Following our recent performances of The Photosynthesis Follies, I gave a test. After all, the students had been living and breathing their photosynthesis script for two and a half weeks. I was confident that if they participated and thought about what was happening in our play, they would understand this incredibly important process. They did remarkably well! But that is not the point of this post.

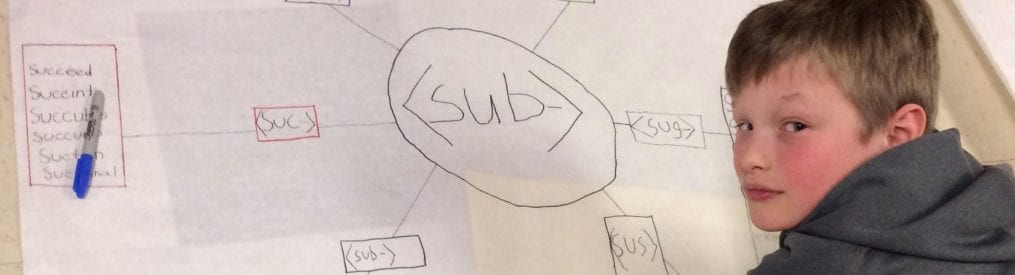

As I always do, while I was correcting the tests, I was taking notes about sentence structures that needed attention and common spelling errors that needed to be addressed. I began to notice how many different spellings were used for the word <xylem>. But within a short amount of time, the number of different spellings for <xylem> was surpassed by the number of different spellings for <oxygen>. As I looked over the spellings, it struck me that my students actually know quite a bit about graphemes and the phonemes they can represent. I thought it might be interesting to specifically look at these two lists.

At the top of each list the word is represented by IPA and the symbols are surrounded by slash marks. The slash marks indicate that this is a pronunciation and NOT a spelling. I wanted the students to think about each word’s pronunciation and how each phoneme in the pronunciation is represented by a grapheme in the word’s spelling. To that end, I underlined each phoneme in the IPA representation of the word <xylem>.

Right away someone asked about the spelling in which there was an <e> in front of the <x>. I put that question out to the students. “Can anyone think of why someone might have put that <e> there?”

“Perhaps it’s because of the way we pronounce the letter <x> when it’s by itself.” That made a lot of sense to me. After all, during play rehearsals, we had a few students that kept pronouncing xylem as /ɛgzˈɑɪləm/. Since the word began with <x>, those students wanted to pronounce it like we do in /ˈɛksɹeɪ/ (x ray).

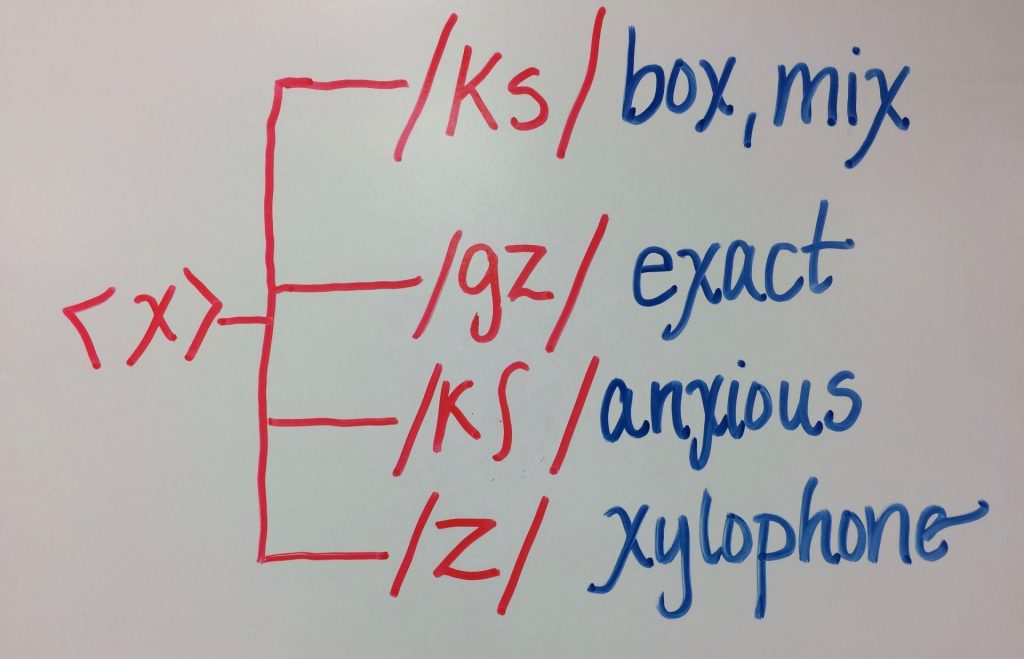

At this point I pointed to what I had written on the board as pertains to the grapheme <x>:

