Not long ago, a question about the ‘u’ in ‘build came up in a Science of Reading facebook group. It’s the kind of question I like, so I did some research. Etymological sources like Etymonline and Chambers Dictionary of Etymology agree that there isn’t a specific explanation as to why that ‘u’ is there. In the Chambers Dictionary there is a suggestion that perhaps the present spelling is a combination of two earlier versions – bulden and bilden. The Oxford English Dictionary lists one of the Middle English spellings for this word as builde. There is also an indication that by the 1650’s the present spelling was being consistently used. The entry gives a thorough description of how the pronunciation of this word developed. If you have a subscription to the OED, take a look. Even though the combination of information from the three resources makes sense to me, I still refer to this train of thought as a theory or hypothesis. It is not proven. Would I share this information with my students? Absolutely. Would I read part or all of the entries for ‘build’ at Etymonline, Chambers Dictionary, and the OED? Absolutely. But why?

Many teachers will argue that the etymology is too much for their students to handle. They don’t need to know it in order to spell a word. I’ve heard teachers call this kind of information “cognitive overload.” But you know what IS cognitive overload? Being asked to remember a letter string that doesn’t make sense to you – for which this is no connection to anything. Once we can talk about the story of the spelling of ‘build,’ even if what we end up with are theories and hypotheses, it is the beginning of making that spelling memorable.

I’ve been thinking about graphemes a lot recently. Specifically, I’ve been thinking about the graphemes that do not represent pronunciation – like that <u> in build, the <e> in bridge, the <g> in sign, the <l> in could. They are included in a word’s spelling to signal something else. The reason I’ve become thoughtful about these unpronounced graphemes is I’ve noticed a lot inconsistency in the way different sources and teaching materials label and categorize these graphemes. Because there is a variety of descriptions and explanations, educators and tutors aren’t consistent in the way they present information about graphemes to students. I’m wondering if, for the sake of teaching children what is consistent about English spelling, we might come together to explore this topic and consider the facts.

What is a grapheme, anyway?

Let’s begin with a definition of ‘grapheme.’ Several linguistic sources define a grapheme as “the smallest meaningful contrastive unit in a writing system” or “the smallest functional unit of a writing system.” As I continued to look for how other people define a grapheme, I found the following, written by various groups that specifically support teachers.

“A grapheme is a written symbol that represents a sound (phoneme).”

“Graphemes give us the visual component of a sound.”

“The individual letters or groups of letters that represent the individual speech sounds are called graphemes.”

Notice how one group (linguists) does not specifically define a grapheme as representing sound (at least not as part of its definition) and groups serving teachers do. I found this quite interesting. I wondered what Richard Venezky had to say in his book The American Way of Spelling.

“To map spelling into sound, graphemic words must be segmented into their basic graphemic units. This requires schemes for handling letters like the final <e> in rove and the <b> in debt. Is the <e> in rove connected to <o>, forming the discontinuous unit <o…e>, or is it part of the unit <ve>, or is it a unit by itself? Similarly, how is the <b> in debt to be handled — as part of the unit <eb>, or as part of <bt>, or as a separate unit? Are the silent <e> in rove and the silent <b> in debt equivalent? The solutions to these problems should be not only consistent with the way similar letters are handled, but also general enough to handle new cases that may arise. They cannot be settled satisfactorily by simply labeling all unpronounced letters as silent. Consider the so-called “silent” <b>’s in subtle and bomb. We could say that the <b>’s in these two words are silent, and let the matter rest. But by doing so, we would lose an important difference between these two cases. The form subtle occurs only with the <b> corresponding to zero, but <b> in bombard and bombardier corresponds to /b/. It is not sufficient, therefore, to say that the second <b> in bomb is silent; more exactly, it is silent before word junctures and before certain suffixes (compare bombing, bombs, bombed), and otherwise pronounced /b/. This is one of the forms of orthographic patterning that almost all traditional treatments of spelling overlook. ”

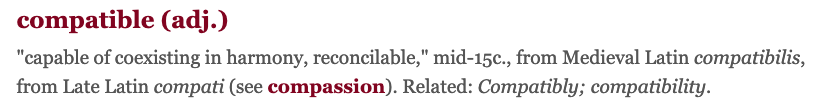

There’s a lot there to consider, isn’t there? Let’s begin with what he said about the <e> in ‘rove.’ “Is the <e> in rove connected to <o>, forming the discontinuous unit <o…e>, or is it part of the unit <ve>, or is it a unit by itself?” When people refer to the discontinuous unit <o…e> or the unit <ve>, they are referring to how that <e> is functioning in the word, aren’t they? We know which phoneme is being represented by the grapheme <o> because of the <e>, right? Without that <e>, the <o> would represent a different phoneme. The unit <ve> reminds us that no complete English word ends with a <v>. Notice the language that Venezky uses to describes these two functions of <e> in this word (rove). He does not call the discontinuous unit <o…e> a split digraph. He does not call the unit <ve> a digraph. But so many of the teaching resources and programs out there do.

