Picture courtesy of www.willstevenphotography.com

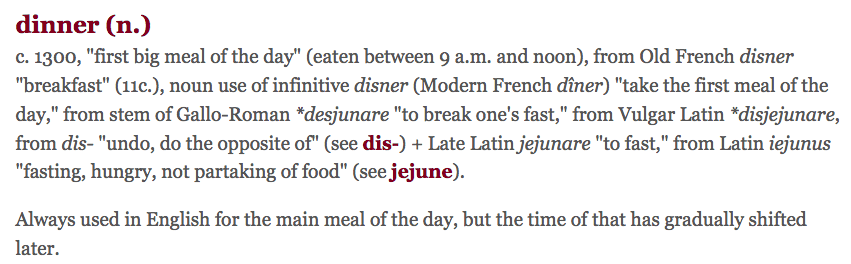

When you begin to learn what is real about English spelling, you also begin to swim against the current in an educational world that has been led to believe that reading is simply the act of unlocking a code – that code being the letters of our alphabet. In many such programs, teaching reading means beginning with isolated spoken sounds and matching them to written letters. That is followed by practice at “sounding it out.” The newest buzz word for this is “orthographic mapping.” The student is taught to attach a pronunciation to groups of 1-4 letters. These letter groupings are somewhat consistent, but there are a lot of them to know to automaticity in order for a child to read fluently. If “sounding out” a word can’t make it recognizable, it is deemed “irregular.”

Those in the front lines (tutors, interventionists, and teachers of pre-k, kindergarten, 1st grade, and 2nd grade) who have received intense training in these phonics-first models or have grown up in a system using these models, seem to struggle the most in imagining a world that begins with meaning and then considers morphology, etymology, and phonology as interrelated in explaining a word’s spelling. Interrelated. Not one first in isolation, but the three facets of a word coming together to explain its meaning, spelling, and pronunciation. In this way the student is presented with a system right from the start. They are not taught specific strategies for reading that are then misapplied to writing. They are not taught that English spelling is crazy or that it cannot be understood. Instead the students learn from the start how speaking, reading, and writing can be used to represent our thinking. Much of the system we have is logical and predictable. (Many of the suffixing and other conventions are predictable. Learning that words are built from bases and that the spelling of bases within a morphological family is consistent is logical.) Students learn how to question what they do not understand. In fact their questions are encouraged and even celebrated, sending the underlying message that asking questions is key to learning. They are taught to see meaning relationships between words that share a base element, and that even when the pronunciation within that word family shifts, the spelling doesn’t. They are taught that all words have a structure, a spelling, and a pronunciation that can be explained and understood.

When first hearing about Structured Word Inquiry, many trained educators who have experienced the gamut of “spelling programs extraordinaire” figure this too is full of promises it can’t fulfill. And when they hear there is no scope and sequence, they get downright jittery. How in the world will they know what to say and what to teach without a teacher guide to tell them? But that’s just it. Structured Word Inquiry is NOT A PROGRAM. It is a course of investigation driven by curiosity. Rather than a list of words to learn each week, there are principles to visit and revisit via words chosen that enhance curricular content, are someone’s personal favorites, or are suggested for any of a number of reasons. There is no teacher manual full of answers because an answer to every question is not what I want my students to expect.

Ponder that for a moment.

There is no teacher manual full of answers because an answer to every question is not what I want my students to expect.

In the education world, when a question is posed, everyone searches for an answer. They stop when they get one they are satisfied with, and the conversation moves on. But, especially in the sciences, don’t we accept that answers are temporary? That at some future time, some scientist may discover a different answer to the same question? A deeper understanding? THAT is the same mindset I use when teaching Structured Word Inquiry. Sometimes I refer to it as Scientific Word Investigation, which more appropriately represents the scientific rigor and evidence-based thinking that is integral to this.

