When I sat down to lunch with my grade level team today, I was bubbling over with satisfaction after a rich and wonderful discussion that had just taken place in my room. I couldn’t help myself. I had to share what had just happened. I was too excited.

As I sometimes do, I wrote a word on the board and was asking the students to take a minute to think of what the word sum might be. I was looking for a hypothesis. From there we would see where the conversation went.

The word I began with today was <scientist>.

I made sure I gave time for the students to think about it. I have a few students whose hand shoots up automatically, and when I call on them, they need to pause to think of their response. You too? Then I also have a consistent core group of students who love to participate, and who, once they’ve thought about it, raise their hand in order to share. And then there are the rest of the students who watch and wait. They tend to keep their hands by their sides and their eyes looking down. I recognize that some are feeling unsure, but it is so important to participate in the discussion. Today I felt that this question could be asked of one of the students in this third group. I looked over the group and chose carefully. The student I called on thought for a moment and then suggested <sci + en + tist>.

Me: “That’s very interesting. Thank you for that. What do the rest of you think about Vanessa’s hypothesis? Is there a part of it that you have seen before in another word? Do you recognize any affixes you’ve seen before?”

Student: “I kind of think that it isn’t <tist>, but rather <ist> at the end.”

Me: “Can you think of another word with <ist> at the end? If we can, we will have collected some evidence that the <ist> is a suffix.”

One of the students who is usually reluctant to raise his hand, raised his hand. I called on him. He said, “Mist?”

Me: “Oooooo. Now that’s an interesting word. I want to come back to that word in a minute. Thank you for thinking of it.” I called on another student whose hand was raised.

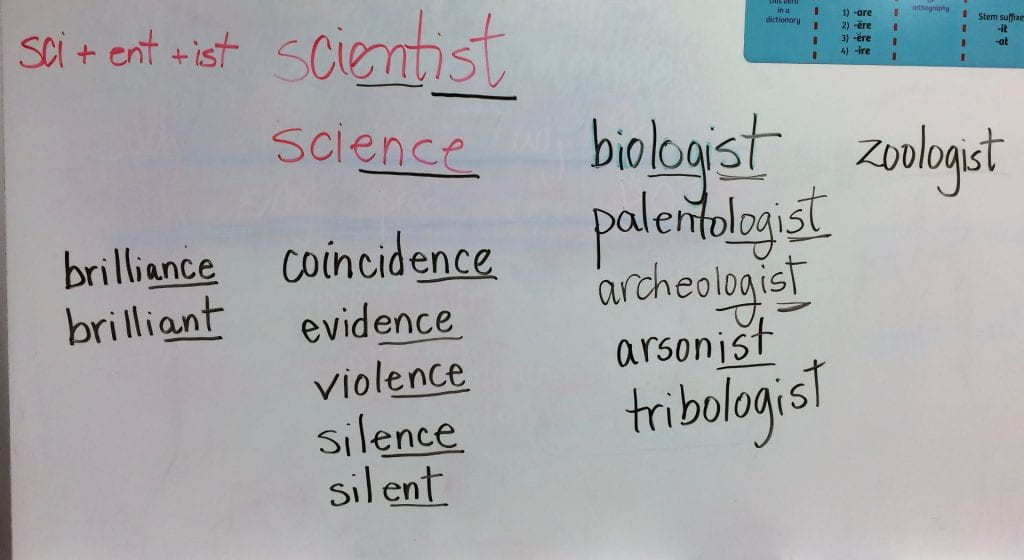

Student: “I was thinking of biologist. ”

As I was writing ‘biologist’ on the board, other words were being called out. I wrote them down as fast as I could. There was paleontologist, archeologist, arsonist, tribologist, and zoologist. And almost before I could finish writing the last word, a student blurted. “Hey! Almost all of them have an <log> before the <ist>!”

Me: “Brilliant! Scholars are people who notice things! Thank you for noticing that. Can anyone tell me what a biologist is?”

Student: “It’s someone who studies living things.”

Student: “And the <o>’s a connecting vowel, isn’t it?” (The student was referring to the <o> that follows the <bi> base. We had looked at ‘biosphere’ earlier in the year.)

Me: “It sure is!”

Student: “And isn’t a paleontologist someone who studies fossils?”

Me: “Yes. And an archeologist?”

