For about two months in late fall, I worked with a group of 12 students for 20 minutes a day, four times a week. These were students I also saw for 90 minutes every day when they came in as part of their homeroom. This small group opportunity is part of what our school calls WIN time (WIN stands for What I Need). As a grade level team, we talk about the needs we see and how to group the students so we can address those needs. I asked for this particular group of 12 based on spelling errors I saw in their writing samples at the beginning of the year. What an opportunity to reinforce some reliable concepts in our language!

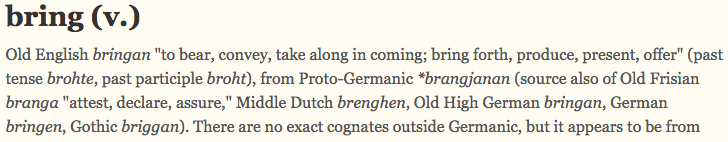

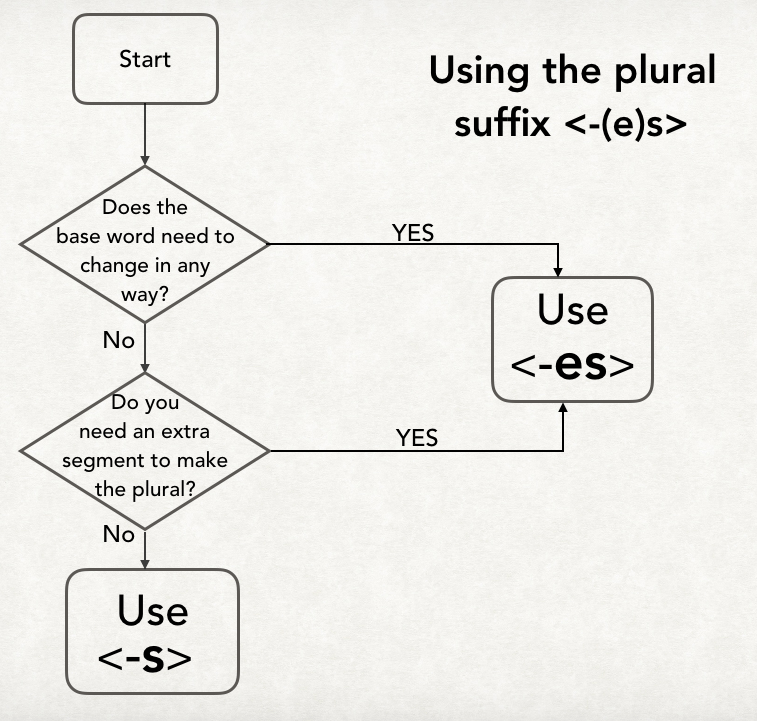

We started by looking at words that take an <-es> suffix versus those that take an <-s> suffix. I picked this because it’s a great place to begin noticing things about suffixing, digraphs, and roles of the single final non-syllabic <e>. I could have started with any number of activities. In fact, it seems that no matter where I begin when talking about English spelling, we end up reinforcing many ideas, just in different contexts. That is the beauty of teaching with a Structured Word Inquiry focus. We think about something particular, we collect some words to examine what it is we are focusing on, we make some observations about what we are seeing, and in the process of all that, we deepen our understanding of many things. Most important of all, we build an understanding of the connectedness of these concepts and facts about how our spelling system works.

