The Cincinnati Zoo & Botanical Garden posted this picture and description a while back. I love it! The hippopotamus really looks relaxed, doesn’t it? As it says in the description, the tilapia fish eat the dead skin off the hippos. This action keeps the hippos clean and free of micro-organisms. The dead skin, along with some hippo dung, keep the tilapia fed. This idea of two organisms living together for the benefit of both is called symbiosis.

The first time I ever encountered an example of symbiosis was when reading a book called Bill and Pete by Tomie de Paolo. The copy we had at home was well worn, signifying if was a favorite!

In the story, Bill is a crocodile and Pete is a bird who cleans Bill’s teeth. The relationship between these two is based on the Egyptian Plover that actually does clean the teeth of crocodiles along the banks of the Nile. Here is a short article from Small Science that explains in more detail the symbiotic relationship between the Plover and the crocodile!

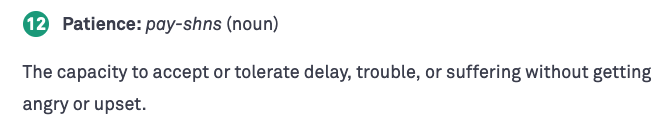

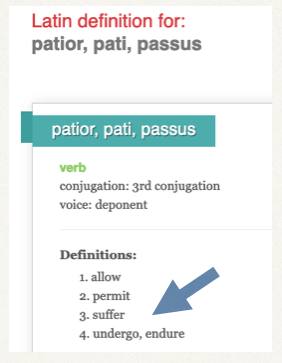

When I took a closer look at symbiosis recently, I learned a lot! In an article published at PBS, Aryeh Brusowankin said, “Symbiosis is defined as a close, prolonged association between two or more different biological species.” I guess that’s what makes the relationship fascinating. How did those two species figure out they had something to gain from forming a relationship? Upon reading further, I found that not all symbiotic relationships are beneficial to both of the participants. The three types of symbiosis are mutualism (benefits both), commensalism (benefits one, no benefit or harm to the other), and parasitism (benefits one, harms the other).