Unfortunately, we live in an educational world in which most people have stopped wondering about a word’s spelling and have just fully accepted that our language has no rhyme or reason to it. The teachers think they are teaching how our spelling system works, but if they are really really honest with themselves, they will admit that they wish they could explain the spelling of words like of, come, have, does, they, laugh, give, the, and countless others that end up on Word Walls in far too many classrooms. Every year a child is in school, they encounter more and more of these words that the adults only know to shrug their shoulders at, reinforcing the idea that English spelling is crazy. It is amazing to me that we all accept (and yes, I accepted it too for many years) the idea that there is no explanation to be had for words that can’t be sounded out.

But why is it like this? Why aren’t the explanations accessible to teachers? Why have teachers been told instead to use “rules” that don’t statistically work? Not only am I referring to the old “I before E” rule, but also to the “Two Vowels Go Walking” rule. Did you know that the “i before e” part of that rule is only accurate 75% of the time? Or that the “except after c” part of that rule is only accurate 25% of the time? Or that when looking at the top (meaning most common) 2,000 words, the “when two vowels go walking” rule was found to be accurate only 36% of the time?

Here are two more “rules” that deserve to be banned. The first says, “When a stressed syllable ends in e, the long sound of the vowel is used, and the final e is silent.” It works for words like bike, pope, and rake, and doesn’t work for give, love, and move. Teachers will find it surprising that it is accurate only 68% of the time. (Those teaching with SWI will recognize a different way to explain what is happening there – it has to do with the function of the single final non-syllabic <e>.) The second rule says, “When there is only one vowel in a stressed syllable and the vowel is followed by a consonant, the short vowel sound is used.” This works for fix, hop, and cat, but not for mind, wild, and fold. This one too works only 68% of the time.

I find it astounding that creative people have used their talents to come up with these “rules” instead of demanding to understand why words are spelled the way they are! Is it really that there is no explanation? Hardly. Are the explanations really so complicated that teachers and children alike can’t learn or understand them? Again, hardly.

In my opinion, the three biggest problems are these:

ONE

The inaccuracies have been embedded in the teaching for so long that as a society we have become complacent. There is a general acceptance of the notion that English spelling is crazy and can’t be understood. We see this all over the internet. People print what they perceive to be the ridiculousness of English spelling on coffee cups and T-shirts, and everybody laughs. People offer proof of the craziness of English spelling by asking why ‘bomb’ doesn’t rhyme with ‘tomb’ or ‘comb’. But who said they had to? You can blame that expectation on teachers who first taught those people to read. They may not have said it specifically, but after having students complete worksheet after worksheet with cat, rat, sat, pat, tip, sip, rip, lip, and cup, sup, pup, children get the message. Words that have the same letter string will always rhyme. And no one ever tells them differently. Children learn what you tell them, but also what you imply.

TWO

Teachers cannot teach what it is that they themselves do not understand. This lack of understanding is so pervasive because there are very few colleges that equip teachers with orthographic understanding. The textbooks offered to future teachers of reading are smattered with the inaccurate rules listed above. It would be difficult indeed to sort out what is worth using with children and what is not. And the curricular materials school districts spend millions on every year are no different. Many teachers can sense that the materials are not helping their students, but don’t know enough on their own to understand specifically what parts are utter nonsense. All the company has to do is slap the words “evidence based” or “research based” on the cover, and the school districts are all in. No one in any of those districts is reading any of that “evidence” or “research” and the company counts on that. The companies simply put a new spin on the old content and market it. School districts see where there are weaknesses in their ELA scores, and want to find something that will help their teachers improve scores and ultimately assist their students in becoming better at reading and writing. They believe the companies know what they are doing. But those administrators, like the teachers, like the teacher-prep colleges, and like the curricular material companies don’t understand English spelling themselves. The curriculum companies get as creative as they can in presenting spelling as a fun activity, but the bottom line is that one cannot teach what one doesn’t understand.

