The above quote shares the sentiment given in a 1959 lecture by Dr Albert Szent-Györgyi. I have hung it in the hallway in anticipation of our Science Fair every year. But after a few years of replacing spelling instruction with Structured Word Inquiry, I began to realize how well it applied to what we were doing with words. I love that scientists aren’t expected to have answers ready at every turn. Science is methodical and takes the time it takes. Even when research is finished and conclusions are drawn, it is understood that those findings are temporary. They are the current understanding and are open to further questioning and research at any time. And when someone takes the time to research, test, and publish new findings, those findings are thoughtfully considered by fellow scientists who either accept or challenge them. In that respect, science is not static. It is always moving towards a deeper understanding. If you are using Structured Word Inquiry, you will recognize the parallels here.

When I think about the first part of the quote, “If we knew what we were doing,” I recognize that SWI can feel like that sometimes, especially at first. You want to just jump in and use it with students, but so many things nag at you. “What if they ask me a question and I don’t know the answer? What should I do first? What needs to be taught before I begin with SWI?” Personally, I ignored those kinds of questions when I started and asked instead, “How long before my students are asking the kinds of questions that Dan Allen’s students ask?”

(It was on the weekend before we returned from winter break in 2012 that I happened upon Dan Allen’s blog and found out about Structured Word Inquiry. What drew my attention were the questions the students were asking about words and spelling, AND the fascinating discussions that followed. I couldn’t wait to bring it to my students and see what we could learn! How could SWI deepen our understanding of words and help with the spelling struggles that are typically seen in a classroom? It was two days after reading and talking with Dan and Real Spelling that I began talking about words with my 5th graders. Our human resources were Dan Allen, Real Spelling, and Pete Bowers from WordWorks. What a team!)

One of the first words we investigated as a class was ‘prejudice.’ We first encountered it while reading a biography of Martin Luther King, Jr.. It stood out as an interesting word, along with discrimination, segregation, emancipation, equality, separate, justice, integration, civil, and protest. Prior to January of 2013, we would have briefly talked about these words as they were used in the reading, and perhaps the students would have matched up the word to its definition on a worksheet. No doubt a few of my students would have probably requested that these words be added to their weekly spelling test as “challenge words.” But now I was looking forward to something different, something worthy, something that would change our understanding of English spelling. After we investigated this word together, I split the students into small groups so they could each investigate one of the other words and share their findings. So what did we learn with that very first investigation? And how did that investigation shape all the ones I’ve guided students through since then?

Investigating ‘prejudice’

Let’s start with a screen shot from one of my earliest blog posts. It was published on January 23, 2013.

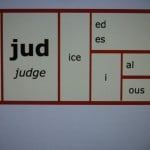

You will notice that all five hypotheses identify <pre> as a morpheme. More specifically, the students identified it as a prefix that they were familiar with. The first hypothesis feels like syllabic division, doesn’t it? The last hypothesis illustrates a knowledge of letters being “dropped” in spellings, but not a knowledge of when or why. This was a great first step.

It is necessary at this point, to remind you that when I began bringing SWI into my classroom, my own understanding of English spelling was on a par with that of my students. These were great hypotheses, but my own preferences over which one might be most likely were based on what “felt right” rather than what I could support with evidence. I was talking the talk, but was in the weeds as far as having a personal knowledge of the regularities of English spelling. But then again everything we do and want to understand begins with that first step, doesn’t it? I was more excited to see what we could all learn through SWI than I was scared to reveal my own lack of knowledge. My excitement overpowered my fear, and that turned out to be a good thing for all of us!

In the second step of our investigation, we read the entry for ‘prejudice’ at Etymonline. We learned that this word was first attested in the 13th century. At that time it meant “despite, contempt.” Earlier in the same century, this word was used in Old French with the same spelling we see today. Prior to it being in Old French, it was in Medieval Latin and spelled prejudicium. Earlier yet it was spelled praejudicium in Latin where it meant “prior judgment.” This earliest spelling could be analyzed as prae “before” and judicium “judge.” We talked about the fact that the sense and meaning of this word hadn’t changed much in all the years that it has existed. We use it today to denote a sense of prejudging a person and usually in a negative way. At that point we felt ready to collect some words that might be related. We were off to use Word Searcher by Neil Ramsden.

