This is what I shared with the parents of my students at our recent set of conferences. Since those conferences were scheduled three weeks before the end of the trimester (which meant that my grades were not yet finalized) I used the opportunity to explain what I teach under the heading of orthography.

I began by explaining that one of my goals is to teach students why words are spelled the way they are. A word’s spelling is primarily representing meaning, and not pronunciation. An example of what I mean by that is the word <goes>.

On the day after our final performances of The Photosynthesis Follies, I gave a photosynthesis test. As I was correcting the tests, I couldn’t help but notice that more students than I would’ve thought, misspelled <goes>. Five students spelled it as *<go’s>, two students spelled it as *<gos>, three students spelled it as *<gows>, three students spelled it as *<gose>, and one student spelled it as *<gous>. Sometimes when I mention to colleagues that students struggle with spelling, their first reaction is to say, “They need more phonics! Those lower grades must have stopped teaching phonics!” But I say no. It is pretty obvious that the students have learned to spell phonetically. Anyone reading their work can guess what word they intended to spell. They are spelling using the only strategy they’ve been taught: Sound it out. And if we started naming words that are similarly difficult to spell accurately using only “sound it out”, we could name quite a few. Don’t you agree? So what now? If the problem isn’t phonics, what is it?

Well, what if, when we were teaching our students that graphemes represent pronunciation, we also taught them that words have structure? What if the students were taught to look at this word and recognize that <go> is at the heart of its meaning? We could teach them that this word starts with its base element, <go>, and if we want to form other words using this same base element, we could add suffixes. If the child is learning the spelling of <goes>, he/she is probably familiar with the words <going> and <gone> as well. We could teach the student that <go + es is rewritten as goes>, that <go + ing is rewritten as going> , and that <go + ne is rewritten as gone>.

If we look at other word families in this same way, it won’t take long before the student has learned some of the more commonly used suffixes and prefixes. So even with early readers, recognizing some part of a word will help when encountering unfamiliar words. When decoding, the student can focus on the base element in the word because they recognize a suffix they can remove.