We looked at the various pronunciations that are represented by the letter <x>. We pronounced them aloud and felt the difference between the /ks/ of box, the /gz/ of exact, and the /kʃ/ of anxious. Taking the time to pronounce and feel these pronunciations in our mouths was an eye opener for my students. When all you remember being told is that “x is for x ray”, you’re at a disadvantage when trying to read and spell words with an <x>!

When we looked at the fourth phoneme that could be represented by the grapheme <x>, /z/, we recognized that not only was that the way we pronounced <x> in xylophone, but also in xylem! We turned our attention back to the list.

We looked specifically at the unstressed vowel known as the schwa in IPA. I reminded the students that some of them had this schwa as part of the pronunciation of their name. They offered that the schwa, /ə/, is sometimes represented by the grapheme <i> as in Jaydin, by the grapheme <a> as in Amelia, by the grapheme <e> as in Kayden, and the <o> as in Jackson.

So with that in mind, we looked at the choices students had made in choosing a vowel to precede the final <m>. Students chose either an <a>, an <e>, or a <u>. This was in keeping with what we understand about the schwa. I also reminded everyone that the schwa represents an unstressed vowel. That meant that the other vowel in this word, represented by /ɑɪ/, would be carrying the stress. And sure enough, when we announced the word over and over, the stress was on the /ɑɪ/.

Looking back at the list, there were only two graphemes chosen to represent the /ɑɪ/. It was either an <i> or a <y>. I wondered aloud if it was possible for a <y> to represent /ɑɪ/. Students named words like sky, xylophone, and cry to provide the evidence that it could.

So when we now looked at our list, we realized that only three of the spellings made sense and were possible — the first (*xilam), the second (*xilem), and the last (xylem). The third, fourth, and sixth were missing the grapheme that paired up with the phoneme /ɑɪ/.

So now what? Now it was time to check into this word’s etymology. Looking at Etymonline, we see that it was first attested in 1875, meaning “woody tissue in higher plants”. It was from German xylem, coined from Greek ξύλον, transcribed as xylon “wood”. This was particularly interesting to us because we were focusing on the water that is transported in the xylem. Now we knew that the xylem itself was made of woody tissue and helped physically support the plant or tree! According to the Encyclopedia Britannica, only the outer xylem (sapwood) is active in transporting water from the roots to the leaves. The inner part of the tree (heartwood) is made up of dead xylem that no longer carries water, yet is strong and gives the tree that physical support. The next time you count the rings on a cross cut piece of a tree, know that you are counting rings of xylem!

Here’s an easy way to see the xylem tubes in a piece of celery.

And just in case you are interested, the word xylophone was also coined from xylon “wood”. The xylophone consists of wooden bars struck by mallets.

Getting back to the spelling of xylem, we also noticed that the vowel following the <x> has been a <y> all the way back to Greek! As a matter of fact, seeing a <y> medially in a word is an indicator that the word is from Greek!

The only grapheme yet to check was whether the unstressed vowel preceding the final <m> was an <e> or an <a>. At Dictionary.com I found out that xylem was from <xyl> “wood” + <ēma >. The entry also said to “see phloem”. Interesting! So the second part of this word is the same as the second part of the word phloem. Still at Dictionary.com, I found out that the second part of the word phloem is <-ēma >, a deverbal noun ending. A deverbal noun is a noun that was derived from a verb. Etymonline also listed <-ema> as the suffix in the word phloem.

So we now have evidence to support that <xylem> is the way to spell this word. We also have an understanding of so much more!