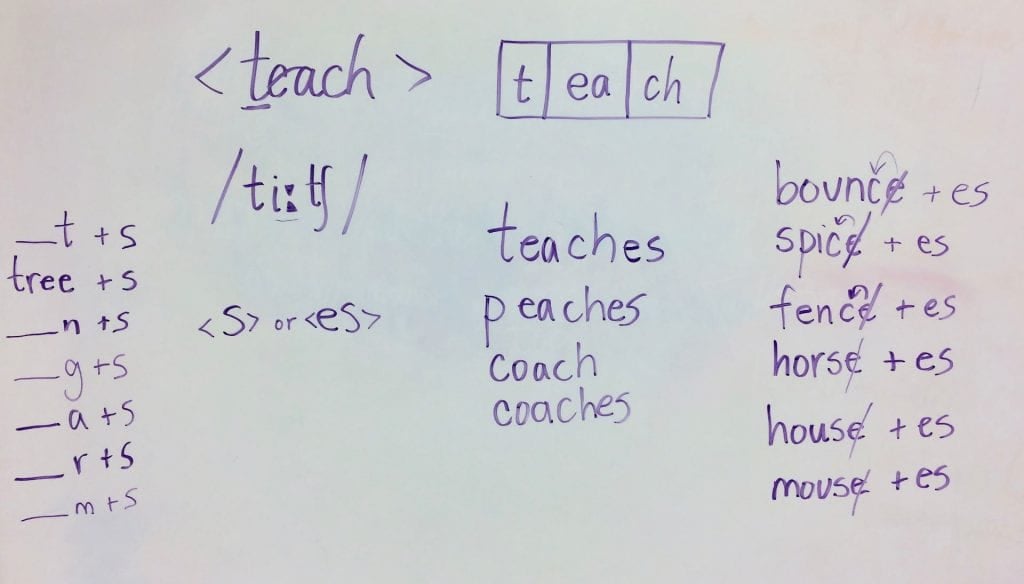

Another reason I chose to start with the <-s> and <-es> suffixes is that I wanted to give this group a preview of them before we discussed them as a larger group. It always amazes me how much we can talk about in only 20 minutes! We began by talking about using angle brackets to represent a spelling. When we see a word in angle brackets, we spell it out. We don’t announce it. When we want to announce it, we can either write the word without angle brackets at all or we can represent the pronunciation in IPA. If we use IPA symbols, we use slash brackets. As you can see below, I demonstrated with the word <teach>. I also showed the students how we might represent the graphemes and digraphs in the word <teach>. The word has 5 letters and 3 graphemes. One of the graphemes is a single letter grapheme, and the others are digraphs. I don’t spend too much time on what I have just described because with this group beginning in mid-October, this information is already something we are reviewing.

The next thing we did was to talk about words that can take an <-s> suffix. If you look at the left side of the picture below, you’ll see that as the students suggested words, I was writing the final letter of the word + s. In this way I could encourage the students to think of words that ended in other ways (besides words that end with the same letter that was previously named). Since we already had the word <teach> on the board, I asked what suffix we would add if we wanted to talk about the person who teaches in the next room. In this case, we are not adding a suffix in order to make the word plural. We are adding a suffix to indicate the verb tense. A few of the students knew we would add an <-es> suffix to <teach>, <peach>, and <coach>, but no one knew why.

When someone asked about <bounce>, I wrote it out as a word sum. When a word ends in a single final non-syllabic <e>, it is not as obvious to the students that the suffix being added is an <-es>. When we compare the spelling prior to adding the suffix to the spelling of the word after the suffix has been added, it would appear that only an <s> was added. But that is not the case.

In order to understand why we need an <-es>, I directed the focus to the word someone had thought of that ended with a final <t> – <pits>. We announced the word <pits> as /pɪts/ and noticed that we could easily feel ourselves adding the /s/ after the /t/. Then we announced the word <teaches> as /titʃɪz/ and noticed that immediately following the /tʃ/ we said /ɪz/. In fact we found it awkward and unsuccessful to follow the /tʃ/ with either /s/ or /z/ by itself. In other words, we needed the suffix to be <-es> which would add an /ɪz/ to the pronunciation of the base.

Now we took a look at <bounce> (the rest of that list wasn’t there yet). We tested to see if we could just add an <-s> suffix to bounce. The students realized quickly that the word ends with an /s/ already. Adding an <-s> suffix wouldn’t work. In announcing the word with the suffix added, we wouldn’t know where one /s/ left off and the next one began! Then they tried adding the /ɪz/ of <-es> to the base /bɑʊns/. That worked!

My next question to the students was, “Why does the word <bounce> have a final <e>?” No one was sure. There were guesses about the vowels in the word, but in this word, the <e> had a different role. I asked if anyone could think of two more words that were similarly spelled. The words <spice> and <fence> were suggested. I asked, “Why weren’t we able to just add an <-s> suffix?”

