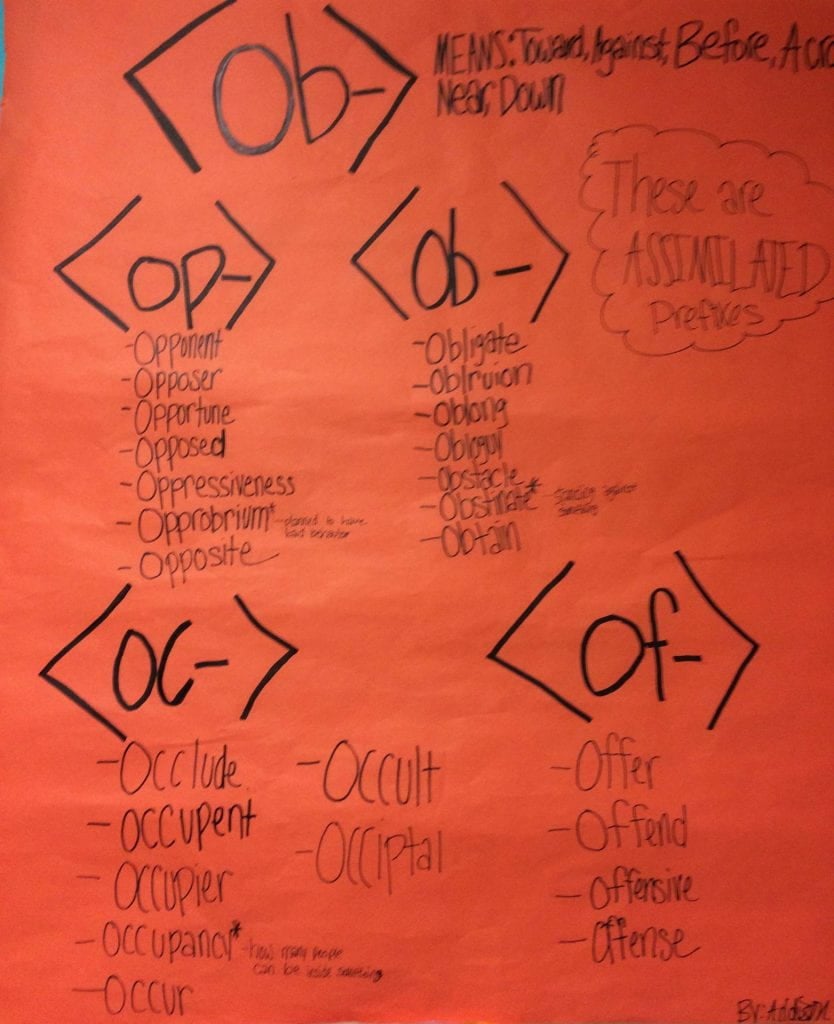

One problem of teaching from a list is the way assimilated prefixes are taught. In many programs, students are taught <con-> and <com-> at the same time. But why not also teach <cor->, <col->, and <co->? They are either on the schedule for some other year or not on the list at all. All five of those are alternate spellings for the <con-> prefix. It most often brings a sense of “together, with”. It doesn’t make sense to leave them out when students are reading words that include them (like corrode, collide, and coauthor). The teacher is helping students see the structure in ‘conduct’, <con + duct –>conduct> and its literal meaning “lead together”, but not showing the students the same prefix in ‘collide’. <col + lide –> collide> and its literal meaning “strike together”. Doesn’t make sense to me.

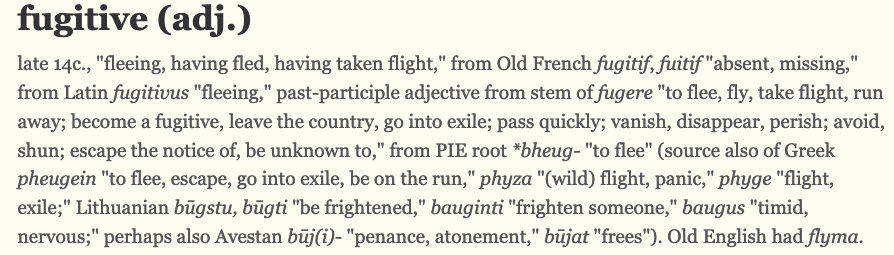

Students are also being taught that prefixes mean the same thing in every word they are a part of. Not true. Let’s look at <re->. Most programs teach that it means “again”. And in many words it does (rerun, reuse, redo). But how confusing is it when a student looks at ‘reduce’? It doesn’t mean do something again,” it means make something smaller, literally “lead back.” In this word, <re-> brings a sense of “back.” Even more confusing is a word like ‘refine’. Something isn’t being made fine again, it is intensely becoming fine. In this word, <re-> is an intensifier. My students and I have found that it is best to check with an etymological resource when wanting to have the best understanding. Many prefixes have more than one sense they can bring to a word. The only way to know for sure what meaning the prefix carries is to look at a resource. Programs that teach <re-> means “again,” will give a list of words to practice in which it does bring that sense. The confusion sets in when neither the teacher nor the program is around and the student encounters a word that doesn’t fit what they were told. That’s why teaching students to use resources for themselves is so helpful.

