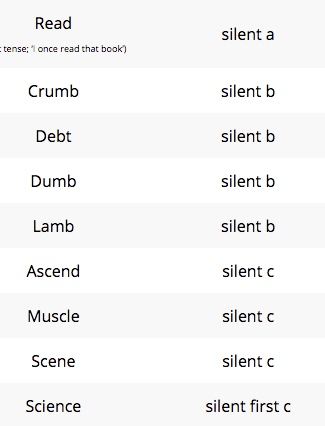

I found an article the other day that made me kind of sad. The article was posted online by the Oxford Dictionaries and was called, “Why English is so hard to learn: silent letters.” Here is a link to the article. The first thing that struck me was the term “silent letters”. I am aware that letters that are unpronounced in a word are commonly referred to as silent letters, but that doesn’t make it accurate. I also admit that in the not too distant past I called them that as well … because that was what I was told they were. In a world where children are taught that letters routinely “say” sounds, as in the letter f says /f/, it might indeed seem to make sense to call the <g> in <sign> silent since it isn’t “saying” anything.

But I’ve come to realize how misleading that way of thinking is. And it is. Very misleading.

Letters produce sound?

Let’s begin with the underlying assumption here that letters do make sounds. Obviously they do not. Can not. They’re just symbols printed on paper. Yet we ask children to believe that they do. In fact we begin a child’s reading instruction by teaching them that the consonants each “make” one sound and the vowels each “make” two. What we really mean here, and what we should really be saying to children is that graphemes represent pronunciation. (Graphemes are letters or combinations of letters that represent phonemes.) So for example, we can say that the grapheme <s> represents /s/. But don’t stop there. If you don’t want to get into all of the pronunciations that the grapheme <s> CAN represent, then just say, “The grapheme <s> CAN represent /s/. It can also represent other pronunciations, but right now we’ll focus on /s/.” Using this wording leaves the door open to other pronunciations of the grapheme <s> as they will, without any doubt, notice in words. The students won’t be gobsmacked when it happens. They will have been waiting for it and looking forward to understanding why and when <s> has other pronunciations.

With this slight change in OUR explanation, we are switching from having children think something is possible (that even THEY can recognize is not) to simply stating the truth. Changing your wording may seem trivial to you as you are reading this, but within a year or two of learning to read and write, children are already beginning to see our language as one that makes no sense. And the fact that the adults don’t understand our language as well as they could, doesn’t help. Many just repeat what they were taught or what some teacher manual says to repeat. They don’t question what they don’t understand because their own education regarding our language has unintentionally taught them to believe that our language makes no sense. I imagine that you have seen the same kinds of “proof” that I have where someone asks about house and mouse, and that if the plural of mouse is mice, why isn’t the plural of house hice? There are lots of those kinds of questions offered up as proof that English spelling cannot be understood. And perhaps, if the only aspect of English spelling that has been presented is that of the “sounds” of letters and words, then of course it might feel impossible to understand.

Learning grapheme, digraph, and trigraph pronunciations in isolation?

Can you imagine teaching children to read music by holding up a card with a musical note drawn on it and expecting them to sing it? Of course that wouldn’t work because until they see the note on the proper line of the musical staff, or hear it in comparison to the note in front of it or behind it within a song, they won’t know the right note to sing. Expecting children to recognize and accurately sing all of the notes before they see any of them on a staff or in a measure of music is ludicrous. Before children learn to read music, they have sung hundreds of songs. They have sung the notes in hundreds of combinations. But not in isolation. Each note makes sense in its setting, in the context of its song.

