I ran across a fascinating article recently called “Anumeric People: What Happens When a Language Has No Words for Numbers?” While I immediately noticed the word ‘anumeric’ in the title, I set it aside while I read the article and imagined a life without words for numbers. What are the advantages/disadvantages? It’s quite likely that there are people in remote areas of the world whose lives don’t revolve around clocks and other numbered things. But is the ability to distinguish by number the difference between 3 and 6 items crucial to one’s existence? Obviously not, for the people who only have words to name “some,” have lived for generations. The interesting focus in this article is “how the invention of numbers reshaped the human experience.” The article is not particularly long, but certainly gave me something to think about!

Now. Back to the word ‘anumeric.’

Right away I connected it to the following.

numeric

numeral

numerous

innumerable

numerology

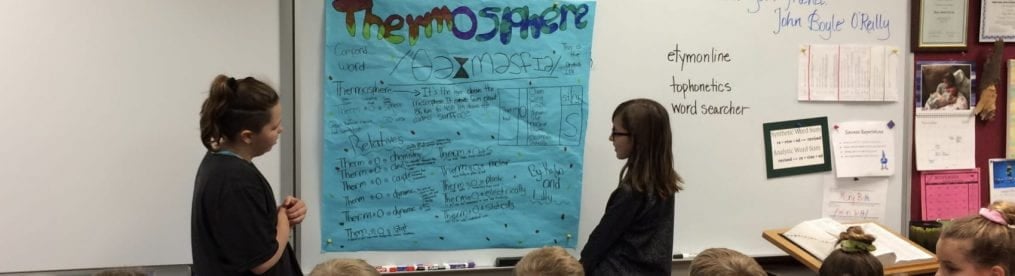

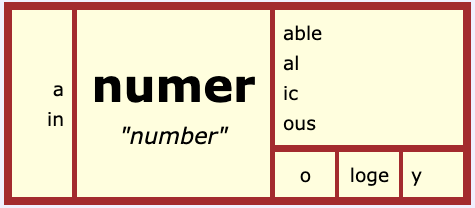

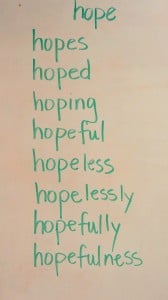

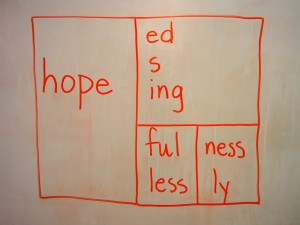

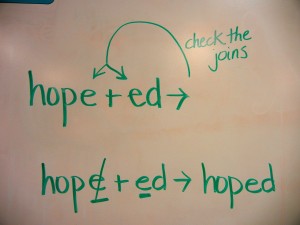

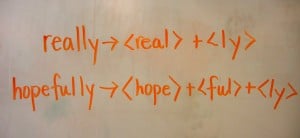

If you compare the spelling of these words, you’ll notice (as my students would) that they each have <numer> in common. If given the opportunity to write a word sum hypothesis for ‘numeric’, I might see students write both <numer + ic> and <num + er + ic>. They are both logical. The first includes the letter string that is consistent among the words and might be the base. The second includes prior knowledge of <er> being the suffix in baker, teacher, and colder.

Once we have discussed the hypotheses and the fact that both are based on what we already know to be true about word construction, it is time to find evidence that will support one more than the other. If I look in either Etymonline, Chamber’s Dictionary of Etymology, or the Oxford English Dictionary, I find that all the words on our list derive from Latin numerus “a number.” Once the Latin suffix <us> is removed, we see the Latin stem that came into English as the base <numer>. This evidence shows that the <er> was part of the word’s spelling in Latin and is part of the base in English. I like to compare this situation to the <ing> in ‘bring.’ We know there to be an <ing> suffix, but that doesn’t mean that every time we see that letter string we are looking at a suffix. It’s logical to wonder about it, and scholarly to check with a reference!

