Ricard Canals (1876 – 1931) Sick Child (Octavi, the artist’s son) c1903

I received a scary call a few weeks ago from my daughter. My 3 year old granddaughter had just had a seizure and her dad was with her, at home, waiting for the ambulance. My daughter, who had called from her car, was on her way home from work and had just picked up her younger daughter from daycare when she received the call from her husband. He had stayed home with June, who was sick with the fever and yucky feelings that had been going around her preschool.

We were all so scared. I was immediately picturing my granddaughter and what was happening to her. Was she scared? How out-of-it was she? How long did it last? But then I thought of her parents and how scared they must have been. It pulled at my heart to know all any of us could do was wait and see now. I am still my daughter’s mom and number one worrywart of her emotional and physical well-being. I have also grown to see what a truly wonderful husband and dad my son-in-law is, and I knew this had no doubt scared the liver out of him.

I’ll keep you in suspense no longer. After five hours at the hospital, and after having ruled out that the seizure was caused by a Urinary Tract Infection or by the small skin infection she had on her finger, it was decided that she had a febrile seizure. A febrile seizure is one caused by fever. Children can have febrile seizures if their fever spikes unexpectedly and if this kind of seizure is present in the family history. It turns out that this happened to their nephew as well. They usually don’t happen after the age of 6, but because she’s had one now, she is more likely than other children to have another. It was certainly scary! Moving forward, we will all watch for signs of fever with vigilant eyes.

It wasn’t until a few days later and everything was calm again that I could think more about that word <febrile>, and wonder if it was related to February. You see what happens once that dark cloak of “memorize the dictionary definition and you’ll be fine” has been lifted? So many words catch my attention now. This one was less common and therefore caught my attention right away.

According to the Chambers Dictionary of Etymology, febrile is an adjective “of fever, feverish” first attested in 1651. It was either borrowed through French fébrile, or directly from Medieval Latin febrilis. Earlier it was from Latin febris “a fever.”

At the Oxford English Dictionary I found this sentence from 1483, “Al that yere she was seke and laboured in the febrys.” There were also the spellings febres from 1527 and febris from 1535. Besides these Middle English spellings, I found other relatives. I put them in chronological order according to their date of attestation. The words with the asterisk are obsolete, although many of the others (as you may guess) are rarely used.

febrous – adj., as early as 1425, “affected with fever.”

*febris – n., 1483, “a fever.”

febricitant – n., adj., ?1541, “affected with fever.”

*febricitation – n., 1598, “the state of being in a fever.”

febrile – adj., 1651, “feverish.”

*febrient – adj., 1651, “feverish.”

*febricitate – v., 1656, “to be ill of a fever.”

*febriculous – adj., 1656, “slightly feverish.”

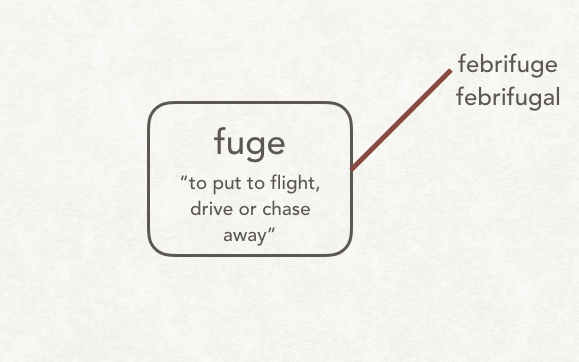

febrifugal – adj., 1663, “adapted to subdue fever.”

*febrifugous – adj., 1683, “adapted to subdue fever.”

febrifuge – adj., n., 1686, “a medicine to reduce fever.”

febrific – adj., 1710, “producing fever.”

febriculose – adj., 1727, ” slight fever.” Also febriculosity.

febricula – n., 1746, “fever of short duration.”

febrifacient – adj., n. 1803, “fever producing.”

febricity – n., 1873, “the state of having a fever.”

febriferous – adj., 1874, “producing fever.”

febricule – n., 1887, Anglicized form of febricula “slightly feverish.”

Isn’t it something to see the variety of spellings/uses for this word over 400 years? As you read through the list, do you recognize the suffixes that signal nouns and adjectives? I’m fascinated that in that entire list there is only one form used as a verb. <febricitate>. Do you notice the <ate> suffix there? It was used as a noun first, <febricitation>. This <ate> suffix signaling a verb but then changing the function of the word to a noun by the addition of an <ion> noun, is something I always look at with my students. In the following list, the verb form is first and the noun form is second.

precipitate, precipitation

illuminate, illumination

infiltrate, infiltration

hydrate, hydration

illustrate, illustration

Once I get them started, they continue the list on their own. Once they see this for themselves, and they know the suffixing convention of replacing the single final non-syllabic <e> on an element when adding a vowel suffix, they don’t believe people who tell them that *<tion> is a suffix. I don’t have to convince them of that fact. The evidence that they have collected convinces them.

