Ever have a student finish an assignment before everyone else and ask, “What should I do now?” Recently I asked everyone to write an editorial. We all started at the same point, but once the writing started, everyone was in their own lane and working at their own pace. When the first few were done, they asked that question. “What should we do now?” I gave them things to investigate. Some finished their first investigation and asked for a second. All the while, other students were still working on their writing. And it was all good. No one felt rushed in their task.

We have moved on from editorial writing, but in the meantime, I assigned three more projects. One involved partner work in which students investigated Latin verbs. They removed Latin suffixes to see whether their particular Latin verb became a modern English unitary base or a set of twin bases. (They will be featured in a future blog post.) Then a poem was assigned in which the students were to use the digits of Pi to determine how many words would be on each line. (They will be featured in a future blog post.) The third project involved creating a pseudosaur. Inspired by the work of Skot Caldwell’s Grade 5 students (use this link) in Canada, we wanted to create our own. Most of the students are still working on those. But that also means that plenty of students have finished all major projects and continue to ask for things to work on. I’m loving it. Students are investigating all sorts of things!

The unplanned investigations have been of benefit to all of us because the investigator presents his or her findings with the class. This gives us the opportunity to talk about lots and lots of things we might not have talked about otherwise. I am thrilled. Here are some examples of the types of investigations going on:

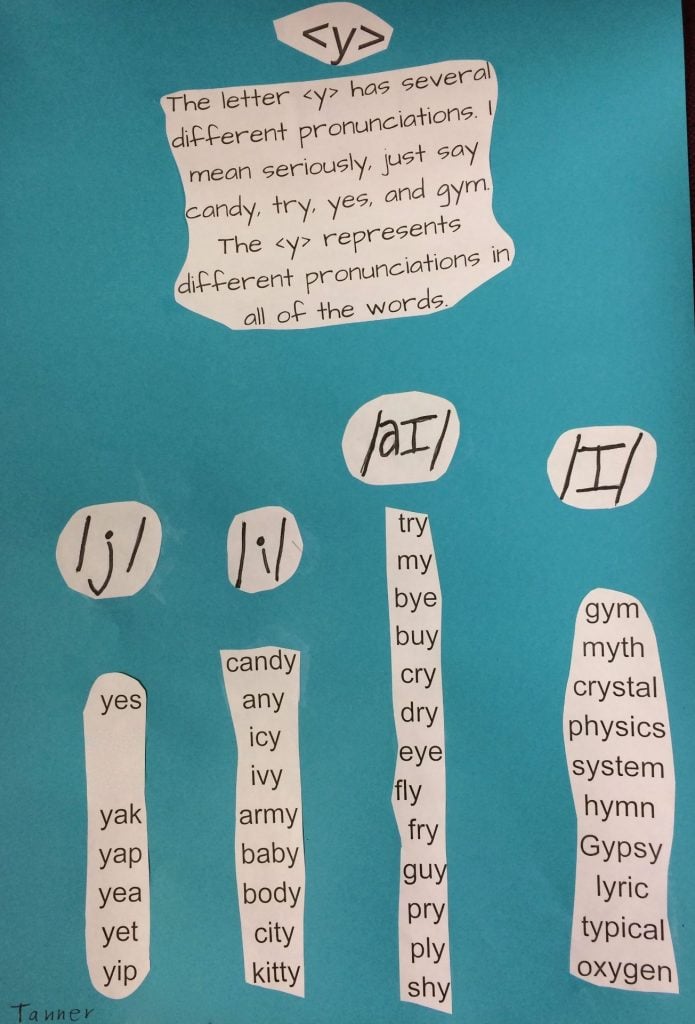

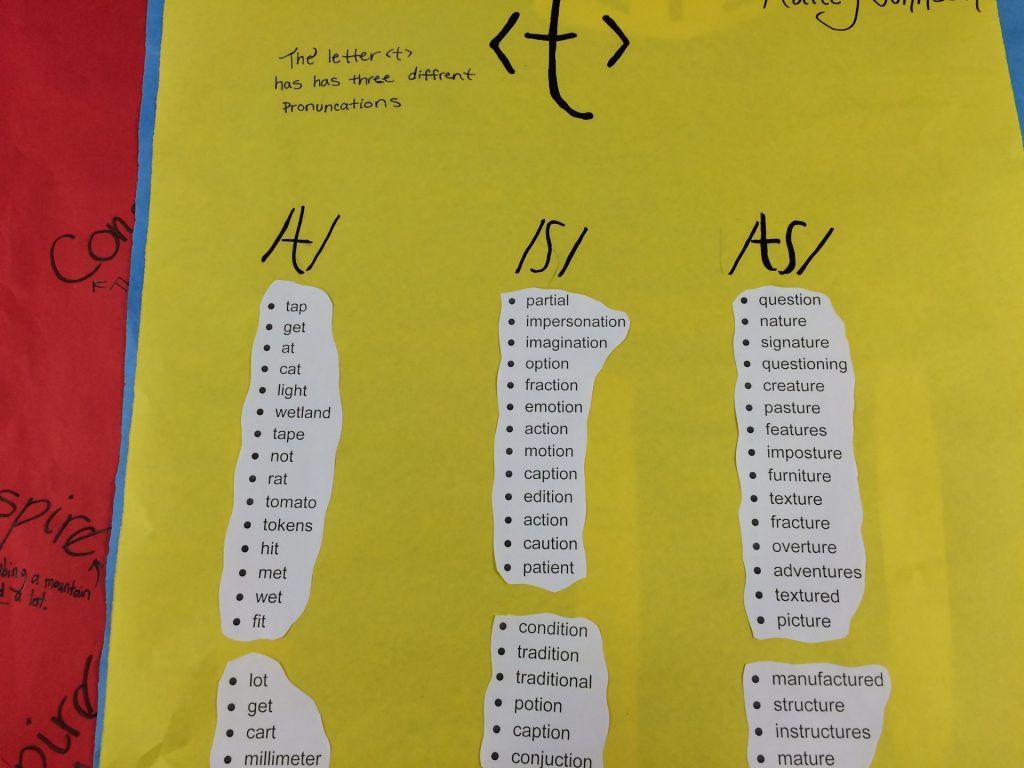

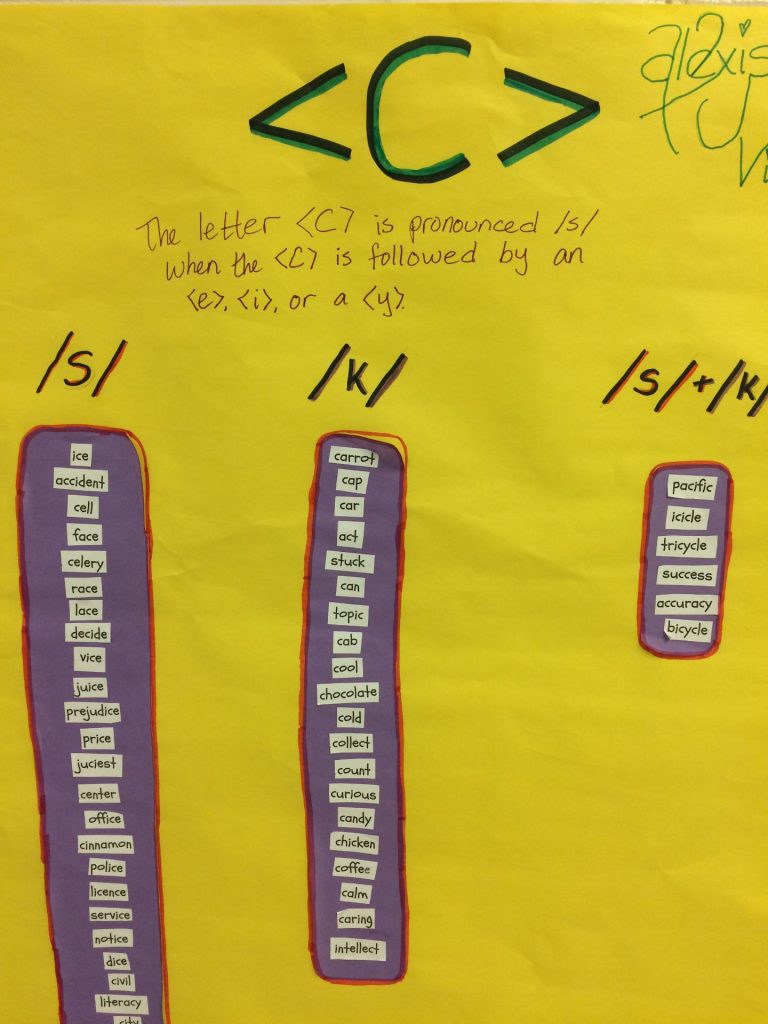

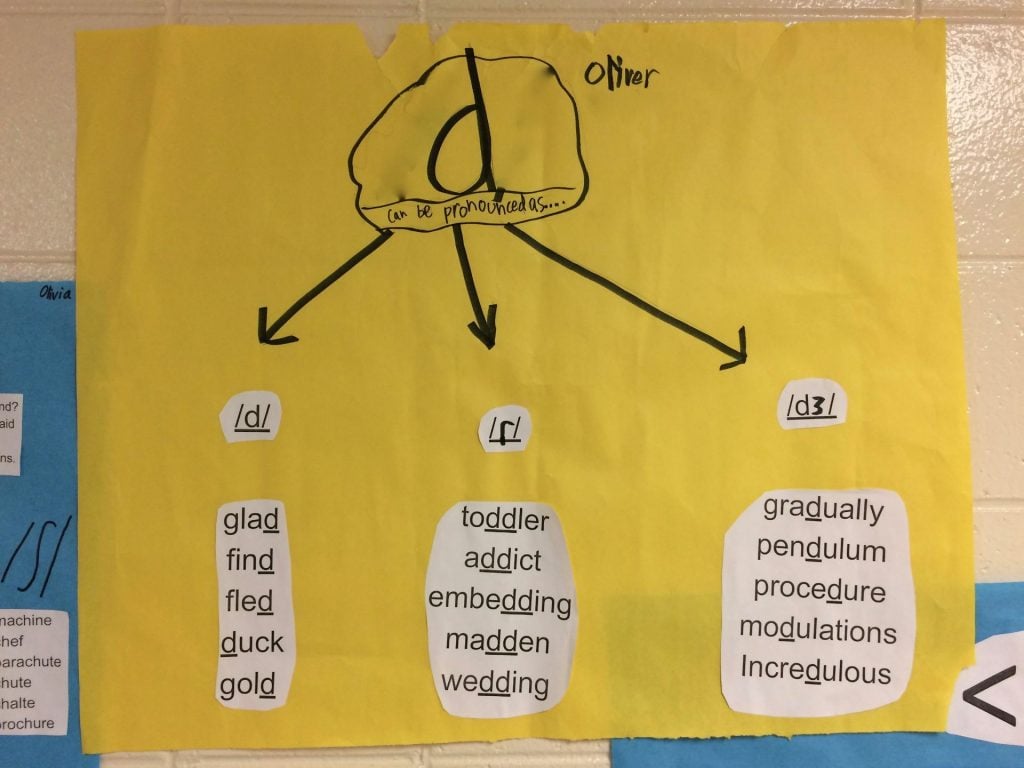

Looking at specific letters and noticing that that letter can represent several pronunciations, depending on the word it’s in.

This type of investigation gave us the opportunity to talk about the investigated letter being initial, medial, or final in the word. We also had the opportunity to begin learning about IPA (the International Phonetic Alphabet). The IPA is a standardized representation of the sounds of spoken language. In looking at each of these symbols, we have paused to feel where in our mouths we vocalize these letter representations. In doing so we have better understood the symbols. For example, when pronouncing the <t> in <tap>, we felt our tongue tips touch the ridge right behind our teeth just before air pushed it off. When pronouncing the <t> in <partial>, we noticed that our tongues came close to that ridge, but never actually touched it. When we pronounced the <t> in <question>, our tongues once again touched the ridge, but in a different way than with <tap>. It was more the sides of our tongues. What we heard reminded us of the pronunciation of <ch>.

One other interesting thing that was observed is that when the <t> is represented with a /tʃ/ pronunciation as it is in question, the <t> is usually followed by either an <ion> suffix or an <ure> suffix. We compared that to the suffixes on the words in which the <t> is represented with a /ʃ/ as it is in imagination. Most of the words on this list had an <ion> suffix. That raised the question of why the <t> is pronounced as /tʃ/ in question, but /ʃ/ in imagination? The thought was that there was an <s> in front of the <t> in question, and that wasn’t the case in any of the words in which the <t> was pronounced as /ʃ/. So our hypothesis was that the <s> affected the pronunciation of the <t> in the word question. It was agreed that we needed to gather more evidence.