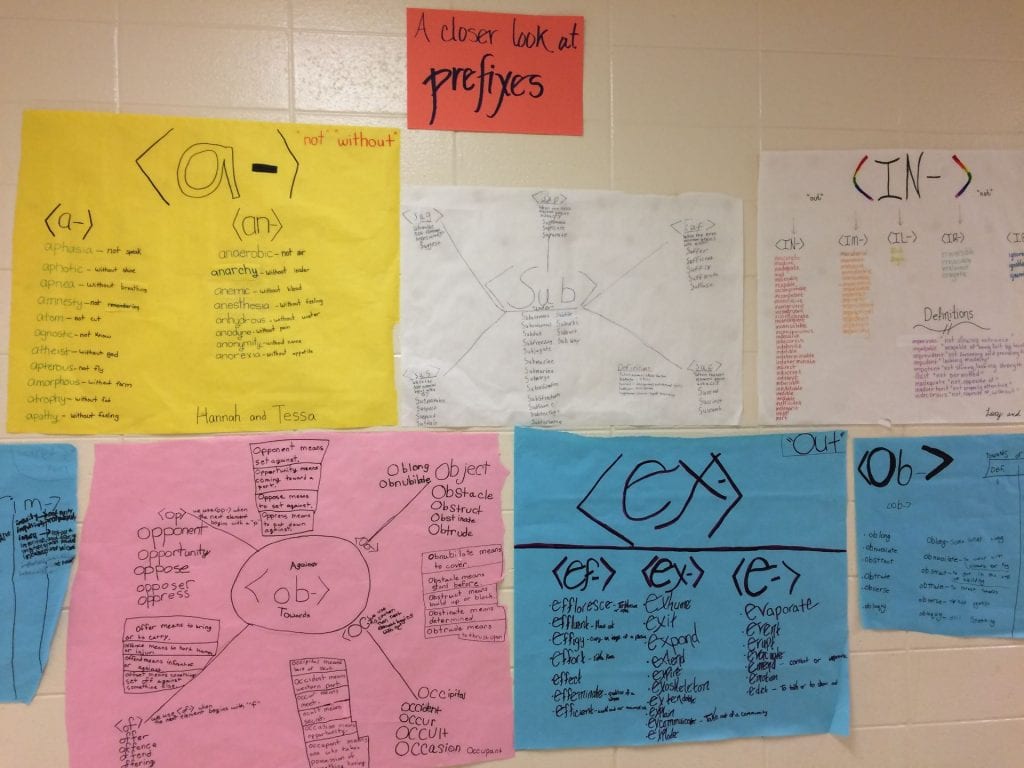

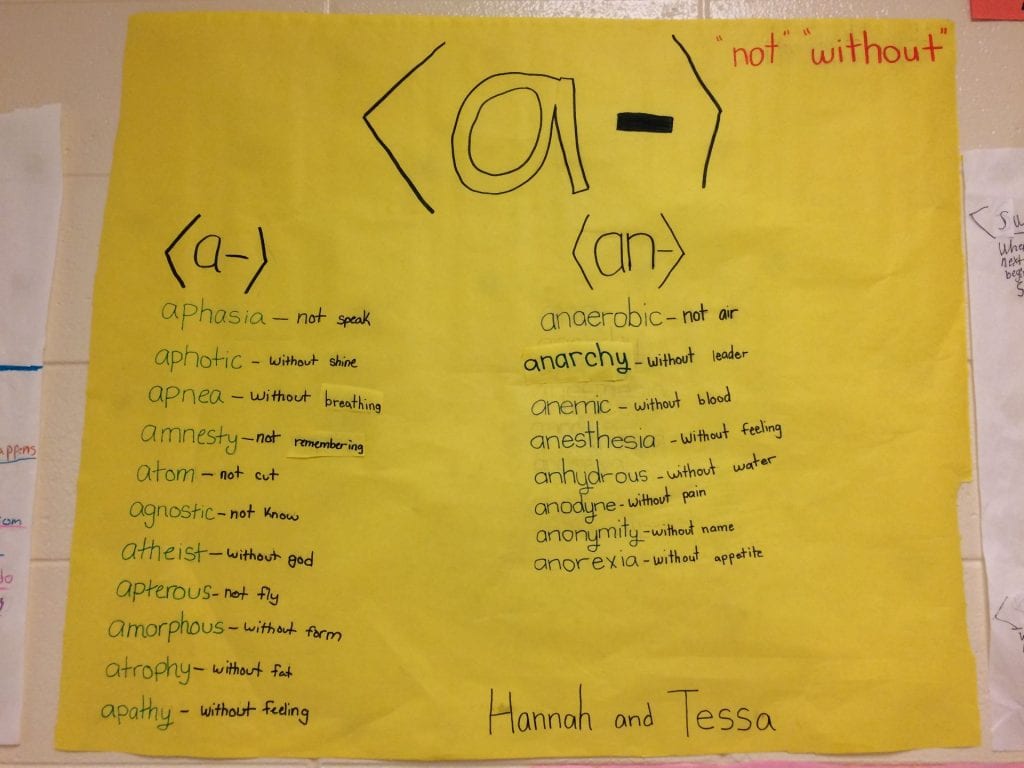

Once I had looked closer at the base of ‘anumeric,’ I thought more about the prefix <a>. Thinking about its use in the article where I found it, it obviously has a negativizing sense. It has a similar use in the following.

apnea – without breathing

amnesia – not remembering

atheist – without a god

apathy – without feeling or emotion

atypical – not typical

aphotic – without light

The prefix <a> that incorporates a sense of “not, without” is sometimes spelled <an>. According to Etymonline, it is “a fuller form of the one represented in English by <a>.” You may recognize the <an> prefix in the following.

anarchy – without a ruler

anonymous – without a name

anomaly – not the same

anesthesia – without feeling

anhydrous – without water

So does this mean that every time we see a word with an <a> or <an> prefix that it contributes a sense of “not, without?” No. No it doesn’t. There are a number of words like asleep, awash, aside, and aflame that originated in Old English and in which the prefix <a-> contributes a sense of “on, in, into.” That <a> prefix can also be an intensifying prefix as it is in ashamed. An intensifying prefix is one that doesn’t contribute a separate sense to the base, but instead intensifies the action of the base. (More about intensifying prefixes to come.)

An unexpected sense

As I began a deeper dive, looking at words with an <a> prefix, I came across afraid, award, and astonish. The word ‘afraid’ was derived from Anglo-French (afrayer) and further back from Old French which influenced the spelling (affrai, effrei, esfrei) and further back from esfreer “to worry, concern.” The first part of this word is actually derived from Old French es-; Latin <ex-> prefix “out” and the second part is from Vulgar Latin *exfridare “to take out of peace.” Please note that the asterisk in this ancestor means that the spelling is unattested. This spelling is thought to be a likely spelling by those who study languages. Beyond that, just think about the denotation of this word! To be afraid is to have been taken out of peace! Don’t you love it?