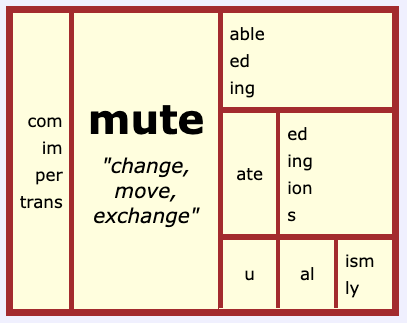

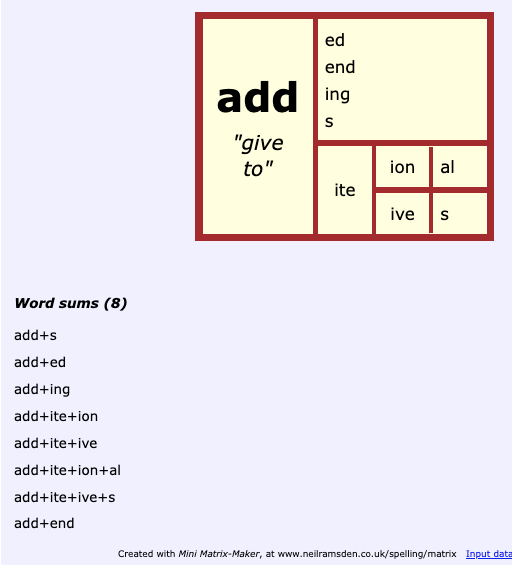

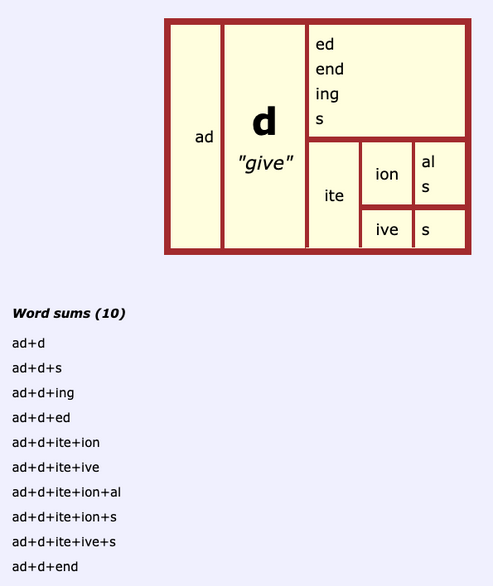

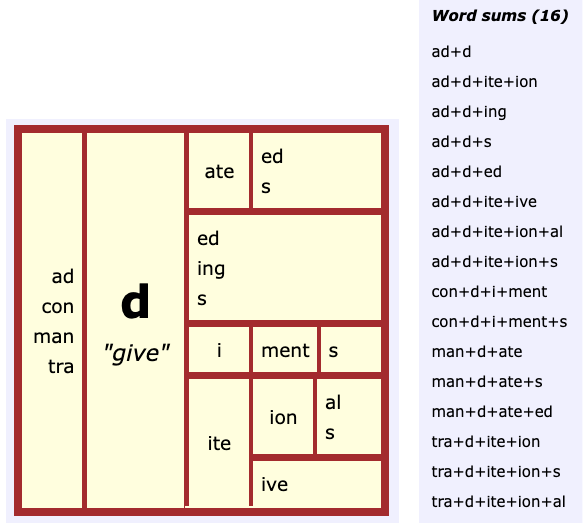

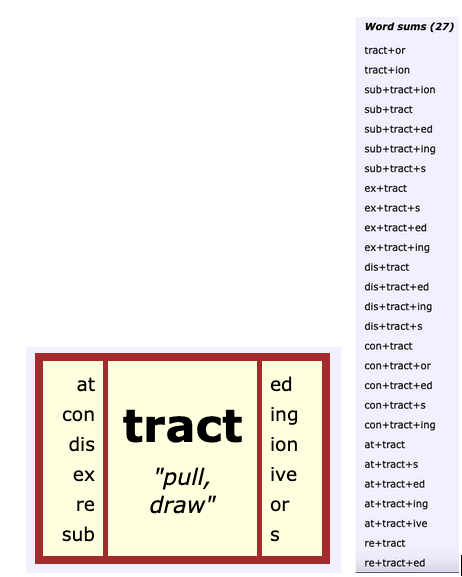

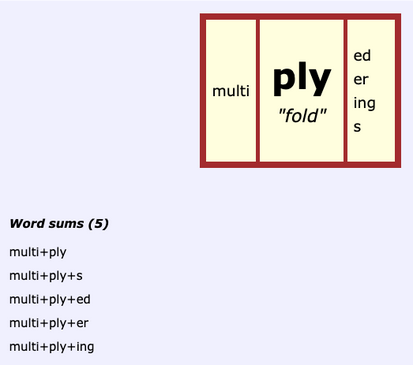

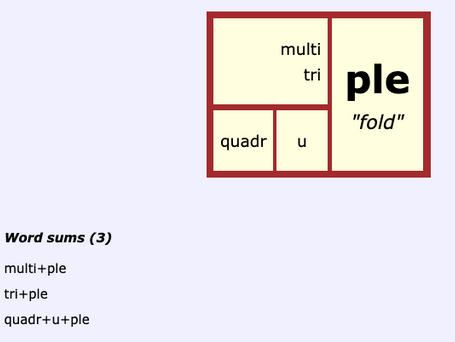

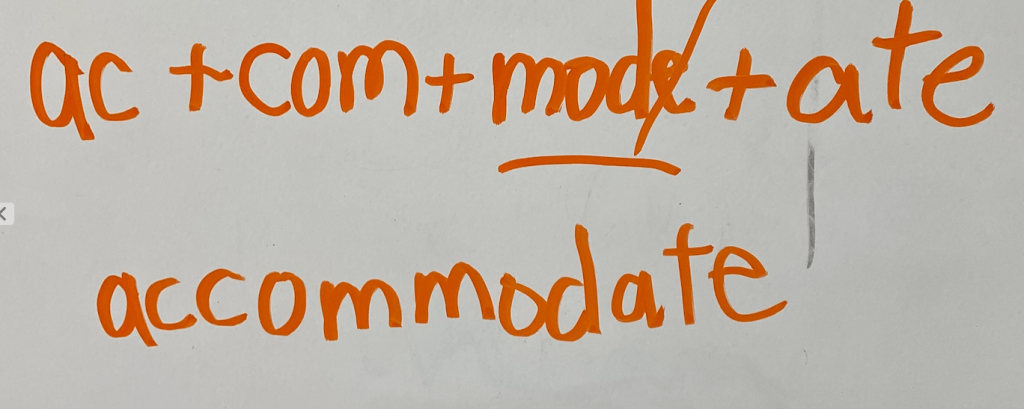

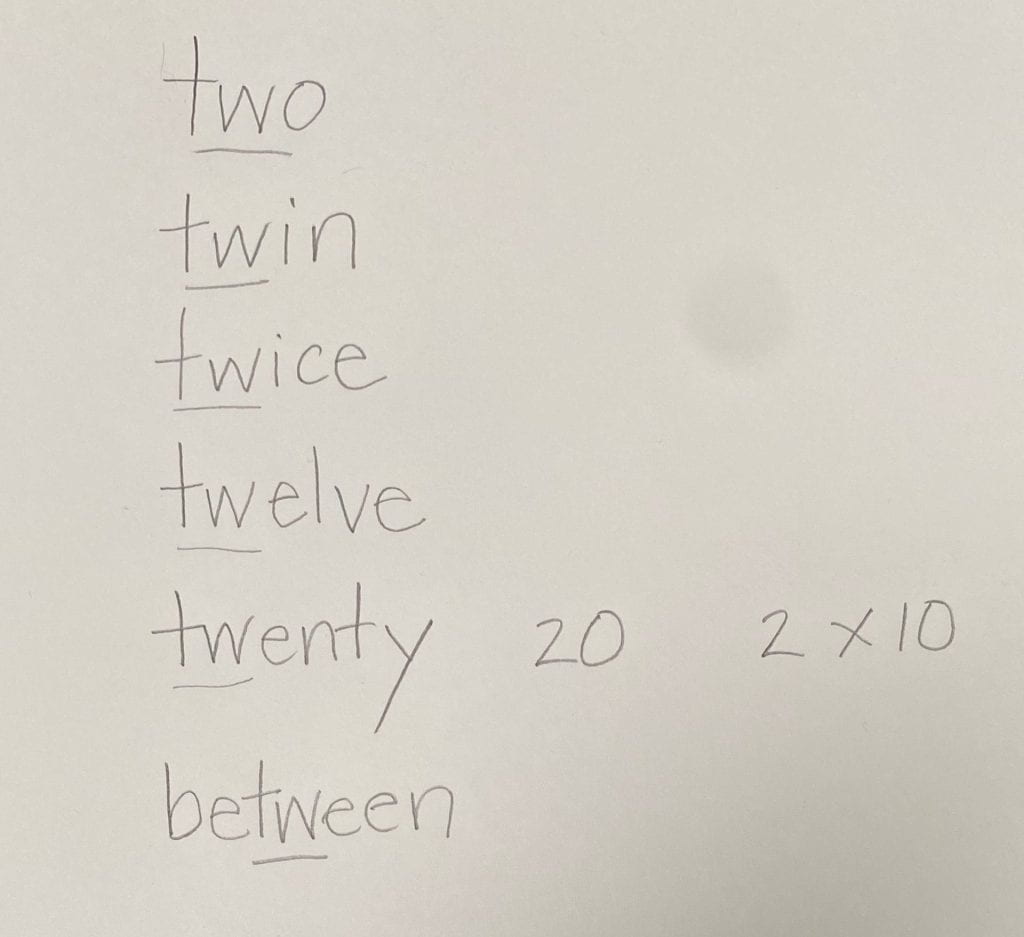

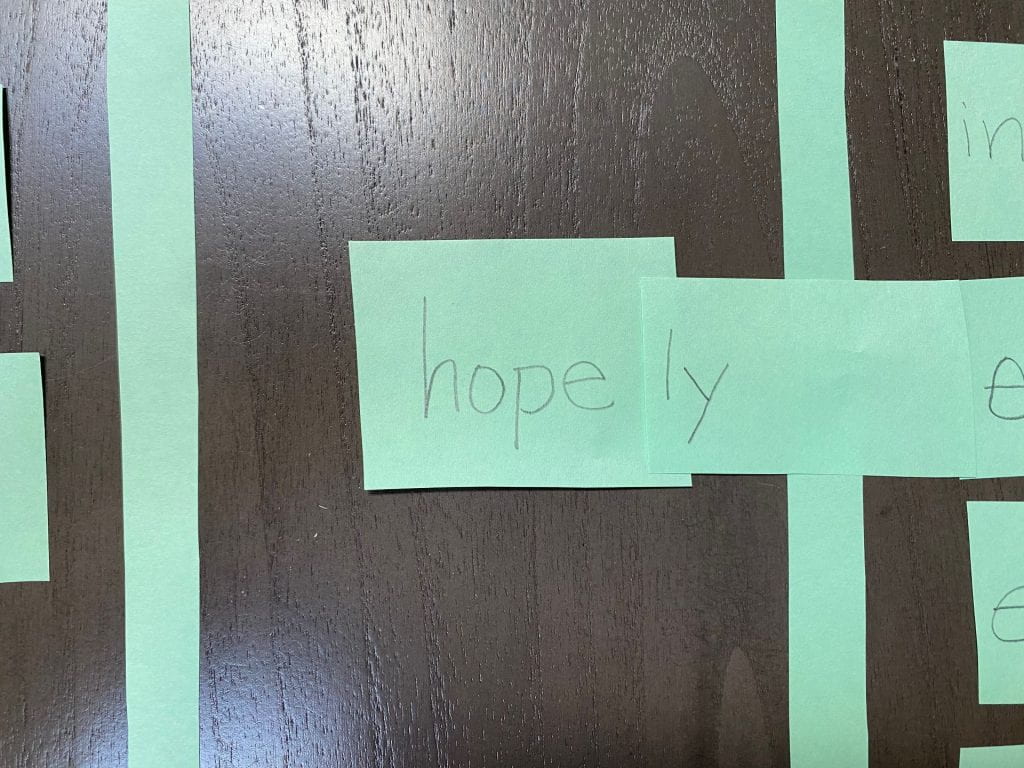

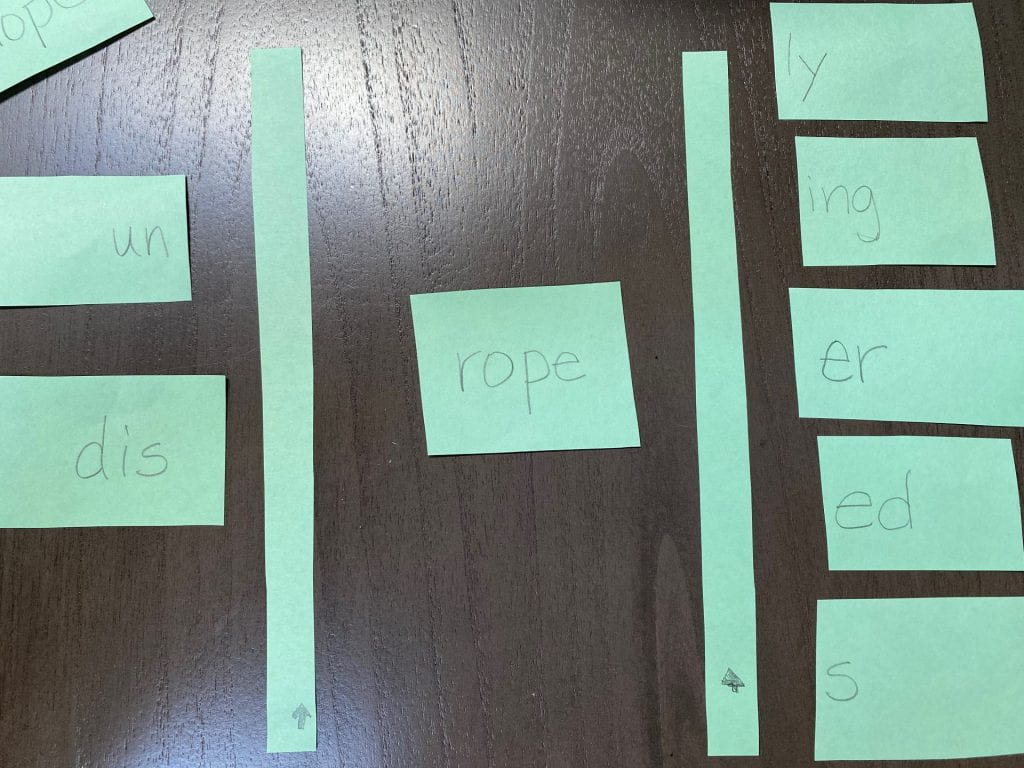

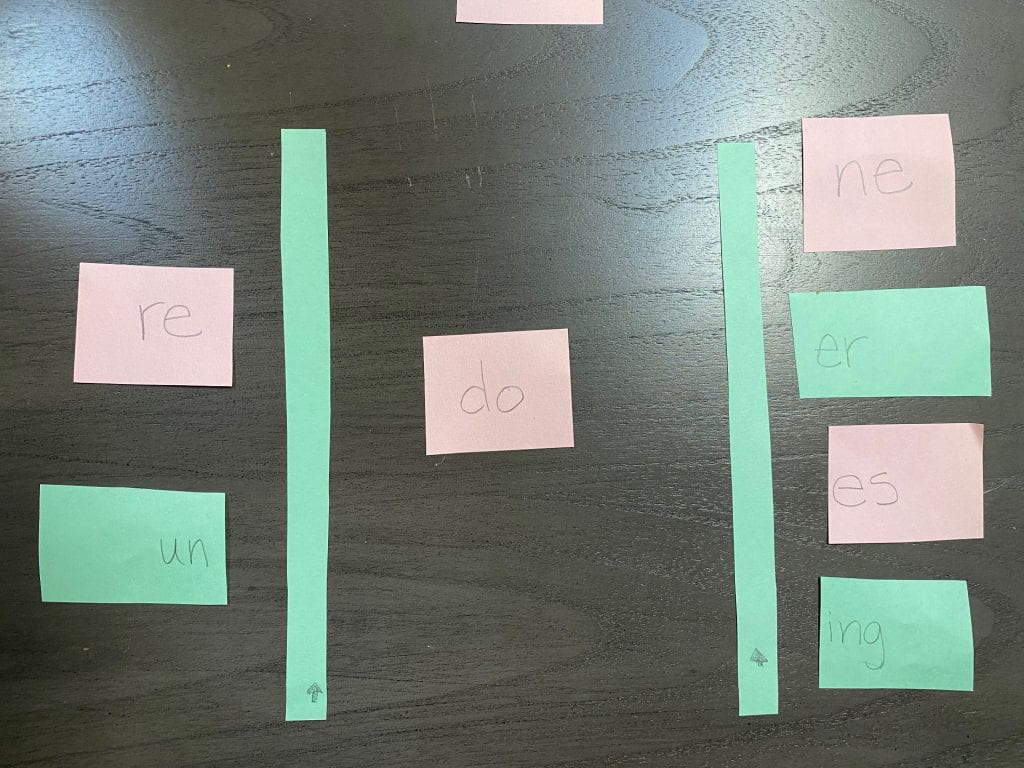

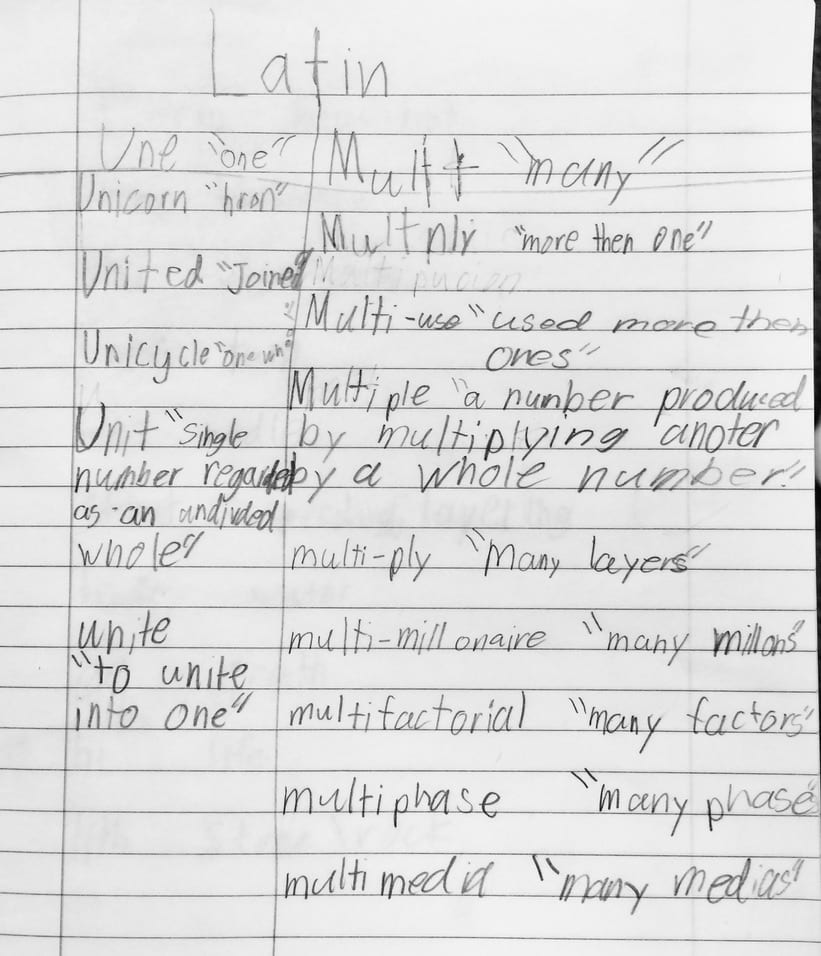

When the species involved benefit, it is called mutualism. Etymonline describes mutualism as, “a symbiosis in which two organisms living together