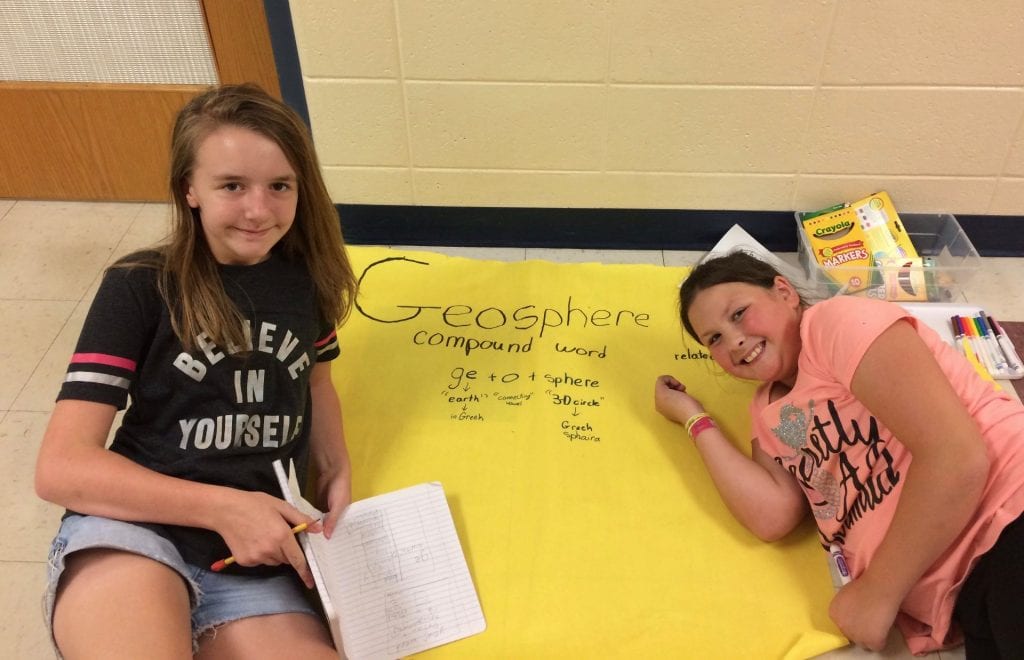

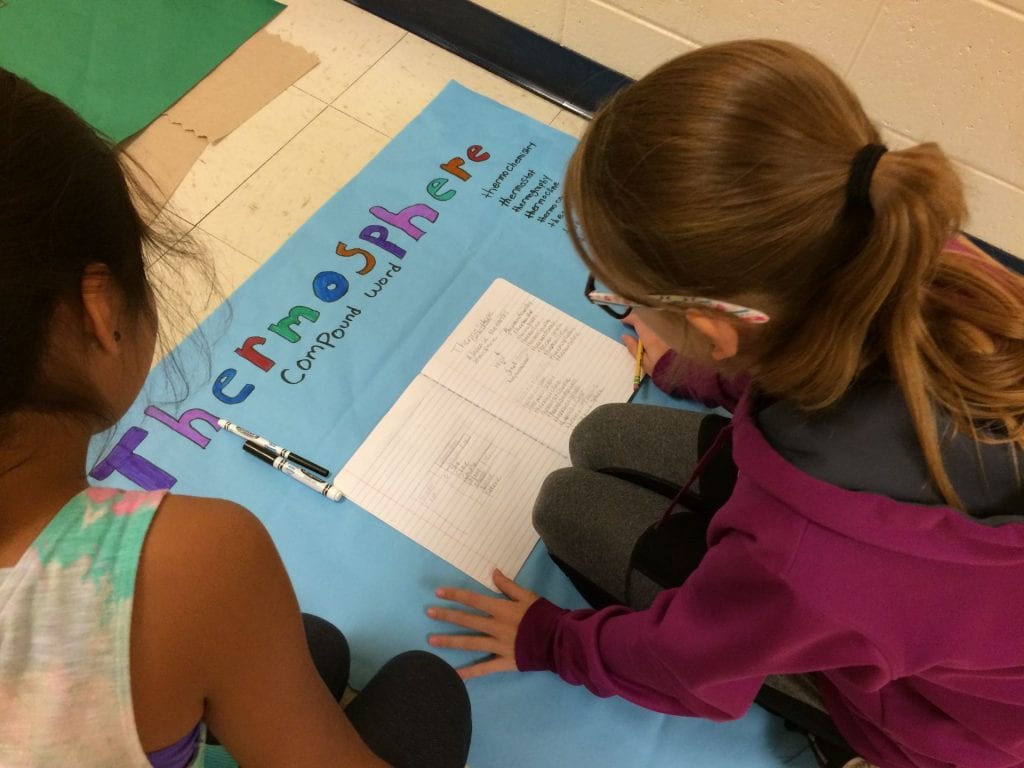

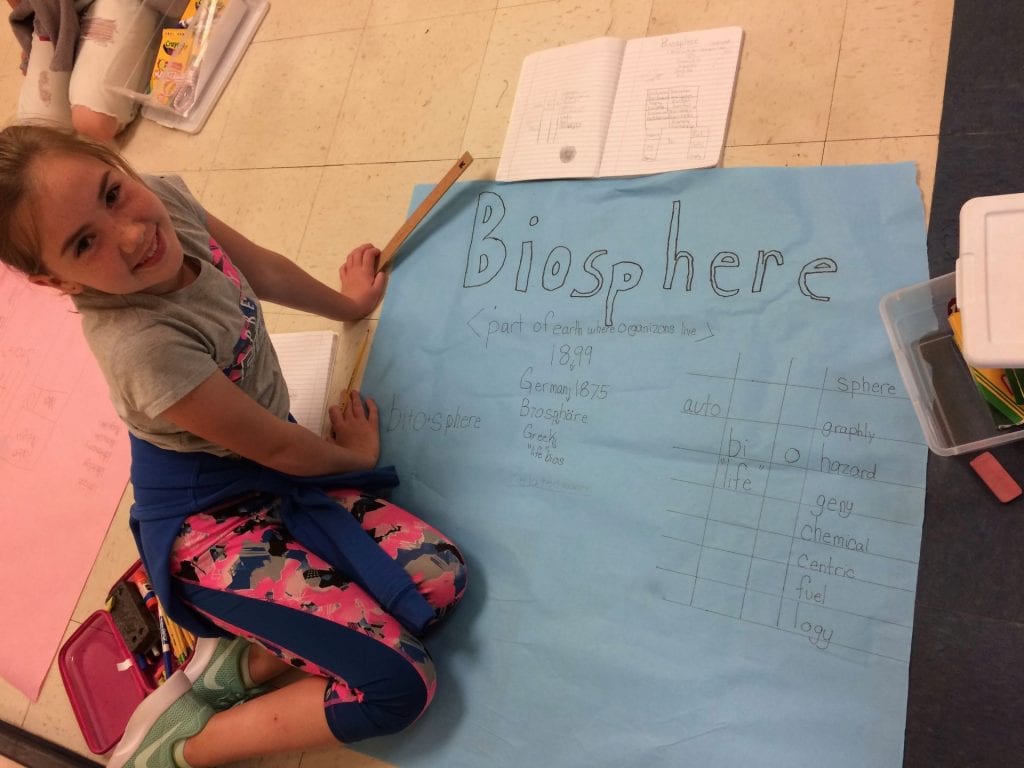

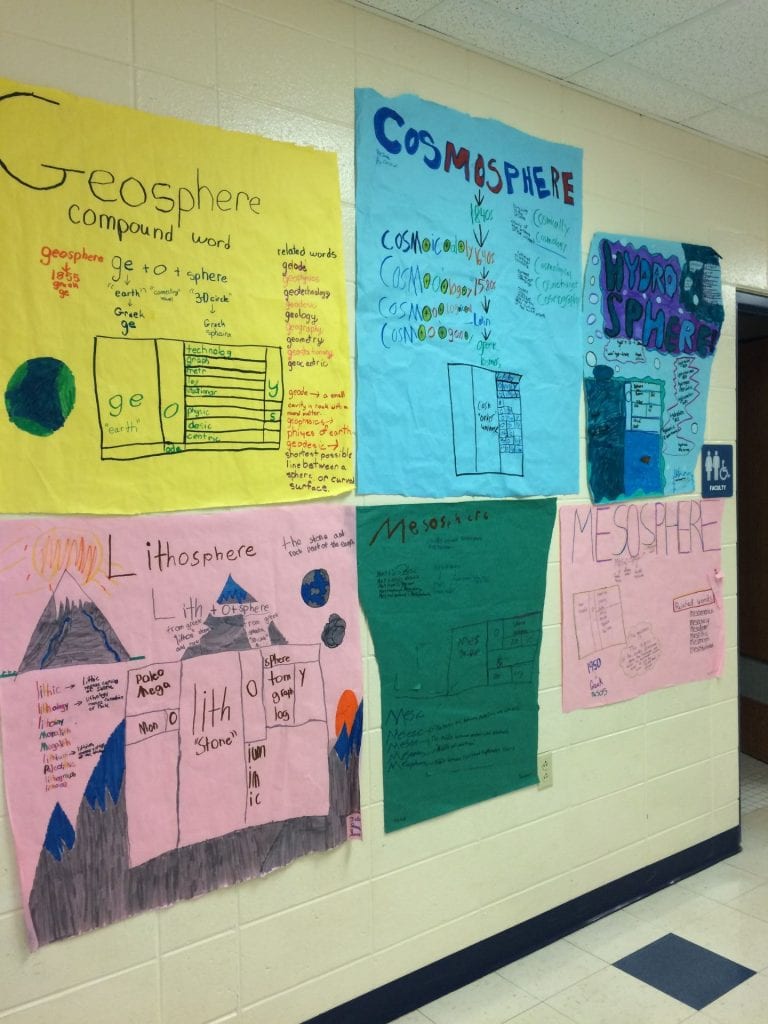

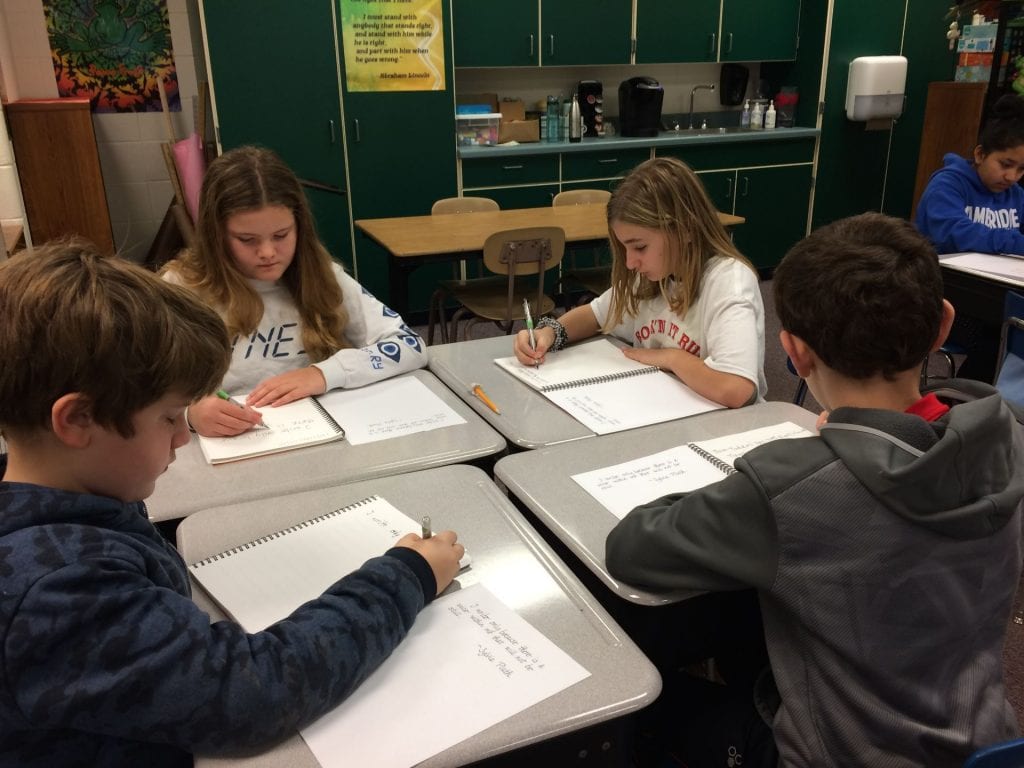

So now let me show you what I am doing with fifth grade words. We begin our science curriculum by studying the interactions of the biosphere, geosphere, atmosphere, and hydrosphere. As an orthographer, I immediately noticed that this group of words shares a structure. Focusing on that structure, I added lithosphere, troposphere, stratosphere, mesosphere, thermosphere, and cosmosphere to the list. I had the students investigate these words in small groups.

They are all compound words. You can see the familiar base <sphere>. Just in front of that base you’ll notice that each word has the connecting vowel <o>. That leaves a rather unfamiliar looking base at the beginning of each word. It looks unfamiliar because we have not been taught to recognize bound bases. A bound base is not found as a word on its own. It is always bound to another element in the word. When we think of compound words, we think of words like chalkboard or hallway. In those words we see two free bases joined together. In biosphere, we have a bound base <bi> joined to a free base <sphere> by the connecting vowel <o>. This <bi> is from Greek and has a denotation of “life”. The second base <sphere> is from Greek too. It has a denotation of “globe”. So the biosphere is everything that is alive on our globe or planet.

It is great to better understand a word by looking at its structure, history and the overall meaning we glean from paying attention to its elements. But if we stop there, we are only giving a student one more word to remember. Instead, looking at a word’s relatives is how a student makes connections to other words and how a word’s meaning becomes memorable. If we continue to look at <biosphere>, and focus on the first base <bi>, we can find words like <biographer> “someone who writes about other people’s lives”, <biohazard> “something that is dangerous to living things”, <biology> “the study of living things”, and <bioluminescent> “living organisms that emit light”. Do you see how all of these words are connected in meaning? If the students begin to recognize a base like <bi>, they will have a hint at what an unfamiliar word like <biometry> might mean. At the very least they will know it has something to do with “life, living”. If they also know the second base in this word (<meter>) has to do with measuring (geometry, diameter, speedometer, kilometer), they will put the two meanings together. They might still need clarification as to what it means to measure life, but a quick look at Etymonline will tell them that biometry is the calculation of a life expectancy. A biometrist tries to calculate how long something (under certain conditions) might live! Cool!