There’s just so much to notice about this list! As I was putting it together and announcing the words to myself, I have to say that <febriferous> was my favorite. I laughed at myself trying to say it even two times in a row! Perhaps you’ll have better luck?

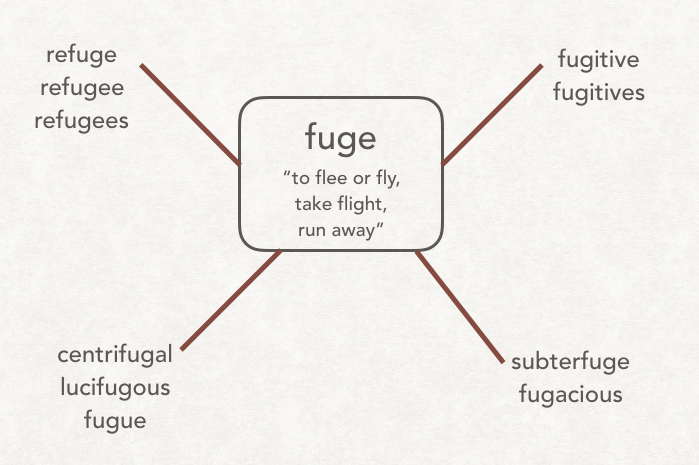

Other relatives that stick out to me are febrifuge, febrifugal, and febrifugous. You’ve probably noticed the second base there, <fuge> from Latin fugare “cause to flee, put to flight, drive off, chase away.” A febrifuge is a medicine that will drive off the fever. I love imagining my little June’s fever being driven off by little medicine superheroes!

Interestingly enough, I came across the word <feverfew> which is from Old English feferfuge. (Do you notice what I noticed? – that that second <f> in the Old English spelling is the unvoiced version of <v>?) Earlier it was from Late Latin febrifugia, from Latin febris “fever” and fugare “put to flight.” According to Etymonline, this modern English word is probably a borrowing from Anglo-French. According to information at Wikipedia, feverfew was used as a traditional herbal medicine, but is no longer considered useful for reducing a fever.

Feverfew (Tanacetum parthenium)

By Vsion (2005). Photo via Wikipedia public domain.

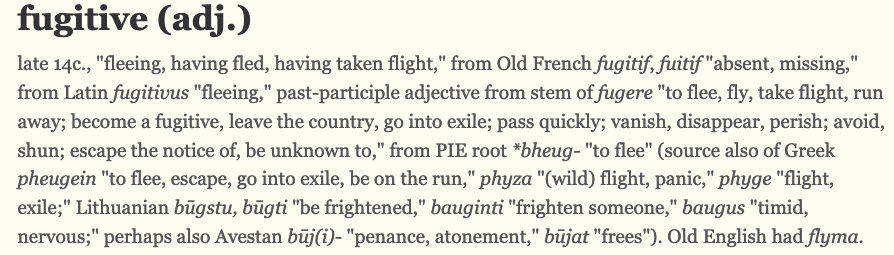

Getting back to the word <febrifuge> and the second base in that word <fuge>, I pondered that sense and meaning of “cause to flee, drive off, chase away,” and it made sense to me that this must be the same <fuge> that I see in <fugitive>. So I went to Etymonline and looked at <fugitive> to make sure that they shared the same ancestor. This is what I found:

Although this seems to be a match, I noticed something about both the spelling of the Latin verb this word is from and the denotation of that verb. This word derives from Latin fugere “to flee, fly, take flight, run away, go into exile,” whereas the <fuge> in <febrifuge> comes from Latin fugare “cause to flee, drive off, chase away.” Do you see the difference in spelling of the Latin verb for each? They each have a different infinitive suffix. That means they are two separate Latin verbs! Then I looked closely at the denotation of each and realized that the Latin verb fugare has a sense of chase away something and the Latin verb fugere is the thing that has been chased away or has taken flight! I wanted to find out related words for each so I went back to Etymonline.

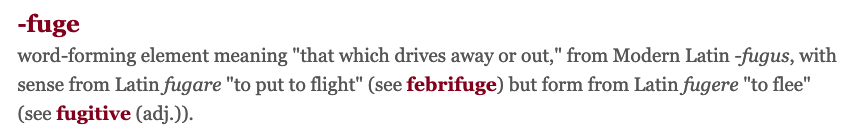

First I typed fugare into the search bar. That way I would probably find words whose ancestor is the Latin verb fugare. I found only three entries: feverfew, -fuge, and febrifuge. I found something very interesting in the -fuge entry.