If the <ve> in ‘rove’ is a digraph, then by definition those two letters must be representing the phoneme /v/. If the <o…e> is a digraph, then those two letters must be representing the phoneme /oʊ/. Is that the case? Is a <ve> digraph functioning the same as a <th>, <sh>, <ch>, <ea> or <ee> digraph?

What if, instead of teaching children that <o…e>, <e…e>, <a…e>, <i…e>, and <u…e> are split digraphs, we taught them that the single, final, non-syllabic <e> in ‘rove’ is a grapheme that is not representing pronunciation. It functions differently. In the word ‘rove’ it signals the pronunciation of another letter. It signals that the <o> will have a long pronunciation /oʊ/. Taking it a step further, what if, instead of teaching that <ve> is a digraph, we taught students that the single, final, non-syllabic <e> is not representing pronunciation. It functions differently. In the word ‘rove’, besides signaling the long pronunciation of the <o>, it is also preventing this word from ending in a <v>.

The consistent part in both of those scenarios is that the grapheme <e> is single, final, and non-syllabic. It is NOT there to represent pronunciation. It MUST be there for another reason. Using the word ‘rove,’ we were able to illustrate two of the possible ways that final <e> can function. Wouldn’t it be fun for your students to discover more? Maybe you could set up an investigation in which you list the words bike, house, give, blue, bathe, dance, and large. Ask the students to consider the word with and without the <e> before they hypothesize its function!

What about other letters that are often referred to as ‘silent’?

I take you back to the excerpt from Venezky.

“…how is the <b> in debt to be handled — as part of the unit <eb>, or as part of <bt>, or as a separate unit? Are the silent <e> in rove and the silent <b> in debt equivalent?”

So back to the question that was asked in the Science of Reading group. I responded by sharing a blog post in which I had previously investigated ‘build’ (along with 31 other words that supposedly had “silent letters”). It is called “Guess What? They’re ALL Silent Letters!” A few people in the thread linked Etymonline in their comment and suggested there would be an answer there although they didn’t identify what that answer would be. Beyond that, the comments from others highlighted just how inconsistent the understanding is when looking at unpronounced graphemes in words like ‘build.’ Read some of those comments.

“The <bu> grapheme appears in 3 words representing the /b/ sound: build, buoy and buy!”

“The words “buy” and “buoy” also have a “u” that just seems to be there to support the “b”.

“Bu makes the /b/ sound.”

The first commenter considers <bu> to be a digraph, meaning it is the combination of ‘b’ and ‘u’ that create the phoneme /b/. But when I announce those three words, one stands out as different from the others – ‘buoy.’ The ‘u’ is not joining with the ‘b’ here. It is representing its own pronunciation. Compare ‘buoy’ to ‘boy.’ I think you will agree that the ‘u’ in ‘buoy’ has a different function that the ‘u’ in ‘buy’ or ‘build.’ It represents pronunciation where the ‘u’ in the other two words does not. The site ToPhonetics represents ‘boy’ as /’bɔɪ/ in both American and British pronunciations and ‘buoy’ as /ˈbui/. Even if you are not familiar with IPA, you can see that these two words have different IPA symbols, meaning they have different pronunciations. And if <bu> is a digraph, wouldn’t it be consistently a digraph? There are many words in which /b/ is simply represented by <b>.

The second commenter doesn’t call the ‘bu’ a digraph. This person, instead, says that ‘u’ supports the ‘b’ in ‘buy’ and ‘buoy.’ What is meant by “supports the ‘b’?” Not sure. But what I am sure of is that both of these commenters realize that the ‘u’ is not representing pronunciation on its own. They are just not sure how to identify what it is doing instead. Why is it there? Here’s another comment.

“In “guild” and “guy,” it makes sense. The u blocks the i and y so they can’t make g say /j/. Not sure if that carries over to “build” and “buy,” but I would love to know!”

This commenter has an understanding that when we see a ‘g’ followed by a ‘u’, the ‘g’ is /g/ in that word. Think of guard, gum, gulf, guess, guest, gust, gush, and lots of others. If, like the commenter says, the “u blocks the i and y so they can’t make g say /j/,” then what’s happening in gum, gulf, gust, and gush? The ‘u’ in those words is representing the /ʌ/ phoneme and is not blocking any vowels. I’m not saying the ‘gu’ letter string doesn’t usually signal that the ‘g’ is pronounced as /g/. I’m saying it probably doesn’t have anything to do with blocking a vowel. Perhaps we can think of this situation like this. When we see a <g> followed by <u>, we know to pronounce the <g> as /g/. That holds true whether the <u> is representing a vowel phoneme in the word or whether its not representing pronunciation at all.

More comments…

“I don’t have an official answer to this but if you took out that u and it was bild I’d pronounce that similarly to wild and mild. But guild and build rhyme so the u must help break that -ild ending pattern…?”

“Perhaps it keeps the i short so it isn’t a “wild” “child” word.”

