Almost all of the students have presented the Latin verb poster they put together. We have had wonderful and rich discussions with each one. And as we talked we noticed that not all Latin etymons became productive modern English bases. Some of the bases we identified are found in a remarkable number of words while others are found in only a few.

For example, the twin bases <mote> and <move> are two that have become very productive in English. My students can easily name words like remote, demote, promote, motion, emotion, motor, motel, movement, remove, moving, removal, movable and immovable. That is certainly not a complete list, but it does demonstrate how common these two bases are.

Some of the Latin etymons became modern English bases that have not become very productive. Take the Latin verb frango, frangere, frego, and fractus for example. By removing the Latin suffixes on the infinitive and supine forms of this verb, we get the Latin etymons <frang> and <fract>. The modern English bases that are derived from those etymons are spelled exactly the same! You will no doubt recognize the following group of words with <fract> as the base: fraction, fracture, fractal, refractive, diffraction, and infraction. But the only words my students found that share the <frang> base are frangible and refrangible. See what I mean? In English <frang> has not become a very productive base.

Since we have lined our hallway with Latin Verb posters, all we had to do was take a walk in order to identify those very productive modern bases! We chose ten. Some are twin bases and some are unitary. We have decided to spend time looking at the words in these ten families and seeing what else we can notice.

We began with the bases <lege> and <lect>. The denotation of these twin bases is “to gather, select, read”. I asked the students to get out a piece of lined paper. I read some words from this family and asked them to do two things. They were to write the word and they they were to write the word sum, keeping in mind that the base would either be <lege> or <lect>. Some of the words they wrote down were lecture, select, lectern, collection, election, legion, legible and legibly. The next step was for the students to come to the board and write the word and word sum up there so we could look at it and talk about it.

One of the first things I noticed was that someone wrote the word sum for <lectern> as <lect> + <urn>. I wonder if that is a result of misguided practice in which students have been asked to search for a word within a word. If this word was split into syllables, it might just be seen as ‘lec – turn’. Anyway, I adjusted the suffix to read <ern>. Then the students helped me list words with that suffix. I got them started with lantern and cavern. They added eastern, western, govern and modern. Even though most knew that the suffix in <lecture> was <-ure>, we still brainstormed other words that use that suffix like treasure, pleasure, measure, nature and capture.

A third interesting thing to discuss was the way most students used an <-able> suffix in <legible> instead of an <-ible> suffix. One certainly can’t choose which to use based on pronunciation! I asked for <-able>/<-ible> to be written on the Wonder Wall. I have more information in a Smartboard presentation and will show it next week.

The most important thing of all, though, was how the students felt when they saw that they could spell these words when they concentrated on the morphemes. They didn’t have to struggle with thinking about all the letters at once! Instead they focused on each morpheme as it came and the spelling fell into place!

