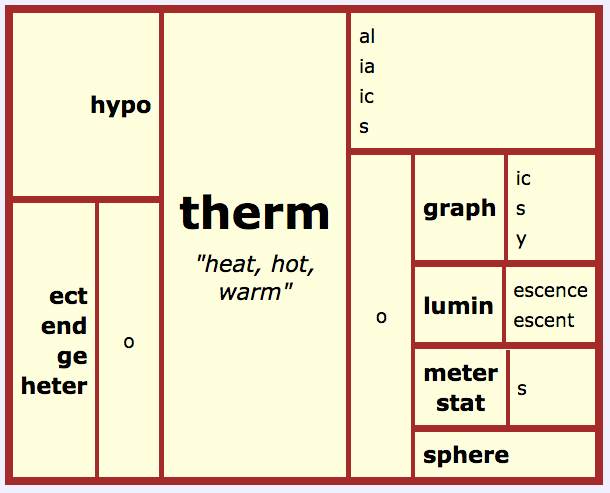

I came across an article at Science Friday called “The Origin of the Word ‘Thermometer’.” Since a recent post focused on the base <therm> “heat”, I was interested in seeing what this article said. It is a pretty interesting article, but I have one big question. What do I question, you ask? Here is an excerpt:

“The term is a compound word consisting of a Greek root and a French suffix, also of Greek origin. The ancient Greek word θέρμη, or therme, means heat, and θερμός (thermos) means hot, glowing, or boiling. The second part of the word, meter, comes from the French -mètre (which has its roots in the post-classical Latin: -meter, -metrum and the ancient Greek, -μέτρον, or metron, which means to measure something, such as a length, weight, or width).”

