Not long ago in a Science of Reading Facebook group, someone posted a short video created by Reading Horizons in 2016 in which the idea of a ‘scribal o’ was featured. The video explained that when scribes encountered words in which a <u> was adjacent to <m>’s, <n>’s, <w>’s, <u>’s, <r>’s, or <v>’s, they changed that <u> to an <o> to make the word easier to read. You see, the script that scribes used had a lot of broad downstrokes, so sometimes it was difficult to distinguish one letter from the next when similarly formed letters were next to one another.

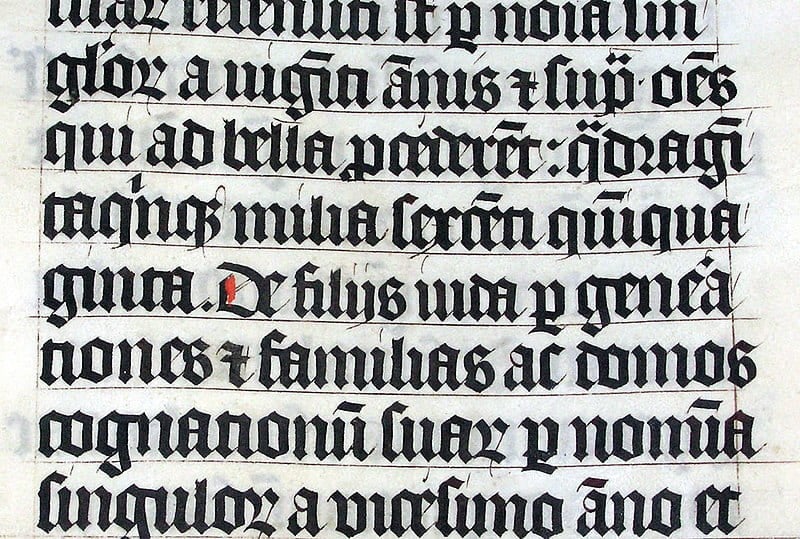

To clarify why the scribes might have thought to make this change, I am sharing a sample of the script known as Blackletter hand. It was used between the 12th and 17th centuries. It may take you a minute to get used to it and to recognize specific letters. Letters I had an easier time spotting were <g>, <a>, <e>, and <f>. With other letters it depended on what letter was adjacent to it. With some words it felt like my eyes were playing tricks on me. Was I looking at an <mi> letter string or an <nu> letter string?

Let me illustrate with the following letter strings. In the first, it could be an ‘n-u-i-n’ or it could be an ‘m-u-n.’ In the second letter string, the <o> in the middle helps make the identity of the adjacent letters more obvious, doesn’t it?

So that is the gist of what is meant by ‘scribal o.’ The pronunciation of the vowel didn’t change, but in certain circumstances the spelling did — the <u> was changed to an <o>. Because of videos like the one I mentioned, the idea of a ‘scribal o’ is becoming more commonly accepted and understood. Classroom teachers, interventionists, tutors and others who work with children have been looking for a way to explain the spelling of words like love, some, done, mother, and Monday, to name just a few.

For teachers who start with pronunciation and then try to explain the spelling based on that pronunciation, words like these stick out like sore thumbs. We would expect the stressed vowel in these words to be a <u> because of how they are pronounced. But in these words that pronunciation is spelled with an <o>. Naturally, teachers want to know why. This idea of a ‘scribal o’ seems to be the answer people have been seeking. In the video by Reading Horizons, the ‘scribal o’ explained the <o> in month, brother, love, come, done, and wonderful.

However, when I saw that list of words, I began to wonder if the idea of a ‘scribal o’ isn’t one of those things that is being broadly and mistakenly applied to any word in which the grapheme <o> represents the /ʌ/ phoneme (the stressed short u).

I responded with the following to both the post in the Science of Reading Facebook group and also with an email to Reading Horizons.

