I came across this article today and the title drew me in: “Is this the most powerful word in the English language?”

When I realized the article was focused on the word ‘the’, I smiled. Putting aside whether or not it is in fact the most powerful word, we can all agree that it is certainly common. While it is not difficult to write a single sentence without this word in it, you’re not likely to find an entire paragraph without its use. In this article the author makes a great point, “While primary school children are taught to use ‘wow’ words, choosing ‘exclaimed’ rather than ‘said’, he doesn’t think any word has more or less ‘wow’ factor than any other; it all depends on how it’s used.” The ‘he’ referred to in this quote is Michael Rosen, poet and author.

I’m sharing this particular quote because I couldn’t agree more. While it feels right to bring to a student’s attention words like benevolent, pterodactyl, photographic, and emancipation, it is also right to bring to their attention words they already know how to spell, pronounce, and use. But that is less likely, isn’t it? There seems to be this driving task behind the teaching of reading: Teach all the words. Once the child “knows” a word, move on to the next. And how do we as teachers quickly judge whether a child “knows” a word or not? Speaking for myself, I used to question words that they couldn’t pronounce far more often than a word they could pronounce. I figured that if they couldn’t pronounce it, perhaps they were unfamiliar with it and then also didn’t know its meaning. And that might well be the case in many situations. It didn’t mean I shouldn’t question the words they pronounced smoothly, but since students at a fifth grade level can pronounce so many words, it is difficult to wonder which of those they don’t know the meaning of. (This is one of my personal struggles with frequent fluency tests and phonics teaching outside of the context of a word. I see where being fluent is needed, but because it is easy to test, we tend to do it a lot. And that sends the message to the students that speed is a sign of a great reader which we all know is not necessarily true.) When you pair fluency up with pronunciation before the sense and meaning of the word has been established and understood, we end up with students who read well, but comprehend poorly. My concern is that we pass along another unintended message about what is important to our students.

It’s probably impossible to rid oneself completely of teaching things you don’t intend. But if you are constantly aware of what you are teaching and the manner in which you are doing it, if you are constantly reflecting on whether or not that manner is the most effective way, and if you are constantly comparing what the students understand to what you intended them to understand, you stand a better chance of recognizing those unintended messages and doing something about them. It is another reason I wish we could do away with one-size-fits-all reading/writing/vocabulary programs and instead teach our educators how the English language works. When a teacher comes to rely on a manual for “right and wrong,” too many stop seeking answers to questions that come up. The assumption is that if there were answers, they would be in the teacher manual. But they aren’t. Imagine having Structured Word Inquiry as a college requirement! We could then give students the opportunity to address the questions they have about English spelling, and teach them how to go about investigating their questions.

What specifically do most educators teach a child about a specific word? Well, I think it depends on the word. With the words ‘benevolent’, ‘pterodactyl’, ‘photographic’, and ’emancipation’, most would teach pronunciation, spelling, and meaning, either generally speaking or in the context of where the word was noticed. With the words ‘the’, ‘because’, ‘of’, and ‘their’, most would teach pronunciation, spelling, and point out their use in sentences (teaching meaning is not as clear-cut with function words).

The above paragraph describes teachers who are given a program to use and decide what is important for students to know about a word based on what they remember about their own learning of spelling. Teachers who incorporate the Four Questions of Structured Word Inquiry into their word study also bring in awareness of morphology and etymology to explain a word’s story and spelling. I’m not being judgy here, I just know how ill equipped I was before I found SWI. I believed I was giving them everything they needed. Wait. That’s not true. I knew I wasn’t helping them understand a word’s spelling, but I didn’t know how to fix that. I didn’t know where to learn more. When you’re handed a teacher manual, you assume it has everything you need to teach, explain, and understand spelling. Hardly.

Function and Content/Lexical Words

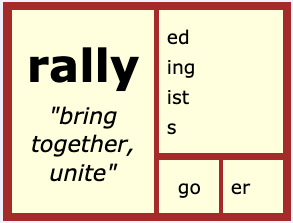

The list of shorter words I’ve mentioned are called function words. Few students are taught about function words and lexical/content words. The more you know about why words are categorized this way, the more sense it makes to share that information with children. The following video gives you some basic information about these two categories. I would add that some words (adverbs for example) are less accurately placed specifically in one of these categories and more accurately placed on a spectrum that lists content words at one end and function words at the other. In other words, depending on context, a word might be functioning more as a content word or more as a function word. The other great point this video makes is that we reduce the stress on function words far more often than we reduce the stress on content words in speech. Explaining that to children would help them understand why they misspell those words when writing down sentences instead of words in isolation. It isn’t that the word is difficult, it’s what happens to the word when we speak as we do in our stress-timed language.

