When people ask if I use a scope and sequence, my first response is that I don’t. But that’s not completely true. I do have a scope in mind. I do have a list of concepts and skills that I feel are important and that I must teach in a given school year. It isn’t etched in stone or anything because it depends on my audience, of course. I start where they are in their understanding of English spelling. I also have a rough sequence for some of those concepts that I generally follow. It also isn’t etched in stone or anything. It is simply an order that I generally follow so I know that I can build on some basic understanding before adding layers of new information. For example, I don’t teach my students about assimilated prefixes until they have experience with prefixes in general. I don’t teach about Latin verbs and the resulting bases in modern English until they have an understanding of Latin’s place in the history of our language. But other than that, the rest of the concepts are applied when the opportunity arises. And it arises a lot because we look at so many many words in the course of a school year.

I have used a scope and sequence with other programs in the past. I understand why teachers want them. There is always the fear that you’ll miss teaching something important or that there will be inconsistency between one teacher and another regarding the skills taught. As you go along, you can check off that you have covered a certain skill, and by the end of the year, all of your students have heard all of the required information. But we all know that following a strict scope and sequence doesn’t guarantee anything. Students can still end up with “gaps” in a specific subject. Sometimes there isn’t enough practice before the sequence timeline moves on. I’m not blaming the teacher here. I’m just saying that students who kinda-almost-get it, don’t always get it solidified before the teacher moves on to the next piece in the scope. And that is only one example of how a gap can form.

I’m not saying you have to scrap the idea of a scope and sequence. Many districts require them. But I want you to think of one in a less restrictive way. A less regimented way. If you’ve been teaching for any length of time, I bet you already know where you will start each year with the subjects you teach. You know what concepts you will start with and what comes next. It is the same for me. The difference is that once we get into word investigations, I can’t predict which concepts will need a closer look. Instead of writing down a specific order in which these concepts must be addressed, I take the opportunity to discuss them as they come up in the context of a word. In this way, we talk throughout the year about concepts that come up over and over. Before you know it, some students are able to explain these concepts to other students. When that happens, I know that the understanding will continue to spread throughout the class. More and more students will have the opportunity to explain a concept to other students and in doing so, demonstrate that they know it for themselves.

The following is a list of big topics I consider to be “must haves” for my students. I will not get into all of the particular bits included with each of these larger topics, but I em endeavoring to explain each to give you an idea of what each entails. I have other posts in this blog that address many of these things.

Words hold meaning.