Is it so different with children who are learning to read? Why don’t we teach them graphemes, digraphs, and trigraphs in the context of a word or even a sentence? Because THAT’S where those pronunciations become clear and predictable. Perhaps begin with a word that is used in a story you are reading. The child can get a feel for how the word is used and what it means by pulling it out of context for a closer look. Maybe you’ll want to think of other words related to this one. For example, if you are focusing on the word ‘dog’, maybe you want to talk about a dog house or dog food or dogs. You can both count how many letters are in the word. Then point out that each letter in this word represents a grapheme, and that each of those graphemes represents a phoneme. Then pronounce each. You might point out that in any word that has a final <g>, that <g> will be pronounced /g/. Then you can brainstorm some other words with a final /g/. Then again, maybe the student wants to pick out a word to look at. Maybe it could be routine that every time you read a story together, you each pick out a word to look at and think about. Review the names of the letters and compare the way graphemes are pronounced in words. For example, compare the <s> in small to the <s> in dogs. Find some other words with a final <s> and practice reading the words together and feeling whether the final <s> in those words is pronounced /z/ or /s/. This might even be that opportunity to find graphemes in words that are unpronounced!

It is common practice to teach graphemes and digraphs in isolation. I remember back a bunch of years. Our spelling list included words in which the main vowel was called “long e” and pronounced as /i/. The students would brainstorm different letter strings we could use to represent that pronunciation. We came up with <ee> as in reel, <ea> as in read, <ei> as in received, <ie> as in chief, <e> as in be, <y> as the final letter in baby, and <e_e> as in these. Every week we would brainstorm these patterns and then think of words that used those spellings for that pronunciation. What busy work! The students would ask, “How do you know which of those spellings is in a particular word?” I couldn’t answer because I didn’t know. After a while they stopped asking and they resigned themselves to empty memorization. What I was doing didn’t make them better spellers unless they were already great at memorizing. You see, looking at the vowel pronunciation and all the letter strings that might represent it just made matching them up feel very random. To the students, it was like playing “take a guess.”

It makes much more sense to start with a word that a student has come across and that they are interested in.

So why are some letters in some words unpronounced?

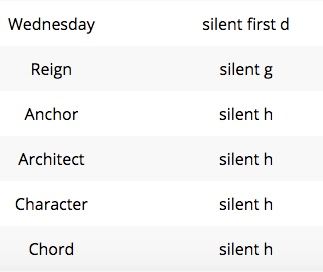

Let’s focus on some of the letters identified as “silent” in the article. We’ll look through a few at a time so I can explain some possible reasons for that letter not being pronounced in that word.

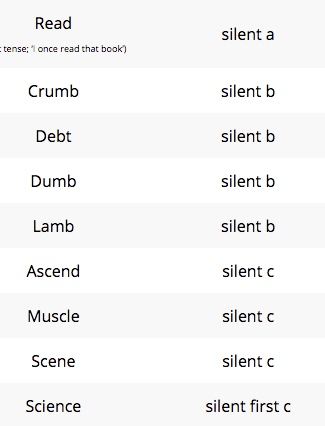

Let’s begin with read, as in “She read that book yesterday.” The <a> cannot be considered unpronounced because it is not functioning independently in this word. It is part of the digraph <ea>. That means that the two letters are representing one grapheme which is representing one phoneme. In this word, the digraph <ea> is representing /ɛ/ as it does in bread, feather, and breath. This digraph can also represent /i/ as it does in team, eat, and bean. The fact that this one digraph can be representing two different phonemes makes it perfect for this word. If you look at other words in this family, you’ll see that both of these pronunciations are present: <ea> as /i/ – read, reading, readable, reader, readability, readership, misread, and <ea> as /ɛ/ well-read, read, misread. The meaning of this base is constant, but the pronunciation of the base is dependent on the context in which we find it, as well as the affixes attached to it.

The next word on the list is crumb. The <b> in this word is considered a marker letter. It is marking its connection to other members in its family in which the <b> IS pronounced. That would include words like crumble, crumbling, and crumbled. If the <b> were removed from <crumb> just because it is no longer pronounced, we would not recognize this word as belonging to this word family and sharing its meaning.