Another recognizable quality of content or lexical words is that they have at least three letters. That helps you understand the difference between ‘in’ (in the box) and ‘inn’ (a place to stay for the night). Think of the words ‘be’ and ‘bee.’ Which is easier to define in isolation? I bet you’ve answered ‘bee.’ That’s because it’s a content or lexical word. The function word ‘be’ is more difficult to define on its own because we don’t use it that way (on its own). It has a function in the sentence. Like the analogy the man used in the video, the function words kind of “hold up” the content words. In the sentence, “It’s going to be raining soon,” the word ‘be’ is reduced and is definitely “supporting” the content word ‘raining.’ If you can’t hear yourself put more stress (emphasis) on ‘raining’ than you do on ‘be,’ write down the sentence and ask someone else to read it. It might be easier to spot that way. Of course the fun of speaking a stress timed language is that you can move the stress in the sentence to emphasize different words and change the meaning of the sentence. That sentence could also have the stress on ‘soon’ (but it still wouldn’t be on ‘be.’

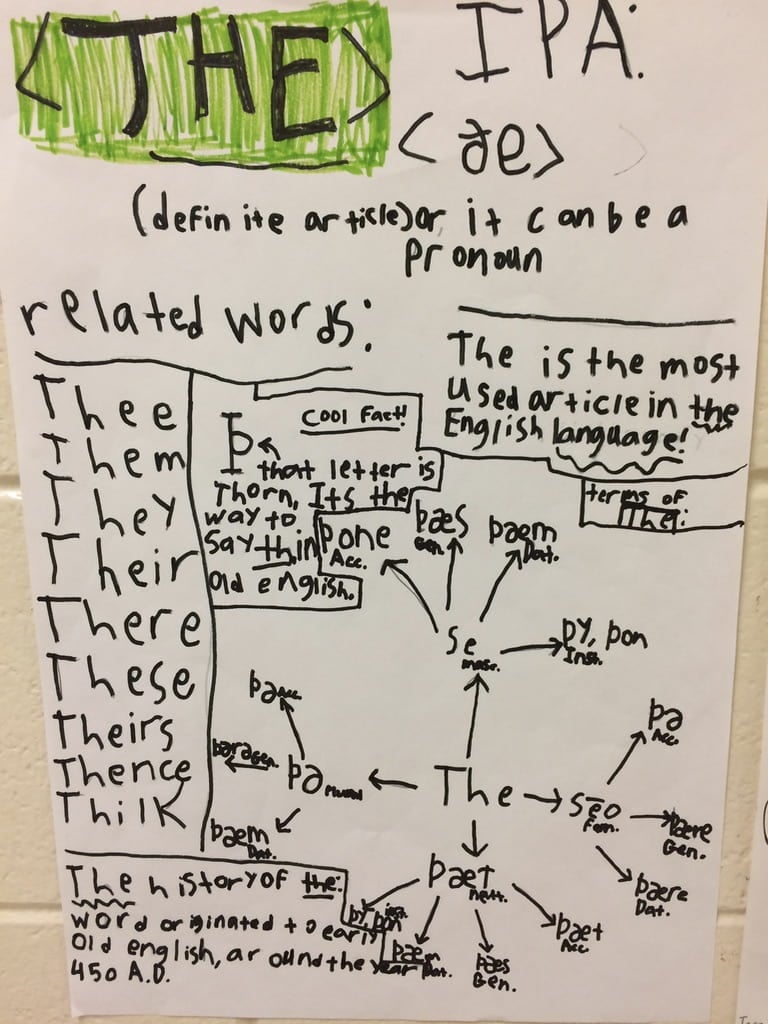

Every year, once my students have become familiar with using the Four Questions of Structured Word Inquiry, I ask them to choose any word to investigate. I’ve had students who chose a favorite food (bacon, cheese), a favorite animal (hippopotamus, octopus), a favorite object (amethyst, tractor), a random word from a book they were reading (perfidiousness, mission), and even their own name (Sawyer, Jade). But not until this year did I have a student who chose a function word! And guess which one he chose … you guessed it! The.