It was at this point that we missed an opportunity to have a better understanding of what we would be looking for at Word Searcher! We had boatloads of enthusiasm, but lacked experience in conducting word investigations. You see there was a hyperlink to the related word ‘judge’ in the entry at Etymonline that we ignored. There was pertinent information related to the spelling of ‘judge’ that would have made us look differently at the words we found. But we were eager and jumped a little too quickly to the next step.

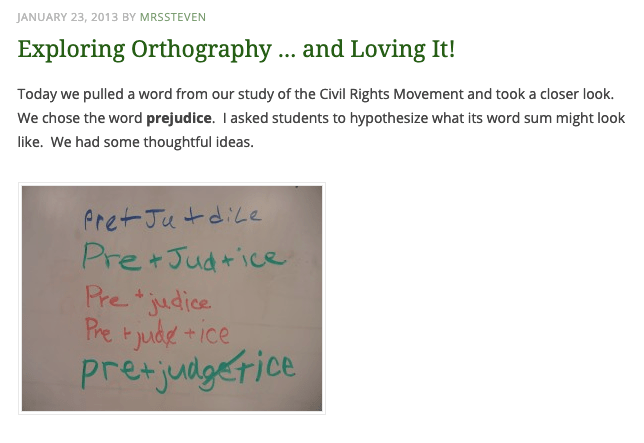

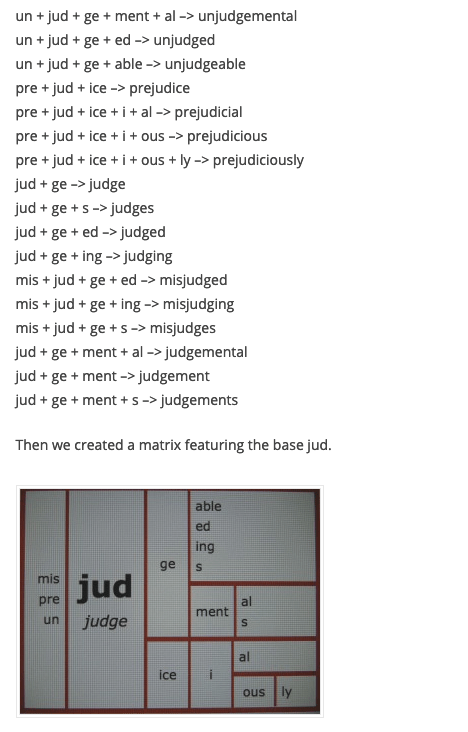

We found a list of words that we knew to be related in meaning to both ‘prejudice’ and ‘judge.’ We thought about the spelling of each word and noticed which letters were exactly the same in each word. We wrote the word sums listed below and created the accompanying matrix. The following is another screen shot from that January, 2013 blog post.

At this point we were pretty pleased with ourselves. We had noticed that all of the words had <jud> in common. We made the leap that it was the base. Did I really think that <ge> was a suffix? I thought, “Maybe.” I mean, my head was just as full of “spelling is random” as my students’ heads were. Let me interject that at this point I had been teaching for 18 years, and none of the spelling curriculum I had been handed talked much about suffixes beyond <ing>, <ed>, <s>, and a few others. You added them to words, you removed them, and you learned rules like “Double, Drop, Change.” Our spelling books focused more on the “vowel pattern” (pronunciation) and word use. My college education didn’t include much information either. There was a Language Arts textbook that was focused on teaching children to read, but it didn’t really reveal much about spelling. Anything I knew about words and how they can be considered to be made up of parts, I deduced from my own K-12 schooling and by noticing words when I read. Obviously I was missing some pretty foundational pieces! Everything I was learning as I introduced Structured Word Inquiry to my students was as new to me as it was to them. And I must say we had a glorious time learning together!