“Because there was already an /s/ at the end of the word and it would end with /s..s/!”

Of course that led to lots of students trying to demonstrate how it wouldn’t work. But that’s okay. I know they understand.

“Does the <c> always represent /s/ in a word?”

“No. It’s a /k/ in <cat>. Oh! The <e> tells us the <c> is /s/!”

We noted that in <spice>, the <e> was doing two things. It was also indicating that the <i> would be pronounced as /aɪ/. Next I asked if they could think of words that ended with a /s/ pronunciation, but were not spelled with a <c>. They quickly thought of horse, house, and mouse. We discussed the role of the single, final non-syllabic <e> in these words. The <e> in these words had yet a different role! It was preventing the words from looking like plurals when they clearly weren’t! My favorite examples of where leaving off the final <e> would truly confuse a reader are please and pleas and dense and dens. A student may not recognize why someone would think *hous is a plural word since *hou isn’t a word in English, but they will recognize that dens are where some animals live.

I left our notes on the board and explained the work my WIN group had done to my regularly scheduled classes. The 12 were scattered among three classes and were eager to explain things for the rest of their class when the opportunity came up.

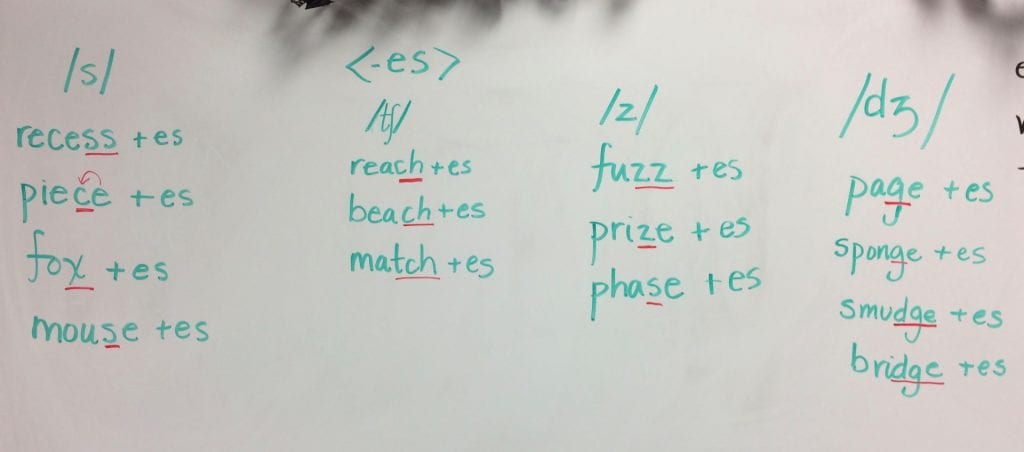

Day 2

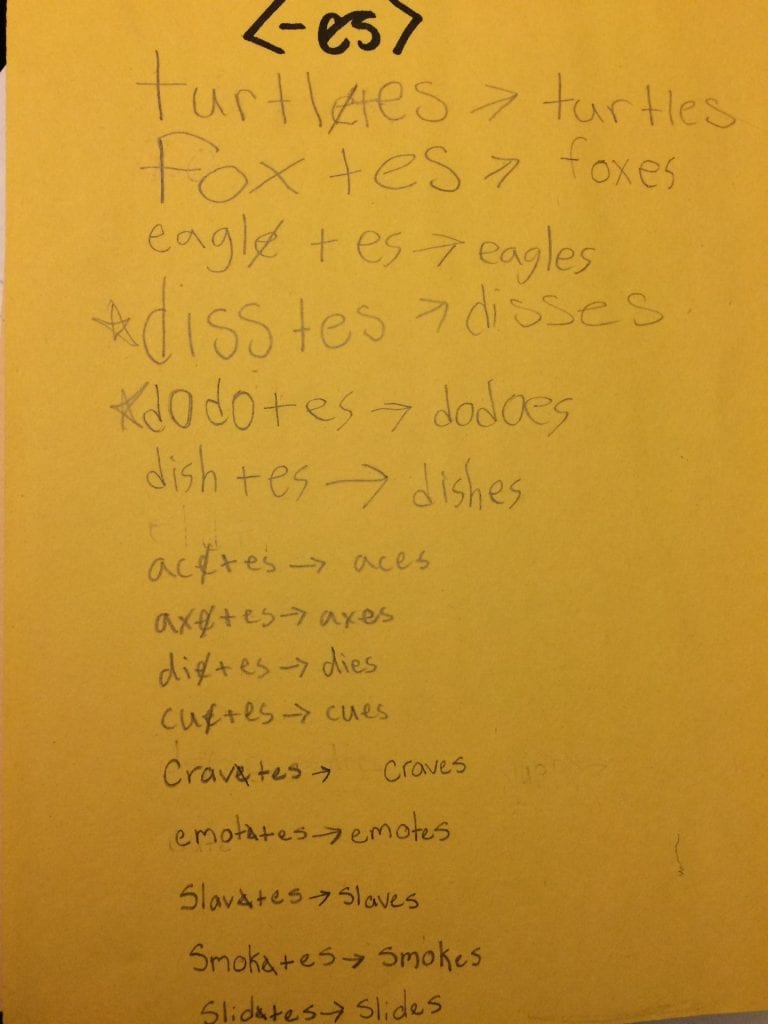

The next day I wanted to continue looking at words that take an <-es> suffix. I wanted to focus on the ending grapheme/phoneme correspondences when the word was in its singular form. I listed the headings and together we noticed which graphemes could represent