Someone asked a really great question in a Facebook group the other day. They specifically wondered why the word ‘chocolate’ didn’t follow the “a_e” rule. In other words, the pronunciation of the last three letters isn’t what is expected. (Just in case you are unfamiliar with this rule, many phonics programs refer to this as the “split vowel magic e rule” or the “split digraph magic e rule”. The underscore represents a consonant. When students see this pattern and the ‘e’ is silent, the ‘a’ will have its long pronunciation.)

The first two people responded with saying that ‘chocolate’ isn’t a word from English, so it won’t follow English conventions. That idea is generally true. Recognizing that a word is not following English spelling conventions is actually a way to spot that a word is probably a loan word. I’m thinking of words like kiwi, ski, khaki, and bikini that have a final ‘i.’ Typically complete English words won’t have an ‘i’ final. They won’t typically have a final ‘u’ either. Examples of words from other languages that don’t follow this English convention are bayou, haiku, tofu, tutu, caribou, and plateau.

While stating that chocolate is a loan word so it won’t follow English spelling rules isn’t false, it won’t help much when a student asks about fortunate, delicate, accurate, or desperate. In my mind, the question broadens to become, “Why aren’t these other words (and perhaps ‘chocolate’ as well) following this rule?” Other people commenting on the post identified words such as I have listed as exceptions. That is unfortunate.

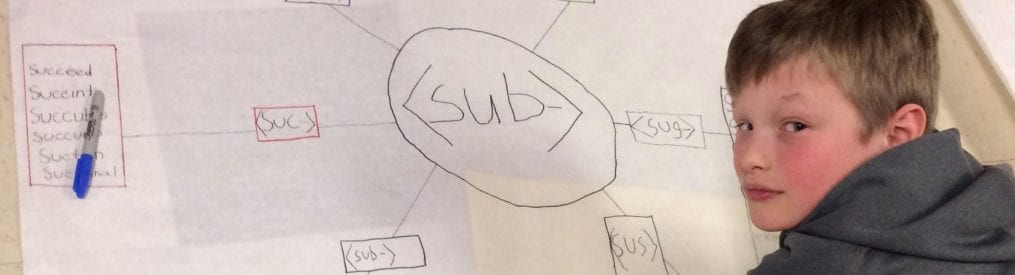

Let’s think for a moment about labeling a word as an exception. What happens then? Nothing. The door shuts on that word. No one tries any further to understand what else might be affecting that word’s ability to follow the rule. (Or to consider that the “rule” might be worthy of critical contemplation.) Students are expected to accept that “exception” is the only understanding they will receive. They will need to remember which words follow the rule and which words are exceptions to that rule.

What I have always taught students is, “Just because I don’t know something about a certain spelling doesn’t mean there isn’t a reason for it.” With that kind of thinking, we are opening the door again on any word that others label as an exception. We are free to think further and collect evidence so we have something to consider. Who knows? We may garner an understanding that will help with remembering a word’s spelling in a way that calling it an exception just doesn’t.

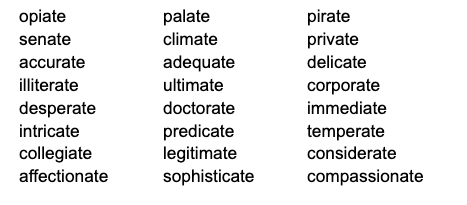

Let’s take a further look at these words considered to be exceptions. I went to Neil Ramsden’s Word Searcher to quickly find words that had the same ending pronunciation as ‘chocolate.’

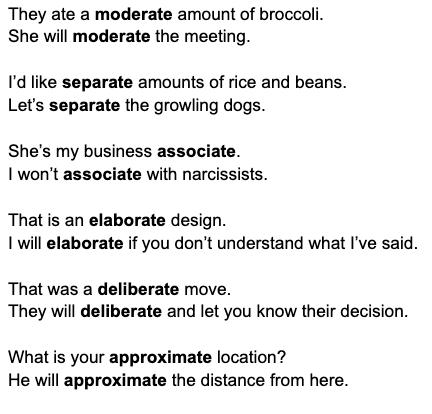

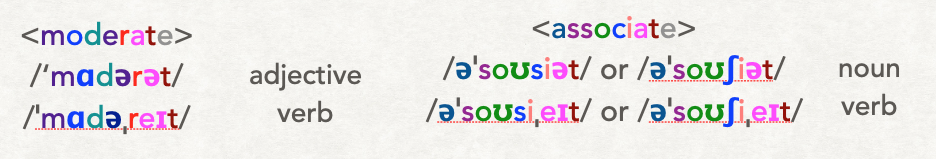

With a list this long, it seems a burden to ask students to remember that these are exceptions to the “a_e” rule. If they don’t remember, and spell the words according to how they pronounce them, they are likely to use ‘it’ or ‘ite’ at the end of each of these words. To add to this, I found words in which the final <ate> can be pronounced in two ways, depending on how the word is used in a sentence. Notice how the pronunciation of the same word changes as it changes its grammatical function (adjective or noun to verb).