The look at <c> was interesting too. After Alexis finished collecting words in which the <c> was pronounced /s/ and in which the <c> was pronounced /k/, I asked her to look at the letters following the <c>. She came back and reported that when the <c> was pronounced /s/, it was followed by either an <e>, <i>, or <y>. If the <c> was pronounced /k/, it was followed by either an <a>, <o>, <u> or a consonant. We practiced reading the words out loud and took turns explaining the phonology of the <c> in each word. Then we looked at words with two <c>’s, explaining the pronunciation of each one. In the end, one student suggested we create an activity to take to the second grade classroom so they could learn this too!

Another letter we looked at was <d>. I asked Oliver to investigate three pronunciations of <d>. He collected words in which the <d> was pronounced /d/, in which it was pronounced as /ɾ/, and in which it was pronounced /dʒ/. When sharing this with the class, we all talked about the way we pronounce <d> as /ɾ/. Even though we see two <d>’s, we hardly pronounce a clear /d/ at all. With a word like <glad>, we feel our tongue touch the ridge behind our teeth. With a word like <wedding>, our tongue barely touches the ridge! We quickly pronounce the two <d>’s as barely one! When Oliver read off the list of words in which the <d> is pronounced /dʒ/, we talked about why these words might sometimes be misspelled. Someone pointed out that in every word, the <d> was followed by a <u>. We wondered if that is always the case ( we realized this was a very short list and wasn’t a big enough collection from which to draw conclusions).

Looking at specific digraphs and noticing that that digraph can represent several pronunciations, depending on the word it’s in.