“I can’t seem to find any evidence that ‘Monday’ was ever spelled as *Munday. According to the Oxford English Dictionary and also Etymonline, it is an Old English word spelled then as mōnandæg, literally meaning “day of the moon.” The first part of the word is from monan, meaning “moon” and the second part, dæg, meaning “day.” The word ‘month’ is also connected to the moon as it was thought that a month was the length of time between one full moon and the next. It was never spelled as *munth.

I agree that the ‘scribal o’ explains the spelling in words like ‘love’ which was spelled lufu in Old English, ‘come’ which was spelled cuman in Old English, and ‘some’ which was spelled sum in Old English, but we should be careful about applying that explanation broadly without checking resources.

As I’m looking further, ‘brother’ was spelled broþor (the letter in the middle is like our modern <th> digraph). There was never a ‘u’ in the spelling. And there was never a ‘u’ in the spelling of ‘done’ either. It was always (and should continue to be ) explained as built on the base <do>. The <-ne> is not a productive suffix in English anymore, but we see it on ‘done’ and ‘gone.’ It is negativizing. If something is done, someone is no longer doing it.

Looks like this video, which appears to be a great resource, is misinforming anyone who uses it. Of the six words highlighted in the video, only three have a scribal o.”

I was quite impressed with my response from Reading Horizons. The curriculum developer thanked me for contacting them and apologized for this information not having been researched appropriately. Per my suggestion they are redoing the video and including words that have been verified as having the ‘scribal o.’ In the meantime, they are doing the responsible thing and have removed their video so as not to spread misinformation. I have such respect for a group that responds in this way! I look forward to sharing their new version of this video when it is published!

I’m not sure where the term ‘scribal o’ originated. but I think it is fair to say that most people understand what you mean if you use it. I haven’t been able to find reference to the ‘scribal o’ in any of my resource books which include Richard Venezky’s book, The American Way of Spelling, and several of David Crystal’s books. I have found reference to it at Reading Horizons in a post from 2013, but I don’t get the impression that the term originated with them. I’ve also run across it by watching two videos of teachers instructing their students in regards to this <o>. One of the videos specifically mentions that teaching about ‘scribal o’ was part of Saxon Phonics. In the second video the teacher seemed to be reading from the exact same script, so I’m assuming that the program she was using was part of Saxon Phonics as well.

When I listened to what the teachers were telling their students, I became concerned. The teachers were saying that the words ‘son,’ ‘month,’ and ‘wonder’ were originally spelled with <u>’s. That <u> was changed to an <o> because of mistakes by the scribes who had to copy words by hand. The ink the scribes used ran, making the <u>’s look like <o>’s. Then the teacher went on to say that when an <o> makes the short u sound, it is a schwa. Next the students were to code the words making sure the <o> was coded as a schwa.

My first concern is that this story being told to the children seems unlikely. I can picture this situation of running ink happening in one instance, but over and over? And only with these particular <u>’s? Were there other letters affected by this running ink? I’d love to know the source of this account, wouldn’t you?

My second concern is that the word ‘month’ was never spelled with a <u>! It began in Old English as monað. The Old English letter final in that spelling is eth and is equivalent to the modern digraph <th>. The Old English word is related to the moon. According to Etymonline, the month originally marked the time between one new moon and the next.

My third concern is that the teacher was telling the students that the <o> in son, month, and wonder was a schwa. By definition a schwa is an unstressed vowel. This teacher is telling the students that the only vowel in the word ‘son’ and ‘month’ is a schwa, which conflicts with the fact that we pronounce these words with one principal stress. It is not possible to pronounce these monosyllabic words with unstressed vowels! The third word, ‘wonder,’ has stress on the first syllabic beat and none on the second, yet the teacher is telling the students to mark the first vowel as an unstressed schwa. When the teacher announces the word, the stress is clearly on that first syllabic beat. The teacher does not say, “won-DER,” but rather “WON-der.”

I don’t blame the teachers in this situation as much as I blame the program they are using. The teachers are trusting the makers of the program to have done their due diligence and to be supplying them with accurate information. In this case, they have let the teachers down. Man, have they let the teachers down! It makes you question the other information presented in this program. Unfortunately, the teacher obviously doesn’t understand enough about stress or the schwa to even question this.