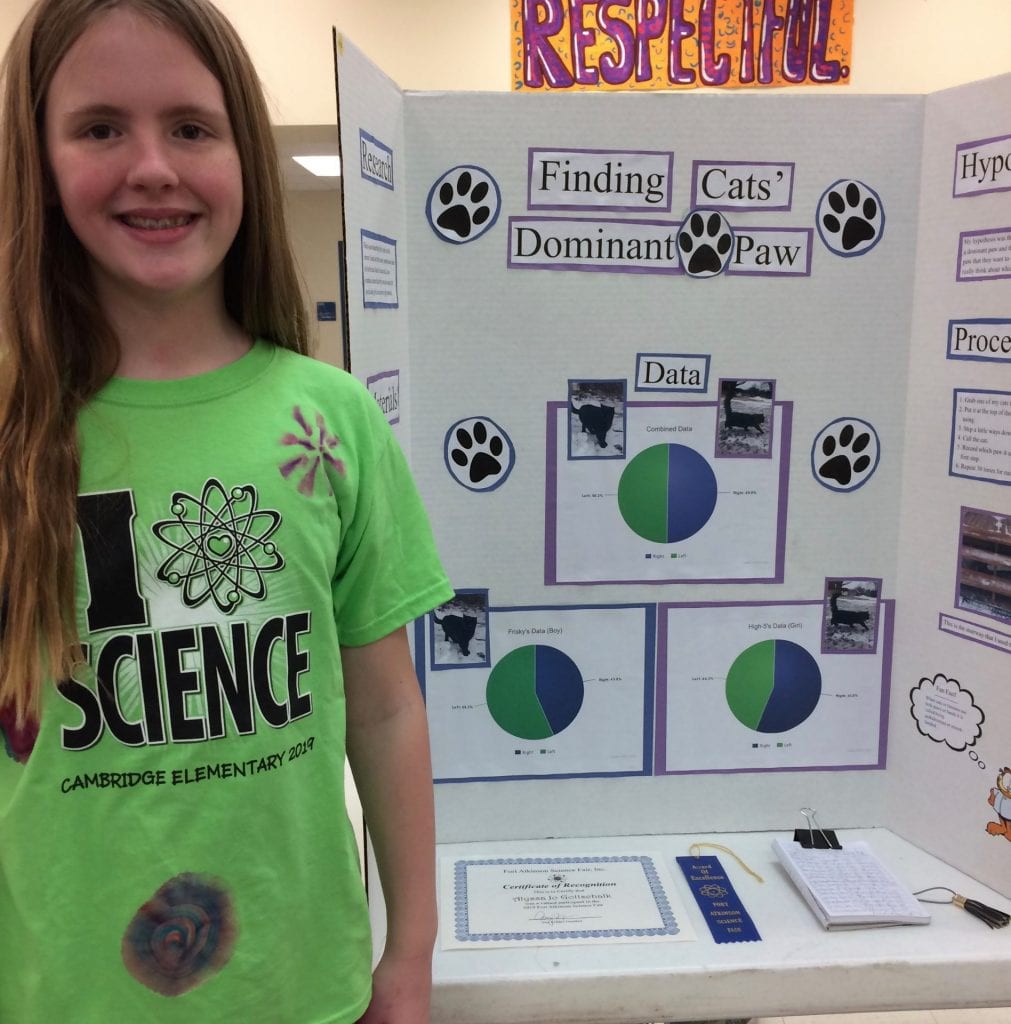

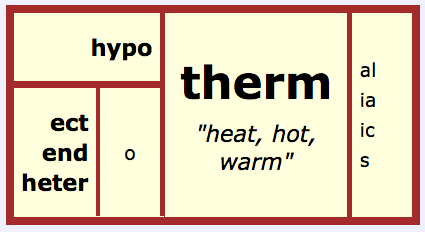

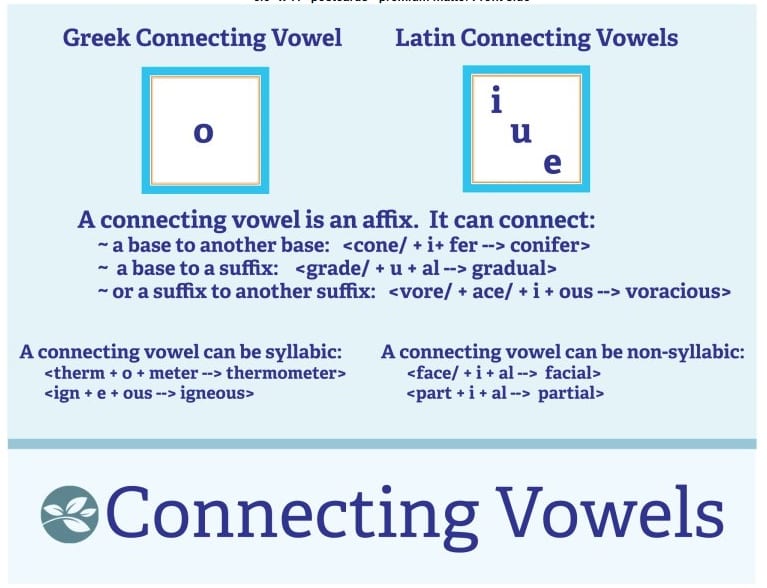

I’m aware that this word was coined in French, but it’s a bit confusing that the author both calls the word <thermometer> a compound word and then also says it consists of a Greek root and a French suffix. By definition, a compound word is a word that consists of two or more bases. It can’t be defined as a single base plus a suffix. If the author is suggesting that <metre> was a suffix in French, that is curious as well. All of the rest of the information in this paragraph jives with what I found at Etymonline and in my Liddell and Scott Greek Lexicon. The structure of <thermometer> is <therm + o + meter –> thermometer>. See? Two bases joined with the Greek connecting vowel <o>.

“In 1626, the French Jesuit Jean Leurechon (1591-1670) first coined the word “thermometer.” It appeared in his best-selling book, Récréation Mathématique, which he wrote under the nom de plume of Hendrik van Etten.”

This is where the article gets doubly interesting. The author shares some pages from Leurechon’s book. And that is when I am taken back to my high school senior class trip to Washington D.C.