Since dumb and lamb have a similar placement of <b>, let’s look at them together. These two have a similar story. The final <b> in both of these words marks their etymological origins. The word dumb is from the Old English word dumb. At that time it meant “silent, unable to speak”. Even though it has come to mean other things as well, its spelling has not changed. The word lamb has a story that is not very different. It is from the Old English word which was spelled either as lamb, lomb, or lemb depending on where one lived. In both dumb and lamb, the final <b> has been there from the beginning. And even though we don’t pronounce it, it is part of this word’s identity. When we see words like lambskin, lambkin, and lambswool, we instantly know these are related to the animal we know as a lamb.

In Modern English spelling, the consonant cluster <mb>, when found final in a word, is considered to be unpronounceable. In that case, the last letter in the word is unpronounced. This explains why we don’t pronounce the final <b> in crumb, dumb, lamb, tomb, bomb, and thumb, yet we DO pronounce that <b> in related words like thimble, crumble, bombard, and rhombus.

The word debt has a very interesting story to tell. It’s etymological journey begins in Latin with debitum “thing owed.” Its spelling changed for a while because of a French influence (dette, dete). Sometime after c.1400, the <b> was restored. So once again, this unpronounced grapheme marks a connection to this word’s root. It is interesting to note that the <b> IS pronounced in the related word debit where we see the two graphemes separated by a vowel.

Next up is ascend. This word is from Latin ascendere “to climb up, mount.” The <c> would have been pronounced /k/ in Latin. When we compare it to descend, we can hypothesize that the base element is <scend>. The prefix is an assimilated form of <ad-> “to, near, at”. The Etymonline entry for this prefix states that the <ad-> is simplified to <a-> before an <sc>. That gives us information about the word’s structure, but not the pronunciation (or lack thereof) of the <c>.

In thinking about the <c> here, I wondered whether or not it IS pronounced in words in which it appears to be paired up with the <s>. I went to Word Searcher and found a long list of words with an <sc> letter string. Here are a few of them: scone, scope, scoot, scrub, screw, scab, scale, scarf, scream, and rescue. I also noticed other words in which the <c> seemed to be unpronounced. Here are a few of them: descent, scion, scenic, scent, obscene, scepter, scissor, and scythe. In looking at the lists it became obvious to me that this is just a case of knowing the pronunciations that can be represented by the grapheme <c> and what governs that. When followed by an <e>, <i>, or <y>, it will be /s/. When followed by anything else, it will be /k/. When the <s> AND <c> in a word would both be representing /s/, they function instead as a digraph representing a single /s/.

Two other words in this list have the <sc> pronounced as /s/. The first is scene. This word originated in Greek as σκηνικός “of the stage, scenic, theatrical.” It is transcribed as skenikos. When the Greek suffixal construction <-ikos> was removed and this word was transcribed into Latin, the <k>’s were written as <c> (scene), but the pronunciation of the <c> remained /k/. As had happened in many many instances, this word was influenced by Middle French speakers (scéne) and the <c> lost its hard pronunciation. Today we can recognize the <sc> as a digraph representing /s/.

The last word in this group is science. This word is from Latin scientia “what is known, acquired by study.” If we further analyze this word, we find the base element of <sci> “know, be able to separate one thing from another.” It’s the same base we see in conscience, unconscious, and conscientious. Do you see the meaning connections there? Isn’t that fascinating? A tangent, I know, but sometimes I can’t help it! Back to the phonology of the <c> in science. In Latin, the <c> would have been pronounced as /k/, but like scene, as this word journeyed through time, it was influenced by French speakers – (Old French science). The <c> took on a /s/ pronunciation which persists today.