Looking at ‘award,’ this is another word that was derived from Old French. It is from Old French (awarder) and further back from Old North French (eswarder). Do you notice the initial <es> spelling? To award something to someone is to give one’s opinion after careful consideration. As with ‘afraid,’ the first part is actually from the Latin <ex-> prefix “out” and the second part is from Germanic warder “to watch.” So the person choosing who will receive an award is the one who watches out for which person will be deemed most worthy!

That brings us to the word ‘astonish.’ This word, too, was influenced by its use in Old French. It is from Old French estoner “to stun, daze, deafen, astound.” If you noticed the ‘es’ in the Old French word estoner, you may be expecting that the first part of this word is from Latin <ex-> “out,” and you’d be right! The base is from Latin tonare “to thunder.” If something astonishes you, it leaves you a bit stunned or dazed, as if you were shook by thunder!

So the question with afraid, award, and astonish is whether or not they have an <a> prefix. The etymology clearly reveals that the prefix sense here is from <ex> even though we see an <a> prefix. The story of how the <ex> prefix came to be spelled as <a> can be found in the influence of Anglo-French and Old French spellings! So here we have evidence of words with an <a> prefix that represents Latin <ex>.

Assimilated forms of other prefixes

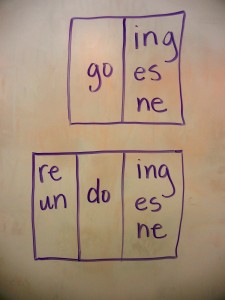

The prefix <an> can also be an assimilated form of the prefix <ad> “to” as it is in announce, annul, and annexation. You’ll notice that the <ad> assimilates to <an> when the next element in the word begins with an ‘n.’ The <ad> prefix can reduce to <a> in words like ascend, ascribe, avenue, and avenge.

In the word ‘avert,’ the <a> is a reduced form of the <ab> prefix “off, away from.”