THREE

Many children will learn to read even without understanding how our spelling system works. This is what keeps so many spelling programs and curricular materials in business. It is also what keeps so many well meaning teachers and their students in the dark. If a child can read, then what does it matter whether or not they understand a word’s spelling? There will always be spellcheck, right? This idea that reading is primarily about sounds represented as letters may seem to be so obvious when a child is learning to read. But as they advance through the grades and encounter longer and more interesting words, their missing understanding about the morphology and the etymology that affects the phonology is the thing that becomes obvious. Why don’t they know that some letters are etymological or orthographic markers, or that a word’s etymology has much to do with the graphemes that spell it? Why weren’t they taught that English spelling is a system and that each year their understanding of that system could grow to accommodate any newly acquired words? Instead it is assumed that if they learn to read in kindergarten and 1st grade, they will naturally maintain that reading proficiency and spelling proficiency automatically as they move through grades, even when the materials used include inaccurate information such as I’ve mentioned above.

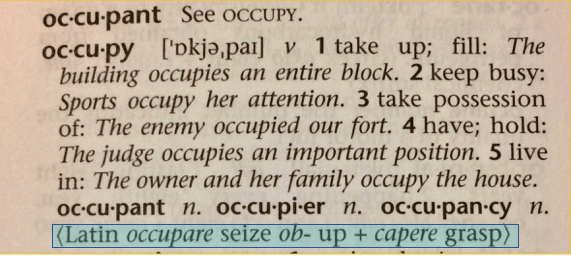

An example of such nonsense was recently brought to my attention by a teacher using Words Their Way. Her students were asked to spot the <un> in unplanned, unprepared, unlock and uncle. Really? The <un> in three of those words is obviously a prefix. Why would ‘uncle’ be included here? Are the students supposed to think it also has an <un> prefix, or is this just an indicator that children are not being taught that a word has structure (is comprised of morphemes)? Then, within that same week, the same teacher told me about the task in which her students were supposed to spot the <re> in rethink, replay, reheat and reptile. She wondered what she was missing. Was there an <re> prefix in ‘reptile’? Of course not. This teacher was not missing anything, but her students sure were. They were missing the framework by which to understand the words they were being asked to read and write. They were missing being taught the structure (morphology), history (etymology), and using both of those to understand the pronunciation (phonology) of words. They were missing feeling comfortable to ask questions about things that don’t make sense (whether or not the teacher has a ready answer). The fact that students no longer ask questions about spelling by grade 4 should be a big red flag to teachers everywhere. Sadly it isn’t. The students have learned that the teacher won’t be able to answer or guide them to resources that would help anyway. They have no expectation that English spelling will make sense. That is sad. It doesn’t need to be that way.

My students don’t deserve to be limited by the boundaries of my own understanding.

As teachers, we often feel more effective if we can anticipate the questions our students might ask and be ready with an answer. When we can successfully do that, we feel knowledgeable and think we are presenting ourselves as knowledgeable to our students. But there’s a catch to all that. In many instances teachers create a façade of having background in content knowledge. They have learned to rely on a teacher manual more than they rely on their own professional expertise. I don’t really want my students believing that I know everything or that I have all the answers. There are only a few students who would be brave enough to ask a question in that situation. Most fear looking “stupid” by asking a “stupid” question in the presence of someone who appears to be an expert, whether or not that is actually the case. If you’ve ever found yourself wondering why your students don’t ask more questions, perhaps you have set up this atmosphere without realizing it.

Here’s an example of a well meaning teacher who tried to limit her students to her own level of understanding. Each year I coordinate a Science Fair at our school. I’ve been doing it for years. (The simple reply to why I do it is that there are always those students who shine at the Science Fair in a way that is unexpected by adults/peers in their lives. Those adults could be adults at school who only see certain aspects of the student (math, reading, behavior issues, etc.), or they could be extended family or neighbors.) Anyway, one year there was a colleague who was guiding her own students through the process of getting ready for the Science Fair. She approached me and asked if we might change the scope of the Fair just a bit. Because she didn’t feel particularly knowledgeable about many areas in science, she was suggesting that we choose ten topics. The students could then pick one of those topics for their Science Fair project. In this way, she could anticipate questions and most likely be able to answer them as the students progressed through the weeks of experimenting. It would make participating in the Science Fair more comfortable for her.