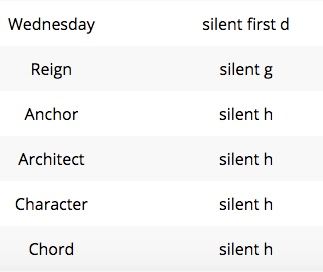

It’s time to look at Wednesday. This day of the week was originally named for the Roman god that corresponded to the planet Mercury. That is why the Romance languages (French, Italian, Spanish, etc.) spell this day as Mercredi, Mercoledi, and Miércoles respectively. When the Germanic people adopted this naming of the days, they switched out the Roman gods for their own gods who had similar characteristics. The day known as Dies Mercurii to the Romans became known as Woden’s Day to the Germanic people. Can you see now how Woden’s Day became Wednesday? There is a slight difference with the letters which no doubt prompted the <d> to lose its pronunciation. Once the <en> in Woden was reversed and the <o> changed to an <e>, the <dn> letter string became less pronounceable. If you say the word ‘Wednesday’ several times, you can feel the elision happening and the <d> becoming unpronounced.

Next up is reign. The Etymonline entry shows that the verb form of this word is from Latin regnare “be king, rule.” Moving forward through time, this word was adopted and adapted in Old French where it was spelled regner. In its noun form it gained the <i> and was spelled reigne. Seeing that the <gn> has always been part of this word’s spelling, I looked for relatives of this word to see if the <g> is pronounced in any of those. I found the words regnant “reigning, exercising authority” and regnal “pertaining to a reign.” So it seems that in Modern English the <g> is pronounced when the base is <regn>, but not pronounced when the base is <reign>.

Next on the list is anchor and what an entertaining story awaits! The Etymonline entry lists this word as beginning in Latin as ancora “an anchor.” The information there also points to the Greek ankyra “an anchor, a hook” as being either an earlier ancestor or perhaps a cognate (emerging at the same time). This information is especially interesting because of the Greek letter kappa being transcribed to the Latin <c>. A modern English <ch> spelling that is pronounced as /k/ usually originates from the Greek letter χ (chi) which was transcribed into Latin as <ch>. That did not happen here. So why is the <ch> representing /k/ in this word?

Reading on at Etymonline, the story is revealed. The <ch> is NOT etymological and was inserted in the late 16th century, “a pedantic imitation of a corrupt spelling of the Latin word.” So even though the <ch> in this word is NOT derived from the Greek letter chi, it now looks like and behaves like it was, including being pronounced /k/. The <h> is part of the <ch> digraph. It is not operating as an independent grapheme.

So what about architect, character, and chord? They each have <ch> representing /k/. Do they share a Hellenic ancestry? Well, architect is from the Greek αρχι-τέκτων “chief builder.” That would have been transcribed by the Romans as archi-tecton. As you will notice, the third Greek letter was χ (chi). When that letter was transcribed by the Romans, they transcribed it as <ch> and pronounced it /k/.

Digging into the etymology of character we find that it is from the Greek χαρακτήρ “engraved mark”. As you can see, the initial letter in Greek was again χ (chi). This word was transcribed by the Romans as character . The initial <ch> was pronounced /k/. This word lost that <ch> spelling for a while. At one point it was adopted and adapted by Old French and its spelling changed to caratere “feature, character”. It was sometime in the 1500’s that the <ch> spelling was restored.

So what about chord? Will we see that it too has a <ch> that derived from the Greek letter χ? Prepare for another interesting word story! This word has two entries. The first is as a noun meaning “two or more musical notes sounded together”, and is from 1608. It is an alteration of Middle English cord, a shortened form of accord. The second is as a noun meaning “a structure of the body, emotions figuratively considered as a string on a musical instrument, straight line connecting two points on a circumference”, and is from 1543. The note of interest is this statement in the Chambers Dictionary of Etymology: “English chord(2) and Latin chorda, both meaning a string of a musical instrument have influenced this word by association of form and meaning.” If the Latin word was chorda, that initial <ch> is like the others we encountered in character and architect. It was originally a χ (chi) in Greek. The Greek word was χορδή “a string of gut, the string or chord of a lyre or harp.”

So what about the claim that in the words anchor, architect, character, and chord the <h> is silent (unpronounced)? It is not. The <h> is part of the digraph <ch> that represents /k/ in these words. When you see this particular digraph representing /k/ in a word, it is usually marking a Hellenic heritage.