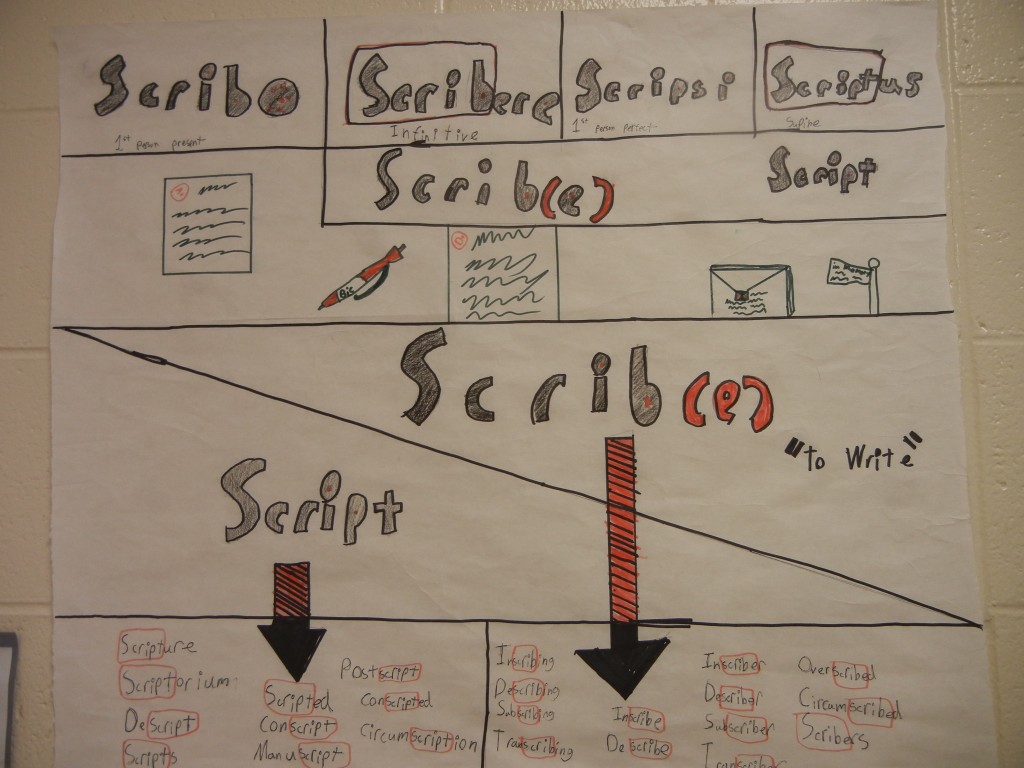

Yesterday when the students walked in the door, I had <scribe / script> on the board with its denotation “to write”. I didn’t even have to ask them to get out paper. They sat down and quickly pulled out paper and pencil. I read words like describe, subscription, prescriptive, scribble, scripture, subscribe, and scriptorium. More students volunteered to write their word sums on the board than had volunteered yesterday! They were enjoying seeing what they could figure out.

With this collection, we had the opportunity to talk about the way the <t> (final in the base <script>) represented a different sound in <prescriptive>, <subscription>, and <scripture>. I’m sure that in their minds (until yesterday) the letter <t> represented only one sound – /t/. When I saw that a boy in the front row had spelled <subscription> as ‘subscripshen’, I said out loud, “Wouldn’t it make sense for someone who has been told to sound out words when spelling to use an <sh> in <subscription>? But look what is really happening. The pronunciation of the letter <t> can be altered by the first letter of the suffix.” We all said the three words so that we could feel the difference in pronunciation. We talked about how some people pronounce <scripture> as if there is a <ch> following the <p> and some people pronounce it as if there is a <sh> following the <p>. Another great opportunity to prove to the students that spelling is not about pronunciation. It is about meaning!