mutually and permanently help and support one another.” As you might recognize, ‘mutualism’ can be thought of as <mutual + ism>. The suffix <-ism> is a noun forming suffix indicating “a practice, system, or doctrine.” But can ‘mutual’ be further analyzed? As it turns out, yes. It derives from Latin mutuus “reciprocal, done in exchange.” Etymonline didn’t offer more, so I went to the OED (Oxford English Dictionary) to see what else I could find out. Here the word ‘mutual’ is listed as being borrowed from French mutuel. The French word derived from Classical Latin mūtuus meaning “borrowed, corresponding, reciprocal.” The OED went on to say that mūtuus shares the same base as mūtāre “to change” and that –uus is an adjective forming suffix in Latin. This information is very helpful to me. I recognize the -are as a Latin infinitive suffix that I can remove. When I do, I am left with the Latin stem mūt. When that stem comes into English, I add the final <e> that we see on many bases from Latin. Now I have evidence to support the word sum for ‘mutual’ as being <mute +u + al>. That makes sense when I think about mutual because I know <-al> to be a suffix (final, regional, racial). I also recognize the <u> to be a Latin connecting vowel that I have spotted in other words as well (gradual, usual, factual). The base is <mute> with a denotation of “change, move, exchange.” Time to collect relatives.

One way to find related words is to search mutare at Etymonline.

mutable

mutate

permute

immutable

mutation

transmute

transmutation

permutation

commute

I also found these etymological relatives. They share the root mutare, but not the present day spelling of the base.

mew

molt

Are you already recognizing how these words have a sense of “change, move, exchange?” Pay attention to the prefixes you see. What sense do they bring? Another site I use when I am looking for related words is Robertson’s Words for a Modern Age. This time I didn’t find any relatives that weren’t already on my list, but I usually do.

A second type of symbiosis.