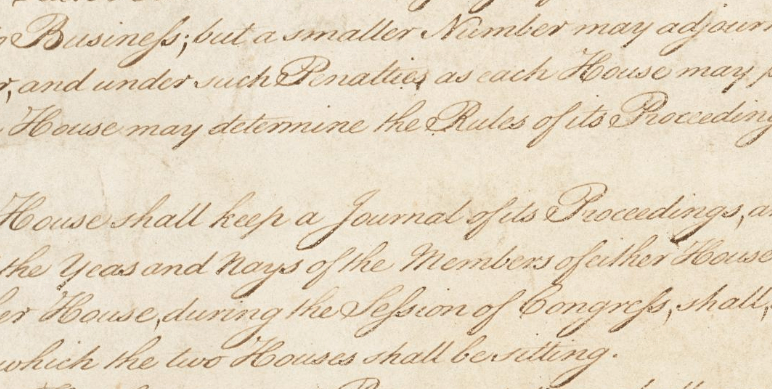

Without a doubt, the most memorable museum moment was seeing historical documents such as the The Constitution of the United States. I was drawn in by the beautiful penmanship. Once drawn in though, I couldn’t help but notice what seemed to be misspellings. Surely that couldn’t be the case. At the time this was written, did they really spell Blessings as “Blefsings?, business as “businefs”, session as “sefsion”, and Congress as “Congrefs?” I looked around at other words with <s> and the only place this “f” was used was when there would be two <s>’s in a row. I thought it was so cool. I just accepted that for whatever reason, that was the convention of the time (1787). It wouldn’t be until 30+ years later that I would learn more about that interesting convention. I found this excerpt at The National Archives Catalog . The first word in the top left looks like “Businefs.” In the second line from the bottom you can see what looks like “Sefsion of Congrefs.”

What I know now is that it wasn’t an <f> at all, even though the resemblance is still striking. It is a long <s>. By the looks of its use in the Constitution, it was already losing its grip and falling from use in 1787. So I bet you knew that an <s> could be big (as in capitalized) or small (as in lower case). But did you know that there once existed a long <s> in addition to a short <s>?

This long <s> was derived from the old Roman cursive <s>. Here is a image from the Creative Commons files at Wikipedia:

Towards the end of the 8th Century, the distinction between majuscule (what we think of as uppercase letters) and minuscule (what we think of as lowercase letters) resulted in the above symbol becoming a bit more vertical. By the 12th century, the <ſ> was used at the beginning (initially) and in the middle of words, and <s> was used and the end of words (finally). Below is an example of the long <s> in print. You probably notice that the long <s> looks quite like an <f>. But a more careful look helps you notice that what looks like the crossbar doesn’t actually cross the down stroke. It is just a nib on the left. Compare that to the <f> in the sample below.

Here you can see the slight but significant difference between an <f> and a long <s>.

Sometimes it was written without the left side nub. When the long <s> was written in italics, it looked different again:

As you look at examples of the long <s> in use, you may notice variations in how the long <s> was presented, but you will no doubt recognize it just the same. Because the italicized version curved to the left, and that made for some spacing problems when setting the type, both the long and short forms of <s> were used in combination. Just in case you’ve had the opportunity to study the Greek alphabet, I’m including information from Wikipedia regarding the two forms of the letter sigma (which would be transcribed as <s>) there too.

“Greek sigma also features an initial/medial σ and a final ς, which may have supported the idea of such specialized s forms. In Renaissance Europe a significant fraction of the literate class was familiar with Ancient Greek.”

I was familiar with the fact that one form of sigma was used if the sigma was initial or medial in a word and the other form was used when the sigma was final. If you are looking for a word in a Greek Lexicon such as Liddell and Short, this information is certainly valuable! The cool thing is that I never connected the Greek letter and its need for two forms with the English letter <s> and its need for two forms!

Here is a beautiful example of such a Greek word: σχολαστικός . The first letter is the initial sigma. The second letter is chi which is transcribed as <ch>. That is followed by omicron <o>, lambda <l>, alpha <a>, sigma <s>, tau <t>, iota <i>, kappa <k>, omicron <o>, and sigma <s>. Note that the final sigma <s> takes a different form than the initial and medial sigma <s>. If you’ve been following along and putting the transcribed letters together, you’ve no doubt spelled scholastikos. The denotation of this word is “devoting all one’s leisure to learning.” The Greeks knew that learning was something to be done leisurely in one’s leisure time!