But wait. It gets worse. As I was looking through other sites to see what they had to say about this ‘scribal o,’ I came upon another video. This one is called, “Nessy Spelling Strategy -Why is ‘money’ spelled with ‘o’ instead of ‘u’? – Learn to Spell.” There is no mention of the ‘scribal o’ here, but there are questionable rules for teaching students why <o> represents /ʌ/ when followed by certain letters. The letters that supposedly cause this change are called “professors” in the video and they make the <o> go through what appears to be an unpleasant physical change that results in it representing /ʌ/ (as in oven instead of its usual /oʊ/ (as in go).

The first of these “professors” is <v>. According to the video, whenever “professor v” stands behind an <o>, it forces the pronunciation change. To show the effect of “professor v,” the letter <o> goes from having tired looking eyes to having scared looking eyes to looking like a hairy Frankenstein <o>. This rule may work for words like love, oven, above, and dove, but the video forgets to mention that it doesn’t work for stove, clover, move, or prove. The second “professor” is <n>. This rule explains the pronunciation of the <o> in words like month, son, done, and none, but again the video forgets to mention that this doesn’t work in bone, gone, pony, and donut. The third “professor” is <th>. This rule explains the pronunciation of the <o> in words like mother, brother, other, and another, but you guessed it, the video forgets to mention that it doesn’t work for moth, cloth, clothes, and both.

Why teach something as if it is a rule you can count on when, in fact, you can’t? It was not difficult to find words for which these made-up rules didn’t work. What nonsense! What will children think when they encounter words like bone, move, and both? My guess is that they won’t blame this silly video, but rather they will blame a spelling system that seems to make no sense.

If you are wondering how to explain some of this without using silly, half-true gimmicks, let me direct you to the Real Spelling Toolbox. There you will find an excellent description of why we use the letter combination <ov> instead of <uv> when the vowel is representing the /ʌ/ phoneme (the stressed “short u”). In fact, before you decide whether or not to subscribe to the Toolbox, you can read this explanation for yourself (and realize how much else you could learn by subscribing and reading more!) On the homepage there is a link to the sample theme “Learning from Love.” The term ‘scribal o’ is not used, but you will recognize the mention of the scribes, the Black Adder script used at the time, and the confusion caused when certain letters or other similarly formed letters were adjacent to each other.

Another great resource for understanding this switch from <u> to <o> is this video put out by the Endless Knot. Not only do you get an explanation that is similar to that in the Real Spelling Toolbox, you also get some information about the letters <u>, <v>, <w>, and <f>! Ever wonder why the <f> in ‘of’ is pronounced as /v/? Watch this video for an accurate understanding. I guarantee you that no letters will be poked, choked, scared, or harmed in the process!

Is there a “one size fits all’ rule that pertains to an <o> that corresponds to an /ʌ/ phoneme as it does in ‘some’ and ‘Monday?’ No. How unfortunate that we even think there should be. We are so used to quick and easy go-to rules that we have forgotten to use our own sense of logic to interrogate those rules. How easy is it to falsify the rules put out by the professors <v>, <n>, and <th>? Or the explanation that scribes routinely had runny ink every time they wrote a <u> in certain situations? If you want to make this idea of a ‘scribal o’ memorable, ask your students to be investigators. Ask them to find words that falsify what the three professors want them to believe. Ask them whether or not the “runny ink” story seems likely. Then ask them to make a list of words in which the <o> corresponds to an /ʌ/ phoneme. I’ll get you started below. then have them use Etymonline to see whether they were first spelled with an <o> or a <u>. Make two lists and keep adding to those lists as you and your students encounter other words with this <o> to /ʌ/ correspondence.

