I get a lot of great comments about my blog, and about how lucky my students must be to be learning so much about English spelling. I appreciate each and every comment. It’s great that other teachers, parents, tutors, etc. recognize that the understanding I offer is very different to what they themselves learned when they were in fifth grade. Instead of seeing spelling as a mindless exercise in rote memorization, my students see it as fascinating because of all the investigating and discovering they now know how to do. There are stories and explanations embedded in every word, and every word is part of a family, complete with its own family tree!

What isn’t as obvious to my students, but is very obvious to me is how understanding the historical sense and meaning of a word can affect how a person uses that word when writing or understands that word when reading. Since spell check came out, many people are thinking that teaching spelling is not as necessary as it used to be. But then again, they are equating learning spelling with mindless memorization of strings of letters. They have not visited my classroom.

The people who read what I am doing and just know deep inside that this is what should be taught in all classrooms, often accompany their enthusiastic comments with questions.

“I want to begin, but do I know enough?”

“Should I wait until after I take more classes?”

“What other classes do you teach?”

“When did you start?”

“What if the students ask a question, and I don’t know the answer?”

“I’d love to investigate words with my students, but where do I start?”

I get it. When it comes to trying new things in the classroom, it can be a bit overwhelming. Especially when there is no scope and sequence to follow. As teachers, we are used to having step by step teaching guides that set a pace that we can follow. I have always been one to understand that, and yet, I must admit, the professional in me has always felt a bit claustrophobic when using one.

Back when I began teaching 5th grade, I felt confident that I could effectively teach all subjects except two – grammar and spelling. The materials left behind by the previous teacher just felt ineffective. The words, “Get out your English book” could quickly drain the color from the faces in front of me. The students weren’t involved enough in thinking about grammar and thinking about spelling. Everything was “fill in the blank” and “write definitions using the dictionary”. As a student, I used to find that kind of classwork super boring and usually finished the assignment without thinking about what I was doing or why. As a teacher, I couldn’t honestly see any long lasting benefit to the work. I knew I wasn’t really teaching children how the parts of speech they were learning about came together to represent a complete thought. I knew I wasn’t really teaching children to understand English spelling. But how could I teach what I, myself, didn’t understand?

That’s why I was thrilled back in 2004 to have had the opportunity to hear Michael Clay Thompson speak.