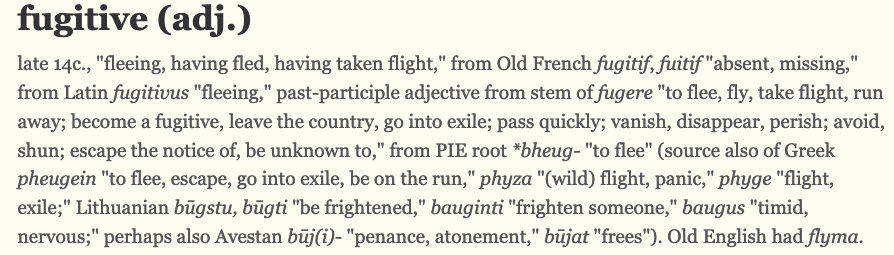

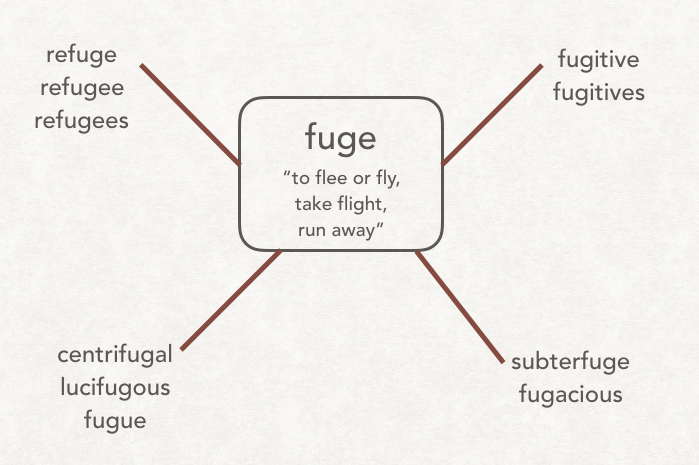

This is a perfect spot for one of my favorite quotes from Freak the Mighty by Rodman Philbrick, “Every word is part of a picture. Every sentence IS a picture. All you do, is let your imagination connect them together.” Yes, every word has a sense and meaning. And that sense and meaning is embedded in the word. It isn’t a case of, “Here’s the word. Go look in a dictionary to find out what it means.” Instead, we learn to spot the bases in a word that carry a common denotation that has existed since the birth of that lexical stem in the English language. It is a literal meaning of the word, and is comprised of the denotation of the base and the sense that is added to it by any affixes. Yes, sometimes a word’s sense and meaning changes over time, but there are a surprising number of words that can be clearly understood once one knows the denotation of the base.

Words have structure.