Look at the line following the bolded <febrifuge>. It says, “but form from Latin fugere.” I interpret that to mean that Latin fugere existed in words earlier than Latin fugare. I took a quick look at <fugitive> in the OED and sure enough, the word is attested in 1382, which is earlier than <febrifugal> which was attested in 1663!

It was time to look at Lewis & Short. The infinitive form of the Latin verb is the second one out of the four.

fŭgo, fŭgare, fugāvi, fugātum

“to put to flight, drive or chase away”

fŭgĭo, fŭgere, fŭgi, fŭgĭtum

“run away”

Yep! Two separate verbs with two separate yet related denotations. One has become more productive than the other, hasn’t it?

#####

There is a very thought provoking comment at the end of the post that I encourage you to look at. It is written by someone who has studied Latin at a deeper level than I have. She has been collecting Latin verbs, including the two I have pointed to above. I am thinking carefully about what she has said, and I encourage you to do the same. I know there is no rush in scholarship, so I’m not concerned that I don’t completely embrace yet what she is pointing out. I have questions to pose before then. This is the way scholarly learning works. I don’t take anyone’s word for anything. I need to understand things for myself. I appreciate things being shown to me, but unless they make sense to me, I must keep questioning.

#####

Now that I’ve followed that interesting path, I’d like to get back to my original question. Is <febrile> related to <February>? I bet that at this point you’re guessing that it is not. If it was, wouldn’t it have shown up as a related word in the OED? So if it isn’t related to “fever”, what is it related to?

Looking further at the Chambers Dictionary of Etymology, I can add to that that this idea of purification refers to the Roman feast of purification held in February, which at that time was the last month of the ancient Roman calendar. It was after 450 BC that it became the second month and was called solmonath by the Old English which meant mud month.

The base <febr> “fever” may have had many related words a few hundred years ago, but not that many of them are still in use today. The word that we commonly use is <fever>. Does that mean it’s a newer word? Interestingly enough, it’s not. According to Chambers, it developed from Old English (c1000) fēfer, fēfor. It was borrowed from Latin febris “fever” and is related to fovēre “to warm, heat.” Later on in Middle English (1393) it is spelled fievre where it was borrowed from Old French fievre, which was from Latin febris.

This word also has a lot of related words that have become obsolete.

We no longer use:

feverly – adj., 1500, “relating to fever.”

feverable – adj., 1568, “characterized by having a fever.”

feverite – n., 1800, “a person ill with fever.”

On the other hand, many related words I found at the OED are still very much in use today:

fever – n., 1000, “abnormally high body temperature.”

fever – v., early OE, “affected with abnormally high body temperature.”

fevery – adj., OE, “affected by fever, perhaps causing fever.”

fevering – adj., ?1200, “becoming feverish.”

feverous – adj., 1393, characteristic of having a fever.”

feverish – adj., 1398, “relating to fever.”

fevering – n., 1450, “a feverish state.”

fevered – adj., 1605, “showing symptoms associated with a high temperature.”

feverishness – n., 1638, “the condition of having a fever.”

feverishly – adv., 1640, “in a manner relating to a fever.”

feverless – adj., 1662, “without a fever.”

fever tree – n., 1727, “bark of certain trees used to treat fevers.”

Take a look for a moment at the above list and notice how many of those words you have used. Then notice how old those words are. Words amaze me every day. There is so much to know and so many connections to make! I can’t help but wonder about these two bases, <febr> and <fever>. They both share the Latin root febris and the same denotation, yet the one is much more recognizable than the other. The <febr> base is still around, but probably more well known in the medical field. The sciences are full of words with roots in either Greek or Latin. The <fever> base is still very much around also, and known well by the common people — by the ancestors of the common people who spoke the Old English language.

One of my very favorite things to discover are bases that look the same but aren’t. Today I found two! I wouldn’t have done so without the help of excellent reference materials, and without having been taught how to use those materials. I am grateful that for now my granddaughter is feverless, but like I said earlier, her parents are vigilant. Should she get a febriferous illness again, they are ready with a febrifuge.

Below is a picture of Cinchona pubescens. This is an example of a fever tree. According to Wikipedia, the bark of several species of this flowering plant yields quinine which was an effective treatment for the fevers associated with malaria up until 1944.

Credits : US Geological Survey – Photo by Forest & Kim Starr