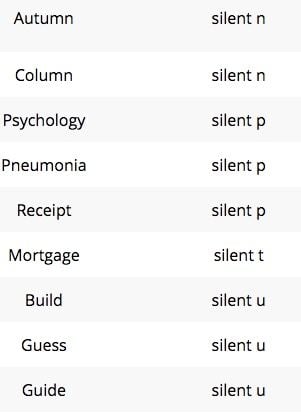

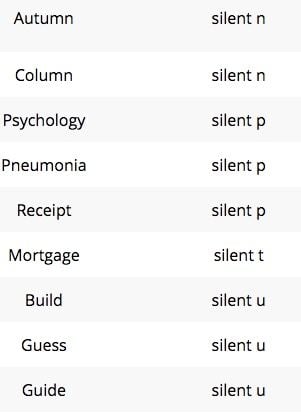

The words autumn and column have a final <n> that is not pronounced. Why? When we look at autumn we see it is from Latin autumnus. Minus the Latin suffix, the spelling is a direct derivation. Interesting side note: This season was called Harvest by the English until Autumn displaced it in the 16th century.

The word column is from Latin columna “pillar.” Again, the Modern English spelling is a direct derivation. The final <n>’s in these words may not be pronounced, but they are pronounced in other members of these word families. Think of autumnal, autumnally, columnist, columnar, columniation. We can think of the final <n> marking a connection to its relatives!

The word psychology takes us back to Greek. How do I know? Check out the <ch> grapheme representing the phoneme /k/! But with this word we are to focus on the initial <ps> cluster in this word. This word was coined in the 1650’s from a Latinized form of ψυχικός “breath, spirit, soul.” You see and recognize the third letter in, right? It’s χ (chi). It was transcribed by the Romans as <ch> since they didn’t have a letter that was its equal. Well, look at the first Greek letter in the same Greek word. It is the letter ψ (psi). When it was transcribed into Latin, the Romans had no equivalent letter, and so transcribed it as <ps>. In Modern English, this cluster is considered unpronounceable when it is initial in a word. We pronounce only the <s> in words like psychiatrist and psychedelic. Both the <p> and the <s> are pronounced though, in words like biopsy, autopsy, and epilepsy.

Next on the list is pneumonia, and the focus is on the initial unpronounced <p>. This word comes from the Greek word πνεύμων transcribed as pneumon “lung.” The reason we no longer pronounce the inital <p> is because of its placement. Richard Venezky (The American Way of Spelling) describes this cluster as unpronounceable when it is initial. When we see this cluster in another position, that is not the case. Look at apnea and tachypnea.

Now let’s look at receipt. The focus here is also the unpronounced <p>. This word is from Old French recete and before that from Latin recepta “received.” According to Chambers Dictionary of Etymology, “The English spelling with p (in imitation of the Latin form) is first recorded in the late 1300’s, but did not become the established form until the 1700’s.” So the <p> was in the spelling of the Latin word recepta, but disappeared as this word was adopted and adapted in Old French. It reappeared sometime in the late 1300’s, and became part of the established form of the word in the 1700’s. That explains its place in the word, but what about it not being pronounced? Well, according to Richard Venezky, there are a small group of “borrowings and scribal tamperings” in which the <p> is unpronounced. Besides receipt, examples include corps and coup.

With mortgage we’ll be looking at the unpronounced <t>. According to Etymonline, this word was first attested in the late 14th century as Old French morgage “conveyance of property as security for a loan or agreement.” This Old French word is from mort “dead” and gage “pledge”. This name is fitting because “the deal dies either when the debt is paid or when the payment fails.” Old French mort is from Latin mortuus. The <t> was not evident in the Old French word, but was restored in English based on the Latin. This word is considered a French borrowing with the <t> restored to mark an etymological connection to its Latin root mortuus. As such, the <t> is not pronounced.