those phonemes. In the first column, I started by underlining the final <tch> trigraph and/or the <ch> digraph. then we moved to the middle two columns that ended up including four different graphemes that could represent a final /s/! As you can see, I wrote out word sums so they could see over and over that with these word final phonemes, we would need to use an <-es> suffix. I also underlined the final graphemes in each word. As we went along, the students tried adding an <s> pronounced as /s/ and then quickly knew they needed to add an <-es> pronounced as /ɪz/. With words in the last column, we talked about the single, final non-syllabic <e> that was following the <g>. The students wondered aloud if it was like the <e> that follows a <c>! So then we could compare the <g> grapheme (when followed by an <e>) to the trigraph <dge>.

The last thing I did was to point out the vowel in front of the trigraphs <tch> and <dge>. I asked if the students recognized whether they were considered short vowels or long vowels. We said them together and they identified them as short. I underlined them in red.

Again, I left our work on the board and shared our findings with the three larger classes.

Day 3

While sharing with the larger groups yesterday, someone asked about words with a final /z/ phoneme. How brilliant, right? Of course we added another column today and explored the graphemes that could represent the phoneme /z/. Once more we went over the different final graphemes and proved to ourselves that they couldn’t take an <-s> suffix, whether it was representing an /s/ or /z/ phoneme. The words with these final grapheme/phonemes needed to take an <-es> suffix that would be announced as /ɪz/.