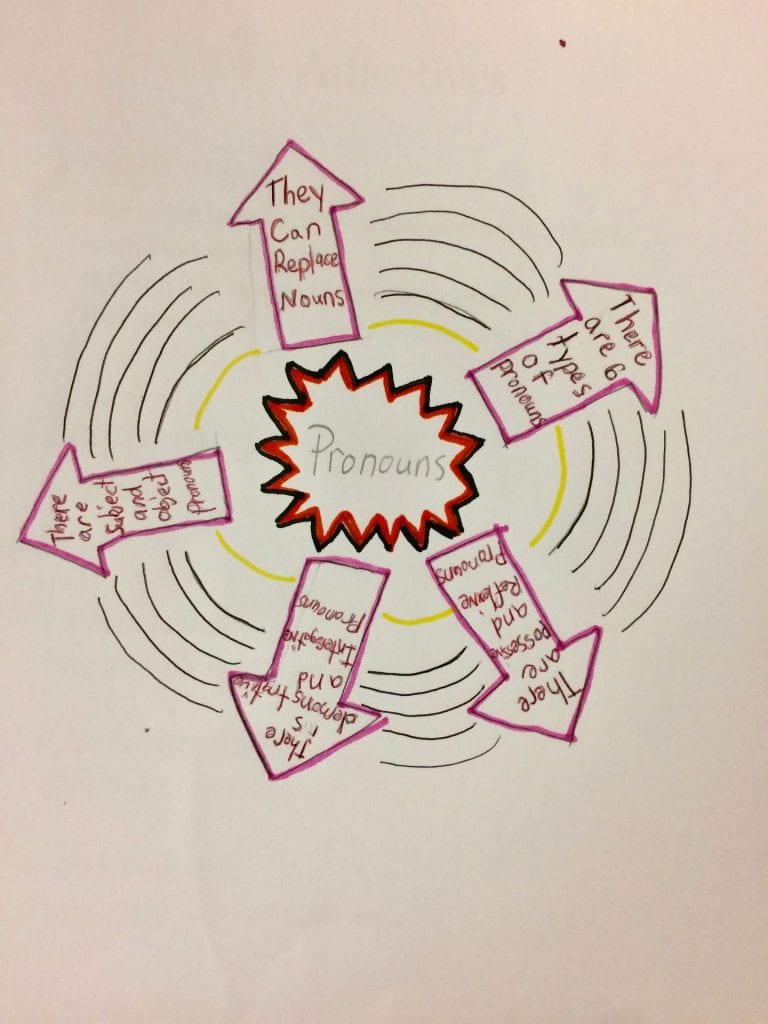

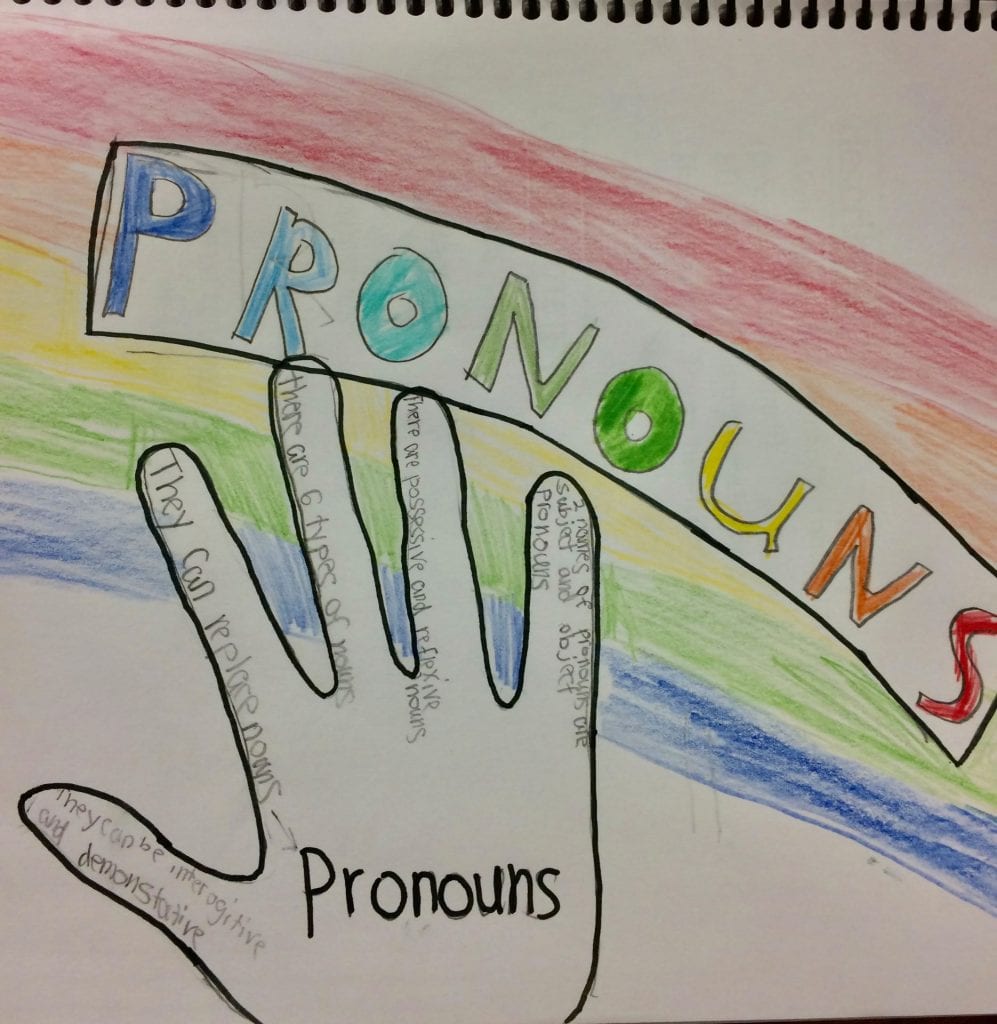

He changed my grammar teaching life! His 4Level Sentence Analysis was intriguing to my students and they learned more about grammar than ever before. MCT made grammar thought provoking, yet understandable. Over the years, my students and I have done a lot of analysis at the board and had rich discussions about the role words can play depending on their placement and function within a sentence. Students don’t just fill in a blank with a good guess. They are able to state how they know that in a specific sentence, a word is a specific part of speech. What follows is that they understand how the meaning of the sentence is constructed. Since 2004, MCT has expanded his selection of age level grammar and writing books. Find a full description and listing of his language arts materials HERE. The following video was taken in February of 2013. I had already been using MCT’s grammar materials for 8 years, but this gives you an example of the kind of thinking required to analyze the structure of a sentence in this way. [You might notice that the word ‘our’ as in ‘our wagon’ was incorrectly identified in this video as a pronoun, and that I did not spot the error. It is the kind of adjective that is a possessive determiner. It is pointing to the noun ‘wagon’.]