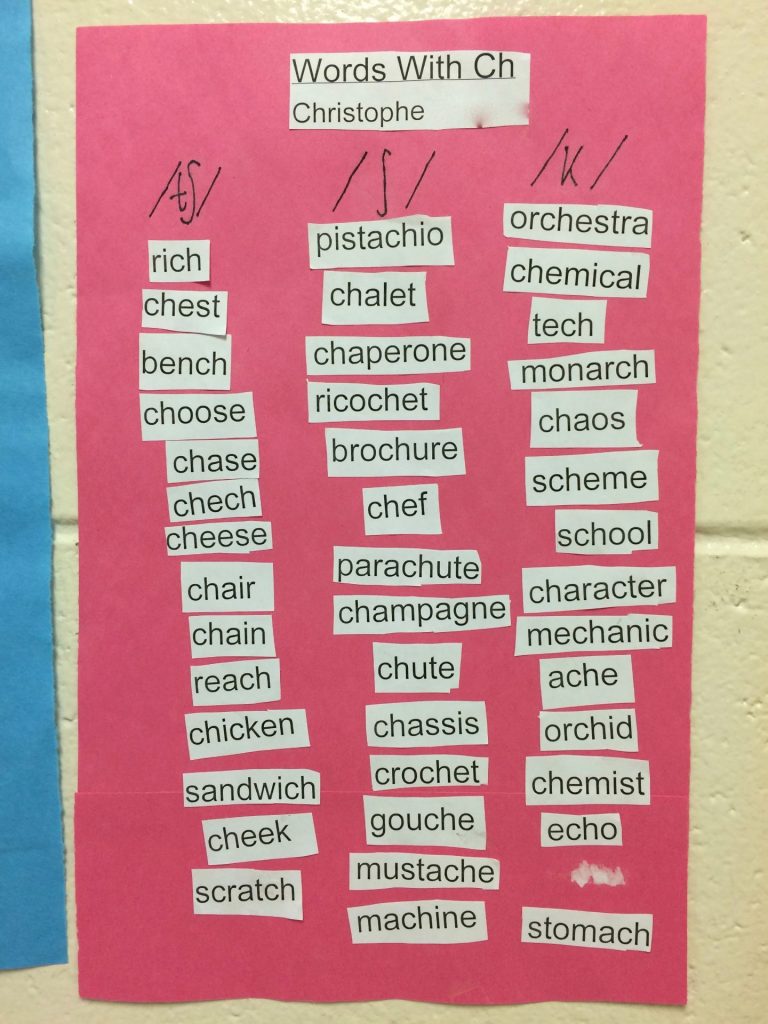

In looking at the <ch> digraph, we recognized the IPA symbols /tʃ/ and /ʃ/ again. We were now becoming familiar with the pronunciation represented by those IPA symbols. We practiced feeling where those pronunciations were made in our mouths again. We noticed that when the <ch> is represented by /tʃ/, the <ch> can be initial or final in the word. We recognized that many of the words in which the <ch> is represented by /k/ are from Greek. We agreed that we couldn’t assume all of them were since we hadn’t looked them up. (I put “checking out the origin of these <ch> word with a pronunciation of /k/” on the list of possible future investigations for some curious student.) When we read the list of words in which the <ch> is represented by the pronunciation /ʃ/, I asked if anyone knew if many of these originated in a specific language. They guessed it was Spanish, so I added this list of words to my “list of possible investigations for some curious student” as well. It will be interesting to find out the language origin of these words. When the presenter hesitated to pronounce <chalet>, but did not hesitate with <crochet> and <ricochet>, I asked him what all three had in common. I pointed out that they were from the same language and would be pronounced the same. He pronounced it, but was totally unfamiliar with the word, so we talked about what it meant.

Comparing <ge> to <dge>, <ch> to <tch>, and <k> to <ck>. If they represent the same pronunciation, when is each used?