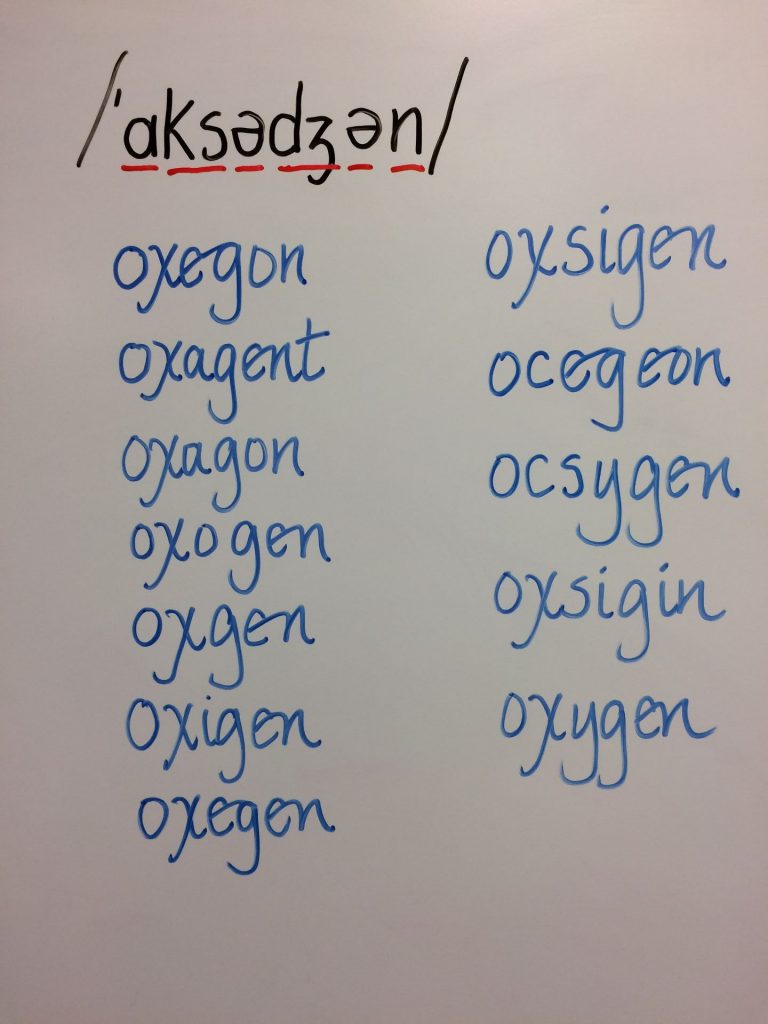

It was time to look at the IPA for <oxygen> and see what we could learn.

I again underlined the phonemes in the IPA that would represent a grapheme in the spelling of the word. We noticed that everyone chose <o> to represent /ɑ/. The next phoneme was /ks/. There were only two spellings that had something other than an <x> to represent this. I asked if choosing a <c> or a <cs> made sense. The students recognized that a <c> can sometimes be pronounced /k/, so we could understand someone choosing <cs>. The <c> by itself, however, could not represent the phoneme /ks/. We could rule that spelling (*ocegeon) out. We also noticed that two of the spellings had <xs> as representing /ks/. This brought us back to our discussion of expire from the other day. We knew the <ex-> was a prefix with a sense of “out” and the base is from <spire> meaning “breathe”, but that when joined together, the <s> on the base was omitted or elided to make the word easier to pronounce. Now we could also rule out the spellings *oxsigen and *oxsigin.

AUTHOR’S NOTE: A friend emailed me regarding this post and in particular, the above paragraph. We are now both curious about instances in which the prefix <ex->is followed by <s>. There are a few older words (very few) like exsanguine (bloodless) and exscind (cut off or out) where we see this letter combination. Perhaps it was more common a while back and moving forward in time, the <s> in many of the words was elided. I’m not sure. My take away is that I don’t have to have the precise answer right now. It is something I will keep in mind as I encounter other words. In the meantime, I am also contemplating words in which the <ex-> prefix is followed by a base with an initial <c> as in <exciting>. We know that the <c> (when followed by <e>, <i>, or <y>) is pronounced /s/. So why is it that very few words follow the prefix <ex-> with an element that has an initial <s> for pronunciation’s sake, yet many words follow an <ex-> prefix with an element that has an initial <c> that is pronounced as /s/? Interesting questions, right? Well, as a very good friend says quite often, “There are no coincidences!” That very question was asked in a scholarly group I was part of today! Just because the <c> (when followed by <e>, <i>, or <y>) is pronounced /s/ in Modern English spellings, doesn’t mean it follows that convention in other languages, or that it did in Latin. So the <ex-> prefix followed by an element with an initial <c> didn’t (and in many languages still doesn’t) present the same pronunciation situation that <ex-> followed by an element with an initial <s>. What an elegant explanation!