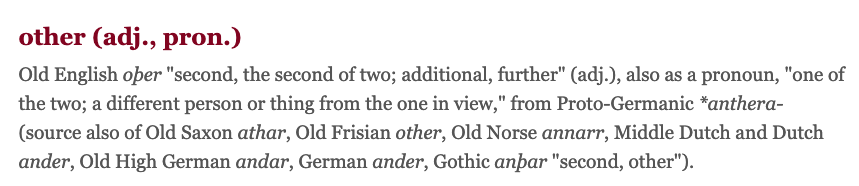

If you hesitate involving your students in using Etymonline for this, let me show you what you are looking for. Here is an Etymonline entry for the word ‘other.’

The information you need is the third word in! It is how this word was spelled in Old English. Notice that it has always been spelled with an <o>. That means that the scribes didn’t need to change it! This isn’t an example of a ‘scribal o’! In case your students are curious about the second letter in the Old English spelling (þ), that is the letter thorn. It represented the <th> digraph we have in Modern English!

So here are words in which the <o> corresponds to /ʌ/. Some of these were originally spelled with a <u>. Some have always been spelled with an <o>. But which are which? Have your students find out!

money brother

Monday nothing

month son

some glove

come shove

done none

wonderful won

love other

Mary Beth, Thank you for taking the time to explain this misconception in such detail! I applaud your tenacity in reaching out to those that were inaccurate. I’m adding this blog post to my list of resources, as I know this scribal “o” conversation isn’t over yet. I am just sorry I only now fell upon this post!

“It is not possible to pronounce these monosyllabic words with unstressed vowels! ”

Quibble, words themselves can be unstressed. ‘I went to the store’ would generally be pronounced with a schwa for ‘to’ and ‘the’

It is true that words themselves can be unstressed when pronounced as part of a sentence. It is also true that it is far more likely that those unstressed words will be function words like ‘to’ and ‘the’ than content or lexical words like ‘son’ and ‘month.’

I, too, had learned this from the Reading Horizons video and have been teaching it as a one size fits all rule for the ‘o’. I am changing my teaching slides pronto. Thank you so much for this wOnderful information!!

Thank you, Laura! As teachers we are always looking to teach accurate information, aren’t we? If I hadn’t previously studied some Old English with my students, I might not have recognized that words like month and brother were mistakenly being identified as having the ‘scribal o!’

I love your posts! Just discovered your blog today!! Thanks for being a word detective and sharing your knowledge.

Thank you! I have really enjoyed writing about my experiences with word inquiry in my classroom. If you ever have questions or want to talk about something specific, please feel free to send an email. teachinfifth@gmail.com

I really appreciate the effort that went into this post. Thank you for calling out misinformation and suggesting better alternatives!

i was just getting ready to introduce scribal o to my student this week and decided to look up a word list to use in teaching it. Ran across your post. Now my lesson will look quite different from what it would have been had I not seen your post. THANK YOU

Thank you for this big smile on my face! Your students will appreciate being detectives in this way and getting an honest explanation of this particular aspect of English spelling. Let me know if other topics arise that seem to have weak explanations. I wrote the post because I questioned one person’s explanation. That is how meaningful learning begins – for students and for teachers!

I just love this post Mary Beth!

You saw misinformation being presented to a massive audience of educators and you presented them with evidence of their mistake. Reading Horizons is to be commended greatly for their response of taking the video down to make sure it is accurate. But a big part of that response is the way you contacted them — with respect and evidence. They still could have ignored you, but boy is it easier to see mistakes in your own work when they are pointed out without respectfully without personal judgement, just clear evidence.

And now that story results in this gift of even more detail about this aspect of English orthography. I’ve learned so much because you took this thread and kept pulling! Many thanks Mary Beth!

I really enjoyed your informative post!!!! Thank you!

Excellent post! Thank you!

Great post and information Mary Beth! I like that you followed up with the sources in such a respectful way. Kudos to Reading Horizons for taking down the misinformed video and re-recording a new one. Your tenacity is making waves. Thank you!

From Gail Venable:

Very interesting post, Mary Beth – great research. And kudos to Reading Horizons for responding the way they did.