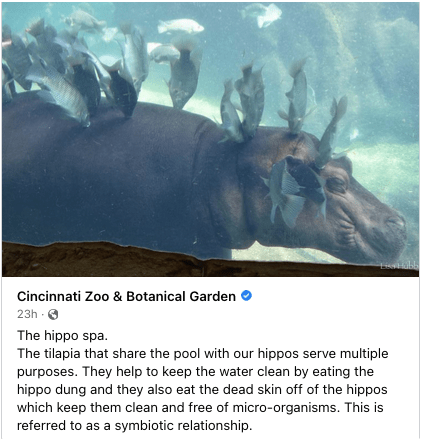

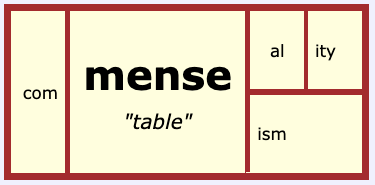

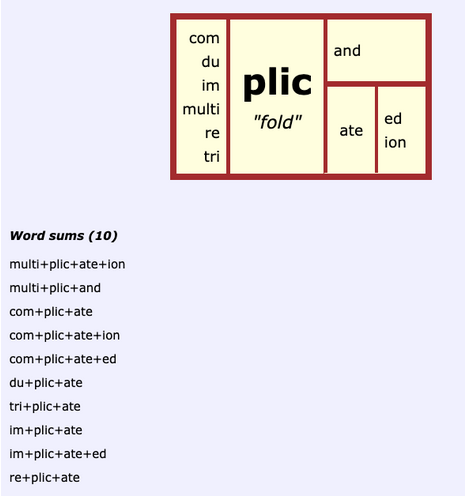

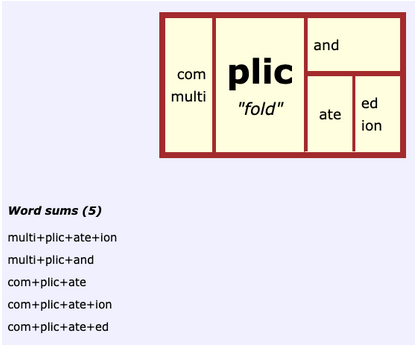

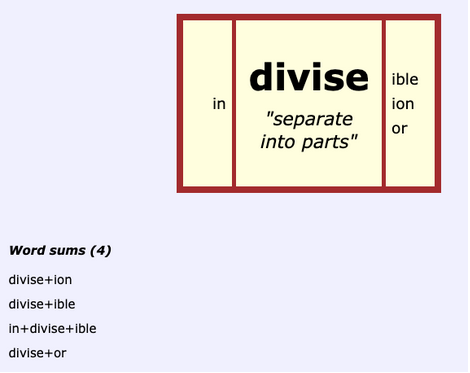

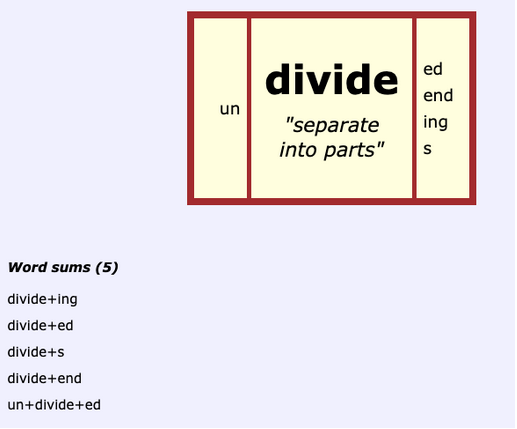

When one of the species in the relationship benefits but the other is unaffected, it’s called commensalism. Now there’s a word I’ve never heard! I wonder if I’m more familiar with other words in the family? Taking a quick look, my word sum hypothesis would be <com + mens + al + ism>. I’m familiar with a <com-> prefix, and both the <-al> and <-ism> suffixes. Etymonline states that this word was first attested in 1870 and at that time meant, “commensal existence or mode of living.” Obviously, I looked at the entry for commensal next. The adjective ‘commensal’ was first attested in the late 14c. At that time it meant, “eating together at the same table, sharing the table with the host.” So the sense of together is in the prefix <com-> and the sense of table is in the base <mens> which derives from Latin mensa “table.” At this point, I wondered about the word ‘table’. (A bit off topic, but if you’re all in with SWI, you love rabbit holes too!)

In the 13c, the Latin word for “piece of furniture consisting of a flat top on legs” was mensa. The noun ‘table’ derived from Old French table, tabel which derived from the Latin tabula “a board, plank; writing table; list, schedule; picture, painted panel.” In that denotation I get the sense that a tabula had many uses. When the word was adopted in Old French, the idea of holding food was added. By the 14c, in English, the word table commonly referred to the place we set food. Since 1750, the use of table has grown. It is now one of the 1,000 most common words in written English according to the OED. The use of mensal however, has dropped and is used 0.01 times per million words in written English. See? It’s the people who use or don’t use words. It’s the people who determine if a word becomes obsolete. It seems as if the word ‘mensal’ is certainly moving in that direction, doesn’t it? There aren’t many words in use that share this base.

commensal

commensalism

commensality

mensal

If you are wondering whether or not ‘commensurate’ would belong on this matrix, you are officially word curious! I wondered that as well. It belongs if it shares a root and a spelling. At Etymonline, we see that commensurate derives from Latin mensus “to measure.” When something is commensurate it is “reducible to a common measure, commensurable” or “corresponding in size or degree.” We have discovered that the base <mens> “table” is homographic to the base <mens> “measure”. There is a bound base <mens> in commensal and a different bound base in commensurate. What this tells me is that looking over a list of words to find a common base must be followed up by a look at the etymology to confirm the root or etymon of those words. Only then can we be confident in our analysis that all of the words on the list share the same base.

An example of commensalism are the remora fish that attach themselves to larger fish or, in this case, a sea turtle. The remora fish feed on the sea turtle’s fecal matter. Other fish, such as the pilot fish, feed on the leftovers from its host’s meal. So the fish benefit and the larger fish, or in this case sea turtle, is neither harmed nor benefited.

By shahar chaikin – https://www.inaturalist.org/photos/241647485, CC BY 4.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=131143186

A third type of symbiosis.

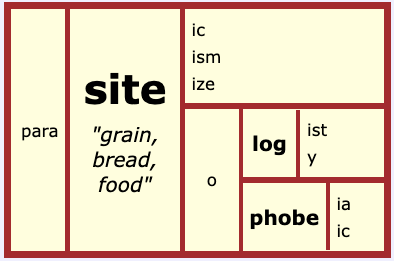

When one of the species is harmed and one is benefited, it is called parasitism. It’s likely that you are already familiar with this one. My word sum hypothesis is <para + site + ism>. I’m familiar with <para-> as a prefix in paragraph and parachute, although that doesn’t guarantee it is a prefix in this word. I recognize <-ism> as a suffix. In fact it is included in both of the matrices listed earlier in this post! Now to find out if there is evidence to support my hypothesis.