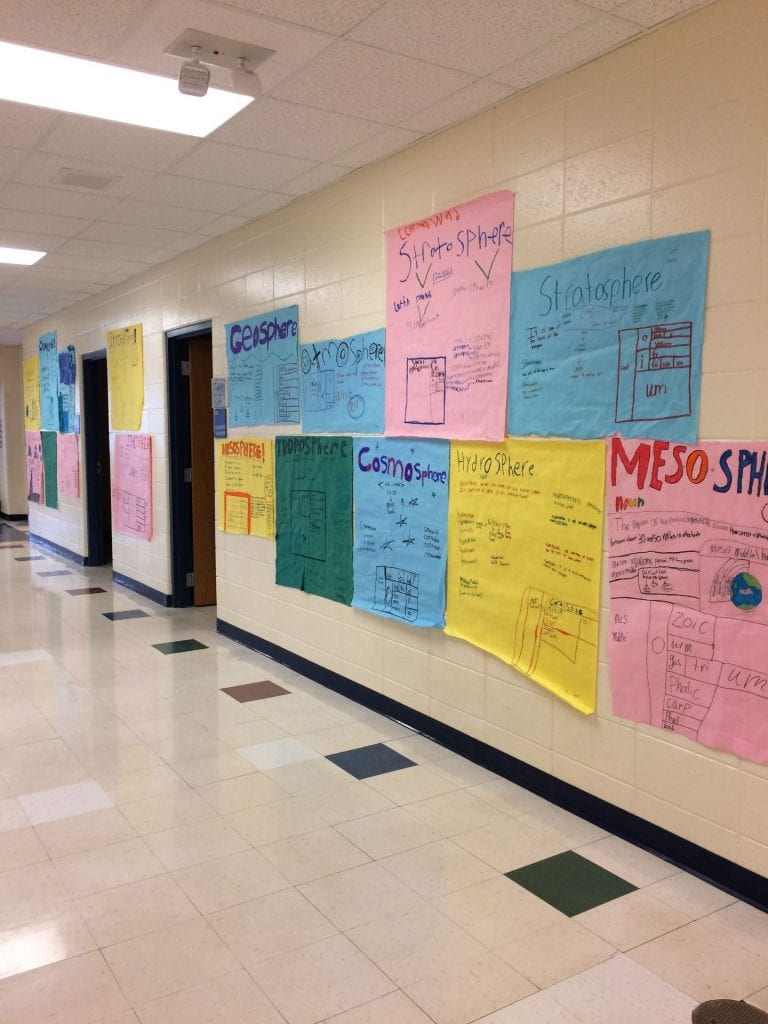

**At this point I encourage the parents to take a look at the posters in the hallway (once we have finished with the conference). The posters show the various investigations by the students. I feel it is important to also point out to the parents that when they look at the posters they should keep something in mind. It is not my intention for the students to remember all of the words they find. Rather, it is my intention for the students to realize how many words can be related to one base element and its shared denotation! Then, of course, the students also begin to realize that all words have structure (morphology), and a history (etymology).

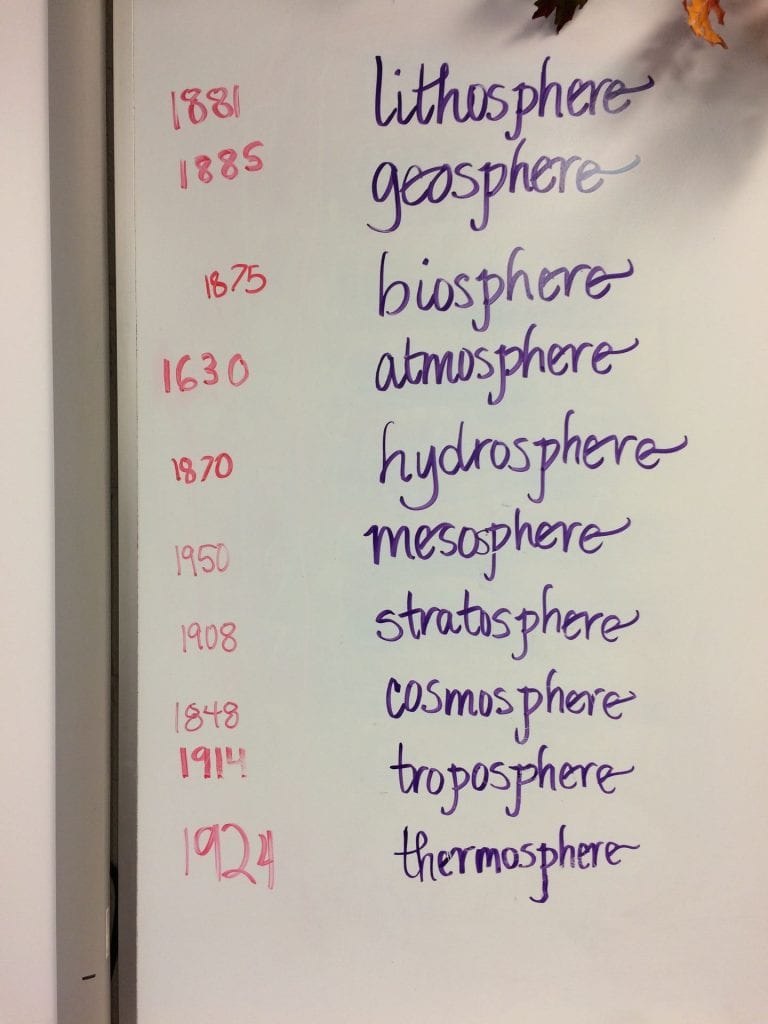

Next I showed parents the list of these words that was still on the whiteboard in the classroom. The students had written the year each word was first attested next to its corresponding word. It is my intention to have the students make a timeline to better organize the words and their attestation dates. Then we’ll be able to talk about which word was around first and which was created most recently. As it turns out, the word <atmosphere> was first attested in 1630. It is interesting that the oldest of these is <atmosphere> “gaseous envelop surrounding the earth.” It just goes to show how long scientists have been looking up and wondering about our atmosphere.

As the years passed and the technology became more advanced, scientists were able to detect differences in different areas of the atmosphere. It became important to be more precise in what they called things. I find it interesting that the specific layers of the atmosphere were named so recently. It began with the stratosphere in 1908, the troposphere in 1914, the thermosphere in 1924, and the mesosphere in 1950. You can almost imagine the scientists making their observations and then realizing that the atmosphere was actually made up of layers, each with unique properties. And as there was a need to fittingly name each layer, they looked to the classical languages (Greek and Latin) for appropriate elements!