What is it that I missed?

Had I followed that hyperlink at Etymonline to the entry for ‘judge’, I would have learned that as a noun, it was first attested in the mid 14th century. At that time it was used to mean “public officer appointed to administer the law.” Earlier it was from Old French juger, and further back in Latin it was spelled as iudex and meant “one who declares the law.” I might have been confused by the spelling in Latin. Why was an <i> the first letter in the Latin spelling? In Spellinars I have taken since (particularly Latin for Orthographers), I learned that in Latin, <i> and <j> were considered to be the same letter. It may sound confusing, but the people who spoke Latin understood its use well. Here is an excerpt from the book Letter Perfect by David Sacks which gives more information on this.

“… the shapes j and i were being used interchangeably to mean either a vowel sound or a consonant sound (which in English was “j”), and similarly, shapes U and V were used interchangeably for a vowel or a consonant, “u” or “v.” In the hands of printers of the 1500s and 1600s, shapes J and V gradually became assigned to the consonant sounds. Later J and V would officially joint the alphabet as our final two additions, letters 25 and 26.”

There are, of course, a number of books available that will provide a more complete understanding of these two letters, along with all the rest. As I reflect on finding out that letters, too, have stories, I am reminded of a particularly lovely moment from a year ago. We were looking at a sentence on the board and focusing on each of the words. We were noticing what language each word was from. A student raised her hand and asked a question that no student has ever thought to ask before. “If words have histories, and letters have histories, where do punctuation marks come from? Do they have histories too?” I still smile and can picture the student asking it. I think it stays with me because it reveals how curious this student had become about our language. I like to picture this student slowly opening a door and seeing more of what’s on the other side, bit by bit. The eyes widen in wonder. Back to Etymonline’s entry for ‘judge.’

A less hurried scholar wouldn’t have stopped with the entry for ‘judge’ either. I should have kept reading. The next entry as you scroll down is for <judge> as a verb. Its attestation date as a verb is 200 years earlier than as a noun! At that time it was spelled iugen and was used to mean “examine, appraise, make a diagnosis.” Moving forward to c 1300, it was used to mean “to form an opinion about; to inflict penalty upon, punish; try (someone) and pronounce sentence.” Now moving back in time prior to its attestation date, this word is from Anglo-French juger, Old French jugier. Further back it was from Latin iudicare meaning “to judge, to examine officially; form an opinion upon; pronounce judgment.” From there we learn it is from iudicem (nominative iudex) “a judge.” What comes next in the entry is very interesting. The Latin iudicem was a compound of ius “right, law” (see just (adj.)) + root of dicere “to say.” You can see that in the spelling of iudicem, right?

And then in the next paragraph there is this, “Spelling with -dg- emerged mid-15c.” If I look back at the spellings of this word as it moved from one language to the next, I see that in Latin the first three letters were <iud>. In Anglo-French and Old French, the first three letters were <jug>. Then in mid-15c. the spelling with <dg> emerged. Hmmm. A good place to get evidence to illustrate this is the Oxford English Dictionary. There are citings of the word being used over time. Below I have listed the year and how one of the ways it was spelled at that time. What is interesting is the inconsistency in spelling prior to 1500. Then from 1500 to 1600 we see a consistent spelling, but with <i> instead of <j>. As we learned earlier, it was with the use of the printing press that the <i> (when representing a consonant) came to be represented with a <j>. It is also when <j> became an official letter of our alphabet.

?c1225 iuge

c1400 jugged

c1475 iugid

1486 Iuge

1534 iudge

1547 iudge

1597 iudge

1645 judged

1680 judged

1711 judge

What this information tells me is that the <ge> can’t possibly be a suffix in the words judge, judgment, judgmental, misjudge, or in many of the other words that were included in my first matrix. What this information makes clear to me is that ‘prejudice’ and ‘judge’ do not share a base in modern English! The <ge> cannot be a separate morpheme from the <jud> in the word ‘judge.’ How do I know that? Because if I think about the graphemes in this word, I will note that there are three (j.u.dg) with the single final non-syllabic <e> functioning as a marker (marking the pronunciation of the <g>). If the <d> is part of the digraph <dg>, it cannot cross the boundaries of the morphemes to do that. Remember that a morpheme is made up of graphemes that represent phonemes. And letters in two different morphemes can never combine to become one grapheme.