Day 4

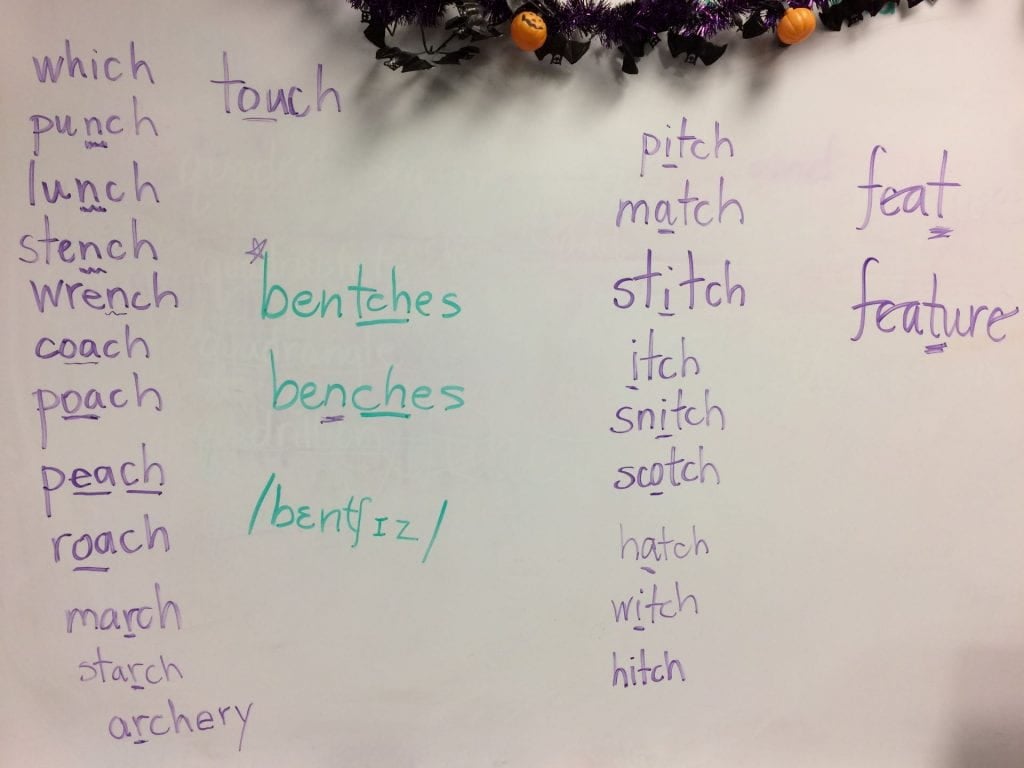

Today we went back to explore the words with either a final <tch> trigraph or a <ch> digraph. The students brainstormed a bunch of example words of each. Then we made observations about what was immediately in front of each. We began to notice some consistencies. In front of a word final <ch> digraph there was either a consonant or a vowel digraph. In front of a <tch> digraph there was a single short vowel. We wondered if this could explain why a <ch> is used in <bench> and not a <tch>. It was time to get the students working on their own. I split them into groups of two. This is my favorite group size for word investigation. Here are the specific topics of inquiry for each group:

~words in which a consonant precedes a final <ch> digraph.

~words in which a vowel digraph precedes a final <ch> digraph.

~words in which a single vowel precedes a final <tch> trigraph.

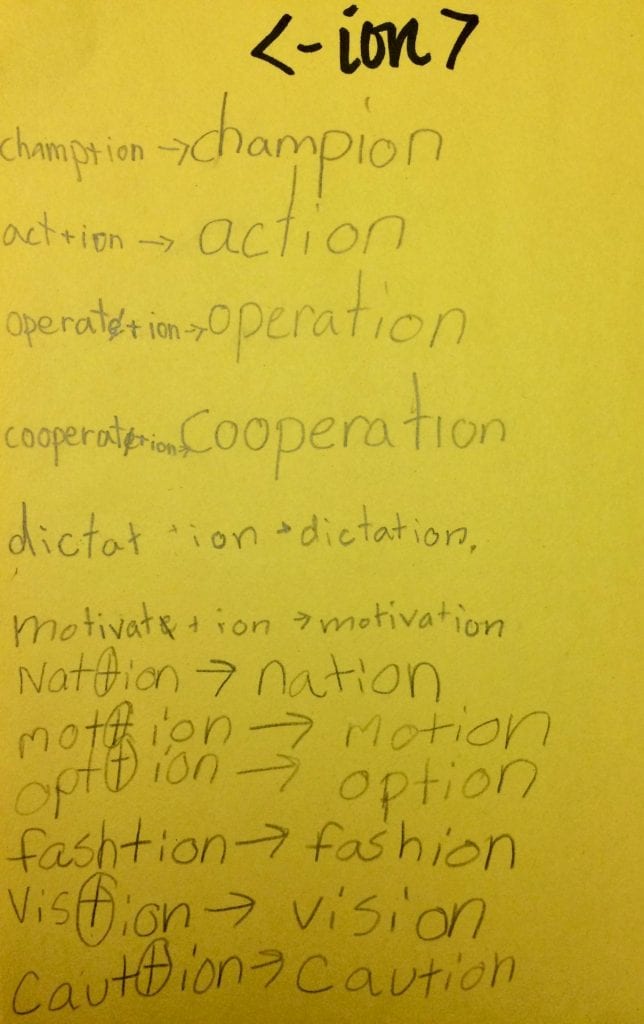

~words with a final <t>, but whose pronunciation changes when an <-ion> suffix is added.