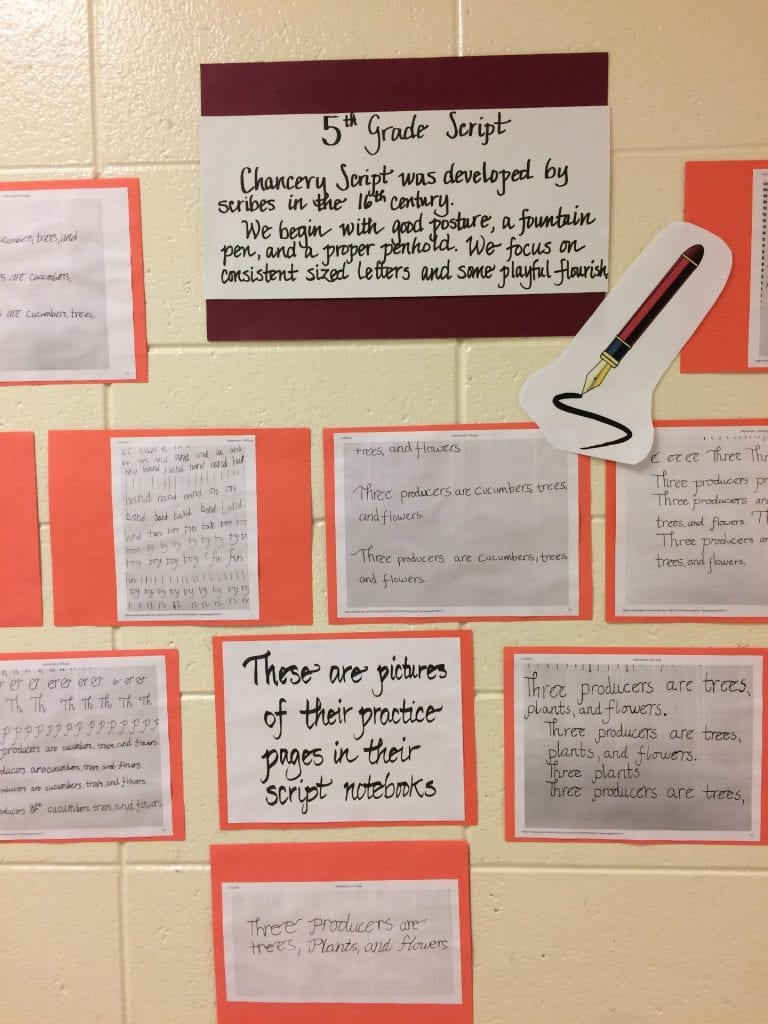

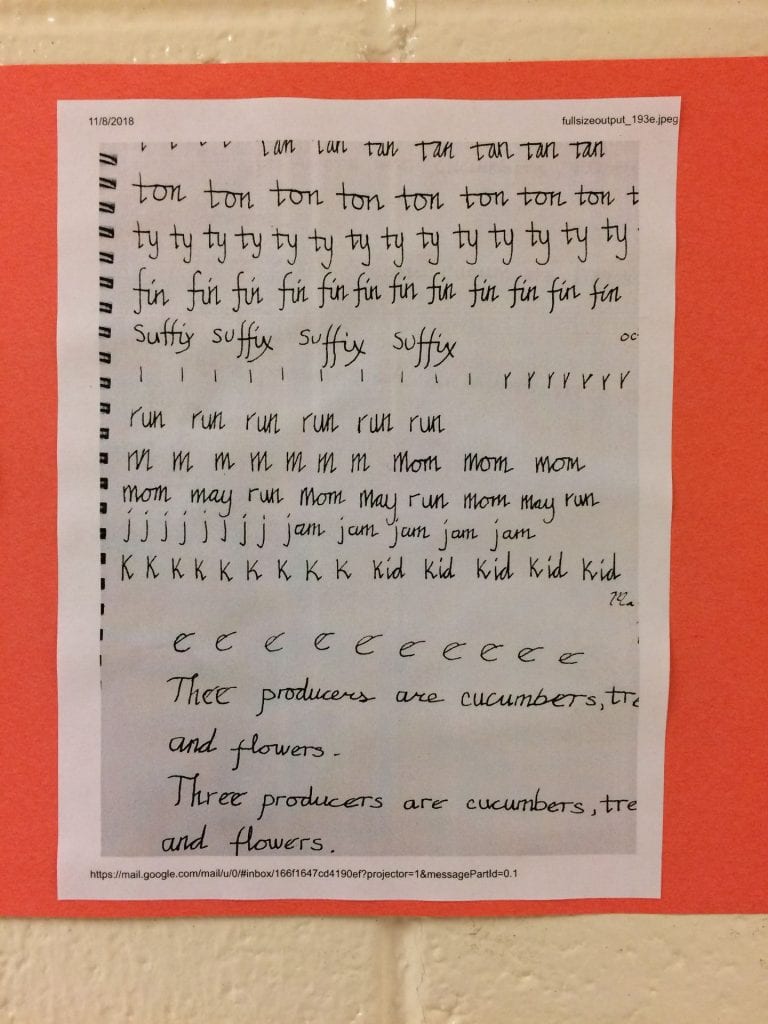

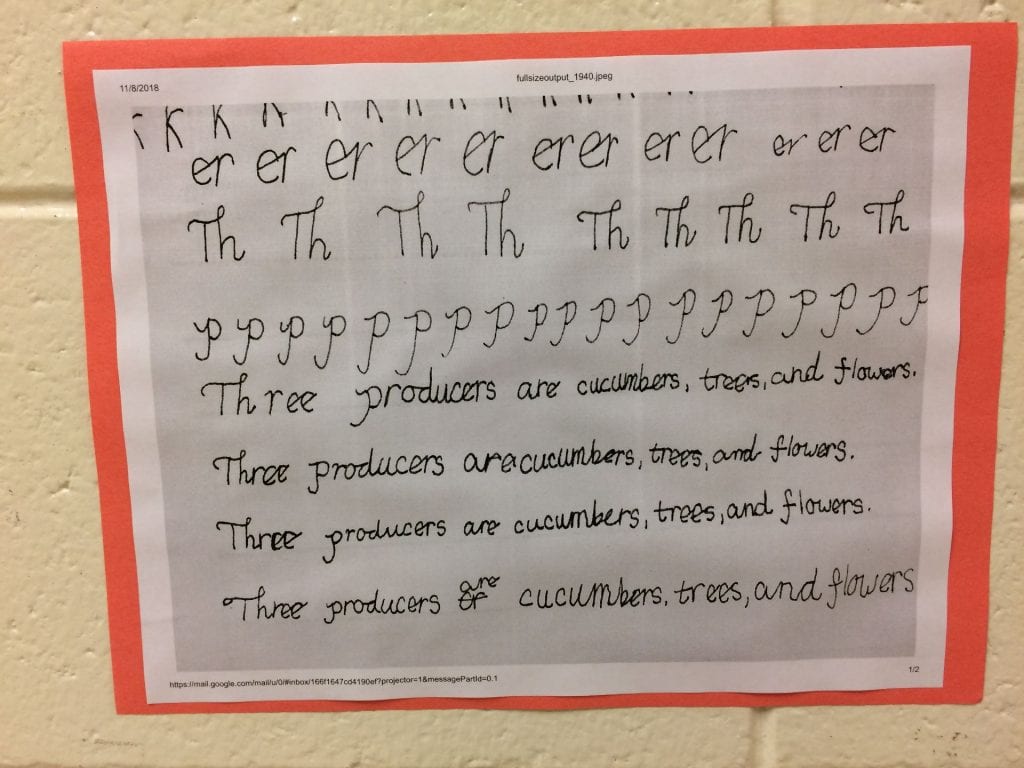

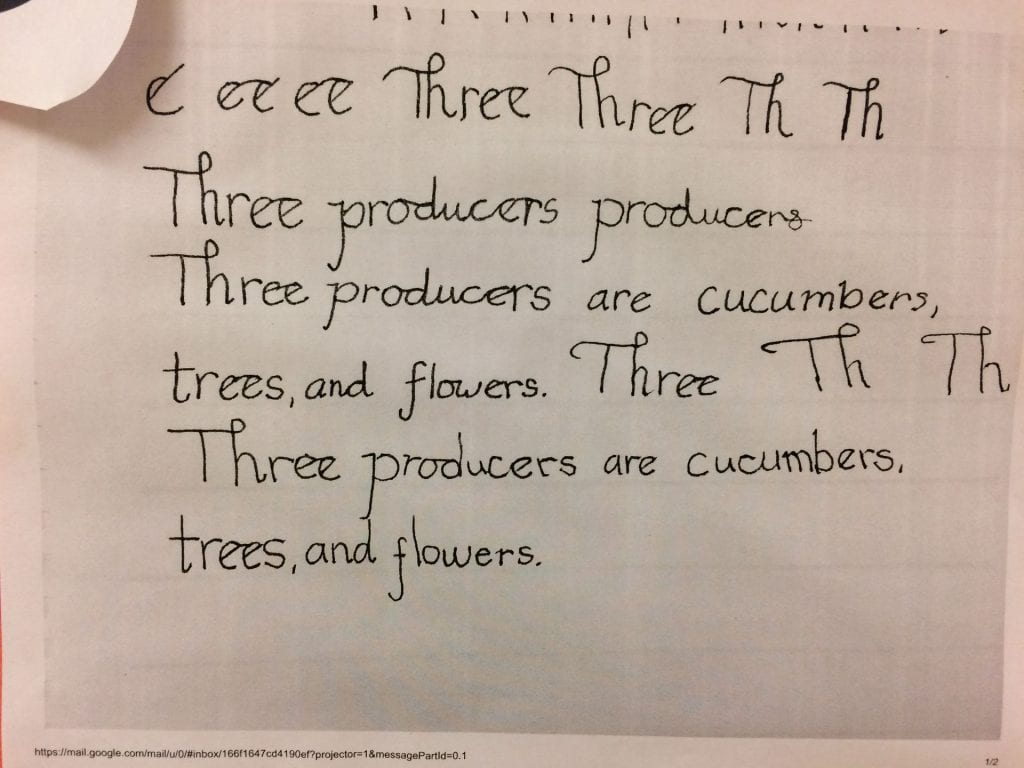

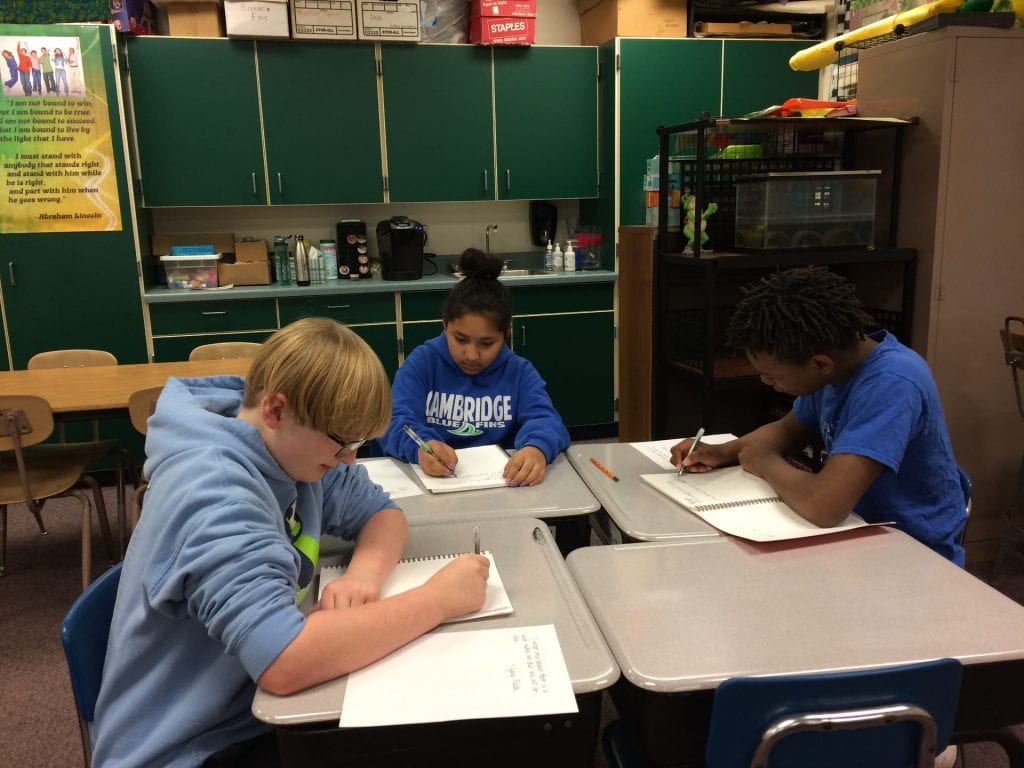

The next topic we discussed was the teaching of Chancery Script. My goal is for the students to have consistent and legible writing that also reflects their personal style. I have fountain pens that we use when practicing. We focus on writing posture and a comfortable pen hold (as opposed to a tense grip). Again, I direct the parents to stop on their way out and see the examples I have posted in the hall.