That understanding is something I didn’t have when I made that first matrix. And that’s okay. I believe that a matrix is more like a snapshot of one person’s understanding at a given moment in time than it is like an answer key for anyone else. It is so tempting to see a matrix that someone else made and grab it to use in your own classroom. In fact earlier this summer I saw a teacher happily sharing a whole set of word matrices that she made in preparation for this fall. Is that a bad thing? Not necessarily. But is there a good chance that many teachers will happily use those without looking carefully at them ahead of time? I think there is. If there is something on the matrix that they question, my hunch is that they will distrust their own thoughts and assume that someone else’s work must be right. It is so important to carefully look at a matrix and to question things that maybe you wouldn’t have put on there yourself. My first matrix is a good example of that. If other teachers use it without questioning that <ge> suffix I listed, they will spread their own misunderstanding. They won’t be spreading mine because I have moved on from what I understood then. From that one matrix, I made two that reflected our new understanding. This is a common and acceptable part of learning, isn’t it?

I’m so glad that this experience was one of my first. I’m glad I blogged about it then, and now I’m glad to be able to reassure others new to SWI that they can expect to learn along the way. Here are two valuable things I have kept in mind as I have continued to jump into word investigations with students in the years since.

1

Let go of the need to be right all the time in front of students. I used this opportunity to celebrate having learned something that probably felt quite obvious to others. It’s not my fault that I didn’t learn about graphemes, phonemes, and morphemes until that point in time. The students can relate to that feeling. How often have you seen that look on a student’s face – the one where you know they are feeling bad because they didn’t know something everyone else seemed to know. I make it a habit to share how delighted, even giddy I feel when I’ve learned something that I didn’t even know I didn’t know! Enthusiasm is catchy! And modeling this kind of response to having a misunderstanding gives students a healthy alternative to feeling bad. There should be joy at having learned something. And when a misunderstanding becomes an understanding, learning has occurred!

There is another side to this need to be right and to be ready. Often we feel obligated to anticipate the questions that the students are likely to ask and to be ready with an answer. If an unanticipated question is asked, we still feel the need to answer it as best we can. What if we didn’t feel the need to answer every question? Some of my absolute best classroom moments have happened when I put the question back on the student and listened to them think through their own question. Or let others respond which gave the original questioner a different perspective – one that they didn’t have to assume was correct (like they might if it came from the teacher). It is also a powerful thing to say in front of your students, “That is a brilliant question. I have no idea what the answer is. But I can tell you this. I will be thinking about your brilliant question all day!”

2

Don’t rush through the etymological story in order to get to the matrix. The teacher I mentioned previously that shared a whole set of matrices with other teachers did so thinking she was doing them a favor. They even thought that she was doing them a favor. But what none of them realize is that researching and gathering a list of related words in preparation for a matrix is a marvelous opportunity to walk through a word sum hypothesis yourself. Certainly there are words that may stump you (is that a prefix or a base?), but by figuring out where to look or perhaps who to ask, you get better at the process. And when you feel better at the process, you can exude a calm when faced with uncertainties in your classroom. Because of your experience, you will offer suggestions of where to look for the evidence to support the current thinking in regards to a specific word. Exactly what do those teachers using someone else’s matrix know about the story of the base on each of those matrices? What interesting tidbit can they share with their students (or find with their students) about that base’s history? Can any of the graphemes in the base’s spelling be explained by information found in the word’s ancestry? How old is the base and what language did it originate in? Of all the words that can be completed using the elements on the matrix, which is the oldest? The newest?