Again, this seems like another burden for students who will now be taught that sometimes a word will be an exception and sometimes it will not. There just has to be a more elegant explanation that will truly help our students. What is it that is different in the pronunciation of animate and chocolate? It is the pronunciation of the final ‘ate.’ We’ve known that from the start. But what governs the pronunciation of that final part of the word? Stress. In all of the discussions about spelling “rules” that I see online, very few ever address stress. Stress is one of those things about our language that sets it apart from other languages. It is also one of the things that makes learning our language and speaking it as a native would difficult for many.

Our language is stress timed. If you’re not familiar with that idea (as I wasn’t when I began studying English spelling), you might be wondering what that even means. Simply put, it means that when we speak, we put the main stress or emphasis on one of the syllabic beats in a word. If a word has only one syllabic beat, then that is where we place the stress. Examples of words with one syllabic beat are frog, bed, mask, and light. When you announce those words, you put emphasis on the beginning of the word.

Now consider a word with two syllabic beats such as open, garden, begin, and exposed. Think about where we put the stress when we pronounce those words. Do we say “Open the door,” or do we say, “oPEN the door?” We put the stress on the first beat in that word. It is the same with ‘garden.’ We say GARden instead of garDEN. What about ‘begin?’ With this word, we actually put the main stress on the second syllabic beat. Think about it. Do we say “BEgin your work,” or “beGIN your work?” We put the stress on the second syllabic beat. It is the same with ‘exposed.’ Test it for yourself. Do you say EXposed or exPOSED? My guess is you say it with the stress on the second beat.

In polysyllabic words, one syllabic beat will have the main stress. We may raise our pitch as we announce it and we may hold it longer than we hold other syllables. Sometimes other beats have stress as well – just not has heavy. That is called secondary stress. But the remaining syllabic beats in those words? They are unstressed. And when a syllabic beat is unstressed, the vowel in that particular beat will become reduced to the point that we call it a schwa.

When I have introduced IPA and the idea of stress to my students, I did so by showing them the IPA symbols that correspond to the graphemes in their names, including the stress marks. One year I had boys whose names were Jaydin, Jackson, Aidan, and Kayden. When you say those names, you will notice that you put the main stress on the first syllabic beat of each name. That means that the second syllabic beat of each name is unstressed. With these names, it doesn’t matter which vowel letter we see in front of the final <n>. They are all pronounced the same because they all are unstressed and therefore are reduced in their quality enough to be considered a schwa. When I pointed this out to my students, they thought it was pretty cool. They always wondered why the pronunciation of the second part of their names was the same even though the spelling wasn’t. Here’s a small video clip of two students talking about having learned IPA.

The second student in the video is named Ava. Now that she understands that there is stress on the first syllabic beat in her name, but not on the second, she understands why the two a’s are not pronounced the same! I know that many teachers talk about the schwa sound with students, but I don’t believe that many talk about stress in words or stress in sentences. My guess is that they don’t spend time talking about it because they didn’t learn about it themselves. Because of that, they don’t know quite what to say.

There is a great resource for people who fall into the category of not knowing how to talk about stress seeing as how it was never explicitly taught to them. It’s called Rachel’s English. She has a series of videos that are actually there to help non-native English speakers sound more like native English speakers. One of the things someone learning English probably struggles with is stress – especially if their native language is a syllable timed language like French, Italian, Korean, or Spanish. In those languages, each syllable has the same amount of emphasis. No part of the word or sentence stands out in the same way that they do in English.

When I was first trying to wrap my head around this idea of our language being stress timed, I watched several of these videos. Here is another one that I found to be very helpful.

In the second video, Rachel demonstrates stress with the sentence, “I saw her at the meeting.” When she says it, the primary stress is on the verb ‘saw’ and the secondary stress is on the first syllabic beat of ‘meeting.’ One of the joys of English is that we can change the meaning of a simple sentence like this by changing where we put the stress. I can imagine reading this sentence with the primary stress on ‘I’ and meaning something different than if I put that stress on ‘her.’ The two function words in this sentence (at, the) would probably not carry the primary stress in this sentence very often.

Her next example sentence illustrates that the words in a sentence that are not stressed are reduced. The sentence she uses is, “I got this for you.” It is the function word ‘for’ that is reduced and announced more like ‘frr.’ Can you picture a student who is saying that sentence to themselves as they write it, spelling the word ‘for’ as ‘fer?’ Me too. It makes me wonder about the students I have had who misspelled a word different ways in a single writing. Could it be that the placement of stress in those sentences affected the way the student pronounced the word in that sentence? And if a student is taught to sound out words in order to spell them, they might indeed spell a word one way in one sentence and another way in another sentence.