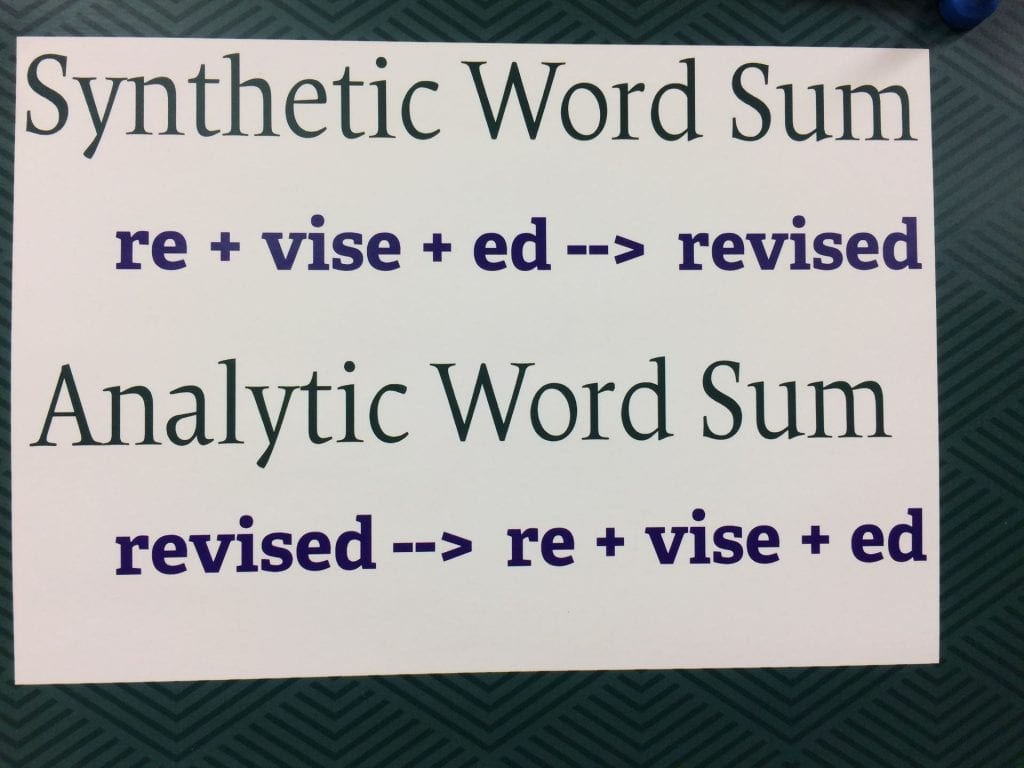

When I moved on to what the students were learning in science, we ended up weaving in orthography once more! As we’ve taken a closer look at the biosphere, we’ve learned about food chains and food webs. The Photosynthesis Play we recently performed for the school, gave us a good start in understanding that the sun provides the energy for photosynthesis. In fact, the word <photosynthesis> means “put together with light”. It is the Greek base <phote> that means light. We see this base in photography, photojournalism, photocopy, and phototropism (since we’ve studied the word <troposphere>, we know that phototropism has to do with a plant turning towards the light). We have also studied the word <synthetic> and we use it often when we write synthetic word sums. We know that a synthetic word sum is one in which we put the elements together to form a completed word.

Because of our previous understanding of the words <synthetic> and <phototropism>, we could more easily understand that <photosynthesis> would be a combination of those meanings “put together with light”. Quite by coincidence, a few days later we were watching a video that further explained food webs and trophic levels. The narrator in the video spoke about photosynthesis (the process in which a plant produces its own food), but then added that some bacteria are too far from the sunlight’s energy, and so produce their own food using chemosynthesis. Without skipping a beat, several students raised their hands and excitedly explained that chemosynthesis would mean “put together with chemicals!”

I love presenting words to the students that I know they will be unfamiliar with, but that share a base we have talked about. In this way, I am teaching the students to look for familiar elements in a word. Of course, I also teach them that while creating a hypothesis about a word’s structure is a great thing to do, checking a reliable source to confirm or falsify that hypothesis is a responsible habit to form! To this end, we use many etymological and regular dictionaries on a daily basis.