Both of these comments focus on a comparison to wild, mild, and child. Interesting.

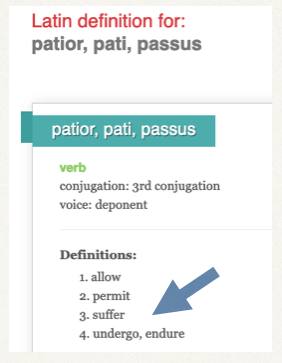

Maybe it would be best to redefine a grapheme as “the smallest functioning part of the writing system that may or may not represent pronunciation.” Let’s take another look at the words of Richard Venezky.

“The solutions to these problems should be not only consistent with the way similar letters are handled, but also general enough to handle new cases that may arise. They cannot be settled satisfactorily by simply labeling all unpronounced letters as silent. Consider the so-called “silent” <b>’s in subtle and bomb. We could say that the <b>’s in these two words are silent, and let the matter rest. But by doing so, we would lose an important difference between these two cases. The form subtle occurs only with the <b> corresponding to zero, but <b> in bombard and bombardier corresponds to /b/. It is not sufficient, therefore, to say that the second <b> in bomb is silent; more exactly, it is silent before word junctures and before certain suffixes (compare bombing, bombs, bombed), and otherwise pronounced /b/. This is one of the forms of orthographic patterning that almost all traditional treatments of spelling overlook. ”

For teachers who don’t know the particular reason that a grapheme isn’t representing a phoneme, it seems easy to lump it in with all of the other graphemes that also don’t represent a phoneme and call it a silent letter. But how enlightening is that for any of us. Venezky illustrates with the example of ‘bomb’ and ‘debt’. They each have an unpronounced <b>. But as he goes on to say, they are unpronounced for different reasons. Understanding those reasons can mean the difference between remembering the spelling of those words and going back to the default spelling method most children have which is “sound it out.” In this case, “sound it out” will only lead to misspelled words.

Moving forward.

If you can get a copy of Venezky’s book The American Way of Spelling, I recommend it. I refer to it often and reread sections when I need to. It has been so helpful in developing my understanding of words and their spellings.