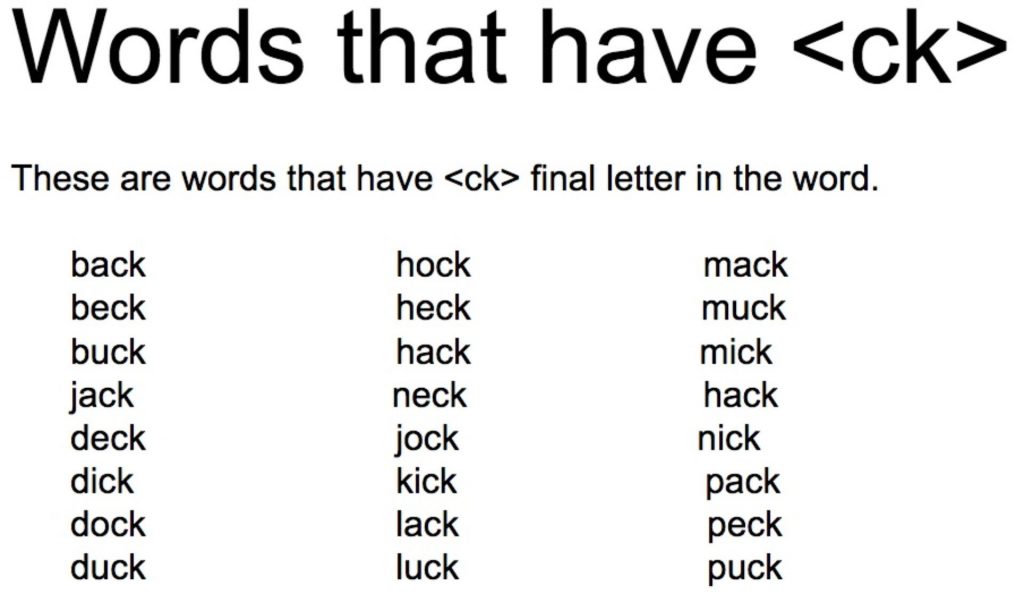

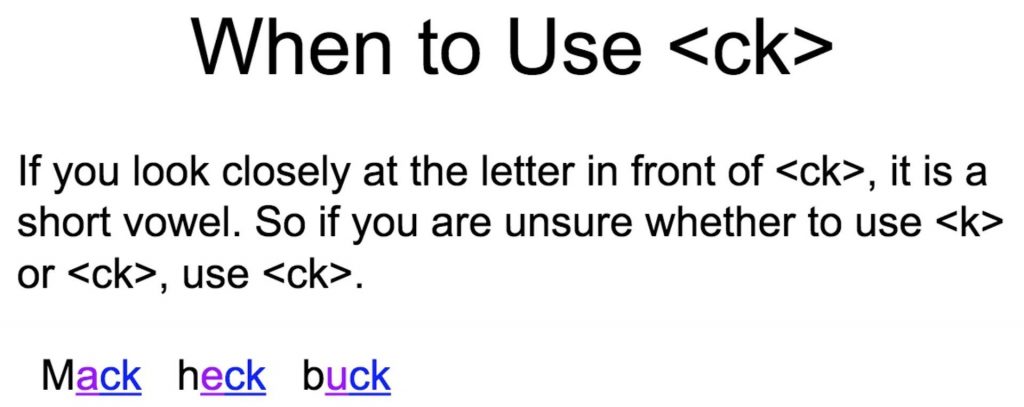

The investigation comparing <k> to <ck> was completed by Ana and was presented on Google Slides, so I am sharing screen shots. We noticed interesting things here! We noticed that <dge>, <tch>, and <ck> were final in the words looked at by the students and were always preceded by a short vowel. Ana noticed that when <k> was final in a word, it was preceded by either a vowel digraph or a consonant. Brayden noticed that when <ge> was final in a word, it was preceded by either a long vowel or a consonant. When the <ge> was preceded by a short <a>, that <a> was part of the <age> suffix.