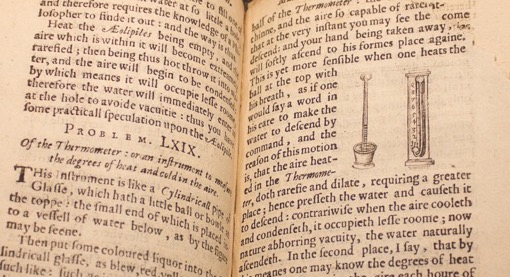

Now I direct your attention back to the article I read about the origin of the word ‘thermometer.’ This is a photo from the book written by Jean Leurechon.

The first use of the word ‘thermometer.’ Photo by Daniel Peterschmidt, courtesy of the NYPL Rare Book Division.

This 1626 book is the first time the word <thermometer> was seen in print! It is difficult to read the left side page, but I will rewrite what is on the right hand side starting with the sixth line from the top:

“This is yet more ſenſible when one heats the ball at the top with his breath, as if one would ſay a word in his eare to make the water to deſcend by command, and the reaſon of this motion is that the aire heated in the Thermometer, doth rarefie and dilate, requiring a greater place; hence preſſeth the water and cauſeth it to deſcend; contrariwiſe when the aire cooleth and condenſeth, it occupieth leſſe roome; now nature abhorring vacuity, the water naturally aſcendeth. In the ſecond place, I ſay, that by …..”

Now that you have a bit of understanding about the two forms of <s> used, what did you notice? Did you see both forms? I noticed that the long <s> was used initially (ſenſible) and medially (reaſon). I also noticed it was used twice in a row (leſſe). I noticed that the short <s> was used when a final <s> was needed (this, is).

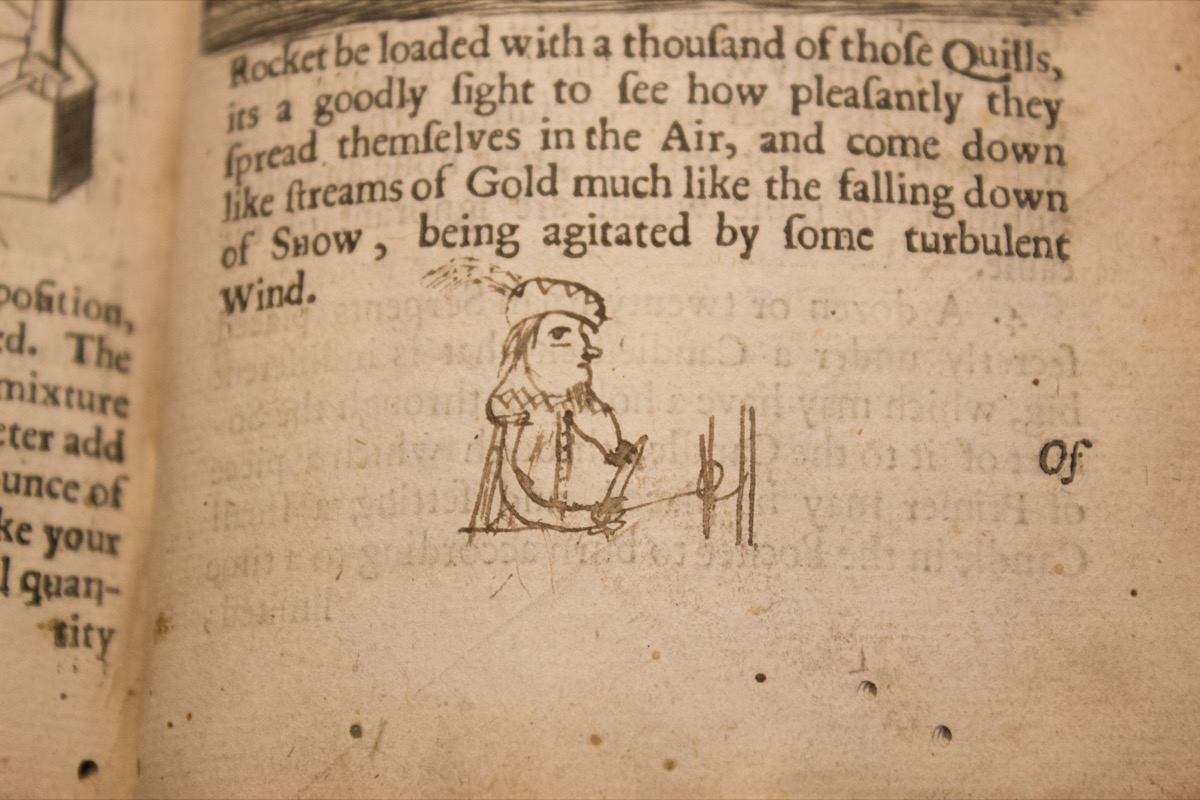

Let’s look at some more pages from an 1674 edition of the same book.