Students said they heard of it, but no one knew what exactly an archeologist studied. So I told them that this person would be studying old times and ancient civilizations. At this point, a student who hadn’t previously joined the discussion raised his hand and said, “What’s an arsonist?”

The person who had suggested the word replied, “A person who starts fires.” There were a few confused by that. I could tell by their facial reactions. I went on to say that there are people fascinated by fire and they start fires to watch how the fire travels. Then I added that sometimes other people get hurt either fighting these fires or because they got caught in the fire. Arsonists usually get in trouble for starting fires.

When we were ready to look at the next word, at least three people spoke at once and explained that a tribologist was a person who studied rubbing things together. Yes, it’s true. About a week and a half ago, we watched a TED video about Jennifer Vail, a tribologist. She is really quite fascinating. Obviously the students thought so too because they suggested this word and remembered a lot about the video too! Click HERE for a link to the video in case you are intrigued.

Lastly, someone identified a zoologist as someone who studies animals.

Me: “I notice that all of these words have an <-ist> suffix, and they each refer to a person. We call that kind of suffix an agent suffix. There are others, but for today we are noticing this one, the <-ist> suffix.”

At this point I went back to the word <mist>. I asked if <mist> belonged on this list. I asked if it was referring to a person? The student who had suggested it, said that it did not fit. I followed up by saying that the <ist> in mist is like the <ing> in sing. Neither are suffixes. They are coincidences of spelling.

Me: “If the <-ist> suffix is the part of the word that tells us this word is referring to a person, which part of the word is telling us that the person studies something?”

Student: “The <log>?”

Me: “Excellent. So notice now that the biologist is the person who studies living things and the paleontologist is the person who studies fossils, but the arsonist is the person who starts the fire. It is NOT the person who studies fires. Right? There’s no <log> in that word. And so the scientist is the person who does the science just like an artist is the person who does the art! <Loge> is a bound base with a denotation of “science of.” We usually think of it having to do with studying the science of something. That makes every word up here with <log> in it a compound word! Awesome thinking everyone! Now let’s get back to the word we started looking at, <scientist>. We’ve figured out that the <-ist> is a suffix. What are your thoughts about the rest of the word?”

Student: “Well, I’m thinking about <science> and wondering if what happens is that when the <-ist> suffix is added to <scient>, the <t> changes to <ce>?”

Me: “Interesting. The suffixing changes I have seen are a final consonant being doubled, a <y> changing to an <i>, and a single, final, non-syllabic <e> being replaced. I haven’t ever seen a change like you are describing. Could it be that <ent> and <ence> are both suffixes and are used to get two forms of the word? Can anyone think of a word with an <ence> suffix?”

Student: “Coincidence! You just said that the <ist> in <mist> was a coincidence of spelling!”

Me: “So I did. Can anyone think of another word? The more words we can think of the more evidence we have.”

Student: “Evidence. You just said the word evidence!”

Me: “That is so funny. I surely did!”

Student: “How about violence?”

Student: “How about brilliance?”

Student: “Brilliance is spelled with an <-ance>.”

Me: “Right. Brilliance does have an <-ance>. I’ll write it to the side in case we think of more like that.”

Student: “And silence.”

And then it dawned on me. And I pointed out that we can switch out the <-ence> suffix in ‘coincidence’ for <-ent> and make the word ‘coincidental’. We can switch out the <-ence> suffix in ‘evidence’ with the <-ent> suffix and make the word ‘evidently’. At this point the students began to anticipate that ‘violence’ could be ‘violent’ and ‘silence’ could be ‘silent’. So we decided that the suffixes <-ence> and <-ent> can work with the same base. And of course we thought about <-ance> and <-ant> having the same kind of relationship.

Student: “Could it be that these suffixes are different forms of the same suffix, kind of like the assimilated prefixes we are studying?”

Me: “That’s something to think about, isn’t it?”

I will admit that the last question put the biggest smile on my face. I love that the students are making connections to what else they are learning about English spelling. I love that they are asking questions and getting caught up in these classroom discussions. It was so much fun! I’m beginning to recognize that from February to June is my favorite time of the year. This is when the pieces start to fit together and the understandings start falling into place. The students start having words on their minds all the time. Here is a picture of the board. You will recognize how everything ended up where it did from my description above. You may also recognize that I misspelled paleontology. I didn’t notice that until tonight when I was looking back at the picture.