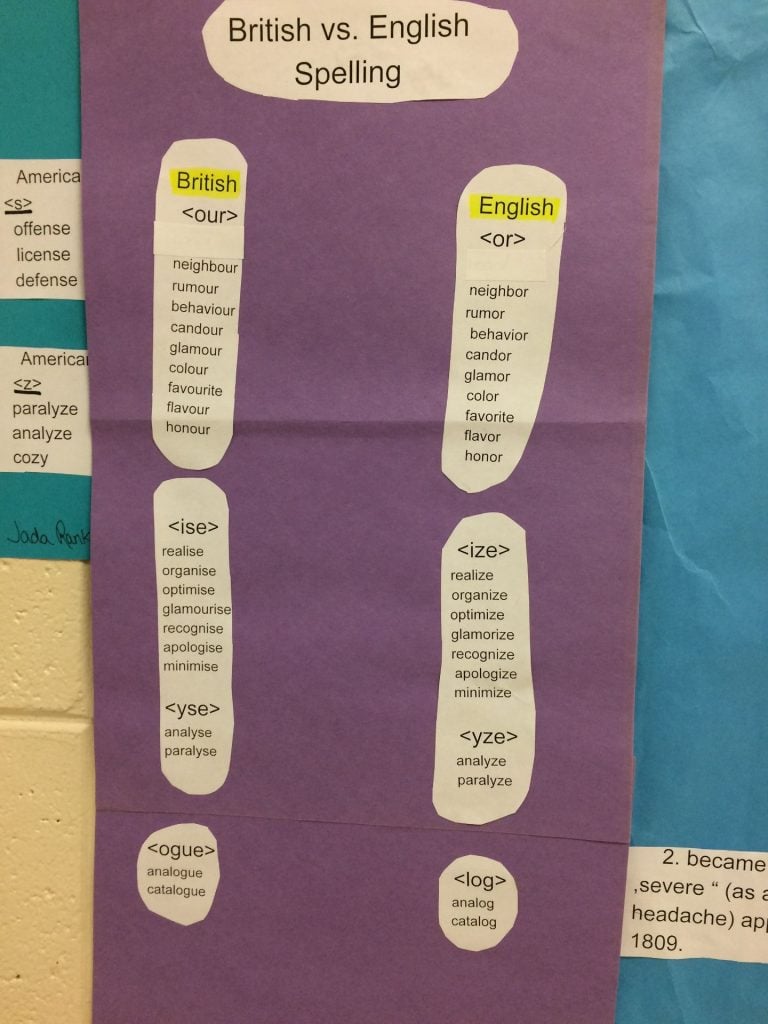

Comparing British English spelling to American English spelling

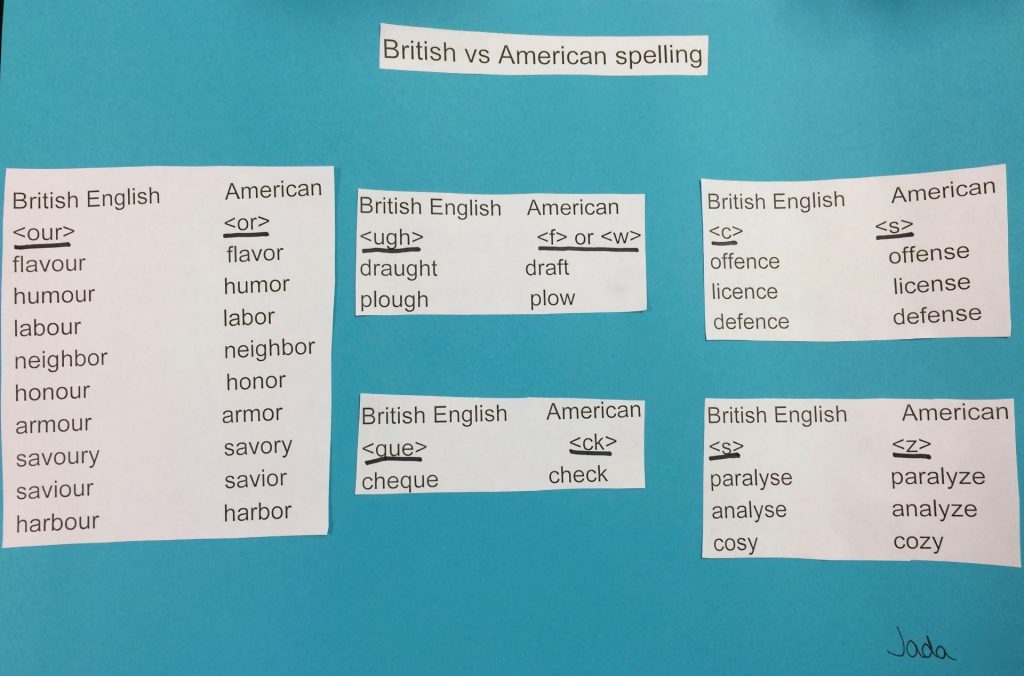

I asked Jada and Natasha to find differences between British English spelling and American English spelling. Most were familiar with the difference between words like favourite and favorite, but were surprised at organise and organize. You can’t see in these pictures, but lower on Natasha’s poster she compared words like centre and center. We have talked about that list of words and how it makes better sense to spell the base with an <re> finally instead of <er>. Think of this word sum using the British English spelling of the base: <centre> + <al> –> <central>. Now think of this word sum using the American English spelling of the base: <center> [<cent(e)r(e)] + <al> –> <central>. We have to think of the base as having a potential <e> both in front of and behind the <r>. Wouldn’t you agree that the word sum using the British English spelling of the base is more elegant and straightforward? Now ask yourself why we have different spellings for British English and for American. The answer is Noah Webster.

In 1807 Noah Webster, who was a very educated man, set out to write a comprehensive dictionary. It was completed in 1828 and called The American Dictionary of the English Language. It was his belief that English spellings were too complex, so he made some changes to certain words and created American English spellings. He preferred color to colour, meter to metre, license to licence among others. He also added American words (skunk and squash) which had not been listed in British dictionaries. He set out to make things easier, but in some ways mucked things up! This is a great reminder that dictionaries are written by real people!