Photo by Daniel Peterschmidt, courtesy of the NYPL Rare Book Division.

This is from a page with directions on how to make rockets. You can probably read it for yourself this time. In what ways is the use of the long <s> the same as in the earlier book? Pretty much the same, right? The one difference I see is when the short <s> is used initially in the word ‘Snow’. I’m not sure why the <s> is uppercase in that word, but I bet that’s the reason the short <s> is used there instead of the long <s>.

So, interesting, isn’t it? There are actually lists of rules for when to use each form. I easily found this list at several sites. Here’s one from Colonial Sense, the website for all things colonial. These rules were applied “in books in English, Welsh, and other languages published in England, Ireland, Scotland, and other English-speaking countries during the 17th and 18th centuries.”

- short s is used at the end of a word (e.g. his, complains, succeſs)

- short s is used before an apostrophe (e.g. clos’d, us’d)

- short s is used before the letter ‘f’ (e.g. ſatisfaction, misfortune, transfuſe, transfix, transfer, succeſsful)

- short s is used after the letter ‘f’ (e.g. offset), although not if the word is hyphenated (e.g. off-ſet)

- short s is used before the letter ‘b’ in books published during the 17th century and the first half of the 18th century (e.g. husband, Shaftsbury), but long s is used in books published during the second half of the 18th century (e.g. huſband, Shaftſbury)

- short s is used before the letter ‘k’ in books published during the 17th century and the first half of the 18th century (e.g. skin, ask, risk, masked), but long s is used in books published during the second half of the 18th century (e.g. ſkin, aſk, riſk, maſked)

- Compound words with the first element ending in double s and the second element beginning with s are normally and correctly written with a dividing hyphen (e.g. Croſs-ſtitch, Croſs-ſtaff), but very occasionally may be wriiten as a single word, in which case the middle letter ‘s’ is written short (e.g. Croſsſtitch, croſsſtaff).

- long s is used initially and medially except for the exceptions noted above (e.g. ſong, uſe, preſs, ſubſtitute)

- long s is used before a hyphen at a line break (e.g. neceſ-ſary, pleaſ-ed), even when it would normally be a short s (e.g. Shaftſ-bury and huſband in a book where Shaftsbury and husband are normal), although exceptions do occur (e.g. Mansfield)

- short s is used before a hyphen in compound words with the first element ending in the letter ‘s’ (e.g. croſs-piece, croſs-examination, Preſswork, bird’s-neſt)

- long s is maintained in abbreviations such as ſ. for ſubſtantive, and Geneſ. for Geneſis (this rule means that it is practically impossible to implement fully correct automatic contextual substitution of long s at the font level)

Wikipedia explains the decline in the use of long <s> like this:

“In general, the long s fell out of use in Roman and italic typefaces in professional printing well before the middle of the 19th century. It rarely appears in good quality London printing after 1800, though it lingers provincially until 1824, and is found in handwriting into the second half of the nineteenth century.”

In my search for more information about the long <s>, I came across this website: The “ſociety for the Reſtoration of the ſ.” I was suspicious at first, wondering if this society was a real thing or not. But as I read through the page and enjoyed the examples from old books, I became a fan of the <ſ> and of a society that would try to preserve it. I was ready to join! But then I saw this small print at the very bottom just before the comments. I was not surprised, although I will admit there was a twinge of disappointment that I could not actually join this group:

“This entry was posted in Collections and tagged April Fools’ Day, history of printing, long s, Society for the Restoration of the Long S, typography by nyamhistorymed. “

All in all, the <s> grapheme has a pretty interesting history. Makes one wonder what the rest of its story is. Makes one realize that if <s> has such an interesting history, perhaps every one of our letters has an interesting history as well! Hmmmm. What a delicious idea!