I love teaching grammar. No, really! I love teaching grammar. Of course, I didn’t always love it. I began loving it when I met Michael Clay Thompson. He revolutionized the way I was teaching it. It’s hard to imagine something other than what I grew up doing – going through each part of speech as laid out in our English textbook with plenty of fill-in-the-blank sentences, in order to prepare for a test on things learned in isolation. But Michael Clay Thompson thought of a different way to teach it, and his idea is brilliant!

He encourages teachers to review/teach the parts of speech and the parts of a sentence within the first month of the school year. That sounds crazy, yes? That does not leave enough time to teach to mastery, but that’s okay. The mastery happens later on, after the sentence analysis starts. You see, after that first month of intense review and teaching, I start writing sentences on the board to be analyzed. And we spend the rest of the school year understanding the interrelationships and functions of the parts of speech, the parts of the sentence, and the phrases because we see them over and over in different sentences as they are being analyzed. In other words, we spend one month of reviewing/learning and 7-8 months of applying what was learned. See? Brilliant!

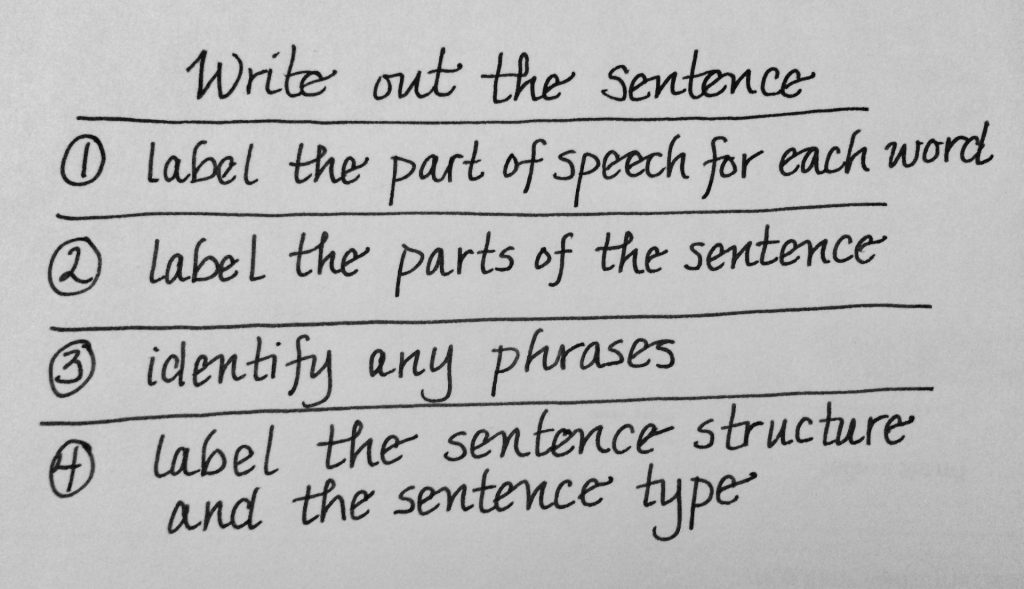

To begin with, the sentences are simple and short. But the analysis is the same:

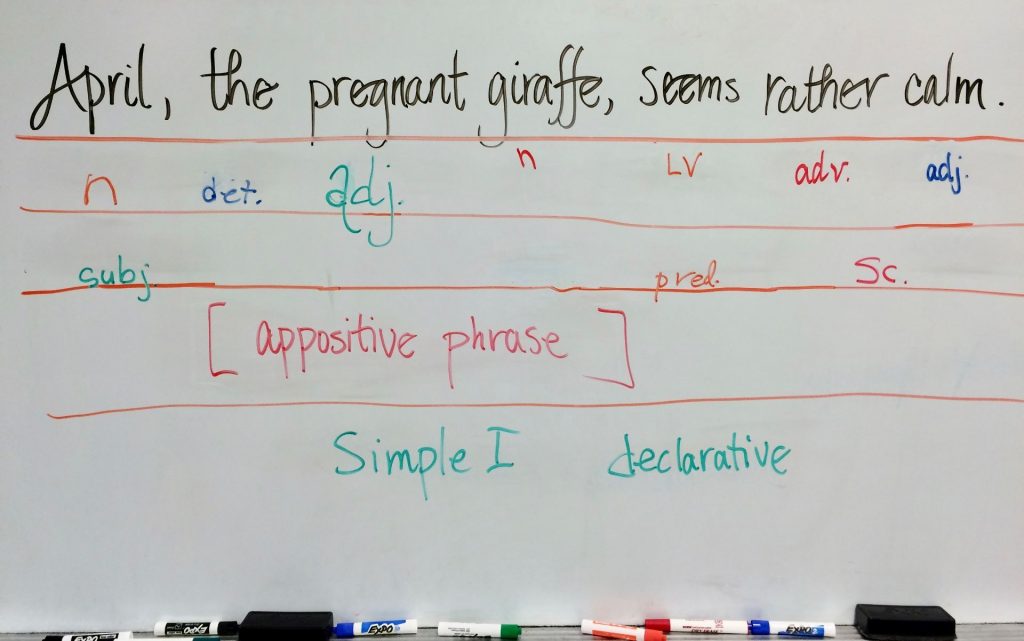

Now here’s what that looks like with a real sentence:

The first row below the sentence is parts of speech. If you are wondering what ‘det.’ stands for, it is an abbreviation for determiner. Over the course of the last year, I have come to understand and embrace the idea of a ninth part of speech – that of the determiner. Prior to that, I had, like a lot of people, considered articles to be a type of adjective. But identifying a determiner as a word that begins a noun phrase has been especially helpful to my students. When they spot a determiner (and because of their frequent use in sentences, this is one of the first parts of speech students become confident about identifying) they know that a noun (or pronoun) will follow. It may be the next word, or it may be after one or more adjectives (or adjective with an intensifier), but it will be there!

