Spelling out words and building word sums is central to students really understanding about a word’s structure and its relationship to other words in its family. Last week I had the opportunity to enact a word sum with our K-5 staff at a staff meeting. For the first 30 minutes we were very fortunate to Zoom (like Skype) with Peter Bowers from WordWorks. He introduced activities to use with children of any age. These activities put the focus on recognizing when words belong to the same word family (share a base). Pete also talked about the importance of having students spell out words. By this he means that students announce each grapheme that represents a phoneme. As you watch the video below, listen to how the students do this.

The brilliant and valuable idea of having students enact building a word sum is Lyn Anderson’s. Her blog, Beyond the Word, is rich with activities that help students make sense of words and spellings.

Before I asked our staff to walk through building a word sum, I videotaped my 5th graders doing the same activity.

Once students understand the idea of building word sums, and how we can find other word family members by using different prefixes or adding different or sometimes additional suffixes, it’s time to encourage them to hypothesize about word structures.

The first step in any word investigation is to agree on the meaning of the word. Throughout our investigation, we will always be comparing our thoughts and hypotheses to our base word’s meaning. This is what we are referring to when we say that our hypothesized word sum must pass the meaning test.

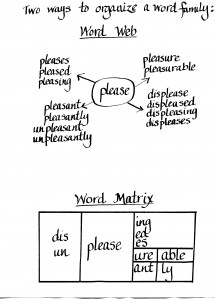

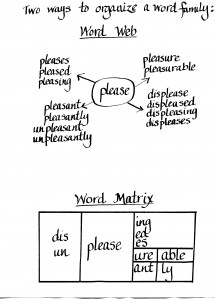

The second step is to ask ourselves, “What are its relatives?” Now we think of words related in meaning and spelling. In this case we can think of pleasing, pleases, pleased, displeased, displease, displeases, pleasant, pleasantly, unpleasant, unpleasantly, pleasure, and pleasurable.

Let’s look at the word ‘pleasurable’. When building the word sum for this, we talked in the video about “Checking the Joins” and needing to replace the single silent ‘e’ on the base ‘please’ when adding the vowel suffix ‘ure’. Then we talked about replacing the single silent ‘e’ on the suffix ‘ure’ when adding the vowel suffix ‘able’.

The next step is to write the word ‘pleasurable’ on the board and ask, “How is it built?” I want students to suggest a word sum hypothesis for it. At the beginning of the year, students think this means to break the word into syllables. As the year goes on, they begin to let go of that automatic response and to look for recognizable affixes instead. If your students are new to this kind of thinking, they might hypothesize that the word sum for ‘pleasurable’ is:

pleas + ur + able

ple + sur + a + ble (notice they are thinking syllables, not meaning)

pleas + urable

pleasur + able

I accept all hypotheses offered. Then I suggest that we look for evidence to prove that one hypothesis is more likely than any of the others.

First piece of evidence: Let’s look at the other words in this word family. We see ‘please’ and ‘displease’. Here is our first piece of evidence that there is a final single silent ‘e’ in ‘please’. It is also evidence that ‘ple’ and ‘pleasur’ will not be the base. (‘ple’ does not have a meaning and does not pass the meaning test.)

Second piece of evidence: Looking at ‘pleas’, one notices that it looks like the plural of the word ‘plea’. This is a great opportunity to revisit the role of a single silent ‘e’ in the final position of a word. Students know that a single silent ‘e’ can force the medial vowel to be long, as in ‘bike’. Here we can introduce another reason for the final single silent ‘e’ — so that a word doesn’t look plural when it isn’t. My students learned this when we investigated ‘condensation’ during a science chapter earlier this year. The word sum we agreed on is con + dense/ + ate/ + ion –> condensation. Without the ‘e’ on the base, ‘dens’ looks like the plural of ‘den’.

With that evidence, we conclude that the base of ‘pleasurable’ is ‘please’. Now we look at the rest of the word. Is ‘able’ a suffix? Our task is to find at least three words in which it is clearly the suffix. The three words could be bendable, taxable, and payable. Our next question is whether or not ‘ure’ is a suffix. Again we try to think of at least three words in which it is a clear suffix. Three words could be moisture, failure, and closure.

Putting all of that evidence together, the students are ready to alter their word sum hypothesis to read:

pleasurable –> please + ure + able.

There are several ways to organize and display a family of words. The following picture shows a word web and a word matrix.

By thinking of word families in this way, students have had the opportunity to think about suffixing rules and about logically collecting evidence to support their spelling choices. Students are actively involved as they build knowledge and understanding of English spelling.