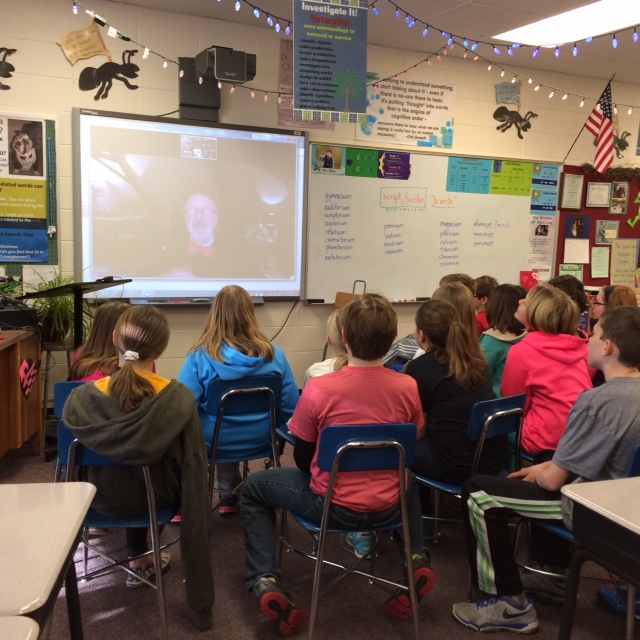

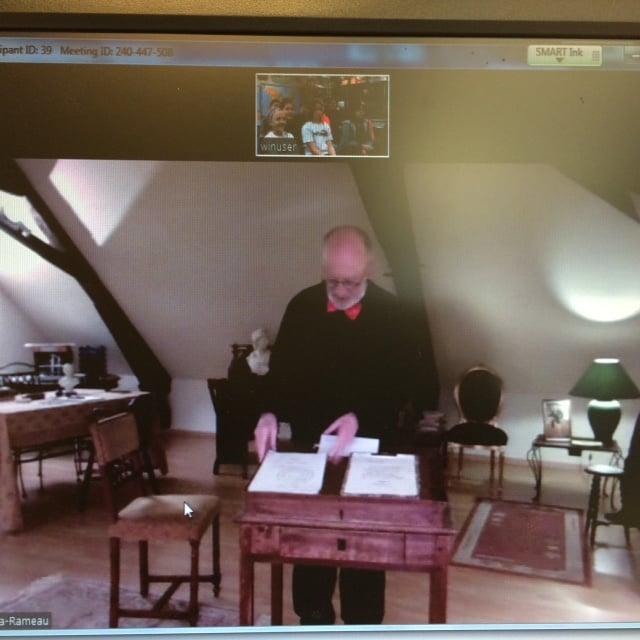

An additional highlight with these particular twin bases (besides the students smiling at their increased level of successful today!) was the word sum for <scriptorium> that someone had written on the board. It was written as <scriptorium> –> <script> + <or> + <i> + <um>. I wasn’t so sure about there being a connecting vowel between two suffixes, and when I mentioned that, the students thought that made sense. But instead of leaving it at that, we scheduled a Zoom session with our favorite French friend, Old Grouch!

He helped us understand the Latin stem suffix <-i>, the Latin suffix <-um> and the present day English suffix <-ium>! He showed us his own scriptorium and the students decided that a person who does the writing would be called a scriptor. This recognition also lead to a discussion of agent suffixes (those that indicate the noun is a person). That discussion led to a review of using the agent suffix <-or> instead of <-er> if the base can take an <-ion> suffix. The examples Old Grouch used was profession/professor and action/actor. Later, the students added animation/animator, instruction/instructor, and division/divisor! My personal favorite is one that I noticed at an airport I visited in November. The pair is recombulation/recombobulator! If I was in the recombobulation area after going through security, and I was getting all of my things back in order, then I was a recombobulator!

We are so grateful to be able to ask Old Grouch questions. We always walk away smiling, and with a head full of interesting information to ponder! Knowing that we began our Zoom session at 8:20 a.m. and knowing that it was 3:20p.m. where Old Grouch lives, one of the students asked if he had a nice siesta. When he was remarking that he had, he also asked if we knew the word <siesta>. We did not. He explained that it is from Spanish for six. Siesta is held six hours after daybreak! Like I said, we always walk away smiling, and with something interesting to ponder!

Am I correct that the terms “lexical doublets” and “twin bases” are referring to the same thing? Thank you!

Great question, Emily! They are not the same thing. Twin bases are two bases that derived from the four parts of a Latin verb. One of the bases derived from the infinitive form of that verb and one from the supine form of that verb.

An example of twin bases is ‘duct’ and ‘duce’. We see these bases in words like product, seduction, deduce, and produce. These both derive from the same Latin verb. It’s four parts are duco, ducere, duxi, ductum. Once we remove the Latin suffix ‘ere’ off the second part (infinitive), we are left with ‘duc(e)’. Once we remove the Latin suffix ‘um’ off the fourth part (supine), we are left with ‘duct’.

Those Latin stems came into modern English as the bases ‘duce’ and ‘duct’. They are called either twin bases or associated bases.

Lexical doublets are two modern bases that were once one and the same in Latin. The original spelling stayed in use and came into English as it was originally spelled – that is one of the doublets. The same spelling was also adapted by other languages and when it came into English, it now had a different spelling. An example is ‘separate’ and ‘sever.’

Originally, the Latin infinitive was spelled as ‘separare’ meaning “separate, not joined.” You will recognize the Latin stem ‘separ’ that has come into modern English in words like separate and inseparable. This same Latin stem was also adopted by Vulgar Latin and underwent its first spelling change to ‘seper.’ Next it was adopted by Anglo-Norman and the spelling changed to ‘sever’ since that went along with the spelling typically used by the Anglo-Norman. In this way, we ended up with two versions of the same base in modern English – ‘separ’ and ‘sever.’ You can see how they both share the denotation of “separate, not joined.”

Please feel free to email if you’d like further clarification.

Mary Beth

Can’t wait to see your vs. lesson!