~words with a final <t>, but whose pronunciation changes when a <-ure> suffix is added.

~words that take an <-es> suffix.

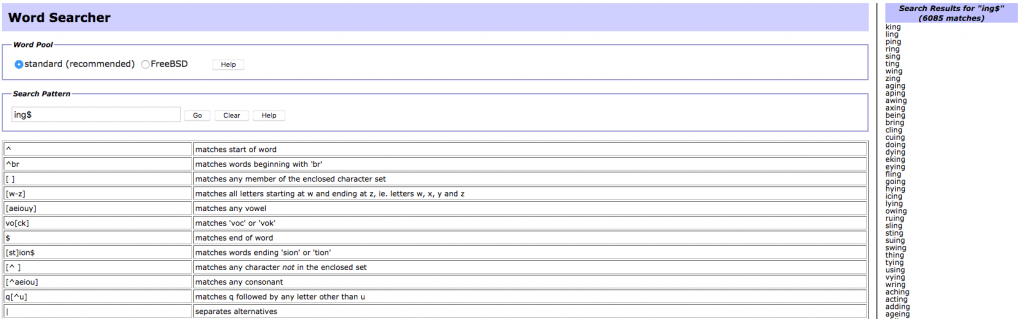

And they were off! They got out their orthography notebooks and turned to the next available page. One in each group grabbed a Chromebook so they could look at Word Searcher to find words with the targeted word ending. They also had a dictionary handy in case there was a word they didn’t know. I walked around to make sure each group was clear on what they were looking for. Then I let them work on their own for the rest of the time.

Day 5

Another group work day. They were collecting words and keeping track of them in their notebooks. I walked around and checked in to make sure they weren’t collecting words they didn’t know when there were plenty of words they did know to choose from. That seems like something I shouldn’t have to do, but my students are new to tasks that ARE NOT busy work. They are used to mindless spelling tasks in which they aren’t expected to really think about what they are doing and why. After years of Words Their Way, they are used to shifting words into piles that don’t necessarily make sense to them. The words are moved there because of some surface-y reason that does not have any basis in the logic of our English spelling system. And the students learn to do the task without asking the kinds of questions that lead to a better understanding that logic.

Day 6

I circulate, guiding the students in now grouping the words they found. If they found a vowel digraph in front of the <ch> digraph for instance, how many words did they find with that same vowel digraph? How many different vowel digraphs did they find? Each group had some organizing to do before they could make observations.