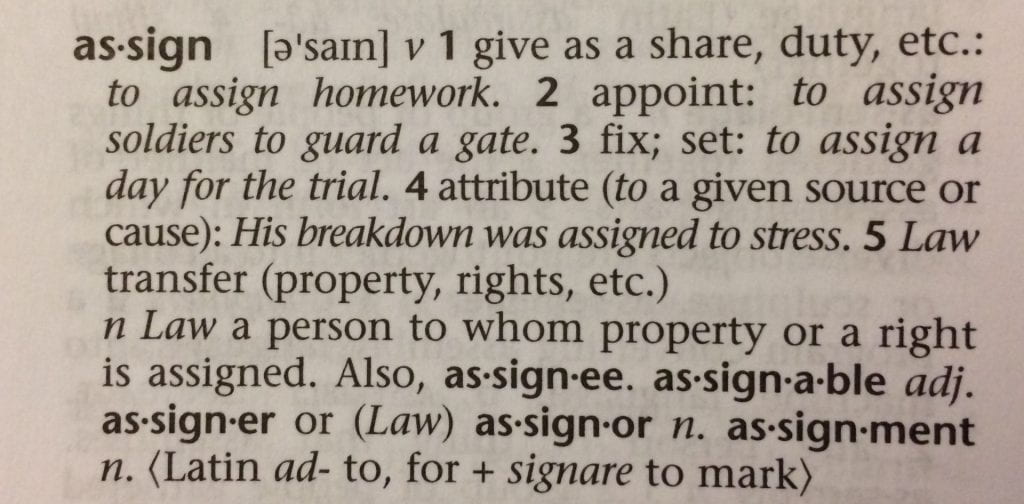

When a teacher gives a student a list of prefixes, bases, and suffixes to know and then includes a short list of words that include those morphemes, they are, in effect, telling the students what to see. The students will probably be successful in spotting those morphemes in those words for a long time. But what about spotting those morphemes in unfamiliar words? Will they notice those same morphemes then? Or will the environment (surrounding morphemes or pronunciation of them) obscure their presence? When my students and I hypothesize a word sum and then check with an etymological resource like Etymonline, our next step is always to recognize where we have seen those morphemes. What other words have the same <con> that we see in ‘conjunction’? (conform, confiscate, construction). Every time we “prove” a prefix is a prefix, we do so by coming up with three or so words that clearly have that same prefix in their structure. If the students can’t think of three examples offhand, we look together in dictionaries or on Word Searcher. In this way, they become familiar with how to use research toolsand in doing so, gain a level of independence in their morpheme searches. The students become noticers of words in all kinds of situations, and they do that without me needing to be there to show them what to look for.

I have also seen some teachers consistently show students the syllabic division of the word and only inconsistently the morphemic structure. Perhaps this is because their own understanding of bases is limited. They show the structure of words that have free bases (<help + ful + ness>; <move + ment>; <busy + est>), but are less inclined to show their students the structure of words that have bound bases (<de + duce/ + ed>; <mote/ + ive/ + ate/ + ion>;<aut + o + bi + o + graph + y>). Doesn’t this send mixed messages to the students? If you can identify the morphemes and their meaning in one word, why can’t you do it in all words? We’re back to promoting the idea that English spelling is inconsistent and unpredictable. When my students and I have been unsure of a specific word sum analysis, we have always looked to the evidence we could find in our resources. If we couldn’t find evidence to support our hypothesis, we backed up and instead of thinking we had two morphemes, we wrote them as one, acknowledging our suspicions about a further analysis and leaving that door open should further evidence become available. This is different than saying our analysis is either right or wrong. What better lesson can we be teaching our students than to rely on evidence?

If morphemic structure isn’t being taught consistently, they are not seeing the advantage there is in identifying a word’s morphemes – especially when it comes to spelling. The teacher in this instance goes back to announcing syllables and hoping the student has seen the word often enough to remember how the phonemes are spelled. The only thing the students have to go on is the pronunciation given by the teacher. Syllables, after all, aren’t like morphemes. They aren’t consistent from one word to another. Other than a few exceptions, we don’t see the same syllables over and over. On the other hand, once a student is familiar with a group of prefixes, suffixes, and bases, they don’t have to think about how to spell them. They only need to focus on the morpheme that is new to them. Depending on the word, it could be more work figuring out the spelling of its syllables than spelling out its familiar morphemes.