If you’re wondering, “How will I know which prefix it is or which sense it brings to the word I’m investigating?” Fear not! A quick check with a reliable source like Etymonline will clear up which <an> you are looking at as well as which sense it brings to the base or stem!

What about other prefixes? Are they all like this?

Once I got thinking about <a> and <an> as a prefix, about all the different ways it can contribute sense to a word, I thought about all the other prefixes that I have been similarly surprised at. You see, prior to SWI, my understanding was that prefixes contribute a consistent meaning to each word they are attached to. For instance, in books that I was using to understand prefixes, suffixes, and “root words,” the prefix <re> was listed as meaning “again.” The examples given were similar to remarry, reuse, and resupply. Every prefix that was mentioned had a specific definition. Examples of some of those are below.

de – down

dis – away

ex – out

in – not, without

pre – before

un – not

con – with

I bet you’ve seen lists like this. Taking a close look at the English spelling system by incorporating Structured Word Inquiry into my teaching and learning has made me realize so much! For instance, the way in which a prefix steers the meaning of the base isn’t as “set in stone’ as we have been led to think. We’ve already had a glimpse of that with our look at the <a> prefix!

Recently the International Dyslexia Association presented a live Facebook chat featuring Sue Scibetta Hegland, who spoke on the topic of incorporating morphology in spelling instruction. The presentation was recorded and you can watch it below. In this talk, Sue uses the prefix <dis> to address the very point I am making in this post. I encourage you to watch it. Besides her point about prefixes, she makes many many others that are so eye-opening! In the paragraphs following the video, I have elaborated on the point she made with <dis>.

If you think about words in which you’ve seen a <dis-> prefix, you might think of words like disapprove, disappear, and disable. In all three of these words, the prefix brings a sense of “opposite of.” If you disapprove of something, that is the opposite of approving. When something disappears, it does the opposite of appearing. When a machine is disabled, it is the opposite of when it is able to do its intended job.

In the words distract, disrupt, and dismiss, the <dis-> prefix contributes a sense of “away” to the denotation of the base. In all three of these examples, the prefix is paired with a bound base. Looking closer at ‘distract,’ the base <tract> is from Latin trahere “to draw.” When someone is distracted, their attention has been drawn away from where it was. Looking closer at ‘disrupt,’ the base <rupt> is from Latin rumpere “to break.” When a meeting is disrupted, everyone’s attention is broken away from what it had been focused on. Looking closer at ‘dismiss,’ the base <miss> is from Latin mittere “to send, let go.” When you dismiss your students, you send them away!

A third sense that the <dis-> prefix might bring to a base or stem is “not.” This is the case in the words displease, dislike, and dishonest. When you are displeased, you are not pleased, When you dislike something, you do not like it. When you are dishonest, you are not being honest.

There are other senses as well. In the word ‘distribute,’ the base is from Latin tribuere “to pay, assign, grant.” The prefix <dis-> contributes a sense of “individually.” When you distribute materials, you are assigning those materials to each individual in the group. In the word ‘distort,’ the base is from Latin torquere “to twist.” The prefix <dis-> contributes a sense of “completely.” When something is distorted, it is completely twisted (whether physically or metaphorically). In the word ‘dissension,’ the base is from Latin sentire “to feel, think.” the prefix <dis-> contributes a sense of “differently.” When there is dissension within a group of people, they no longer are in agreement. Some or all think differently than the leader of that group.

Intensifying prefixes

I spoke earlier about prefixes that act as intensifiers. The example I gave was ashamed. In ‘ashamed,’ the state of feeling shame is intensified. There are others, of course. Once you begin finding them for yourself, you’ll experience a new kind of fun! Until then, here are a few I’ve discovered.

Let’s compare the words ‘reunion’ and ‘refine.’ A reunion happens when people are coming back together again to become one group with something in common. The main sense and meaning of that word, “the act of joining one thing to another,” has been consistent since it was first attested in the early 15c. The prefix ‘re’ adds that the act of joining one thing to another is happening again. These people have come together before and now they are coming together again. According to Etymonline, the word ‘refine’ was first used with a reference to metals (1580) and later to manners (1590). It has to do with reducing something to its purest form (or as close to it as one can get). The main sense and meaning of that word is “make fine.” In this word, the prefix <re-> does not indicate that a thing is becoming fine again. Instead, the <re-> prefix is an intensifier. It is intensifying the action. Whatever it is that is being refined is being made super fine.