As much as I understood why she was asking this, I couldn’t agree to it. It might eliminate the possibility of a student following a passion or interest. We all know what happens when a student is forced to pick a topic they are not interested in. That is not a way to encourage curiosity and creativity. When one of my students picks a topic I have no background in, I tell them how excited I am that we will both be learning about the topic. In fact, I find myself asking lots of questions when the student and I journal. (Since I am now the lone science teacher at our grade level, journaling is how I communicate individually with the 75 students I currently prepare for the Science Fair.) My own curiosity is aroused when a student picks a project or wonders about something no one else has picked or wondered about in the last 25 years of Science Fairs! Instead of limiting the students to my own background knowledge, I embrace stretching my background knowledge to include something new, and I model the enthusiasm that goes along with learning! It is very similar to how my students and I study the English spelling system.

My students and I find a sense of relief in the freedom that comes with not having to have the one right answer to every question. And yes, I included myself there. I never realized the “must know the right answer” burden I was carrying until I began investigating words. Since that day, I have moved forward as wide-eyed and curious as my students. I have experienced the joy of scholarship, and that has fueled a passion for desiring to know more. My students see me as someone who has a deeper understanding than they do, but also as someone who is eager to learn more. I make a big deal when a student asks a question I never thought to ask about a word or about a spelling. I make an even bigger deal when it is a great question that I don’t know the answer to. Just as in my Science Fair example, I am excited to know that the student and I will both learn something useful! My students are fully aware that I don’t know everything about English spelling. I am not setting up any false illusions about that. Yet we all understand that I am in the best position to guide the inquiries until they learn the process for themselves. And that is my goal – to teach my students how to use SWI on their own to deepen their understanding of the words they wonder about.

Here’s another example of a teacher whose students are limited in their learning by the teacher’s background knowledge. This is something I read on a blog the other day. The teacher is a kindergarten teacher who is teaching her students to read. She is enthusiastic and sincere in wanting her students to succeed. The task she describes is that of teaching sight words. First she says the word in question. Then she has them isolate the sounds they hear. Then she shows them the letters that represent those sounds by writing them on the board (orthographic mapping). She begins with the letters that represent a pronunciation that is predictable. Then she unveils the letters that represent a pronunciation in a way that isn’t expected.

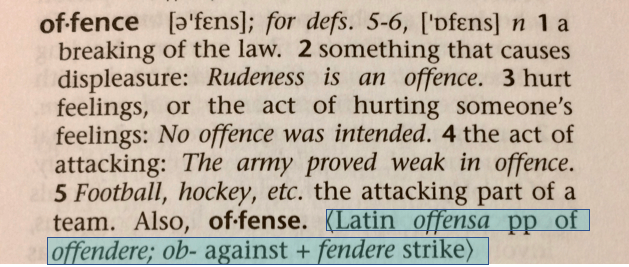

“Sometimes I like to get a little dramatic as I unveil the word. -Especially for really irregular ones…my students died laughing when I revealed the spelling for “of” and showed the shock and craziness of the word with my expressions.”

If she herself had an explanation for the spelling of <of>, surely she would offer it. Since she doesn’t, she teaches her students that English spelling is often worthy of shocked looks and crazy expressions. When I asked why she embeds this rather unhelpful implication in her teaching of reading and writing, she defended it by saying that it made the sight words memorable and that the learning was fun this way.

Now I completely understand the idea of making learning fun and memorable. That is something I reflect on often in my own teaching. But I have learned to draw the line when what becomes memorable is a false premise for future learning. I understand that her goal for the school year is to have her students read and write. What she is doing will probably help her succeed in that. The method she is using is called Evidence Based Literacy Instruction (EBLI). I have no doubt that students being taught by this method leave kindergarten being able to do some reading and writing.