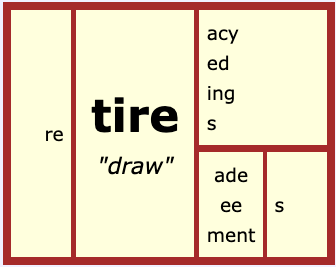

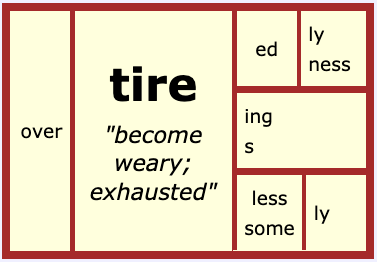

He was so surprised that there was this much information about such a short word! He and I discussed the Old English letter thorn (þ) that he saw in the Old English spellings in the entry at Etymonline. The chart in the entry is something this student recreated in his poster. He was a bit familiar with the earlier spellings of se (masculine), seo (feminine), þæt (neutral), and þa (plural) because we had watched the following video in which we learned the Old English names for common animals.

The first thing the author of this video does is explain why we will see different spellings for the early Old English spelling of ‘the.’ Here is a screen shot of that information as the author lays it out:

The spelling of <þe> replaced these forms in late Old English (after c.950). Old English had ten different words for ‘the’, but since there was no distinction between ‘the’ and ‘that’, both senses were embedded in those ten.

Reading further at Etymonline, I found out that ‘she’ probably evolved from the feminine form of ‘the’, sēo. The Old English word for ‘she’ was heo or hio, but there was a convergence of ‘he‘ and ‘heo‘ in pronunciation, and by 1530 ‘she’ and ‘he’ were separate words. We still see the original <h> in the word ‘her.’ (As I was checking out other resources for this post, I saw at the Oxford English Dictionary that there is another theory about how ‘she’ got its spelling. Check it out if you are able.)

Looking back at the boy’s poster, it is interesting to see the consistent <the> spelling of each related word with the exception of ‘thilk.’ This word is interesting because it was a contraction of the words ‘the’ and ‘same.’ So it was þe “the” plus ilce “same.” Several resources I looked at listed this word as archaic, so I went to the Oxford English Dictionary. It was first attested in 1225 and the most recent example they had of this word in use was in 1909. It had a sense of “this same one” or “the same.” I also googled the word to see if it would come up in any modern context. No such luck. In fact, Google assumed I was spelling the word incorrectly. That was more evidence that this word is not used much any more.

Because we study grammar in my classroom, the student knew that ‘the’ is an article, a definite article determiner. That definiteness is important in the comprehension of a thought. For instance, if I say, “Sing me the song,” you and I both know what song I am referring to. There is a definite song I want you to sing. If instead, I said, “Sing me a song,” I would be using the indefinite article ‘a’ and neither of us would have a specific song in mind. In fact, you might ask me what I’d like you to sing!