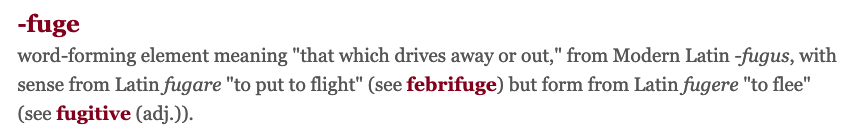

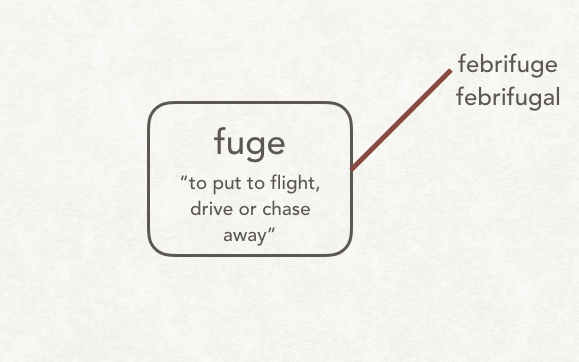

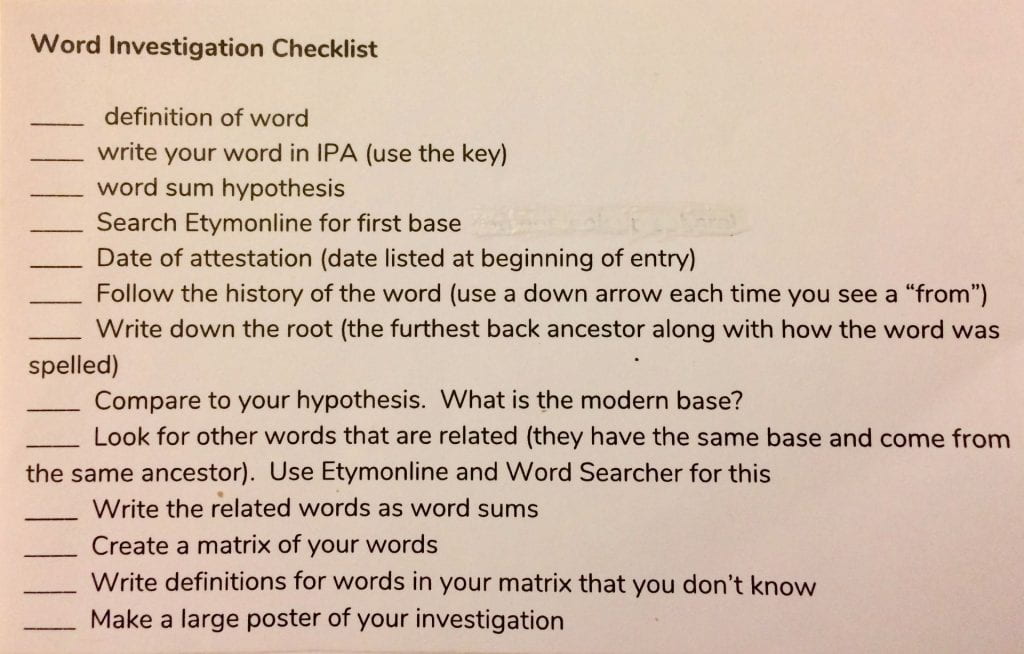

A word’s structure is expressed by writing its word sum. We begin with a hypothesis. Familiarity with affixes is a must, but I don’t recommend memorizing them in isolation. I find it helpful to look at prefixes and suffixes by having small groups collect words with a specific suffix or prefix. Then we come together to talk about what these affixes are and how they steer the denotation of the base. After a day or two of that, I continue those discussions about affixes as they come up in word investigations. If I see some confusion about the role of affixes, the sense they carry, or what happens when two or more are joined, I will choose a specific word family for examination that will help solidify this familiarity.

About half way through the school year, when I feel that my students are comfortably familiar with several common prefixes, I specifically have everyone learn about assimilated prefixes. Many students know that <con-> and <com-> are prefixes. But they don’t know that they are in fact forms of the same prefix. And they don’t imagine that <col->, <cor->, and <co-> are even prefixes at all! This is something I have students focus on in small groups. They collect words that have one or another form of that prefix so we can share and talk as a class. We all benefit from each group’s research, and they become better equipped to make hypotheses about word sums!

Connecting vowels are something we discuss when they appear. The first time we spot them, I spend time explaining how I know that the letter in question is, in fact, a connecting vowel. I demonstrate the questions I ask myself and the resources I use. I also point out that you can’t tell if a letter is a connecting vowel by just looking at the word. You can have a suspicion, but it isn’t until we have asked ourselves some questions and used our resources that we can provide evidence to back our suspicion or hypothesis.

This brings us to identifying bases and whether or not a word is a compound. They know about free bases except they call them roots. We clear up that distinction. The idea of a bound base is completely new to my students. They have been told about adding suffixes and prefixes, but with that being said, they do not know that a word like <corrode> is made up of a prefix and a bound base (a bound base simply being a base that needs an affix). By the end of the year, they are delighted to be able to say that technology, manufacture, geography, and hallway are all compound words!

Besides learning about free bases and bound bases, they learn that some bases that derived from Latin verbs have alternate spellings. They come from the same Latin verb and have the same denotation, but have two or more spellings. An example of this would be the bases <duce> and <duct> that we see in <produce> and <product>. The bases derived from Latin verbs are so commonly seen in modern words that this is definitely a worthwhile focus for my students. By the end of the year they have gained so much in the way of understanding about the types of morphemes a word can have, that hypothesizing word sums is one of their favorite activities!

Words come from somewhere.

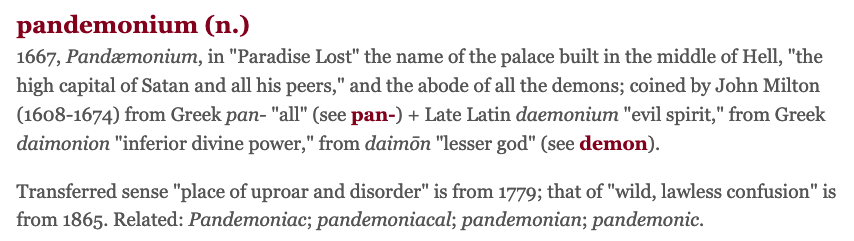

Some words have been around for hundreds of years. Others are newer. Words are being added to our English lexicon all the time. Our language is always changing, and those changes are brought about by the people who speak the language. In other words, words have a history and that history becomes their story. This is the facet of structured word inquiry that always draws my students in. They love knowing that words were, in effect, born at some point in time. In some cases the spelling of a particular base was influenced by other languages and changed along the way. In other cases the meaning of the word as it was used by people over time changed rather drastically! It could be that the word now means the opposite of what it once did! And, of course, there are many words that have retained their spelling and their sense and meaning.