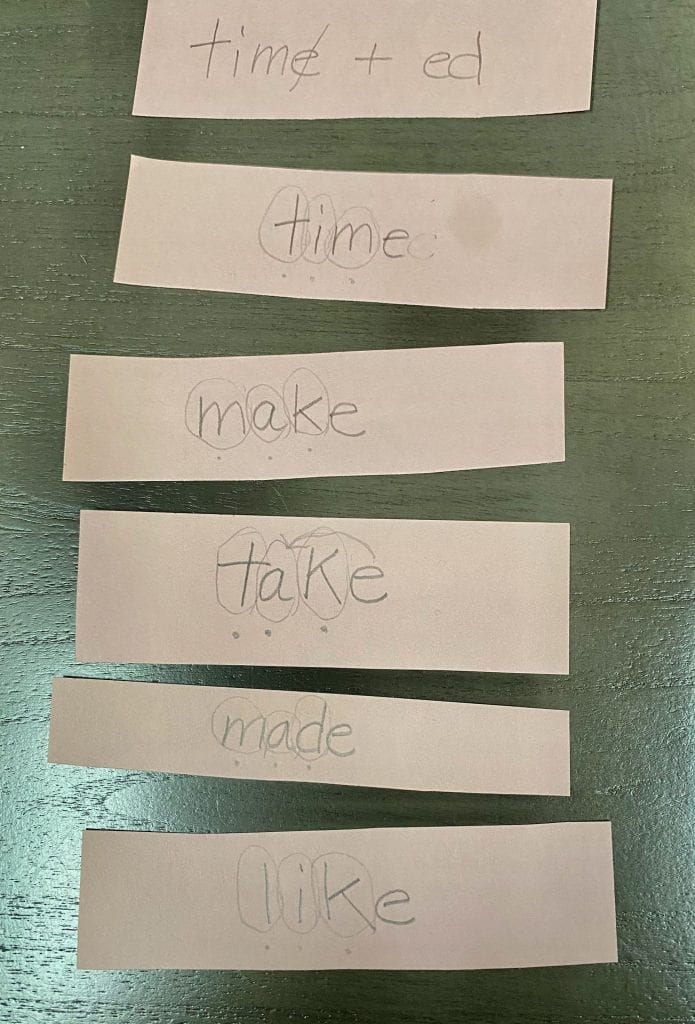

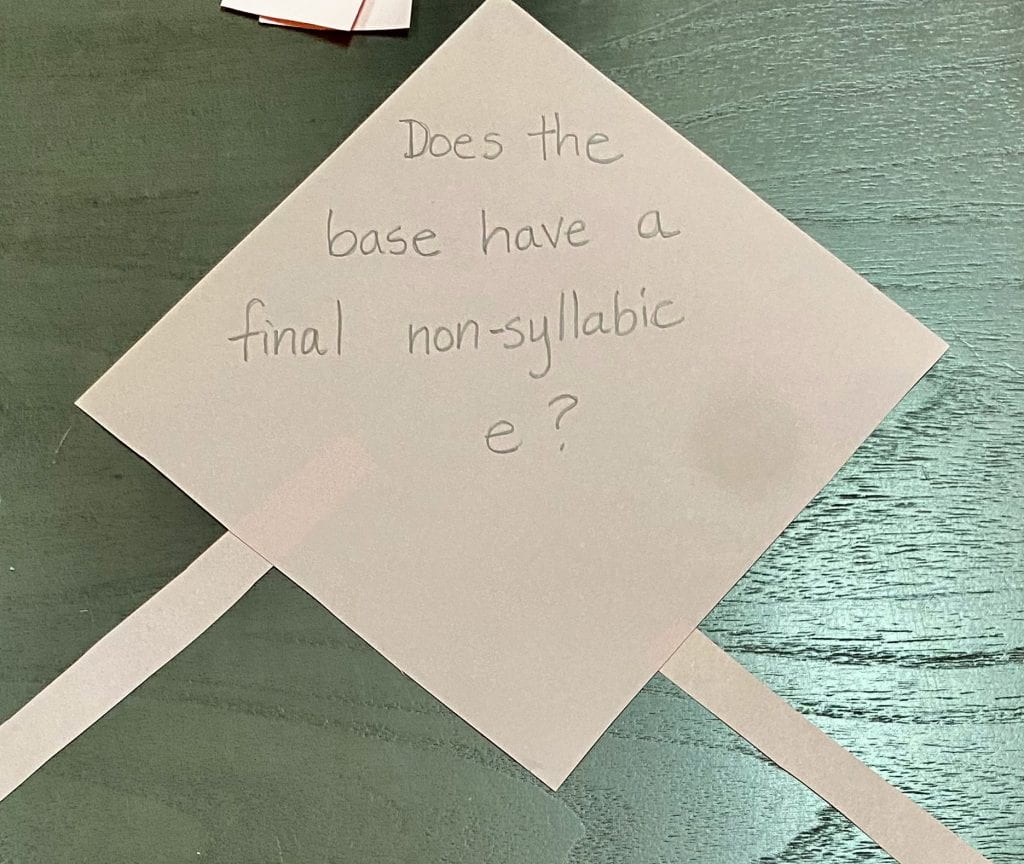

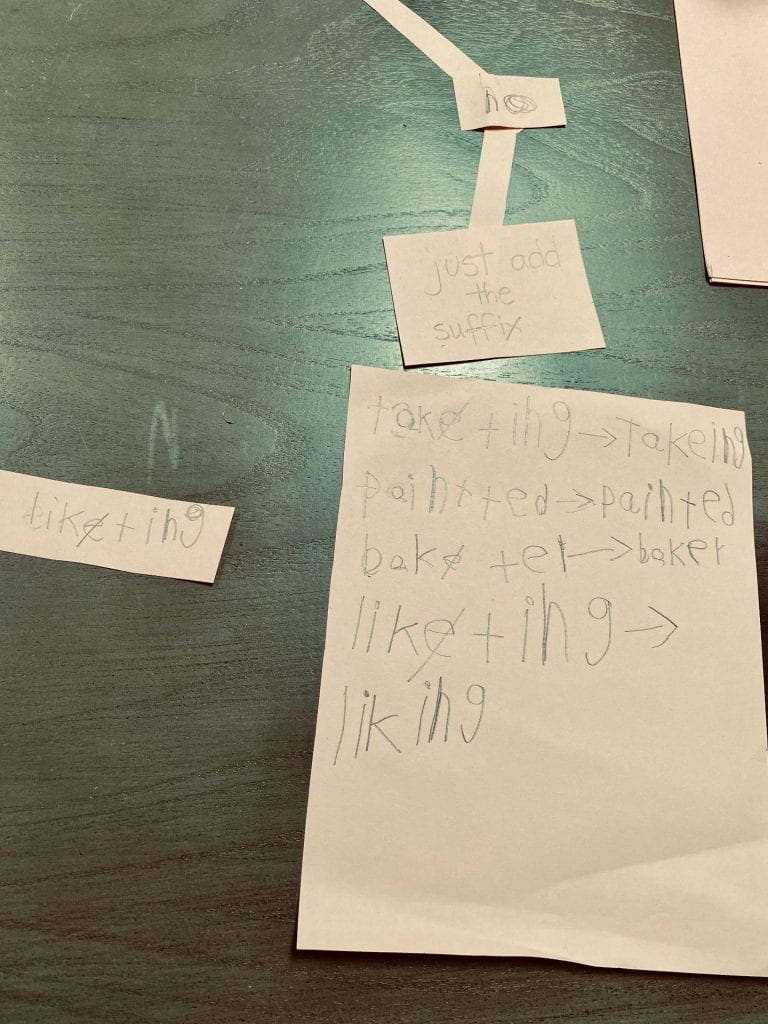

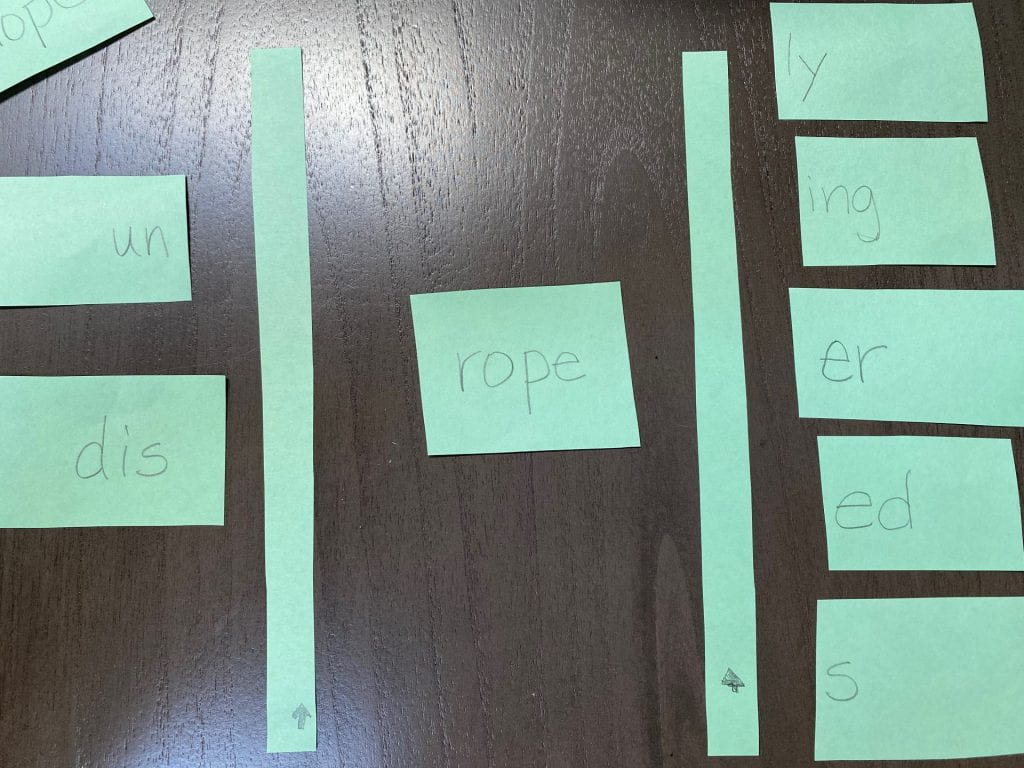

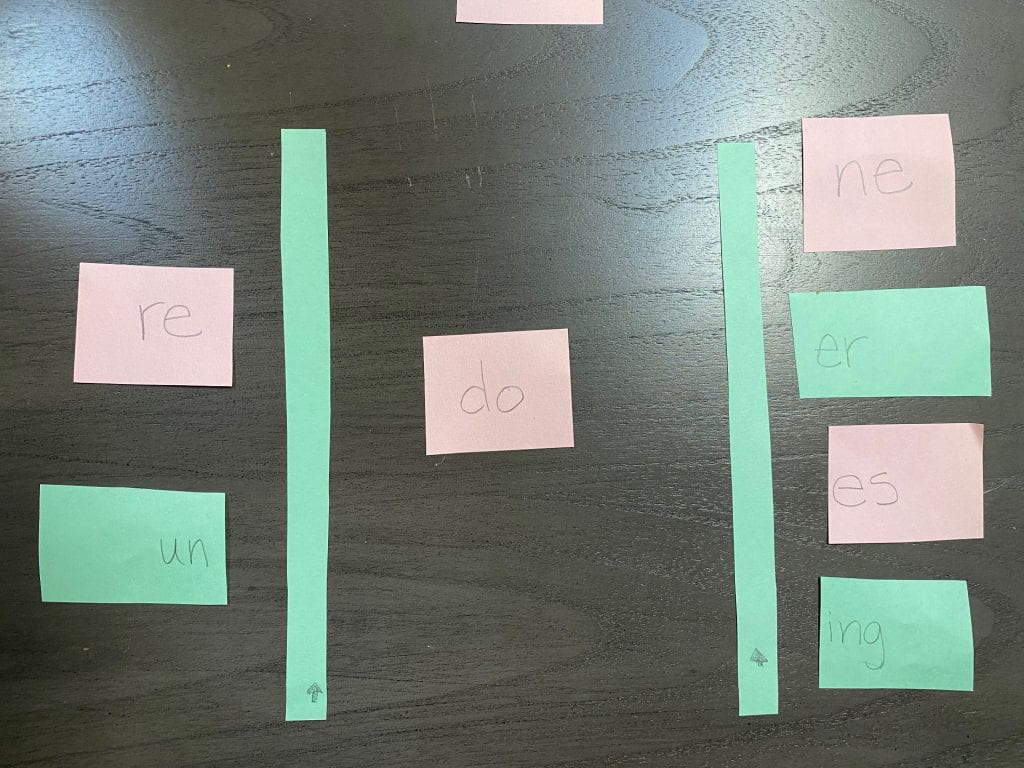

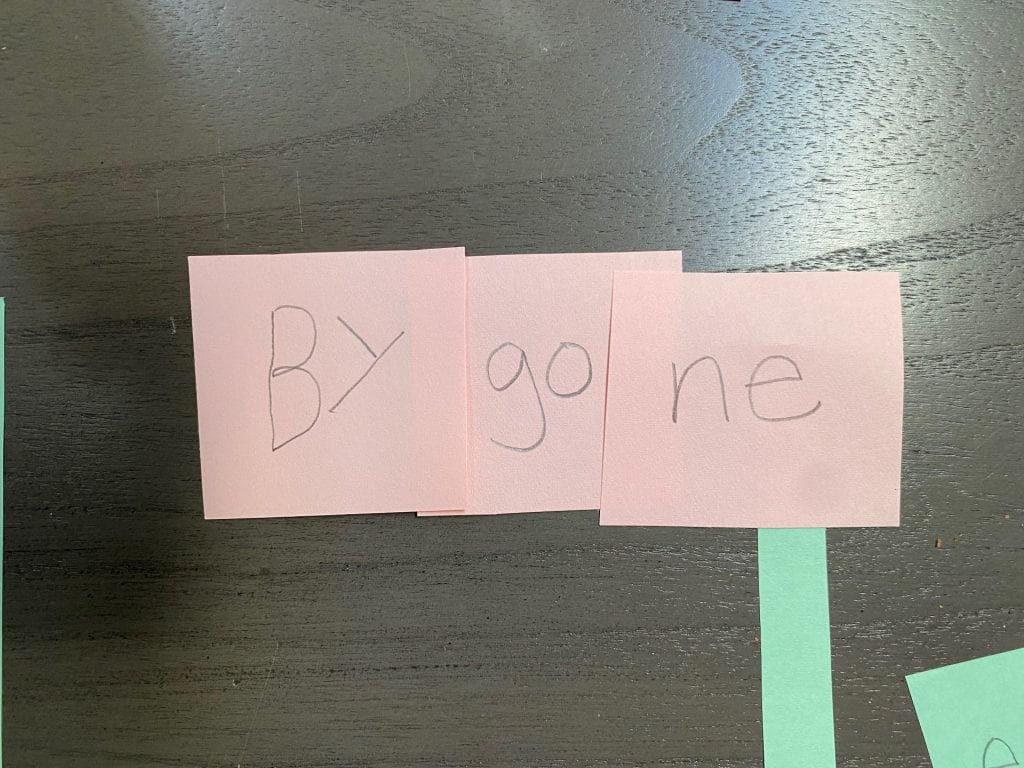

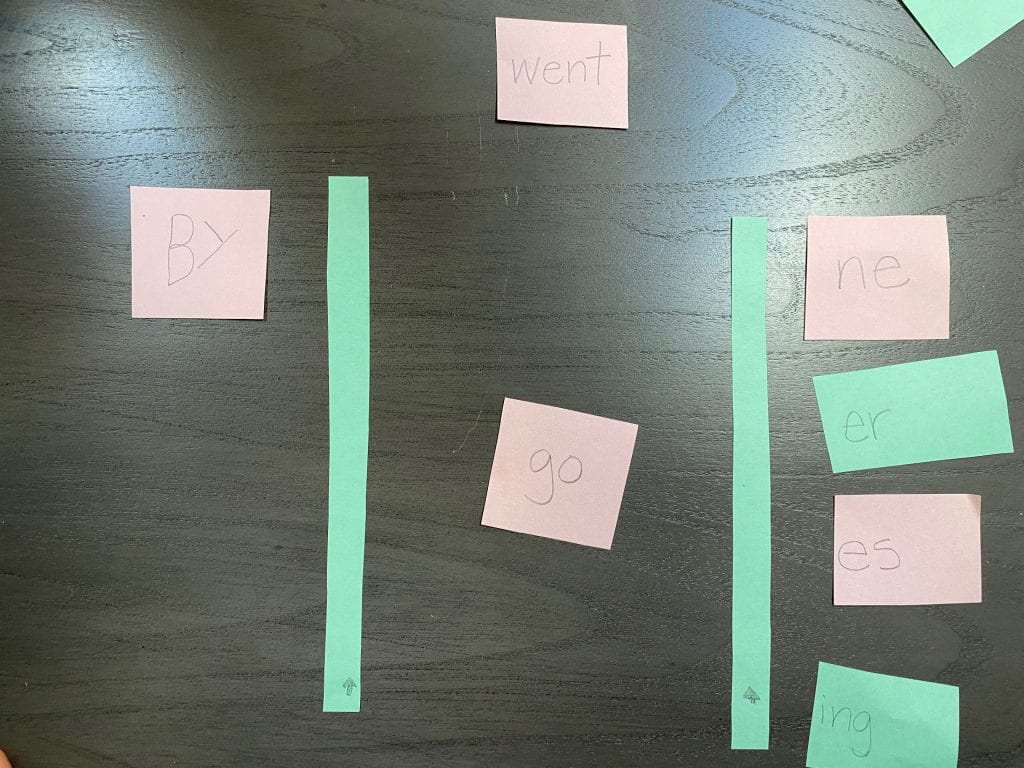

Some of these unpronounced graphemes make for pretty cool investigations though. Think about the reasons for the single, final, non-syllabic <e>. Collect a group of words with final unpronounced <e>’s as I mentioned earlier. Have your students group them according to the function of that final <e>. Maybe it will require collecting more words. Maybe it will require considering the word without the <e> and if that would affect the word’s pronunciation. Here’s a video my students made after doing such an investigation. The video mentions six different reasons for that <e> but there are more!

As you notice one of these unpronounced graphemes in a word, see what else you can find out. Resist the urge to pair it with the letter before or after it and labeling it a digraph without a solid reason. As an example, I looked at Etymonline to see what information I could find about the <l> in ‘talk’. I have heard it is related to ‘tale’ and that is the reason for the ‘l’, but I wanted to see if there was more to know.

From what I read here, the <l> has always been part of this word’s spelling. I don’t see any earlier versions of the spelling without the<l>. As I have heard before, it is “ultimately from the same source as tale.” To talk is how we share a tale! What comes next in this entry is gold! Check out the relationship between tale-talk, hear-hark, steal-stalk, and smile-smirk! The second spelling formed with the “rare English formative -k.” I wondered if I would find the same information in the OED (Oxford English Dictionary). In that reference I learned that “it is notable that talk v. and stalk v.1 show a strong formal similarity to walk v. beyond simply the ‑k‑ element, and it is possible that analogy with walk v. has prompted the introduction of this element in either or both of these verbs. How about that! So perhaps ‘talk’ was the reason for using the “rare English formative -k” in the spelling of ‘talk’ and ‘stalk’. Now we have a story about ‘talk’ that not only connects it to tale but also to walk, stalk, hear/hark, smile/smirk.