So if a goal as important as reading and writing is met, what’s the harm in her method? Well, let’s think about this. If she is teaching all “irregular” words in this way, she is sending the specific message to her students that many spellings are crazy and cannot be understood. And she is implying this over and over and over. By the end of the year, their overall impression of our spelling system is set. If the first grade teacher is also unequipped to explain words deemed “irregular”, then the students will receive a second year of subliminal messaging that “English spelling is unreliable and can’t be counted on to make sense.” What happens in second grade? More of the same? At what point are the students given the “straight skinny” about their spelling system? At what point do they meet a teacher who is willing to encourage their questions about why words are spelled the way they are and show them how to seek a deep understanding, knowing that what we understand is easier to remember? And if those students are lucky enough to encounter a teacher who can actually explain “irregular” spellings, along with supplying logical and predictable features of our spelling system, how on earth does that teacher have the time in one year to reset the attitude their previous teachers have nurtured? This is not a hypothetical situation. It is what I face every fall with each new fifth grade group.

Like I said before, I believe this kindergarten teacher’s desire to nurture successful readers is sincere. But in a really huge way, isn’t she limiting their understanding to her own? It is obvious that EBLI doesn’t offer any explanations for the spellings of sight words. If it did, this teacher would use them. Her heart is in the right place when it comes to doing right by her students. But how possible is it to be truthful right from the start with beginning readers when the teacher is missing so much herself? I often ponder this very idea because for years I didn’t question the idea of irregular words either. I just accepted that irregular words are words that can’t be explained and need to be memorized. This teacher is making that memorization fun, but in the end it is still just memorization. There is no understanding being offered. And I see a huge difference between “memorize this” and “understand this.”

Now let’s think for a moment about how a word ends up in the disgraceful “irregular” pile. It has to do with the alphabetic principle. We teach students that certain pronunciations will be spelled in certain ways using certain letters. When a word’s spelling deviates from that, it is labeled “irregular.” Some teachers (trying to make learning memorable) even shame the word by calling it “misbehaving.” There are even those who go so far as to put the word in “jail”. I love the fact that teachers are some of the most creative people I have ever met, but I also cringe when they use that creativity to disguise what it is that they themselves do not understand.

Unfortunately, too many teachers do not think young children are capable of understanding much about spelling. Their excuse is that we need to limit their cognitive load. Giving them a reason for a spelling, or planting any seeds about how fascinating and logical our spelling system actually is is out of the question in their minds. In my opinion, when adults decide what a child’s capacity for learning is (without having met the child), that child is instantly disadvantaged. If the only way to teach a child to read and write is to also teach the child that our spelling system is absurd and/or crazy, then I say find another way to teach reading and writing.

The number of classrooms in which children are being taught to read using SWI principles is growing every week. Age appropriate explanations are provided to children in regards to any word’s spelling. Right from the beginning, the children are taught to look for consistent spelling patterns, morphemes, and to recognize word families. They get lots of practice at recognizing grapheme/phoneme correspondences. They are encouraged to notice things and to ask questions. They enjoy making “word family” games for their classmates. And at the end of the school year, they are reading and they are writing. But most importantly, they are moving on to 1st grade expecting to read more, write more, and understand more about our language. No one has to back up the bus and convince them that spelling is in fact logical and fascinating. There is only a moving forward motion in their understanding! Each year they revisit important principles and ask the questions that deepen everyone’s understanding. They pull words out of context, investigate them at whatever level is appropriate, and notice other words that are related morphologically before putting the words back into context and discussing how understanding the word deepens its meaning within that context. Some of the very same things taught or practiced in an SWI classroom are also what is being taught with a method like EBLI. The major difference is the underlying belief that connects each year’s learning.

Imagine I had the choice of sending my young child to one of two classrooms. In both classrooms, there is a strong chance that my child would learn to read and write. The difference in the classrooms is this: In classroom #1, the students will learn that spelling, the system they will use the rest of their lives, is illogical and a lot of the times so crazy you’ll want to roll your eyes at it. They will memorize spellings without much understanding of why the word is spelled that way. They will be taught that some words have explainable spelling patterns and that many do not. They will practice sounding out words, and when a word can’t be sounded out, everyone will laugh at the word. In classroom #2, the students will learn that spelling, the system they will use the rest of their lives, is reliable and logical. They will immediately begin learning that words have structure and how understanding that fact will help them with building related words and spelling those related words. They will learn a “spell it out” strategy in which they identify bases and graphemes within those bases at the same time they are learning the word’s pronunciation and its spelling. They will learn that words have histories and that some words are very old. They will be encouraged to ask questions about what they notice about a word’s spelling. The teacher will help the students think through those questions.