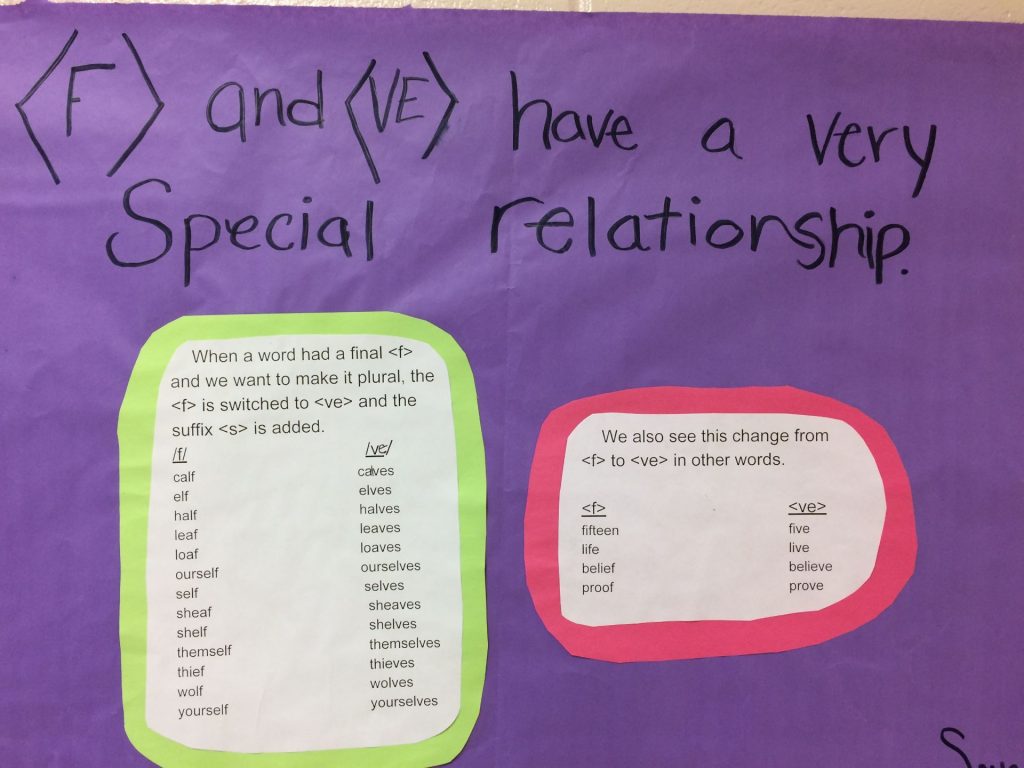

<f> and <ve> have a very special relationship

This was Saveea’s investigation. She started by collecting words that had an <f> when singular but the <f> was replaced with a <ve> when the word was written as a plural. In her search she came across some other words that had one form with an <f> and another form with <ve>. We couldn’t think of others to add to the list at that moment, but we are keeping it in mind and hope to find more examples!

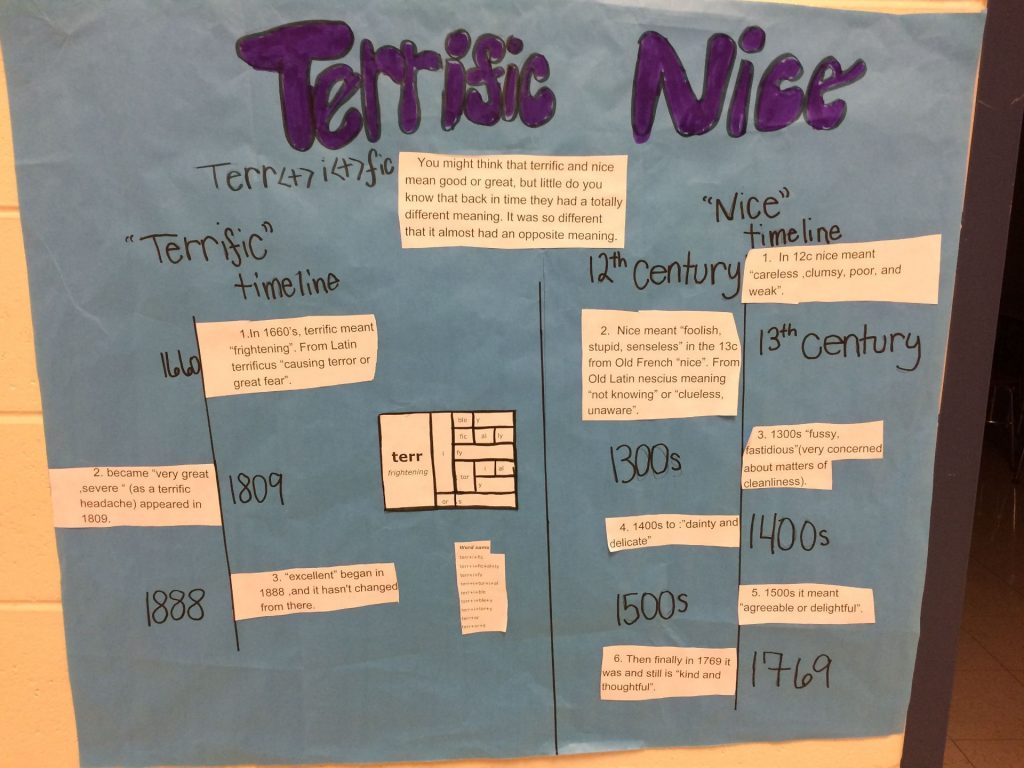

Words whose meaning has changed drastically over time

Petra enjoyed investigating <terrific> and <nice>. She decided that a timeline for each would best tell the story of how the meaning changed over time. If we begin by looking at terrific, we see that in 1660, it meant “frightening”. In 1809 the meaning was more of “very great or severe” as in a terrific headache. By 1888 it meant “excellent” as in a terrific idea! Now when we look at nice, we see that in the 12th century it meant “careless, clumsy, poor and weak”. By the 13th century it meant “foolish, stupid, senseless”. How about that? In the 1300’s it meant “fussy, fastidious”. In the 1400’s it meant “dainty and delicate”. In the 1500’s it meant “agreeable or delightful”. By 1769 it was being used to mean “kind and thoughtful”. Isn’t that a turn around in meaning? Since learning this information, when someone uses the word nice in class, someone else always asks, “Do you mean 12th century nice or present day nice?” We are definitely having fun with these!