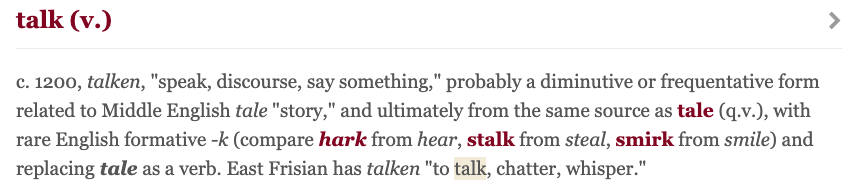

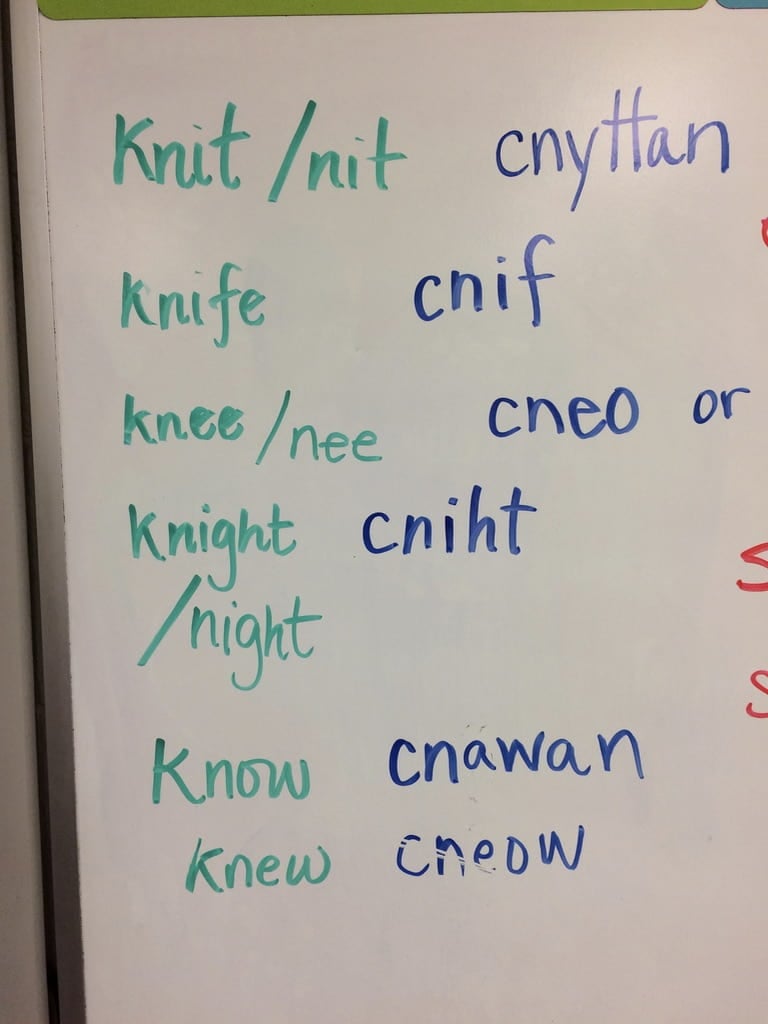

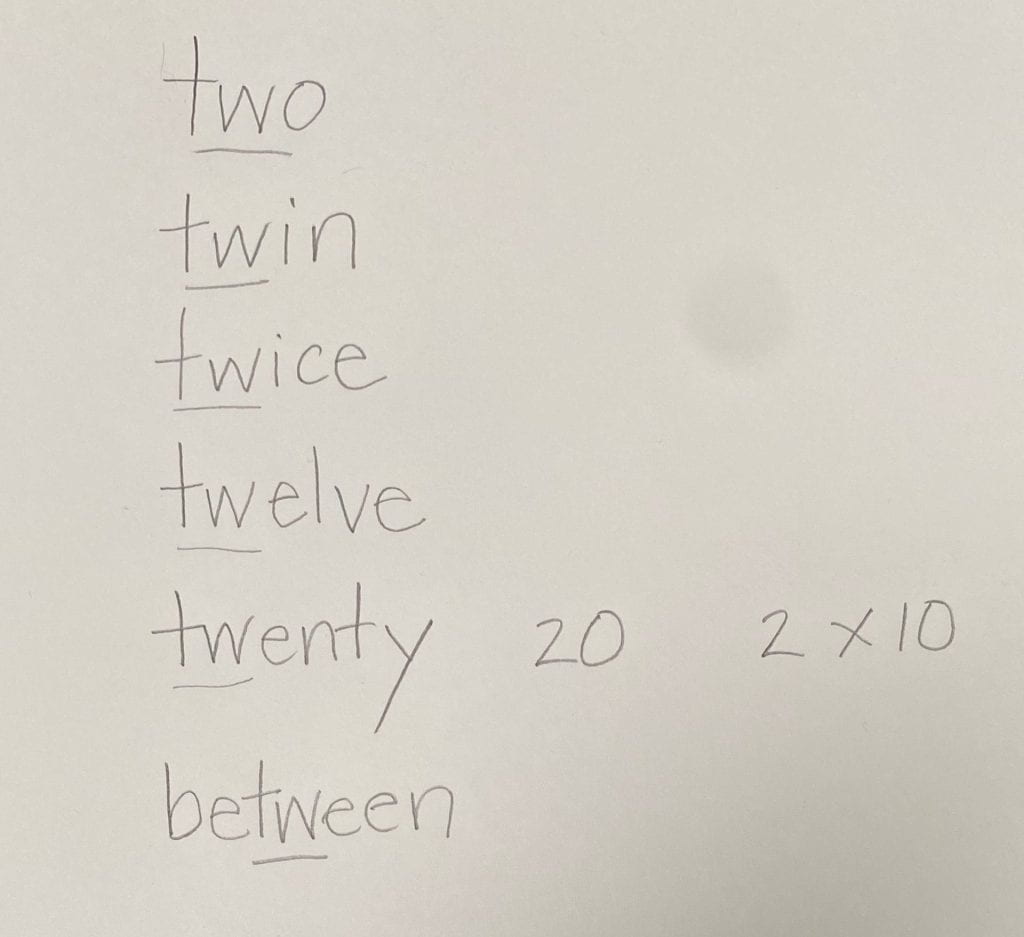

My classroom became known for our word investigations. One time another classroom asked us about the word ‘know’ and why it was spelled with a <k>. After thanking them for such a great question, I had my students collect a list of words (using Word Searcher) that started with the spelling <kn>. Once we wrote our list on the board, I asked students to each choose one of the words and to look at it at Etymonline. They were to find out what the language of origin was and how it was spelled in that language. (I knew ahead of time that the words would be from Old English and that the information would be up front in the entry.) Next the students wrote the original spelling next to the word on the board. It didn’t take long before we realized that in Old English these words were spelled with <cn> and not <kn>. We found out later that at that time the <cn> was pronounced as /kn/.

Here’s the entry for <kn> at Etymonline.

Now we understood that in Old and Middle English, both the <c> and <n> were fully voiced. It was between 1650 and 1750 that the /k/ weakened and faded in the pronunciation of this word. Today we only pronounce the <n>. The <kn> has stayed part of the spelling to remind us of this word’s history. Once my students understood the story they were ready to visit the classroom where the question originated and share their understanding!

There are many of these unpronounced graphemes and they reside in words for different reasons. I encourage you to explore with your students. Find out what purpose that grapheme serves and acknowledge that not all graphemes represent phonemes! I would love to hear where your investigations take you!