I find it hard to believe people when they imply that it’s not possible to have the students leave kindergarten with the impression that there’s a reason for every spelling.

More and more teachers are proving the opposite of that every day. If you are interested in finding out more about what happens in those SWI kindergarten classrooms, I encourage you to participate in study groups with Rebecca Loveless and Pete Bowers. They have specifically worked with kindergarten teachers and their students.

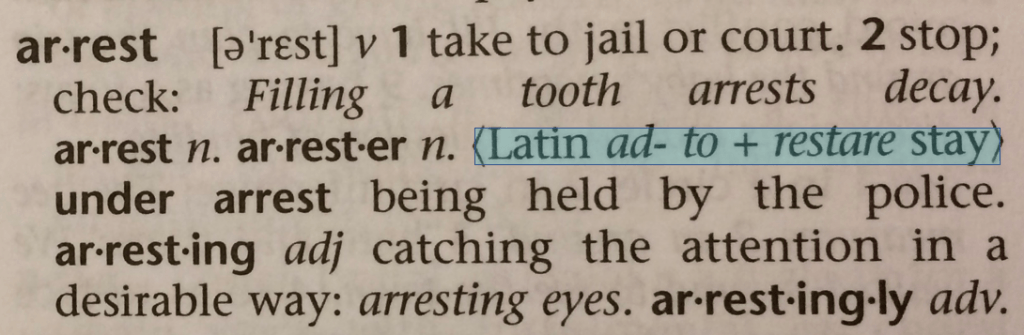

It would be unrealistic to think we can teach without imposing (to some extent) the knowledge limits we each have. But isn’t it our responsibility to constantly reflect on how our own limits affect our students? I don’t like to think that I’ve invited my students into my yard (if we can think of my background knowledge as a yard with fences) and that they become prisoners there. Or that if they ask questions about what is beyond that fence, I would need to make up cutesy explanations to keep them from exploring what I myself am not comfortable exploring. I would rather think of this as me inviting them into my yard, and then when they ask questions about what’s on the other side of the fence, me going with them and modeling how to search for understanding. In the process I would be showing them how to keep expanding their own yard by continually moving those fences. When I am willing to either step outside my “fence” or to keep extending it, we all benefit as learners.

And here’s another thing that doesn’t often get considered. Never forget that students are as deep-down satisfied to prove truths about our English language to themselves as we are! When you spend year after year in classrooms in which the teacher is the expert, and you and your classmates are the buckets to be filled, this kind of investigating can be exhilarating! Students find it refreshing, really, to be given the tools and the opportunity to raise a question and then to prove or disprove it to themselves. My role becomes that of a guide, steering the questions the students have during an investigation back on them as often as possible, but also realizing when they have reached a point where they are truly stuck.

I might also add that I know of several adults with dyslexia who have shared with me their experiences of learning to read in school. They were frustrated much of the time because they were asked to remember bits and pieces without a context. Being told that our language was absurd or crazy made learning to read and write even harder because in effect they were being told it didn’t make sense. Being given a solid understanding of the interrelationship of morphology, etymology, and phonology, however, has turned a truly laborious task into a fascinating one. I’m not saying that their dyslexia has disappeared, but I am saying that they no longer feel as if they are staggering in the dark. Those adults ask lots of questions and think through lots of their own hypotheses thanks to finding Structured Word Inquiry. And every one of them is sharing their understanding with children. They, more than almost anyone else, really get what a difference understanding the spelling system can make.

Doing what is right for children isn’t easy when you are swimming against the educational current. When you have the guidelines of Structured Word Inquiry, when you can see for yourself what is true, and when you can provide evidence to any doubtful package-loving administrators, you do so, and then you just keep swimming. It’s what you do.