In the course of conducting word investigations, students find out that words may have come from a number of different languages. Generally, they find that the majority of the words they look up come from either Old English, Latin, or Greek. At first I just let them get used to the idea that the words we use came from languages such as these. But by late in the first half of the year, I think it’s time to put those languages in perspective. What I mean is to look at a timeline and think about how long ago Old English was being spoken! Is Greek older than Latin, or is Latin older than Greek? In small bits, I present some of the history of our language. I talk about Proto Indo European. It makes sense to do so since it is referenced so often at Etymonline!

While we are looking at the language of origin, we take note of certain signals in the spelling of a word that might point us in that direction. For example, when we see a medial <y>, we see that as a clue that this word is no doubt from Greek! Or when we see the spelling <ch> and the pronunciation of /ʃ/, we see that as a clue that this word is from French. There is just so much understanding to be gained by knowing more about the ancestors of our modern words!

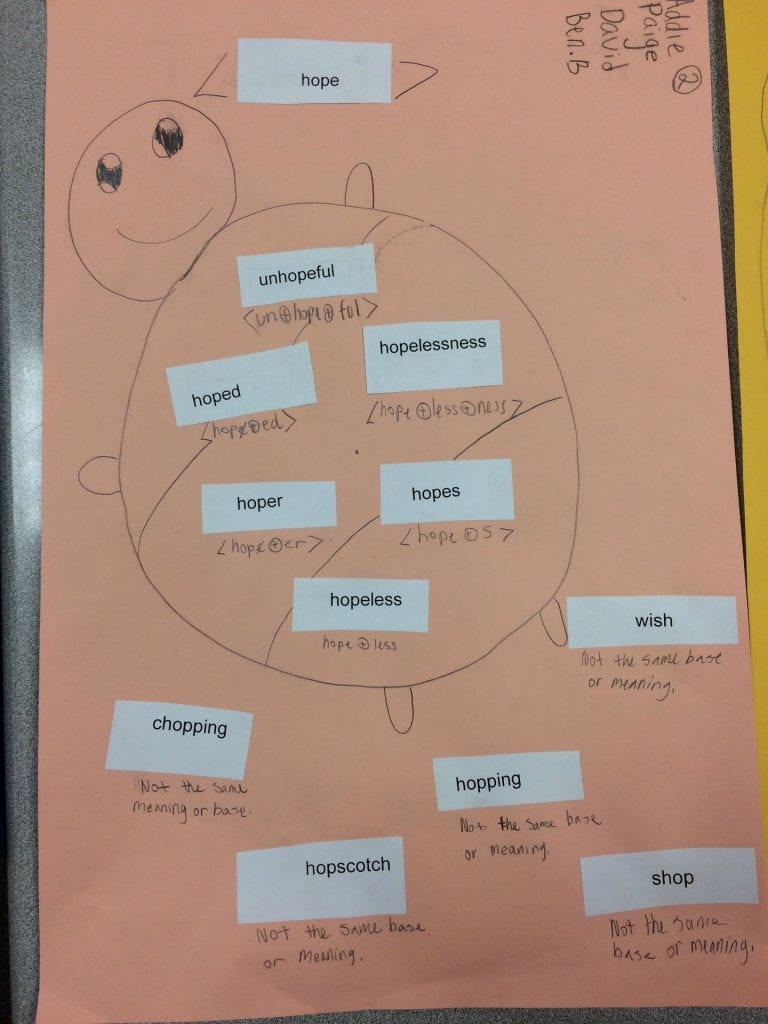

Words are not used in isolation, so they should not be studied in isolation.

So much of Structured Word Inquiry involves a scientific “compare and contrast” model of thinking. If we look at a word all by itself and try to understand its spelling, we are lost. But if we look at a word among its family of relatives (meaning other words that share its base and etymological ancestor), we can learn so much more. When we are studying and analyzing the grammar in a sentence, we look to the affixes on the words to give us clues about how the word is functioning within the sentence. We notice that some suffixes are unique to specific parts of speech while others need to be seen in the context of a sentence. For example, when we see <-ion> added to <animate>, we think of the new word as a noun instead of a verb. But a base with an <-ly> suffix needs the context of the sentence to reveal its part of speech. Two possibilities are that it can be fixed to a noun to become an adjective (as is the case with <elderly>) or to an adjective to become an adverb (as is the case with awkwardly).