Day 7

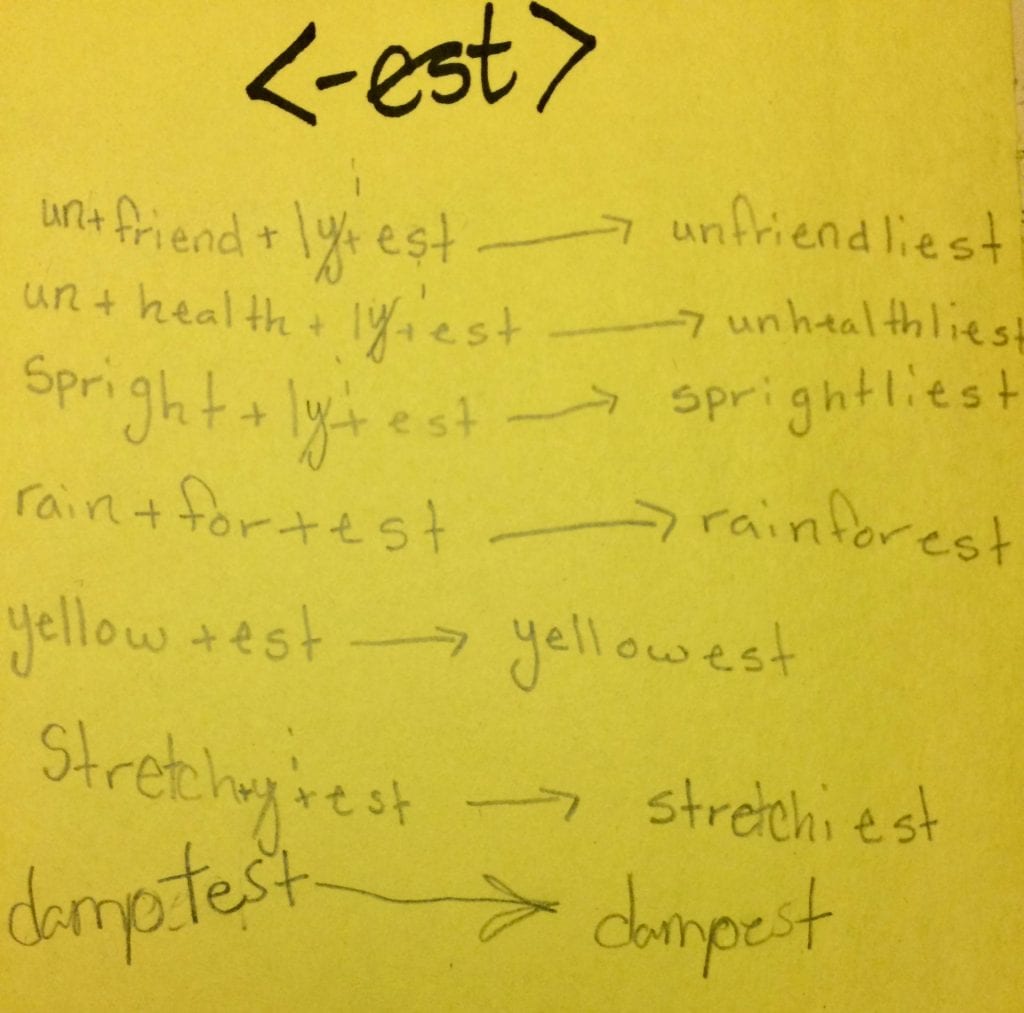

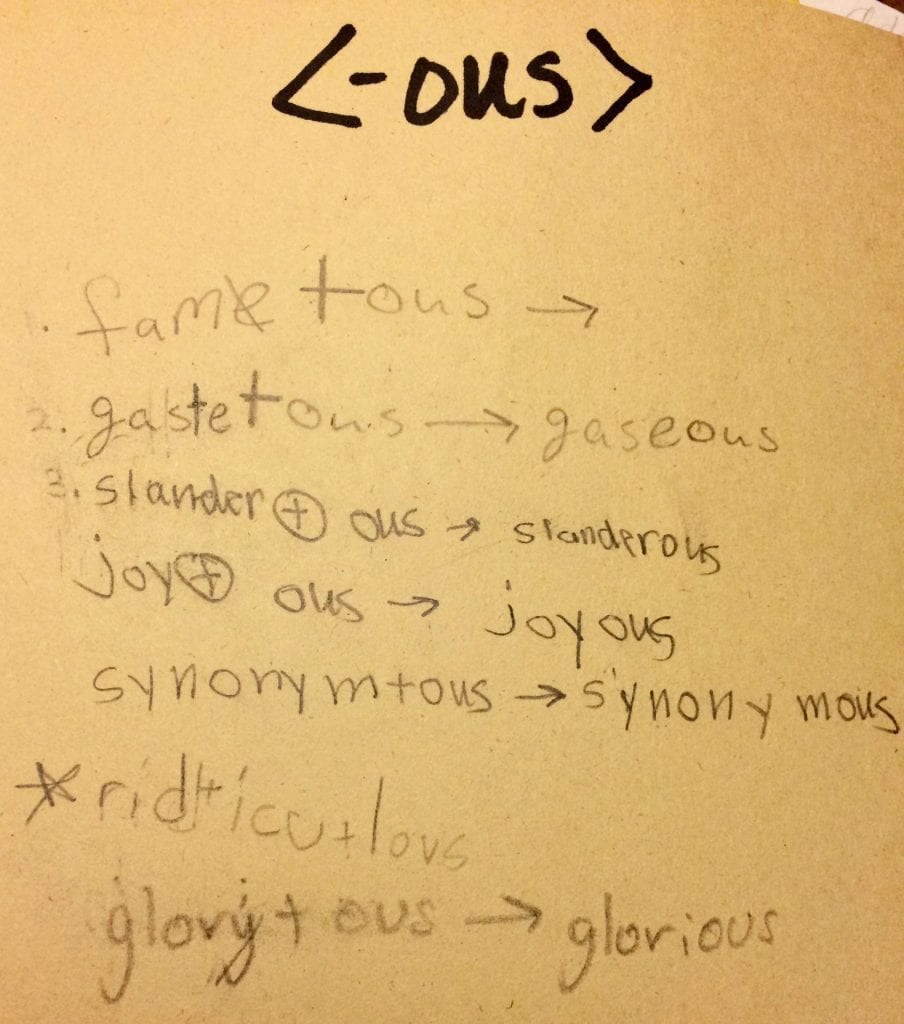

By this point, the groups were not all at the same point in their investigations. That makes sense because they were investigating different things. When one group starts making a poster or chart, the other groups get a little concerned. They ask, “When is this due?” I always tell them that they will be given the time they need, provided they stay focused and productive each day. The groups that were investigating digraphs and trigraphs were given large graph paper so they could share their findings by creating bar graphs. The groups looking at a word final <t> and what happens to its pronunciation when an <-ion> or <-ure> suffix is added, made their own posters. I asked them to include a page where they color coded the graphemes and phonemes in each word so we could see how the grapheme <t> ended up representing more than one phoneme.

As the groups finished, I asked them to write scripts. What would they say as they presented their findings? I told them that when they had a script written, I would revise it, edit it, and then I would record their presentation with my camera. They liked that idea! I liked the idea that they now had to think through their observations as they were writing them down. This took several days, and the video recording took several more for each group. When one group was completely done, I gave them another investigation that could easily be finished with our regular classroom work (back with their homeroom groups).

Here are the videos sharing the investigative work they did.

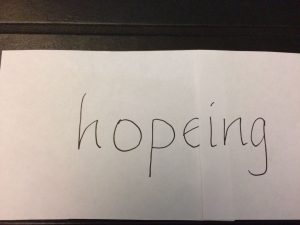

As I was filming these, I saw that a few groups of students chose words that they didn’t know. I was hoping to catch those prior to the presentations, but obviously I didn’t catch them all. When I asked the students if they knew those words, an interesting thing happened. They said they did! And then they proceeded to announce the words. Do you see here what I see? The students who struggle with reading and