Another example of a prefix that can intensify the action of the base is found in the word ‘corrode.’ The sense and meaning of the word since it was first attested in the late 14c is “wear away by gradually separating small bits of it” according to Etymonline. You might recognize the base as <rode>. It is from Latin and has a denotation of “to gnaw.” We see it in rodent and erode as well. The meaning connection is pretty obvious, isn’t it? That leaves <cor-> as the prefix. It is an assimilated form of <com->. We often think of <com-> or one of its assimilated forms (<col->, <con->, <cor->, or <co->) as bringing a sense of together to the base’s denotation. But that’s not what is happening here. Instead, the <cor-> of ‘corrode’ is intensifying the “wearing away.”

One more example of a prefix being an intensifier is found in the word ‘complete.’ The Latin bound base <pl> has a denotation of “to fill.” If you think about how you use the word ‘complete,’ you’ll realize that the <com-> doesn’t bring a sense of “together” to this word. The act of finishing or concluding something can be done together with others, but it can also be done alone. The prefix <com-> in this word is intensifying the “filling of something.” Check out the entry at Etymonline to see for yourself.

Concluding thoughts

I hope I’ve made it obvious that when we teach children that <con> means together and <re> means again, we are teaching them only one possible sense when the truth is there are many. There’s nothing wrong with saying that <re> typically incorporates a sense of “again” to a word it is part of as long as we also say, “but let’s check to be sure. It could be doing something else as well!”

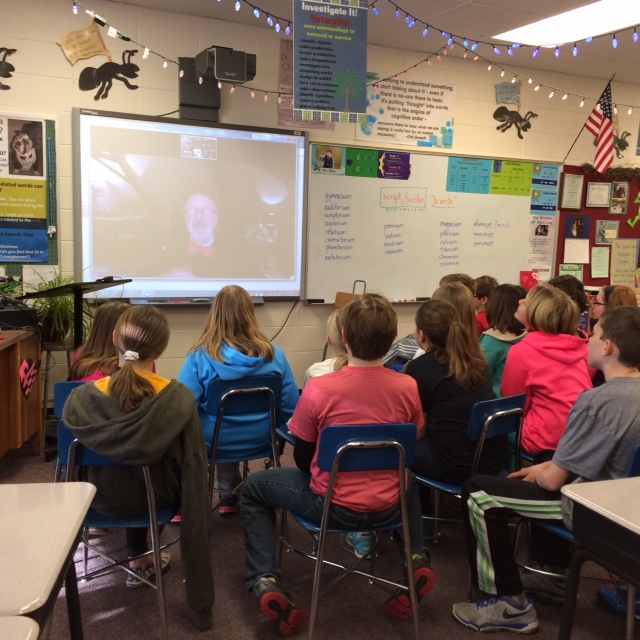

People who are hesitant to use SWI with their struggling students often say it is because their students don’t find dictionaries friendly. Mine didn’t either. That is, until they had a reason to use them. I remember the days when my dictionaries sat unused on the shelf. If I sent a student to grab one so we could look up a word, the student often said, “Nevermind. I’ll use a different word.” Since the students and I started asking questions that we were genuinely interested in exploring, those same dictionaries have become dog-eared and in come cases the pages have popped out. I couldn’t be happier! Once there was an authentic need to use the dictionaries, the students picked up the skills necessary more quickly than when we used to make up a fake scenario so they could practice. “Let’s check to make sure,” became the quick look it’s supposed to be. Students like knowing whether they’re on the right track or not, and using a dictionary lets them do that for themselves. They learn confidence by not needing to run every hunch they have by the teacher. When you avoid using dictionaries with your students because they are uncomfortable with them, you lose a huge opportunity to show them how to use reference materials and how to find out things on their own. In effect, you are helping them stay uncomfortable with them.

So do your students a favor. Make, “Let’s check to be sure,” a common practice in your classroom. Let them discover the value and worthiness of a great reference material! Thank goodness we have dictionaries and solid etymological resources like Etymonline, Chambers Dictionary of Etymology, and the Oxford English Dictionary! That is where you and your students will be able to distinguish which sense a prefix is contributing to a word! You don’t want your students to sort-of, kind-of understand the words they read and use in their writing. A quick “check to be sure” will create a solid definition of a word as well as a scholarly habit.