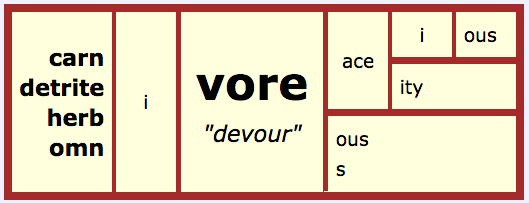

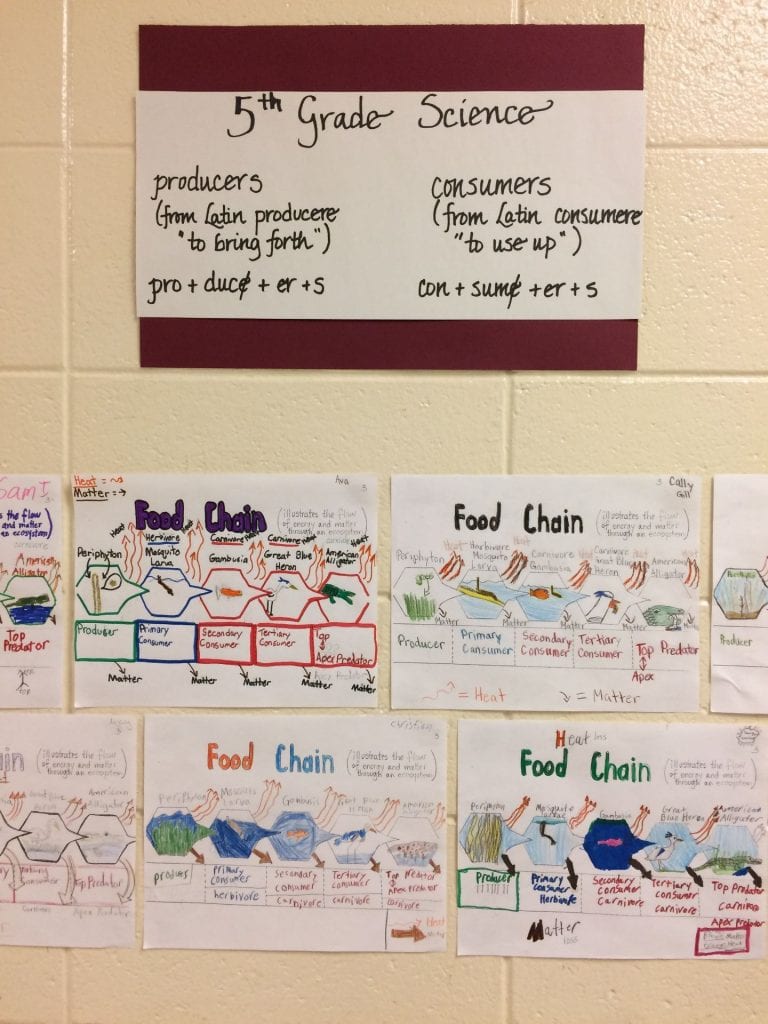

The study of food chains, food webs, and trophic levels exposes the students to many great words and word families. If the organism makes its own food, it is a producer. If it eats the producers, it is an herbivore. If it eats an herbivore, it is a carnivore. If it eats both producers and carnivores, it is an omnivore. If the organism has no natural predators, it is a top predator. If it is not a producer, it is a consumer. If it eats an organism’s waste, it is a detritivore. If it helps break down a dead organism it is a decomposer.

So how do I help my students understand those words when there are so many? We look for related words. We look at their structure. We look at their histories.

This first matrix shows how carnivore, detritivore, herbivore, and omnivore are compound words and share a structure. They also share the base <vore> “devour”. As you can see, the words voracious and voracity are also represented on this matrix. The students may not know these words, but it makes sense to introduce them as other members of this family. It deepens the connections being made. I might even ask them to name a time they had a voracious appetite!

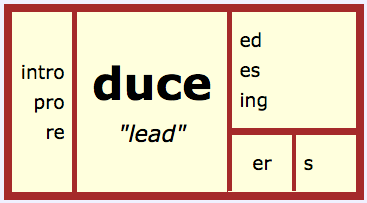

In this matrix I’ve chosen to include three related words (with options for suffixing). I am illustrating this base in other words besides the one we are focusing on in our study (producer), but I choose not to overwhelm the students with too many unfamiliar words this time.

In this matrix, I am sticking to one word and its suffixing options. I use a matrix like this to practice the suffixing convention of replacing the single final non-syllabic <e>. I also use it to point out that suffixes can have grammatical functions.

As we are finishing up our time together, I once again point the parents to the display that is up in the hallway. It shows our work with food chains and the terminology being learned.

***The parents were very interested to know what their child was learning. Several expressed their own frustrations with spelling, and wished they had been taught these things. A few with younger children were hoping that other classrooms were teaching orthography as well.

Just before getting up to leave, one mom turned to me and said, I have something I just have to share with you. I think that because of what you’ve been explaining about orthography tonight, I finally understand a conversation I had with my older daughter (the one that was in my class three years ago).

My daughter and I went round and round a while ago. I was asking her how to spell a word. She said, “What does it mean?”

I said, “I don’t know.”

She said, “I can’t tell you how to spell the word if I don’t know what it means.”

I gave her a surprised look. “What?” I said, “I never knew what words meant. I just memorized how to spell them.”

She looked back at me even more surprised. “That makes no sense! You need to know what it means before you can understand how to spell it!”

That just made my day! Spelling represents meaning. My former student knew that, but her mom didn’t get it until this conference night. I’d say it was a night well spent!

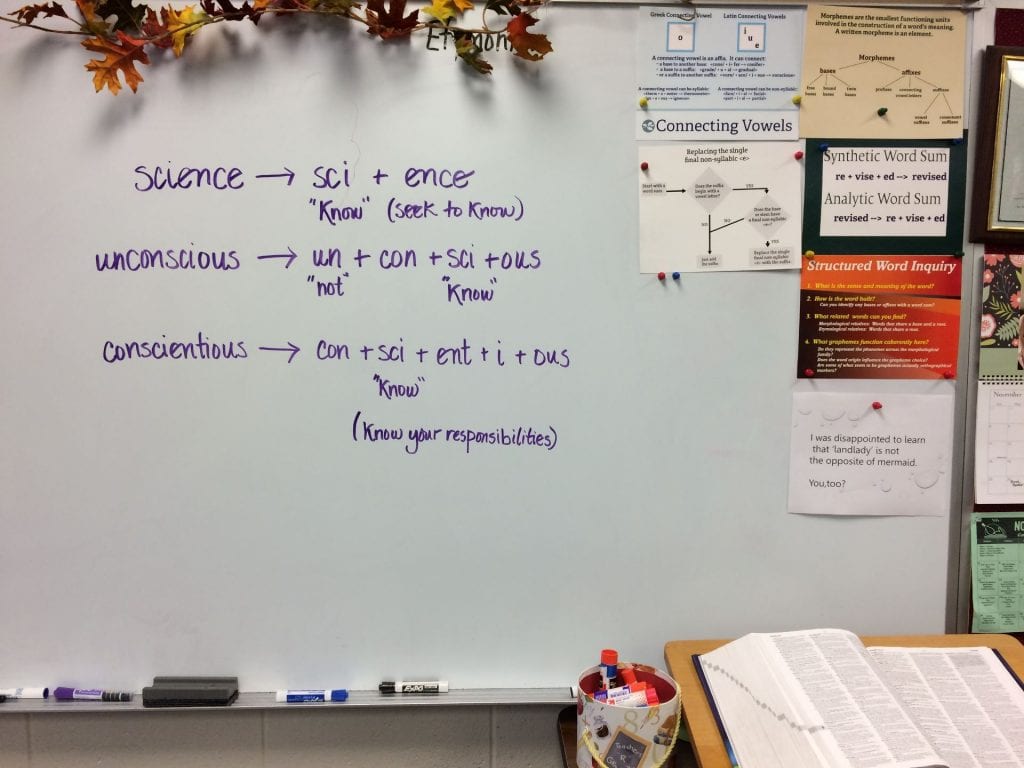

Here’s a final touch. I had this on the whiteboard at the front of my room just in case anyone stopped to take a look.