writing the most believe that announcing a word means you know that word. Can they use it in a sentence? No. Do they know what it means? No. But they have been taught (without the words necessarily having ever been said out loud) that announcing a word is what’s important in reading. It is more important than what the word means. Fluency over comprehension. That is what the students think. This is why I will always push the idea that a word’s meaning is the most important thing to know about a word. Once we know its meaning, we can research to understand its spelling and then its pronunciation.

I have seen the effects of the small group work with the students mentioned in this post. On a day that we were reviewing suffixes, they spoke up confidently about when to use <-es> versus <s>. In the group work we are currently doing, they no longer sit quietly. They contribute. They question. In their daily work I am still seeing spelling errors. Of course I am. I cannot single handedly help 75 students understand every single spelling error they make. But what I can do is help them understand some of the consistent patterns we see in English. Notice I said to “understand some of the consistent patterns.” Up until now they may have been required to memorize lists that had consistent patterns, but that is not the same as understanding why a spelling is one way and not another. What I teach helps them understand the spelling of many words – even words they don’t know yet. I am teaching how the system works, not just how a single word is spelled.

Once the last group was finished with video recording, the WIN groups were reshuffled so that other needs in other areas could be addressed. I have a new group now. We are not working on word investigations. This time we are reading Peter Pan and stopping to talk about the colorful and often times unfamiliar vocabulary used. We also pause to look at the specific writing techniques of James M. Barrie.

And just in case you are wondering, our current project is focused on the topic of assimilated prefixes!