Back to the post:

The next phoneme in the pronunciation was a schwa – an unstressed vowel. We knew from our look at xylem that several letters could represent /ə/. There was one spelling that was missing the representation of this vowel. We could take that spelling off the list of possibilities (*oxgen). The rest of the letters used to represent /ə/ could be used, so we kept going.

The next phoneme in the pronunciation was /dʒ/. The students pronounced it and noticed that every spelling left represented /dʒ/ with the grapheme <g>, even though it could also be represented with <j>.

It was time to look at the second /ə/ and again recognize that this pronunciation can be represented with many vowel letters. It was interesting to note that almost all of the spellings used an <e>. Only two spellings used an <o>. I asked if anyone could think of words with a <gon> at the end. Students thought of polygon, dragon, and wagon. We wondered if following a <g> with an <o> and a <n> would always result in the <g> being pronounced as /g/ instead of /dʒ/. If that was the case, the grapheme <o> wouldn’t work in this position in this word.

When looking at the final phoneme /n/, we noticed everyone chose the grapheme <n>to represent it. That is, all except for the spelling with the final <t>. Students offered theories about why someone might think there was a /t/ pronounced finally, but in the end we decided that was not the spelling we were after, and we could eliminate it as a reasonable choice.

It all boiled down to the first /ə/. If we could find out which grapheme represents it and why, we will have found the logical spelling choice for this word. Here were our final choices:

oxogen

oxigen

oxegen

ocsygen

oxygen

It was time to search our etymology resources! There must be information in this word’s history that will lead us to the current spelling.

At Etymonline we found out that this word was attested in 1790, referring to “a gaseous chemical element”. It was from French oxygène, coined in 1777 by the French chemist Antoine-Laurent Lavoisier. It was from Greek oxys “sharp, acid” and French <-gène> “something that produces”. The French <-gène> was from Greek <-genes> “formation, creation”. The denotation of the <oxy> part of this word doesn’t seem to make sense until you know this word’s story. At the time this word was coined, it was thought that oxygen was essential in the formation of acid (hence it’s name meaning something that produces acid). We now know that isn’t the case. Isn’t that interesting?

As usual, the etymology added a lot as far as understanding the spelling of this word. We found out that the <x> is the letter to represent /ks/ and the <y> will represent the /ə/. That eliminates all spellings except <oxygen>. Pretty cool, huh?

When all was said and done, we noticed one more thing. In the word <xylem>, the <y> was stressed and pronounced /ɑɪ/. In the word <oxygen>, the <y> was unstressed and pronounced /ə/.

There are many reasons I chose to take a closer look at these misspellings. One of the biggest was that of letting my students know that they know a lot about graphemes and the phonemes that they represent. So often a student will feel bad when they misspell a word. Well, today I wanted to celebrate the logical thinking they do when they are thinking of how to spell a word. But I also wanted to point out that without etymology, we can only go so far. After that it becomes a guessing game.

I filmed this lesson with my first class. It is similar to what I have described here, although what I have written here is an overall impression from my experiences talking about this with three classes.

Latin had no ‘soft c,’ so Latin words like excitare or excessus would not have had two consecutive [s]’s; that ‘c’ would have been pronounced as a velar plosive, not an alveolar fricative.

Words like exsanguine or exsert or exscind are Modern English coinings from Latinate parts, not Latin words. The elision of the stem-initial ‘s’ happened IN LATIN, not just in Latinate words. You said, “There were Latin words in which this was the case.”

No, there were not.

Time matters when you’re talking about history.