At Etymonline, we learn that ‘parasite’ was first attested in 1530. At that time it was used to mean “a hanger-on, a toady, person who lives on others.” (Okay, another quick visit down a rabbit hole. The word ‘toady’. A quick look at my mactionary and I learn this. “Early 19th century: said to be a contraction of toad-eater, a charlatan’s assistant who ate toads; toads were regarded as poisonous, and the assistant’s survival was thought to be due to the efficacy of the charlatan’s remedy.” Fascinating.) Before ‘parasite’ entered English, it was either from French parasite or directly from Latin parasitus “toady, sponger” and directly from Greek parasitos “one who lives at another’s expense, person who eats at the table of another,” especially one who frequents the tables of the rich and earns his welcome by flattery.” This interests me. Whenever I’ve heard of a person referred to as a parasite, I assumed it was in likeness to an organism (plant or animal) being a parasite to another organism. Now I find out it is the other way around! It wasn’t until 1640 that a parasite meant “a plant or animal that lives in or at the expense of another.”

At the same entry we see that <para-> “beside” is the prefix and the base <site> “grain, bread, food” derives from Greek sitos. So the literal meaning of ‘parasite’ is “feeding beside.” That almost sounds friendly, doesn’t it? Except in this relationship, one is the host and the other is the parasite. There is harm to the host and benefit to the parasite.

When my children were about six and eight, we found a caterpillar. We knew it wasn’t going to be a Monarch, but were still excited to wait and see what it would be. My husband, who is an entomologist, took one look at it and said it would never become a butterfly. We were alarmed. “What do you mean?” He pointed to some eggs that had been laid on the surface of the caterpillar. He said they were laid by an Ichneumonid wasp. What would happen is that those eggs would hatch and eat the caterpillar from the inside out. Clearly the caterpillar was the host and the wasps benefited. I read recently that when caterpillars threaten to destroy a crop, these types of wasps have been used by farmers to control them.

A cowbird is an example of a brood parasite. It lays its egg in the nest of another species of bird. In other words, the cowbird leaves the raising of its offspring to someone else!

By Galawebdesign – Own work, CC BY 3.0, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4200741

I searched Etymonline to find words related to the base <site>. I specifically searched for sitos which is the Greek root. Then I went to Robertson’s Words for a Modern Age and found more.

sitophobia

sitology

parasite

parasitize

parasitism

parasitic

parasitology

parasitologist

An etymological relative I spotted.