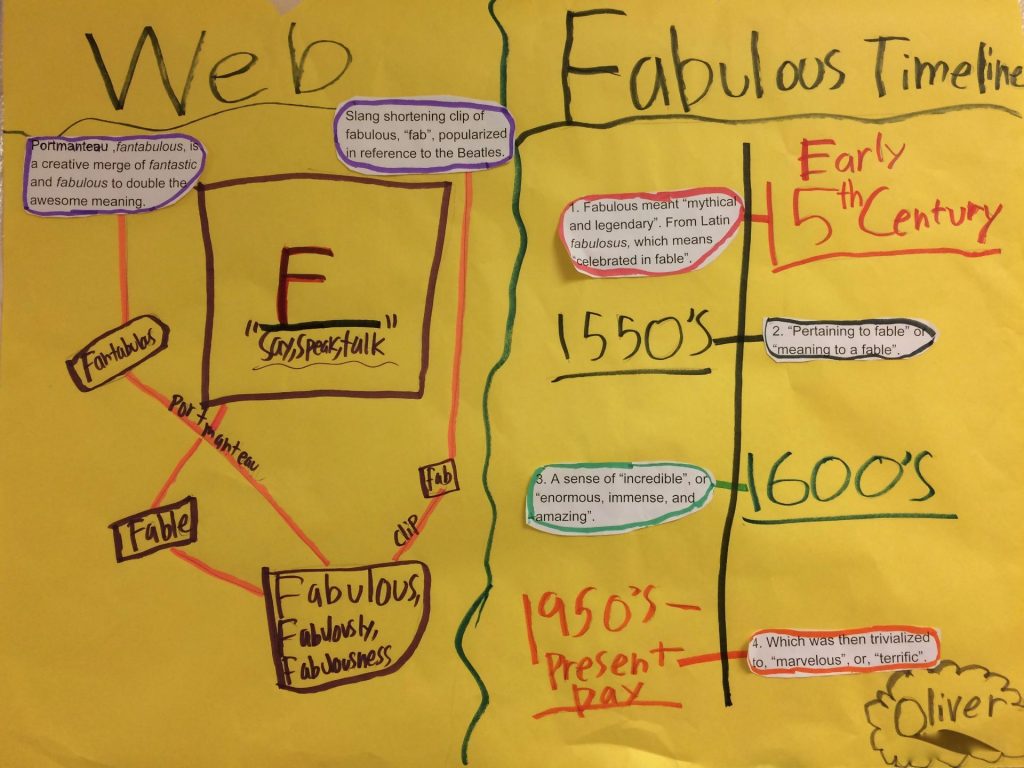

Oliver investigated the word <fabulous>. He found out that in the early 15th century it meant “mythical and legendary”. In the 1550’s it meant “pertaining to fable”. In the 1600’s it took on a meaning of “incredible or enormous, immense, and amazing.” Ever since the 1950’s it has been trivialized to merely “marvelous or terrific”. We had a great discussion about the fact that it was trivialized in it’s meaning between the 1600’s and present day. In the 1600’s, there must have been a feeling of awe surrounding its use that has been lost.

On the left side of Oliver’s poster, he began in the middle with the uniliteral base <f> with the denotation “say, speak, talk” (from Latin fari). Follow the orange line to <fable> which is built from the base <f> and suffix <able>, and then to <fabulous> “that which is celebrated in fable”. Fabulous, fabulously, and fabulousness all share the base <fabul>. At this point, Oliver’s orange lines take you in two directions. The line to the left takes you to the portmanteau <fantabulous>. Oliver enjoyed looking at portmanteau words earlier this year and recognized this one right away. The other orange line takes you to <fab> and let’s you know it is a clip of <fabulous>. If you follow the line to the top, you’ll see the the word <fab> was popularized by reference to the Beatles! From the discussions I had with Oliver during his research, I could easily follow his visual on the left. I hope I’ve helped it be clear to you as well!

We put these investigations on pause when we need to. Earlier this week I asked the students to write their own graduation speech. But within two or three days,as students finish that, they eagerly get back to these. Currently, there are other investigations going on as well. I have students looking at assimilated prefixes, frequentative suffixes, and diminutive suffixes. As you can imagine, each investigation broadens the understanding of how amazing, fascinating, and alive the English language is! These students love investigating because they love learning!