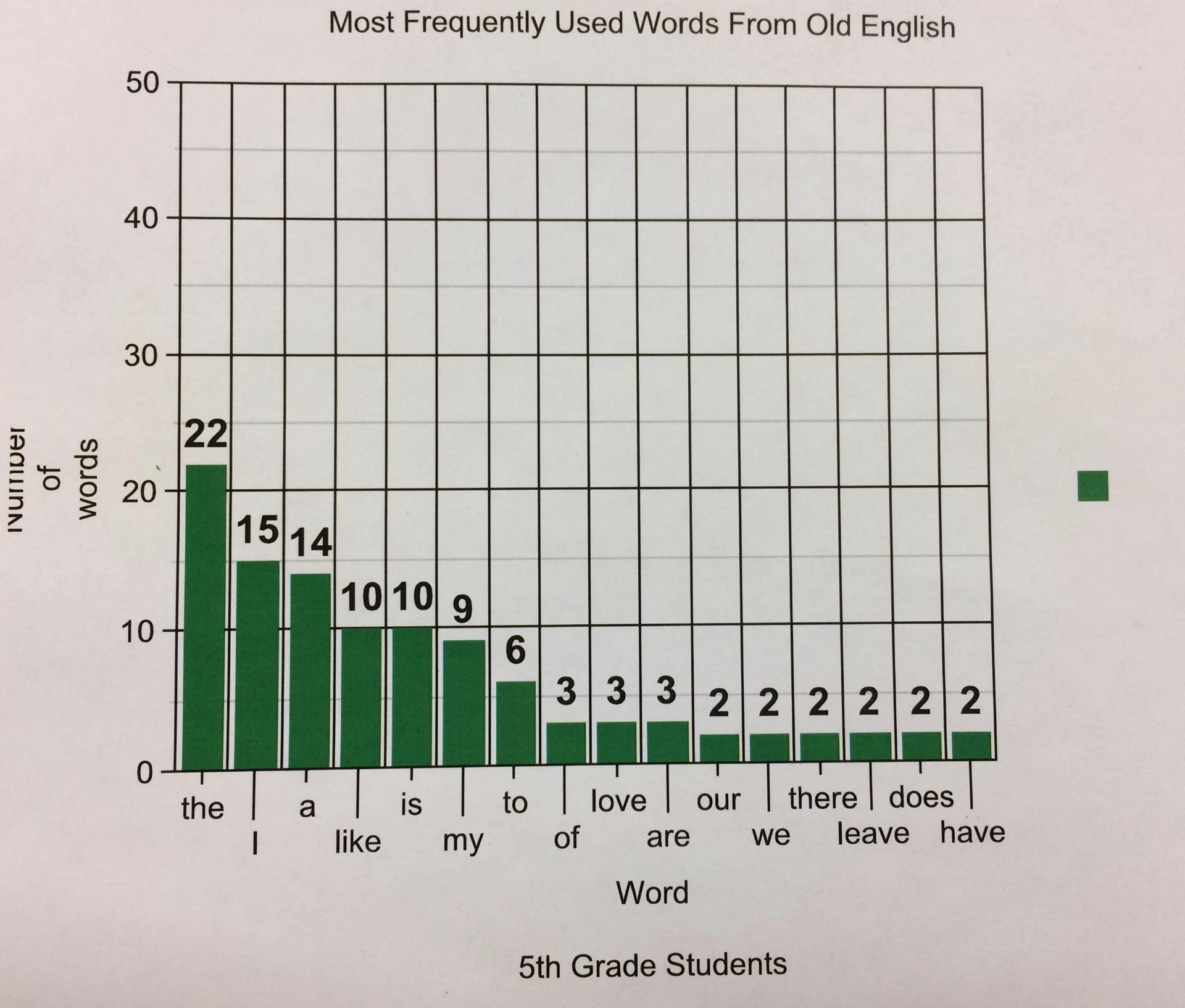

Last fall my students each wrote a sentence so we could investigate and identify the origin language of each word. We were trying to see if there was one ancestor more common to most of the words we use day to day. It was the second year I lead the students in this activity. If you are interested, you can read the blog post about it from January 2019: “History Is Who We Are And Why We Are The Way We Are” — David McCullough An interesting side piece of data that we collected showed how often we used certain words in common speech. The students wrote 49 sentences, and then we tallied how often we saw each word in those sentences. Here are the results for the most commonly used words:

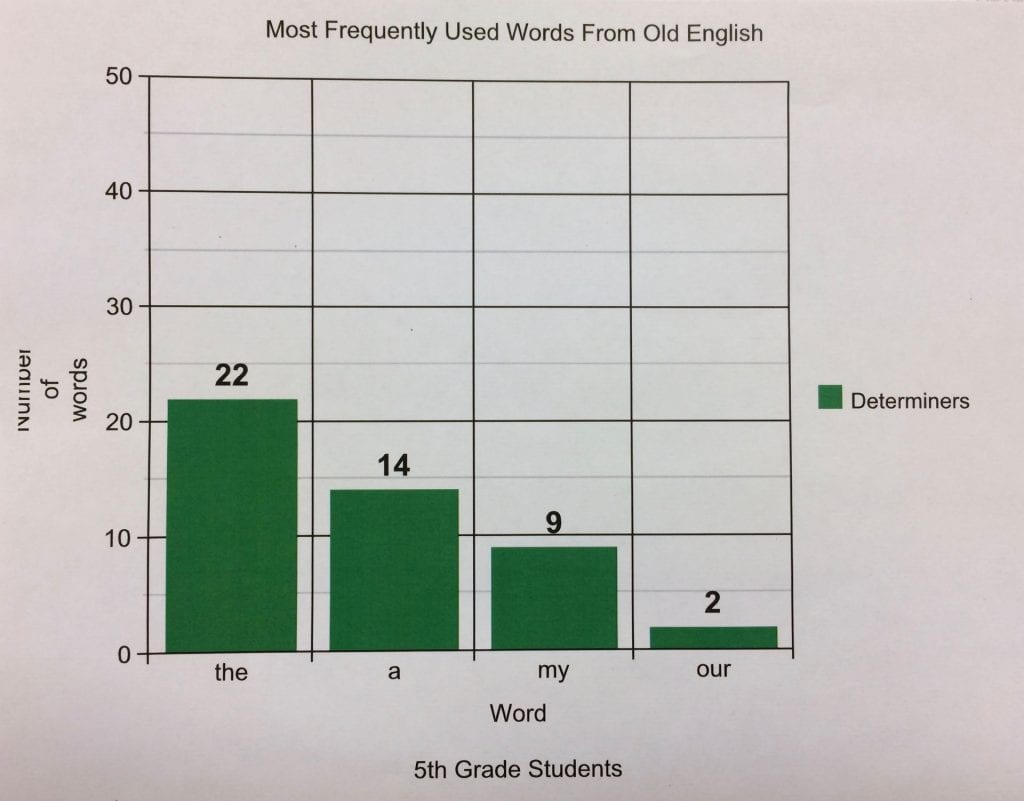

As you can see, ‘the’ was used 22 times! And of the 16 words that were used more than once, 11 were function words. I didn’t count ‘like’ as a function word, but depending on its use, it certainly could be. Remember when I said earlier that function and content words work better on a continuum than on distinct lists? The word ‘like’ illustrates that beautifully. Depending on its use, it can be a preposition, conjunction, noun, adjective, or an adverb. If it is used as a preposition or conjunction, it will be placed on the function word side. If it is used as a noun or adjective, it will be placed on the content word side. Here’s another graph of the function words that are specifically determiners:

What we notice here is that the article determiners were more commonly used than the possessive determiners. That wasn’t surprising considering what we’ve noticed in our study of grammar. Article determiners are the most common type of determiners. In case you are not familiar with determiners, they announce nouns. They are generally found in front of the noun they are announcing, but not necessarily immediately in front of the noun. In the case of “my shoe,” the possessive determiner is ‘my,’ and is immediately in front of the noun it is modifying. In the case of “every small chance,” the quantifier determiner is ‘every.’ It determines or announces the noun ‘chance’ and is in front of the adjective that also modifies the noun ‘chance.’

I think the importance of this data collection was the recognition that function words are indeed the foundation in our sentences. They are there to point our attention to the content words. The other fascinating thing was what the students noticed about the spelling of the function words. Words like ‘in’, ‘to’, ‘we’, and ‘an’ have had the same spelling since they were used in Old English. In looking at so many other words whose spelling changed over the years, it was weird at first to see this. But then we realized that function words are used constantly and because of that, their spelling didn’t change like that of other words that were used less frequently! An analogy might be, “If you never get off the train, you never get the opportunity to grab a different jacket!”

I encourage you to read the article that inspired this blog post. There were other senses of ‘the’ discussed, and they were rather well explained. It certainly broadens one’s thinking about a word we’ve all known since we were perhaps three years old, and yet haven’t paid much attention to! Once the reading and spelling of the word was established, attention moved on to other words. Perhaps it’s time to take a second look at some of our function words and recognize their place in our lexicon, in our sentences, and what happens to them in normal speech. It’s certainly an important aspect of spelling that was missing from my own education (and perhaps yours too?) and also from any teaching manual out there. Let’s make sure our students have the advantage of this understanding!

If you are interested in hearing more about stress and how it affects function words in speech, I recommend videos by Rachel’s English. Here is one that I have found extremely helpful. This whole idea provides further proof that our language is a stress-timed language and NOT a syllable-timed language. What that means exactly is another understanding that isn’t found in teaching manuals. We spend so-o-o much time teaching children about syllables when our language isn’t syllable-timed. We spend almost no time teaching children about stress even though our language is stress-timed. We need to stop relying on those programs and those manuals, and start learning about our language for ourselves!