Articles (definite and indefinite) are not the only types of determiners we see. Other types include quantifier, possessive, interrogative, and demonstrative. Identifying determiners in our sentences has given my students a predictable pattern to look for. The noun phrase usually begins with a determiner and ends with a noun or pronoun. In between those two we might see adverb-adjective pairs, adjectives, or nothing at all. There is also the possibility that a determiner won’t be used, as is the case with some noncount nouns.

Other than the abbreviation for determiners, I imagine you can figure out that ‘LV’ stands for linking verb. In the second row, the important parts of the sentence are identified. Because this sentence has a linking verb, we look for a subject complement (calm). If the verb was an action verb, we would look first for a direct object and secondly for an indirect object.

In the third row, we identify any phrases. This sentence has an appositive phrase. In the last row we identify the sentence structure. This sentence is a simple sentence with one independent clause. The word declarative identifies the type of sentence this is.

In a nutshell, my example above illustrates the four level sentence analysis my students and I engage in for 7-8 months of the school year. Can you imagine how comfortable some of this feels by the end of the year? They have the opportunity to keep making sense of the order of words in sentences! They have the opportunity to keep making sense of the functions and interrelationships of words in these sentences. They begin to realize that the function of a word within a sentence determines its part-of-speech label. I particularly love it when a sentence contains a word that is able to function as more than one part of speech and the students need to reason out what its particular function is in the sentence before them! They become so invested in figuring it out!

But a bigger benefit to all of this is what happens when I conference with the students about their writing. I can address specific aspects of their writing using specific language that they now understand. A typical comment from me might be, “You have a dependent clause here, but remember? A dependent clause is not a sentence on its own. It needs an independent clause either in front of it or behind it to complete the thought.” I might also say, “You have written a pretty terrific complex sentence, but it is missing its comma. Begin reading it aloud and tell me where the comma should be.” The students understand what I am saying to them and feel good about being able to make fix-ups so easily.

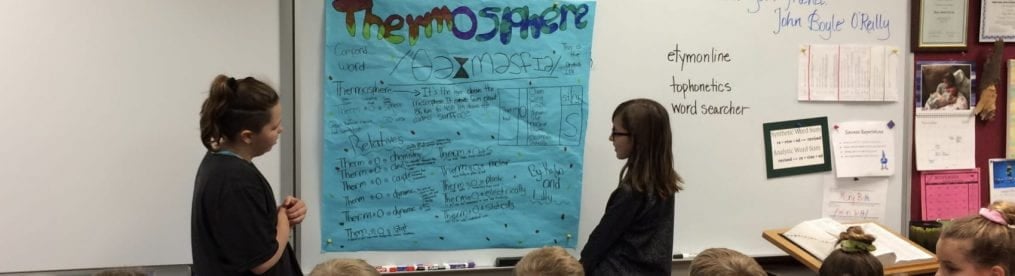

This is what it looks like as students are actively analyzing a sentence:

So this is obviously scholarship, but what does it have to do with Structured Word Inquiry? Yesterday I came across a recent article by Michael Clay Thompson. It was posted at Fireworks Press where you can find all of the Language Arts curriculum materials he has written. Click HERE to check it out. The title of the article is “Doing four-level grammar analysis is like practicing your piano”. In the article, he addresses why students need to continue analyzing sentences at every level, even if they’ve already been doing it for several years.

In my situation, students are analyzing sentences for the first time. The benefits are obvious. But what about next year and the year after that? When is enough enough? I sincerely hope you spend the time reading his response. To that end I will not post the highlights of it. If I tried, I’d have to post the whole article anyway! I will, however, share two of his thoughts because they philosophically parallel how I feel about my other passion, Structured Word Inquiry.

“Four level analysis is different because it is an expansive-almost cosmic-inquiry into language, with four tendrils of inquiry moving forward simultaneously, and it is investigating something that is not concrete or simple but that is essentially bottomless.”

For those familiar with SWI, do you see the parallel? As I’ve been teaching my online class, Getting a Grip on Grammar, I’ve been realizing more and more how similar the investigations into these two areas can be. I love thinking of SWI’s four essential questions as well as MCT’s four-level analysis as “tendrils of inquiry moving forward simultaneously”. And clearly neither is “concrete or simple”, but “essentially bottomless”. There was a time when I would’ve thought of that as an overwhelming idea – thinking I would be expected to know all of it at some point. But scholarship isn’t like that.

Scholarship is not what happens when you use a textbook, memorize definitions, and get tested. Scholarship is done leisurely. It is a continual pursuit to understand better what one only understands partially. There is no test. There are only questions to be posed, investigations to be launched, and evidence to be gathered. Here I will share another quote from Michael Clay Thompson’s article. In your mind, replace ‘Four-level analysis’ with ‘scholarship’ because clearly the one is a form of the other.

“Four-level analysis can lead you through the known, beyond the terms, past the things that have already been named, and on out to the edge, where the wild questions are.”

It’s alright if you read it a second time. Because of my passion for both SWI and grammar, this sentence not only resonates with me, it also makes me smile! Scholarship is a worthy pursuit, whether it be in regards to words, grammar, or in playing the piano. Thank you Michael Clay Thompson for the beautifully written, inspirational article!

**If you are interested in learning more about the grammar instruction my 5th graders receive, there is a tab at the top of this page that says “Grammar Class”. That is where you can find out about current schedules. If there isn’t one currently scheduled, just let me know your preference for time-of-day and dates. I will created a new schedule!