The next three words have unpronounced <u>’s. The first is build. It is from Middle English bilden and earlier (probably 1200) it was bulden “dwelling.” According to Chambers, “It was not until the late 1500’s that our spelling begins to appear with frequency. Even so, the spelling is not accounted for, unless it is simply a composite of the two earlier spellings bilden and bulden.” The sense and meaning of putting something together came about in 1667. Although <u> is found in words like guild, guilt, guitar, and circuit, and therefore might appear to be a <ui> vowel digraph, it is not. The <u> has a specific function in those words that it is not performing in build. I will explain further in the next paragraph as we look at the words guess and guide. In the word build, the <u> is unpronounced.

The word guess is from Old English gessen “infer, perceive, find out.” According to Etymonline, the <gu> was late 16th century. This sometimes happened in Middle English to signal a “hard” pronunciation of the <g>. In this word, the unpronounced <u> is considered a marker letter. It marks the pronunciation of the <g>.

The last word in this group is guide. This word is from Old French guider “to lead, conduct.” The <u> has always been part of the spelling of this word. Here, the unpronounced <u> is considered a marker letter as it was in guess. It is marking the “hard” pronunciation of the <g>.

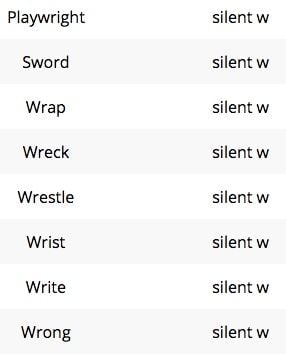

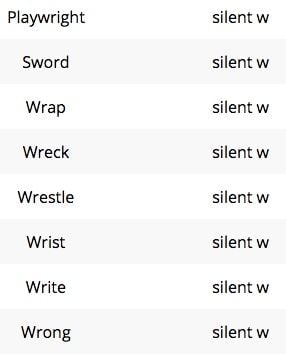

This last group of words are all listed as have a silent w. Let’s find out what we can about them.

First up is playwright. According to Wikipedia, “It appears to have been first used in a pejorative sense by Ben Jonson in 1853 to suggest a mere tradesman fashioning works for the theatre. Jonson described himself as a poet, not a playwright, since plays during that time were written in meter and so were regarded as the province of poets.” You see, at the time, the word wright was Old English wryhta, wrihta “worker.” Ben Jonson saw what he did as above the rank of a worker. He referred to himself as a poet and not a playwright.

As far as the <wr> spelling, Etymonline notes that it was a common Germanic consonantal combination (and that we can see for ourselves when we look at the Old English spelling). It is especially interesting to note that the <wr> combination often starts words that imply twisting or distortion. A worker or crafter might indeed need to twist in order to craft something! Etymonline goes on to note that the <w> ceased to be pronounced sometime c. 1450-1700.

The next word on the list is sword. This word is from Old English sweord, swyrd, sword “cutting weapon.” As you can see, the <w> has been part of its spelling since its beginning and was no doubt pronounced at that time. Even though that <w> is generally unpronounced in this word, we can consider the <w> as marking its language of origin.

Now let’s look at wrap. This word was first attested in the 14 c. as Old English wrappen “to wind something around something else.” This is the same common Germanic consonantal combination we saw in wright that starts words that imply twisting or distortion. To wind something is certainly to twist it!

Wreck was first attested in the early 13th century, “goods cast ashore after a shipwreck.” Before that it was from Anglo-French wrec and before that from a Scandinavian source. A note of interest here from Etymonline is that “wrack, wreck, rack, and wretch were utterly tangled in spelling and somewhat in sense in Middle and early modern English.” And, again we see that same Germanic consonant pair <wr> that can imply twisting or distortion when initial in a word!

I bet you already see the Germanic consonantal combination in wrestle and can see the implication of twisting and distortion in this word’s meaning. This word has a frequentative suffix <-le>, which means the action happens over and over. The base wrest is from Old English wræstan “to twist, wrench.” Once again, the <w> may no longer be pronounced, but it is marking that etymological connection to Old English and the <wr> combination here implies twisting and distortion.