The next video I’m including is longer than the first two, but continues on with this idea of what we do as we speak. I am fascinated watching these videos of Rachel’s. When we don’t introduce stress to students either at the word level or at the sentence level, we are leaving out such a crucial piece! This kind of discussion could help students understand why they are misspelling some words. It could also lead to a discussion that spelling based solely on pronunciation is prone to error. There are just too many contributing factors. Spelling based on morphemes, on the other hand, leads to spelling accuracy and a built-in understanding of a word’s sense and meaning.

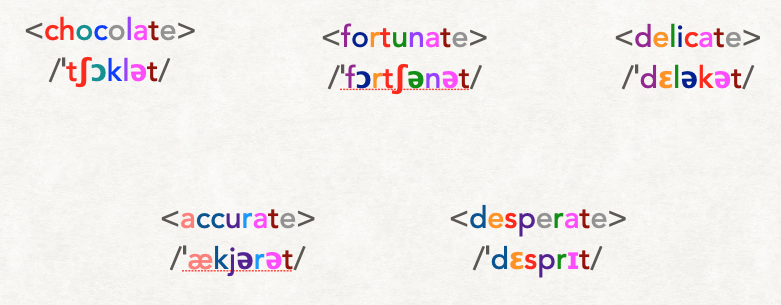

Now that you have a better idea of how inherent stress is to our speech and how important it is to our understanding of spelling, I’d like to return to the words that were mentioned at the beginning of this post. Below I’ve given you the opportunity to compare the graphemes to the phonemes in each word including stress marks. I used toPhonetics to get a spelling to IPA transcription. What do you now notice?

Every one of these words has its primary stress on the very first syllabic beat. That means that the other syllables in each word are unstressed. This explains why the first <e> in ‘delicate’ is representing the phoneme /ɛ/, but the following <i> and <a> graphemes are both representing the phoneme /ə/. The same thing happens in ‘fortunate’, ‘accurate’, and ‘chocolate.’

The words ‘chocolate’ and ‘desperate’ have something else in common. Each looks like it would have three written syllabic beats, but when spoken, there would only be two. Notice the greyed ‘o’ in ‘chocolate’ and the greyed medial ‘e’ in ‘desperate.’ They are greyed because they are not graphemes representing phonemes. Those two particular letters in those particular spellings are so unstressed in the pronunciations of those words that they have been zeroed! The other greyed letters in this collection of words are all the single final non-syllabic ‘e’ that is also not a grapheme. It is there as part of the <ate> suffix. It may mark the pronunciation of the ‘a’ in the suffix when we see it in another member of the word family (desperation), but not necessarily. The <ate> suffix is usually seen on nouns and adjectives whose base derived from Latin. It is the stress placement in the word that determines the pronunciation of the <a> in that suffix.

Above, I gave you examples of words with this <ate> suffix that can be used in two ways. Below I compare the IPA and stress marks on two of those words when the words are used in the two ways.

The difference, as you can see, is that when the word is used as an adjective or noun, there is only one primary stress in the word. That leaves the remaining syllables unstressed and the pronunciation will reflect that by way of reducing the pronunciation of the vowels until they are a schwa. When the same word is functioning as a verb, you can see that the word now has two stress marks. One is primary (ˈ) and one is secondary (ˌ). In both words, there are two syllabic beats that are stressed and one that is not. That unstressed syllable is where we see the schwa.

Reflection

If you are telling your students that sometimes a vowel is pronounced as a schwa, but you’re not telling them why, then you’re not helping them see the logic of English spelling. Without meaning to, you are contributing to the misconception that spelling is weird and hard to understand. How confusing must it be for a student to hear that sometimes vowels are reduced and can all sound similar, but then not to be told when this might happen. This assignment of a schwa must feel very random to a student when in fact it is not. Not at all.

English is a stress-timed language. It is not syllable-timed. Yet, many children are exposed to hours and hours of work with syllables and syllable types and little to no time spent understanding how the stress-timing of our language affects our speech. It is time to recognize the problems created by looking at English spelling with such a superficial lens as pronunciation. It is time to prepare the students for words they are encountering now and the words they will encounter in the future. To do that, we must teach how the English spelling system works. And to do that we must include instruction on morphology, etymology, and phonology (including stress). Trying to explain a spelling without considering stress, morphemes, or etymology is like trying to explain how a plant gets its nutrients by only looking at the surface of a leaf. If you want to understand the system, you have to be aware of all of the components and see how they work together. You can’t peek through the curtain and expect to see the full view. You must open the window and really take in the view.