salary

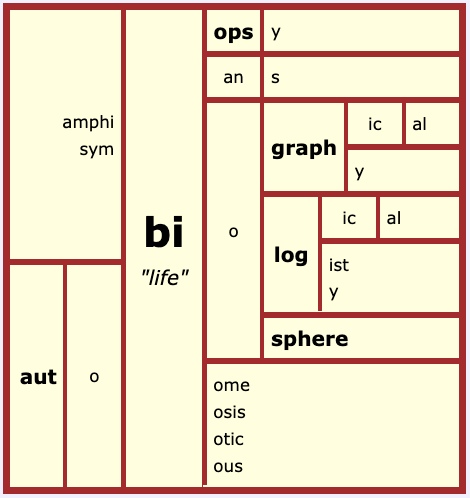

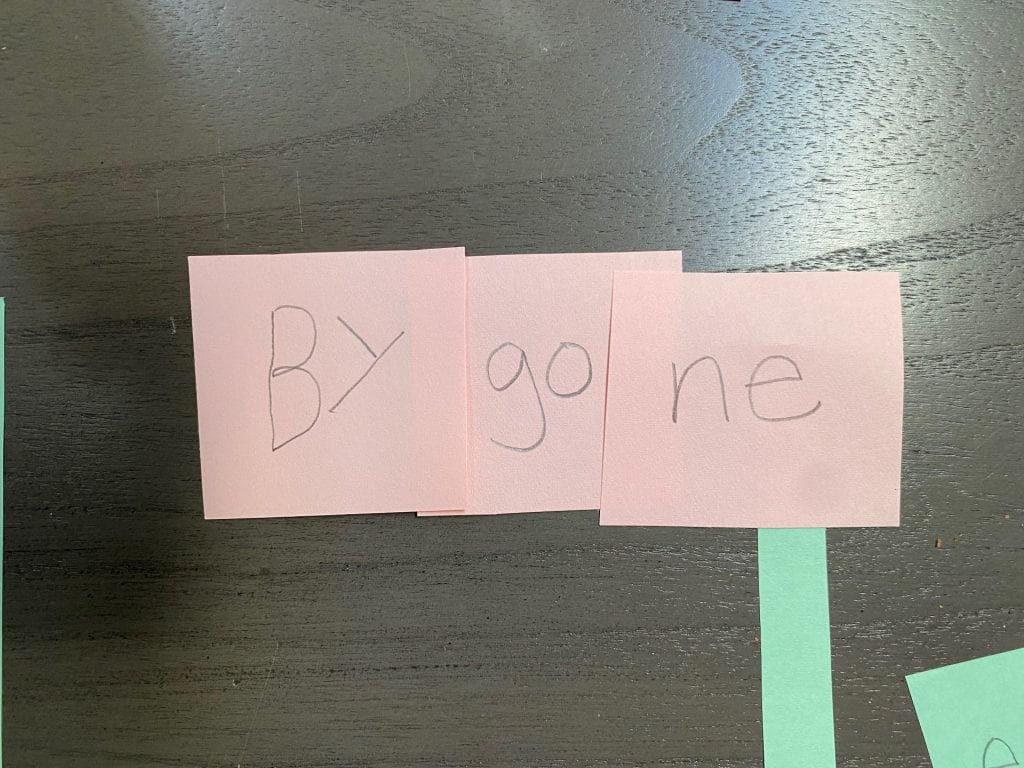

Now that we’ve looked closer at the three types of symbiosis, let’s take a look at symbiosis! I certainly have a good understanding of what it is at this point. If you look back through this post, you’ll find that I either used ‘symbiosis’ or ‘symbiotic’ when discussing this topic. Does looking at both of those help me hypothesize a word sum? I recognize that <sym-> can be a prefix. I’ve seen it in symphony and symmetrical. I recognize that <-ic> can be a suffix. I’ve seen it in iconic and atomic. But if <sym-> is the prefix in symbiotic and <-ic> is the suffix, what is the base? Etymonline, here I come!

It is an adjective as I suspected (-ic usually signals that). Interestingly enough the entry says, “from stem of symbiosis + -ic.” So what is the stem of ‘symbiosis’? I’m following the bolded link. First attested in 1876. The date tells me that scientists created this word to describe what they were seeing. They went back to Classical Latin and Greek languages to use bases and words that would be widely recognized when naming a scientific idea. Symbiosis derived from Greek symbiosis which is from symbios “(one) living together (with another), partner, companion, husband or wife.” The prefix <sym-> is an assimilated form of the <-syn> prefix “together.” The fact that it is an assimilated form just means that <-sym> better matches the articulation of the next element than <syn-> does. Say *synbiotic a few times quickly and you’ll notice that your mouth corrects it to ‘symbiotic’. Or slowly pronounce the flow from <n> to <b> and then <m> to <b>. You’ll find one transition is smoother.

So if the prefix is <-sym>, what’s the rest of the word sum? What follows after the information about <sym->, is that the base is from bios “life.” I recognize the ‘os‘ suffix as indicating this word was a noun in Greek. Before I removed it, however, I confirmed that information in the OED. Now I can remove the ‘os‘ and see that the Greek stem ‘bi‘ came into English as the base <bi>. Next I searched Etymonline to see if <-osis> is a suffix. It is. It is used to denote “state or condition.” When used in medical terms, it denotes “condition of disease, disorder, excess, or infection.”

<sym + bi + osis>

So is <otic> also a suffix? Hmmm. I couldn’t find information to support that at Etymonline, but at the OED, I found what I was looking for. <-otic> was first attested in loanwords from Greek adjectives in ‑ωτικός (-otikos), the earliest being narcotic. Formations in English began in the 17th century (hypnotic, exotic, patriotic). In Classical Greek adjectives with ‑ωτικός (-otikos) and nouns with ‑ωσις (-osis) were built off the same verb. That is why we still see an association between words with those two suffixes (symbiotic, symbiosis, neurotic, neurosis, hypnotic, hypnosis). See how etymology can help us understand the bigger system of English spelling?

What other words share this <bi> base from Greek? I searched for bios at Etymonline.

symbiotic

symbiosis

biology

biography

biopsy

biotic (easier to see this structure now, isn’t it?)

biome

amphibian

amphibious

biosphere

Etymological relatives include

microbe

aerobic

I went to Robertson’s Words for a Modern Age and found 21 pages of words related to Greek <bi> “life”! Most were scientific words I was unfamiliar with, but there were many I recognized. I don’t have to include all the words I find, so I’ll leave my matrix at this.

Are you wondering about words like bifocals and bicycle? They have <bi> in them as well. The <bi> we see in bifocals, bicycle, biceps, and biathlon is from Latin and brings a sense of “two” to the word.

Reflections

If we had just looked at the word ‘symbiosis’ in a dictionary, we would have understood what it was. But now our sense and understanding is so much richer! And just think of how we have opened our thinking by looking at related words. When you see any of these morphemes in another word, perhaps it will stand out to you more than it has in the past. We have learned new words and revisited familiar words, but with a deeper understanding. I hope that some of the etymological relatives have intrigued you and perhaps sent you into one of those rabbit holes this kind of work inspires.

When I titled this blog post, just for fun I googled “a symbiotic relationship with words.” The following is an AI response to that. I’d say it is pretty spot on!

“A “symbiotic relationship with words” means a close, mutually beneficial connection with language, where the individual draws inspiration, meaning, and power from words, while also actively shaping and contributing to their usage and understanding, essentially “living together” with language in a way that enriches both the person and the words themselves.”