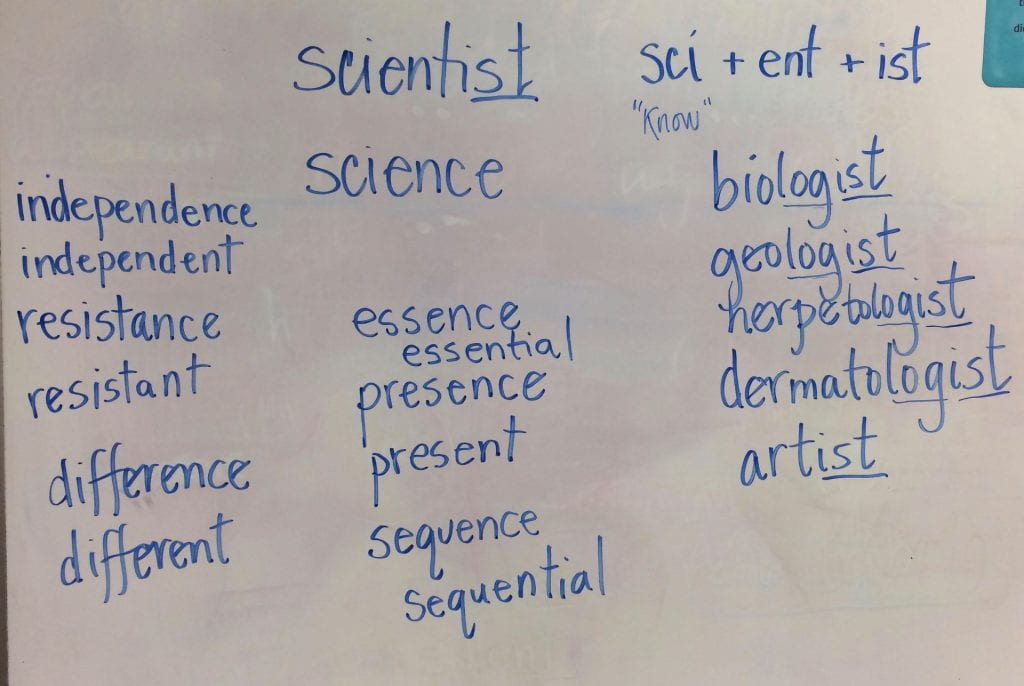

All of the above happened with the second class I see during my day. There was one more group to come in. They needed to take this journey for themselves, so I erased the board and started all over. Different words were suggested, but the ending observations were the same.

Now I want to take you back to my lunchtime discussion with my grade level colleagues. As I was going on about what the students were thinking of and what we were noticing as a class, I could tell that it was one of those times “you had to be there.” They weren’t feeling as excited as I was. They listened and followed along, but didn’t get why this was such a big deal for me. And then one of them said something that explained her perspective to me perfectly. She said, “That’s just it. If some words can have an <-ence> and some can have an <-ance>, how will our struggling spellers know which one to use? What can you tell them so they know which one to use?”

She is used to false rules that focus on what is on the surface of a word without having to really know much about the word. I told her that we would need to know more about the word’s etymology to know which to use. In the meantime, the understanding gained today will help if, for example, the student can spell ‘silent’, and want to spell ‘silence.’ Instead of phonetically spelling it as *silints (which they may do anyway – phonics runs deep), they have a chance of knowing that it will have an <-ence> suffix. I have no magic fix-it fairy dust. I just keep letting students see for themselves what is really happening in spelling and how consistent it is. Progress comes more slowly than others would like, but that is because instead of “know this by Friday for the test”, I am not telling students what to know. I let them see for themselves. I give them time to let things sink in. We revisit concepts often and hope that much of the understandings they develop here, will be theirs for life.

I can hardly wait for tomorrow so I can take the discussion in this same direction with my first group. We talked about some of these things this morning, but we didn’t take it in this direction. I’d like to see what words they think of, and if they recognize for themselves what the other students recognized today. Below is a picture of the board from the discussion I had with my last group of the day. I love looking at this and knowing that between the three classes, we collect a lot of evidence to support what we understand about spelling. That much is evident. 🙂