Because I was so impressed with the results I was seeing in my classroom, I also began using some of MCT’s other curriculum materials to enhance what I was required to use for spelling. I started with his Building Language books and loved that my students began learning Greek and Latin word stems. I also incorporated vocabulary words from his Caesar’s English 1 book. Teaching some Latin and Greek stems gave my classroom learning experience a big boost! I was satisfied with what I was doing … until I came across Dan Allen’s blog in late 2012.

In 2012 I decided to start a classroom blog, and went in search of other upper elementary classrooms to connect with. When I happened upon Dan’s blog, I was fascinated. He took what I was teaching my students using MCT’s Greek and Latin stems materials to a whole new level. After a weekend spent reading every post on Dan Allen’s blog, I was raring to do what he was doing. I just knew THIS was what I needed to do. THIS was what would make a difference in the lives of my students. Dan was digging into words and letting his students ask really deep, rich questions about spelling. He was teaching his students that spelling is NOT just a random collection of letters, and that it is NOT meant to represent the pronunciation of a word. By Sunday afternoon I had contacted Dan, and he put me in touch with Real Spelling. Seventeen years into my teaching career, I finally began learning and teaching how English spelling works!

I’ve never been shy about trying something new in my classroom. I have always kept my eyes open for ways to make the learning memorable and at the same time for my students to enjoy having learned. Studying English spelling by treating it as a science would be no different. But in such a big way it was. This wasn’t just a new and clever presentation of the same old thing. It wasn’t a program, and it didn’t come in a shiny box with 1001 accessory books/assessments/teacher guides. It didn’t even have a hefty price tag! This was inquiry. This was looking at spelling with a scientific methodology. My students and I could start working the minute we assembled the needed materials: our questions, pen and paper to record our thinking, and dictionaries (regular and etymological). Whoa! I couldn’t think of any good reason not to jump right in!

So here I was, halfway through the school year, knocking on my principal’s door. “Would it be okay if I abandoned our spelling books and tried something different for the second half of this year?” I went on to explain what I understood at that time about Structured Word Inquiry, or as we were also calling it, Scientific Word Investigation. Thankfully, my principal was open to the idea, and I was given permission to see if this way of learning about words could be as powerful in my classroom as it appeared to be in Dan Allen’s.

My next step was to write a letter to the parents of my students to explain what I was doing and why there would no longer be a spelling list or a spelling test. Then, of course, I needed to pitch this idea to my students. Quite surprisingly, not all were in favor of doing away with a spelling test. But as you might guess, those who hated memorizing spelling lists were delighted. And so we jumped in. I reread Dan’s posts and also read Ann Whiting’s blog posts. She was teaching a 7th grade Humanities class in Kuala Lampur and wrote inspiring blog posts. (Ann is no longer teaching, but you can read her wonderful wonderful posts HERE and HERE). I became part of an email group in which questions were shared and discussions ensued. At that point, I mostly listened and learned. I adapted activities from both blogs to use in my classroom. And everyday we spent time investigating and understanding words like we never had before! It was wonderful.

But was I prepared? Was I knowledgeable enough? No. I really wasn’t. But I didn’t pretend I was either. My students knew I didn’t have answers to their questions. I was very clear about that. I told them that I would be learning WITH them. And that was the truth. We asked questions of Real Spelling a lot in those first months. I was also in contact with Ann Whiting and Dan Allen, who were both helpful and made me feel comfortable about asking so many questions. To this day, that group of students holds a very special place in my heart because of the extraordinary shared learning we experienced. Their enthusiasm and level of questioning played off of my own and our classroom became a place where thoughtful questions came to roost. Here are two short videos of those students in the midst of investigations.