Graphemes are another aspect of English spelling that needs to be understood in context of the word they are part of. So many of the graphemes in English have the potential to represent several phonemes. When we investigate the word as a whole, the etymological origins or journey can give us an understanding of why certain graphemes are used over others or why the grapheme we see represents a specific phoneme. An example I am thinking of is the <ch> digraph which might represent the /ʃ/ phoneme in words like <chef> or <ricochet> that came from French, yet represent the /tʃ/phoneme in words like <chair> and <search> that came from Old French and further back, Latin.

Words are ours to enjoy!

Words should be appreciated because they are a reflection of the people who use them. The dictionary isn’t a collection of the words we should be using. It is a collection of the words we are using. Every year we hear about words that are removed from the dictionary because no one uses them, and also, new words popping up and being used often enough to need to be added to the dictionary. You see, dictionaries are a reflection of the words we use. Each edition is a snapshot of use in that year. Luckily, most words hang around a long time and so we don’t notice the age of a dictionary unless we are looking for a recently added word.

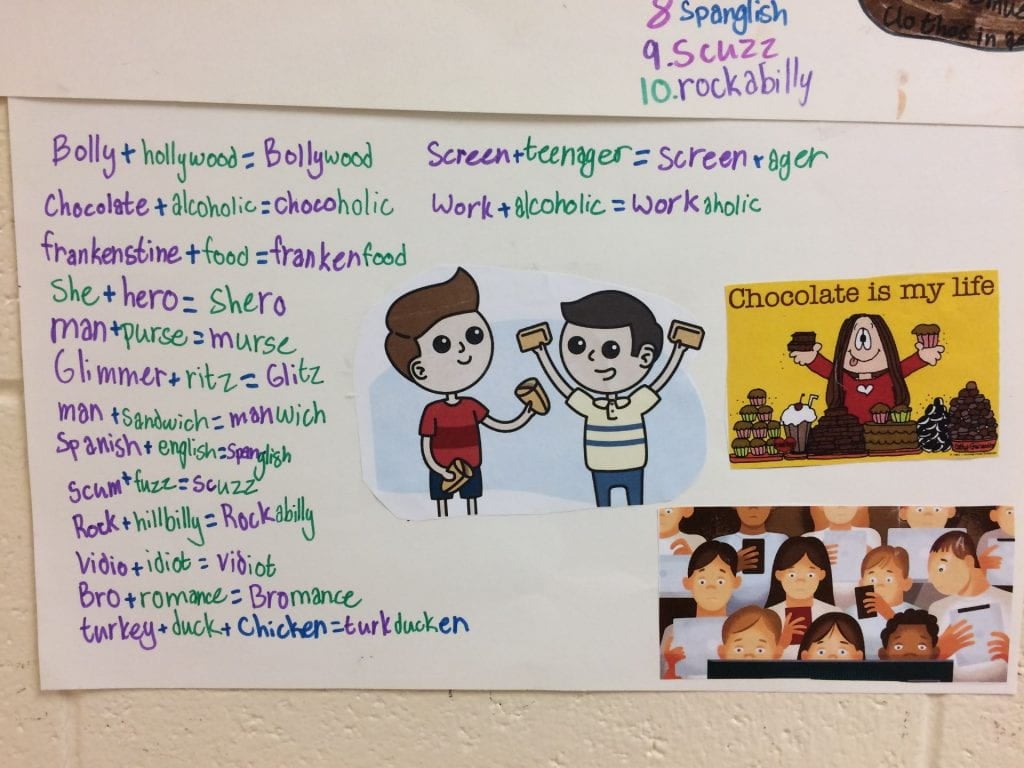

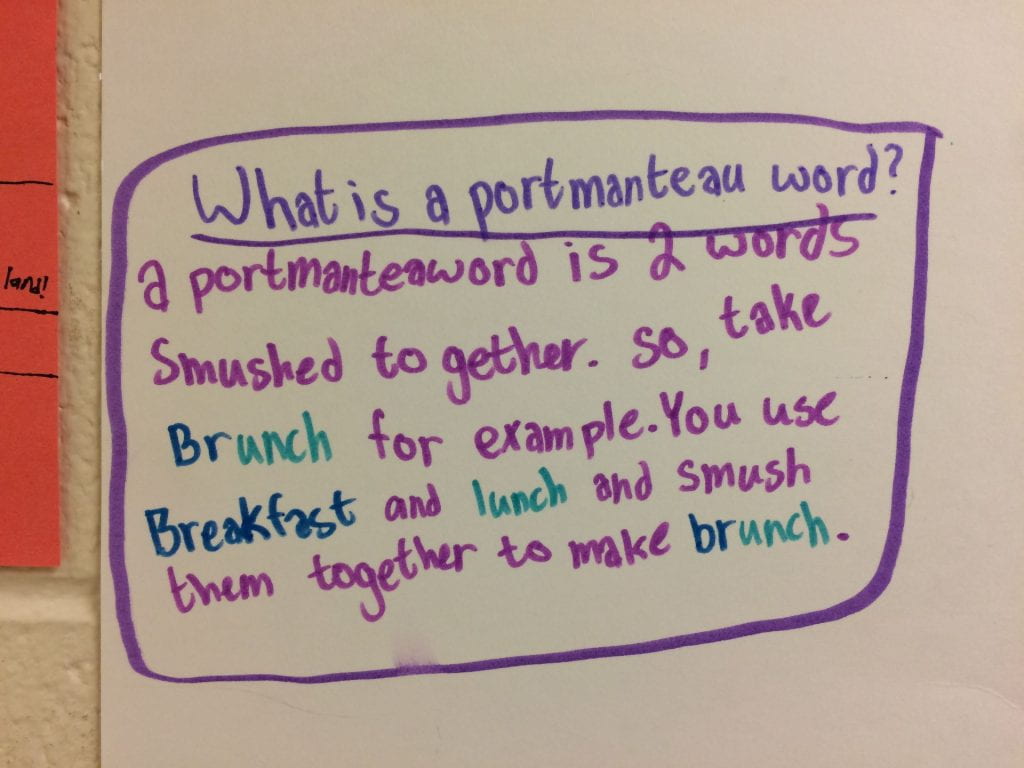

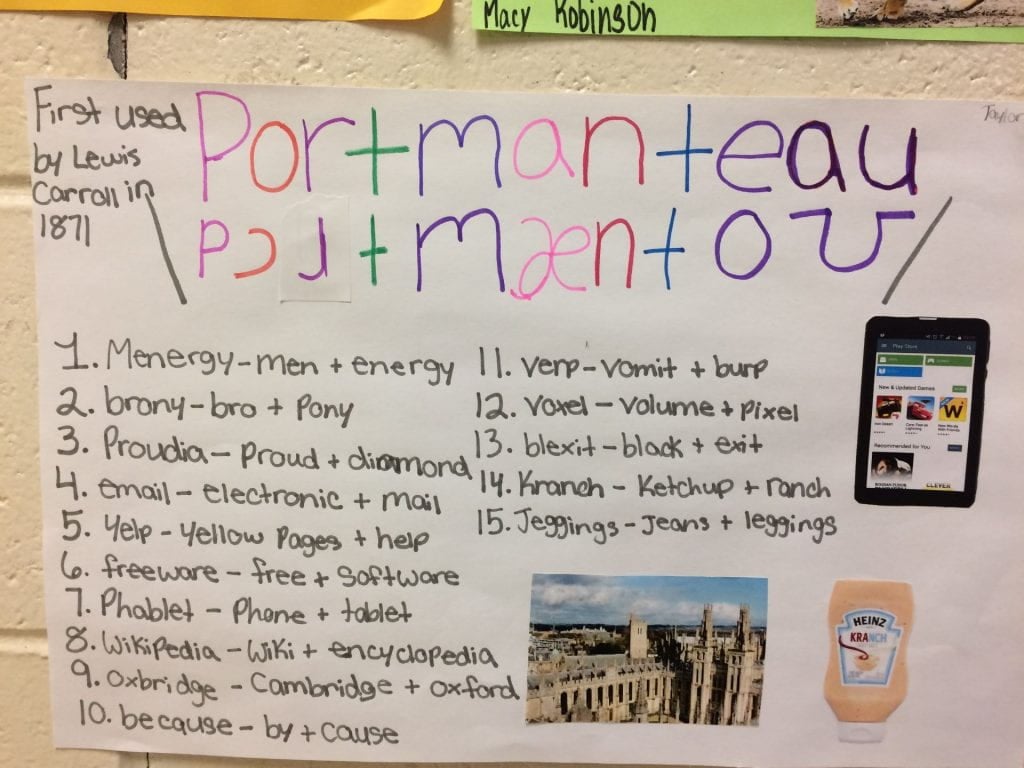

Students are so used to dry vocabulary lessons and spelling tests, that they lack curiosity and/or enjoyment of words. I feel it is important to reinstate that idea. To that end we look at things like portmanteau words, phonesthemes, extremely long words, and oxymorons. The children discover that words can be playful and even make us laugh. They enjoy discovering that motorcycle is a portmanteau word that blends the words motorized and bicycle into one! They find satisfaction in knowing that email is a blending of electronic and mail.

Phonesthemes are so intriguing! They are not a spelling, but rather a common pronunciation found in a group of words that also share an aspect of their meaning. The words are not necessarily related etymologically, but there is a common “sense” among them. An example would be /sn/ which is part of snore, snout, sniff, snot, snarl, snort, and sneer. Have you already guessed what “sense” they share? Right. They all have something to do with the nose.

Oxymorons are simply two words with an opposite meaning paired together. A few examples would be seriously funny, jumbo shrimp, and awfully good. By giving students the opportunity to see words in this way, we make them inviting. Words become something to share and talk about enthusiastically!

I hope you can see that I have a master plan. I definitely have a master plan. There are certain parts of this plan that need to be addressed right up front. For instance, I always start with showing students that words have structure and can be written as word sums. That is an idea that is never checked off as having been “covered.” It is a part of every investigation and every inquiry we do all year. And we spend a lot of time throughout the year conducting word investigations. We do them as a whole class, we do them individually, and we do them in small groups.

The rest of the concepts I’ve listed overlap each other all the time throughout the school year. I don’t feel there is one order that is more correct or makes more sense than another. If I see something in a word investigation that I can illuminate, I do. If I notice a misspelling in a writing sample that I think needs attention, I will do just that. I will write a similarly misspelled word on the board so we can talk about the concept that needs to be applied in that given situation. I am not teaching my students to spell one word at a time, but rather to learn the consistent and predictable conventions that English has, so they can apply them to the words they encounter every day.

I watch their reactions to what they are hearing. I vary what I do day to day to keep them engaged. If I think the current activity is losing momentum, I will take a break from it and show some kind of orthography-related video. Often, doing a bit of sharing about current projects gets everyone back on track. I always let them work in small groups so they can talk through what they are doing. You are encouraged to keep an eye on the groups to make sure all are involved in the talking, the researching, and the writing. We always do a large group sharing of small group projects. It is this time spent sharing projects that leads to the understanding of words, their meanings, their structure, and their stories. It is when everything settles in and over time, with repeated presentations and discussions, becomes permanent information.

I mentioned earlier that there are certain inquiries that I hold off on until the students have a more solid understanding of a word’s structure, and of how to use Etymonline, our dictionaries, Word Searcher and toPhonetics. That makes sense to me since another goal is to consistently increase their level of independent investigation. My students know that I welcome questions, but they also learn that I will turn the question back on them if I think they can answer it themselves. I don’t investigate for them or hand them everything they need to make anything easy. And they appreciate that. It is one of the comments I have been hearing every year since 2012 when I first incorporated Structured Word Inquiry into my teaching. This is fun because they get to find out things for themselves. And that’s the way learning should be!