Next up is wrist. I bet YOU could tell ME about that <w> this time! Yes, it IS from Old English. It was spelled wrist and the notion was “the turning joint.” In other words, the <w> is unpronounced and marks the etymological connection to its Old English roots and the <wr> combination here implies twisting and distortion.

Now let’s look at write. It is from Old English writan “to score, outline, draw the figure of.” Once again we have the <w> marking its connection to its language of origin, Old English, and that <wr> implying twisting and distortion.

The very last word on the list is wrong. Surely this word will have a different story to tell. Let’s see. It’s from late Old English “twisted, crooked, wry.” According to Etymonline, “the sense of not right, bad, immoral, or unjust was developed by c. 1300. Wrong thus is etymologically a negative of right, which is from Latin rectus, literally straight.” You will recognize the Latinate base <rect> in the word correct! As for the <w>? It functions just like the <w> in playwright, wrap, wreck, wrestle, wrist, and write. It marks the connection to the Old English heritage each word has. And when paired with <r> in words of Germanic heritage, an initial <wr> often implies a twisting and distortion of some sort.

Here’s a list of the words once more with an explanation for the unpronounced letter in each:

read … the <a> is part of the digraph <ea> and as such is not an independent letter in this word.

crumb … the <b> marks a connection to other members of the word family in which it is pronounced, such as crumble and crumbling.

debt … the <b> marks a connection to the word’s root and related words in which the <b> is pronounced, such as debit.

lamb, dumb … in Modern English, the <mb> is considered an unpronounceable cluster and as such the final letter is unpronounced.

ascend, scene, science … the <sc> represents /s/, so the <c> is part of a digraph.

Wednesday … the <d> followed by an <n> caused the <d> to be elided (unpronounced).

reign … the <g> is unpronounced but marks a meaning connection to a related base <regn>.

anchor, architect, character, chord … the <h> is part of the <ch> digraph representing /k/ which signals a Hellenic heritage.

autumn, column … the <n> marks a connection to other members of the word’s family in which it is pronounced, such as autumnal and columnist.

psychology … the <ps> marks a Hellenic heritage. When the <ps> is initial, the <p> is unpronounced.

pneumonia … when the <pn> cluster is initial, the <p> is unpronounced.

receipt … the <p> is unpronounced in this word as well as in corps. It is part of a small group of “borrowings and scribal tamperings” that have unpronounced letters.

mortgage … the <t> marks the historical language of origin (Latin) of <mort>.

build … the <u> is unpronounced and although there are ideas about the historical phonology, I could not find an agreed-upon explanation.

guess, guide … the <u> marks the “hard” pronunciation of the <g>.

sword … the <w> marks the language of origin (Old English) and a time when the <w> was pronounced.

playwright, wrap, wreck, wrestle, wrist, write, wrong … the <w> is part of the Germanic <wr> consonant cluster that implies twisting and distortion.

Labeling letters as silent is a problem.

The problem with calling a letter silent is that it feels like an explanation to someone who is learning to read. “Oh. Don’t worry about the <g> in sign. It’s a silent letter. Just skip over it.” That learner will probably become as complacent as the adults around him and not even look for an understanding as to WHY it is not pronounced in that word. And, of course, by just moving on, thinking there is no reason for it to be there, they will miss out on understanding a whole lot about digraphs, markers, etymology, word families, and phonology.

Just imagine what it would be like if letters COULD talk. What if they could each tell you their history or how pairing them up with other letters to form graphemes matters! What if they could tell you that their coming together in a spelling is like music and the melody each word creates is in their sense and meaning!

Until then, let’s speak on their behalf. Let’s not lump all unpronounced letters into one mislabeled group. Unpronounced does not mean uninteresting or without purpose. Let’s celebrate the history and individual awesomeness of each!

So what is the truth here? Are these letters silent? Sure they are. But then again, so is every other letter in the alphabet. A better attitude to instill in our young learners would be, “That letter isn’t pronounced? Well, it MUST be there for a reason. I wonder what it is? Do you want to help me find out?”