There are many reasons for using a matrix with students. A person definitely doesn’t need to know everything I’ve mentioned above in every instance. But there ARE interesting things to know, and quite often it is those interesting parts of the word’s story that are memorable to the students. And we want the students to remember the words, right? A matrix can be part of an activity, but if you present filled out matrices to your students week after week, what are your students learning about determining a word’s structure for themselves? Think of it this way. Is using someone else’s summary of a book a great way for you to completely understand the book yourself? Of course not. You would be missing many of the finer points. Make sure your use of matrices is part of a larger picture of a word. It should include the sense and meaning of the word, its etymology (which can reveal so many things), and a look at its grapheme/phoneme correspondences. The matrix celebrates a family of words. The other questions of SWI reveal the details of that family.

I guess my big message here is to mix up the way you use matrices. Sometimes you create them, and sometimes your students create them. Sometimes they are part of a full investigation, and sometimes they are used alone because there is something specific you want to highlight. ALWAYS carefully consider a matrix that someone else has made. If it jives with your understanding, great. If it doesn’t, don’t assume that questioning it is off limits. It doesn’t matter who created it! Be discriminating and teach your students to do the same. This is part of achieving a more solid understanding no matter what you are examining.

I have met many wonderful people while teaching my “Bringing Structured Word Inquiry into the Classroom” online class. At the first thought of using SWI, there is hesitancy. There is a feeling that there is so much to learn before they could ever start using SWI with children. It is true that there is much to learn. But there are resources, classes, workshops, and people to help. And there are the wise words of Aristotle.

“For the things we have to learn before we can do them, we learn by doing them.”

Definitely take some classes and ask some questions. By all means purchase a subscription to Real Spelling’s Tool Box 2! And then begin doing, so you can learn.

Not to dismiss the underpinning sentiment of your leading quote “If we knew what it is we were doing, it would not be called research. Would it?”, I thought I’d better let you know that it is not by Einstein. And, that it’s not a true quote at all. It’s a one of those ‘internet whispers’ that have been around long enough, and repeated and reworded often enough, that everyone takes it as a ‘truth’.

The reality is that it came from a different Albert, and that it was recounted by Aldous Huxley in his collection of lectures entitled ‘The Human Situation’ in 1978. The real statement, by Dr Albert Szent-Györgyi, made presumable around the time of the lectures in 1959, is as follows:

“When I first came to this country ten years ago, I had the

greatest difficulty to find means for my basic research. People

asked me, what are you doing, what is it good for? I had to say, it

is no good at all.

Then they asked, then exactly what are you going

to do? I had to answer, I don’t know, that is why it is research.

So the next question was, how do you expect us to waste money on

you when you don’t know what you do or why you do it? This

question I could not answer.”

(Huxley 1978, pp. 104-105)

As I said, this does not undermine the sentiment in which you used it, in fact it probably strengthens it given that Huxley used it in his discussion on the value of basic research over the ad hoc or targeted. But it would be nice to promote the original author, a Nobel Prize winning researcher himself, over the noise of internet fiction.

Kind regards

Glenn P. Costin

This is a fantastic post Mary Beth. I will be sure to share it with others. It’s a journey for sure!

Thank you, Fiona. I know that some people will launch this ship smoothly and others will rock among the waves for a bit. But no matter how the journey begins, I hope each person embraces where they are, and minimizes any guilt about not knowing certain things right off the bat. A celebratory attitude about learning is good for the teacher, and it is good for the students!

This is spectacular, Mary Beth. A profound message. And not only for those contemplating their first steps in this journey.

Thank you, Gail. There are many things I have learned since I began studying orthography. Much of it is related to English spelling, but a great deal of it is related to not cheating ourselves or our students out of opportunities to learn. I know how tempting it is to set things up ahead of meeting with students, or to do part of the “work” in anticipation of them doing the finishing part.

But to me that is as if someone told you what happened in the first part of the movie and let you watch the ending. Much of the impact of that ending is lost because you were not involved or invested in the whole first half. I hope some educators pick up on that message in this post and give some thought to making sure the students are involved as much as possible all the time.