By May, my students and I sat down to reflect on the learning. It was unanimously stated that I should continue to study orthography with my next fifth grade group in the fall. I felt the same way. The students felt as if they had learned to spell without really consciously thinking about it. In focusing on the elements in their word sums, and then how to apply suffixing conventions, they had indeed become more accurate in their spelling! Besides spelling, they also felt more of a connection to words. After having investigated and discovered the stories of so many words, the students understood those words in a way that a dictionary definition just couldn’t match . They had zeroed in on the denotations of base elements and the senses that affixes contribute to words. They could compare what they knew a word to be revealing about its meaning to what a dictionary said about the word’s current usage. So many rich discussions!

To reinforce the learning that we were doing, the students brainstormed words that might fit on a matrix for <star>. I printed the matrix out, and scheduled time in each of the three second grade classrooms in our building to teach those students about word sums. In this way, each of my students was paired with a second grade student and then taught them about writing word sums (and also the suffixing convention that deals with doubling). At the time, I had a self-contained classroom (one group of students all day), so each of my students had three opportunities to teach word sums to second grade students. My students found out that, “The best way to know if you know something is to teach it to someone else,” is a true statement!

When school was out for the summer, I needed to seriously consider what training/classes I would seek. The first on my list was a 3 day training on Wolfe Island with Dr. Peter Bowers. Having spent most of my life thinking there wasn’t anything to understand about English spelling, I found this training exhilarating! Pete had spent ten years as a classroom teacher, so I knew he understood a teacher’s perspective. His goal was to open our eyes to what was true about our language and contrast that with what we have been taught that could easily be falsified. He gave us lots of opportunities to dig in and learn in the same way our students would. I met some great people who, like me, were excited to be finally understanding things about English spelling. Many of those friendships have flourished since then, since we email or see each other in classes (through Zoom) once in a while. These days Pete Bowers travels a lot and presents to teachers around the world. If you are wondering whether he’s presenting near you, read more HERE.

In the years since, I have taken classes when I could, started a collection of reference books so I could research on my own, and continued to write blog posts like this one to share some of what happens with my students and some of what I notice on my own. When posting here and when teaching orthography to my students each year, I am always cognizant and appreciative of how my story with Structured Word Inquiry began. It was one teacher sharing and then connecting with another. My regular posts on this blog have been my attempt to pay it forward. I realize that not all who read my blog are classroom teachers, but if you are in any way giving a child truth about English spelling in place of gimmicky tricks that are designed to help a person remember what does not make sense, you are a teacher.

So if you know in your heart that Structured Word Inquiry will help a child in your life, think carefully about how long you intend to withhold that information – that adventure of inquiry. Are you one who is most comfortable waiting for the understanding to gel in your own head before sitting down with a child? Are you one who is most comfortable jumping in and asking questions as you go? You have to determine when you are ready. The child you are thinking of is ready already. Don’t keep them waiting longer than necessary. Luckily there are some introductory classes that will help you learn the terminology to use and some of the basic understanding needed as you begin. Here is a list of introductory course offerings available in the SWI community:

Bringing Structured Word Inquiry into the Classroom – I teach a four episode (90 minutes each) online class. Check this out HERE.

Introductory SWI Class – Lisa Barnett at See the Beauty in Dyslexia offers a three episode (90 minutes each) online class. Check this out HERE.

Intro to SWI – Rebecca Loveless offers an online class. She also offers an ongoing study group opportunity. Check these out HERE.

An Introduction to Structured Word Inquiry – Dyslexia Training Institute offers a six week (30-40 hours) class. Check this out HERE.

I am also adding a link to the joint blog/workshop opportunities (Australia based) of Ann Whiting and Lyn Anderson: Caught in the Spell of Words. Check it out HERE.

The important thing to remember here is that you don’t have to have all the answers as you begin. That being said, you do need to identify what it is you don’t know as you move forward so you can seek the understanding you need. Do not be afraid of making errors. Expect to make errors. Celebrate the day you spot them and replace them with a deeper understanding and new questions. Investigate and present your findings to others. Then have a dialogue about what you found. The most wonderful learning happens when my students present their findings. We all move our chairs so that we are close to the board and the presenters. Then when the presentation is over, the questions, comments, dialogue and learning begins.

I am leaving you with this great quote that has inspired me through moments of self doubt: