Something quite amazing and wonderful happened the other day. But before I tell you about it, I need to tell you what led up to it.

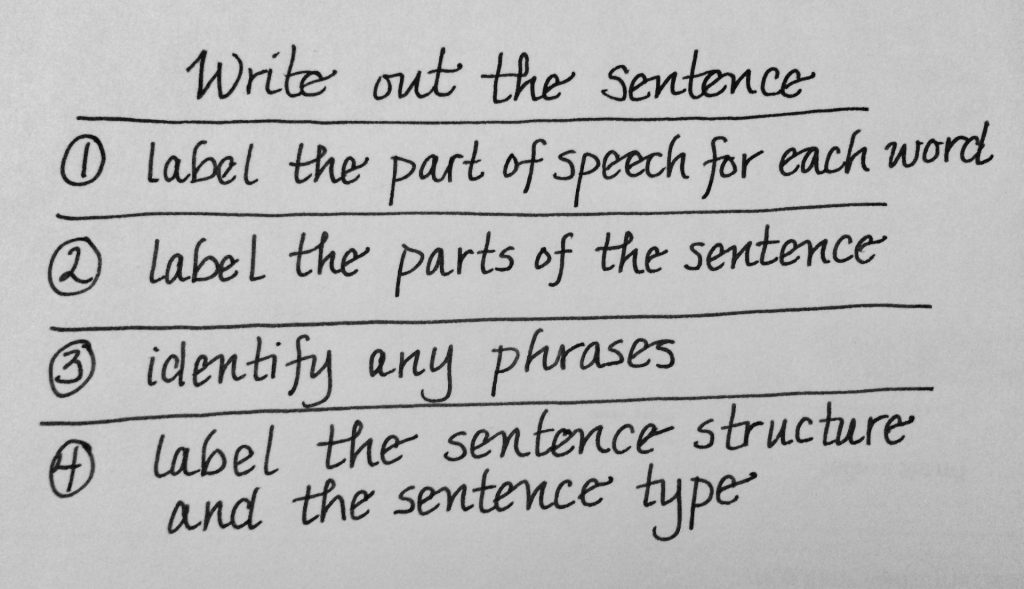

In the past few weeks, students have been working on several orthography projects. Prior to that, they had been working in groups to create podcasts. As each group finished their podcast (based on a word investigation), they needed something new to investigate while the rest of the groups were still working. Instead of assigning the same activity to all who were ready for something, I mixed things up. In that way, when the students are ready to present, we will have a variety of orthographic concepts to be talking about. Here are the projects I assigned:

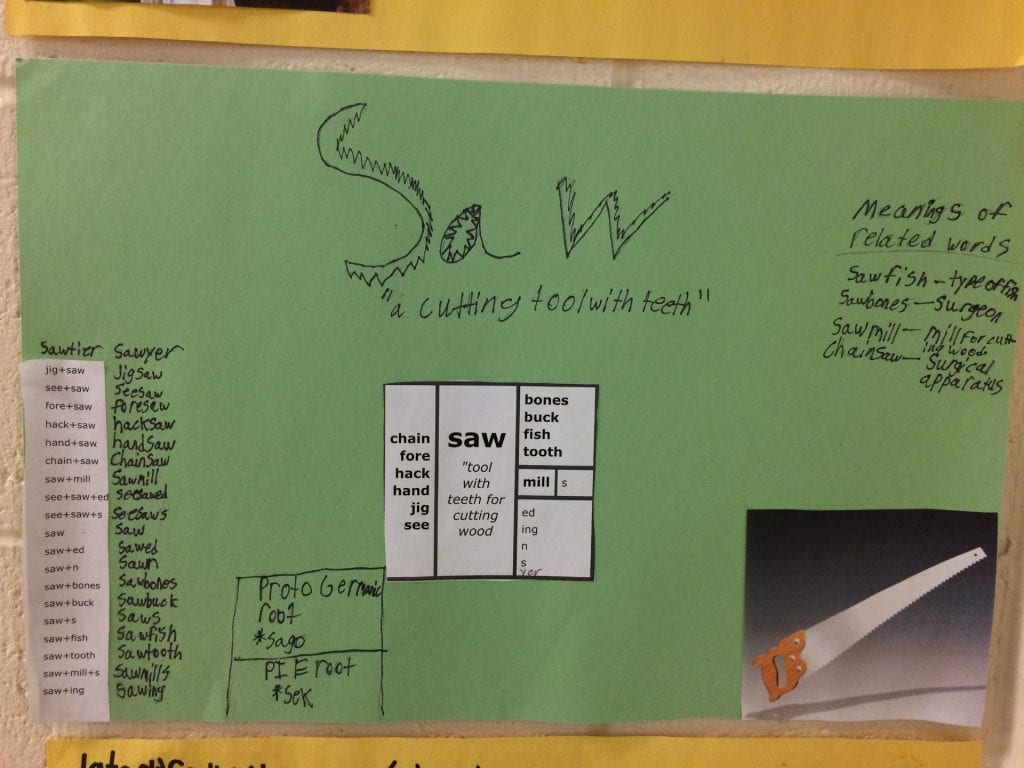

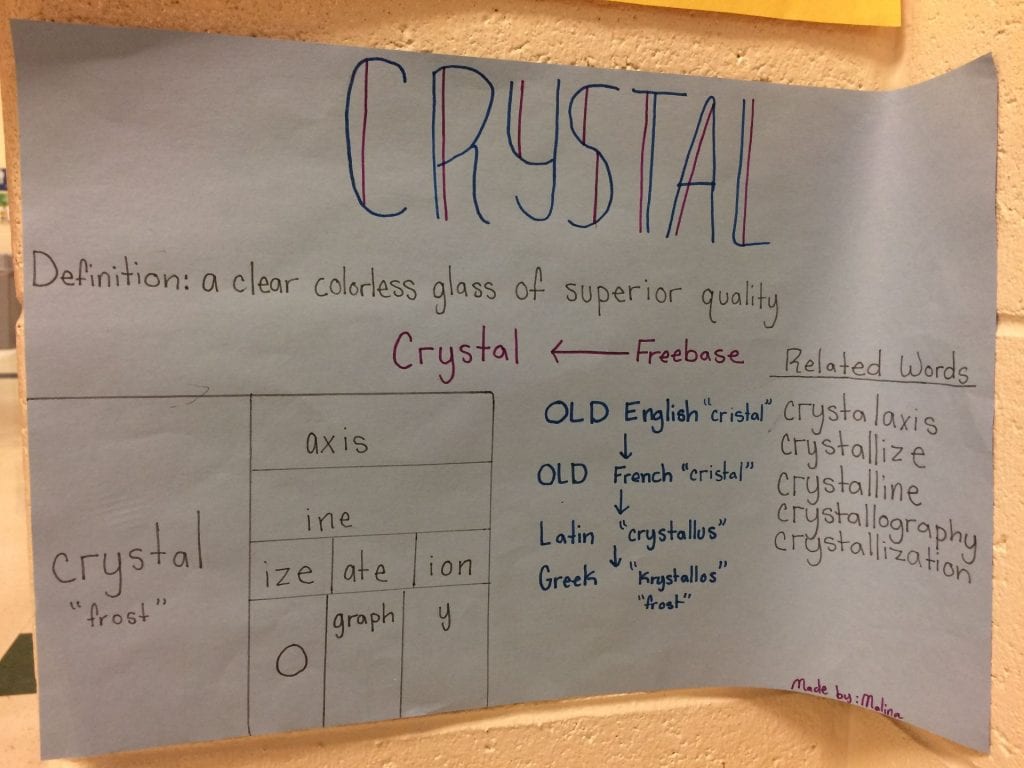

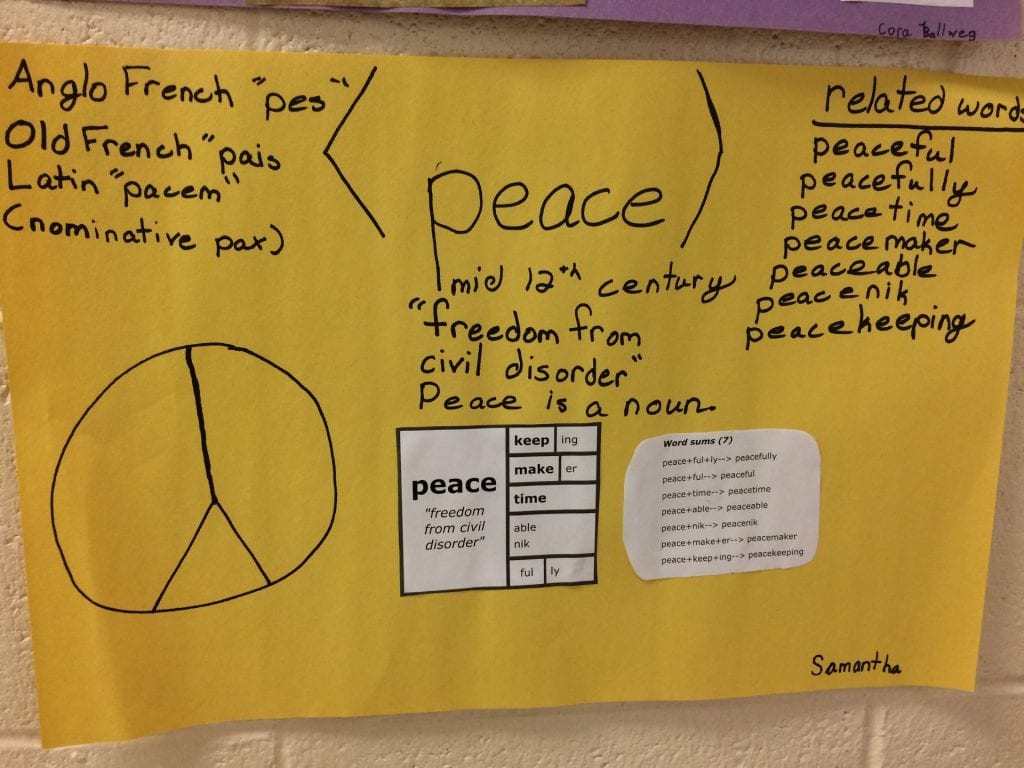

1) I let some students choose a word and independently investigate it. This has become a favorite activity among my students. They enjoy the freedom of choosing their own word and then seeing what they can discover. I like this activity because they get practice using etymological resources (reading and pulling information pertinent to their investigation). They are able to choose whether to use Mini Matrix Maker or create their own matrix. Each finished poster has the same types of information as all the others, yet has been touched by the individual student’s creativity. Here are some examples of finished work:

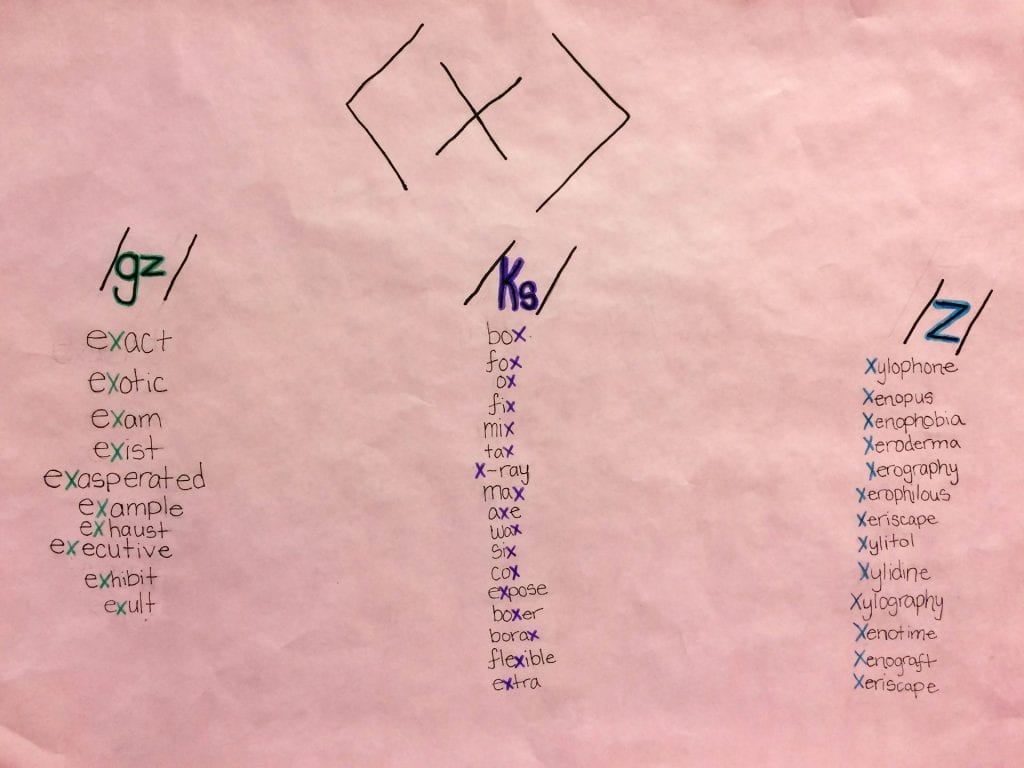

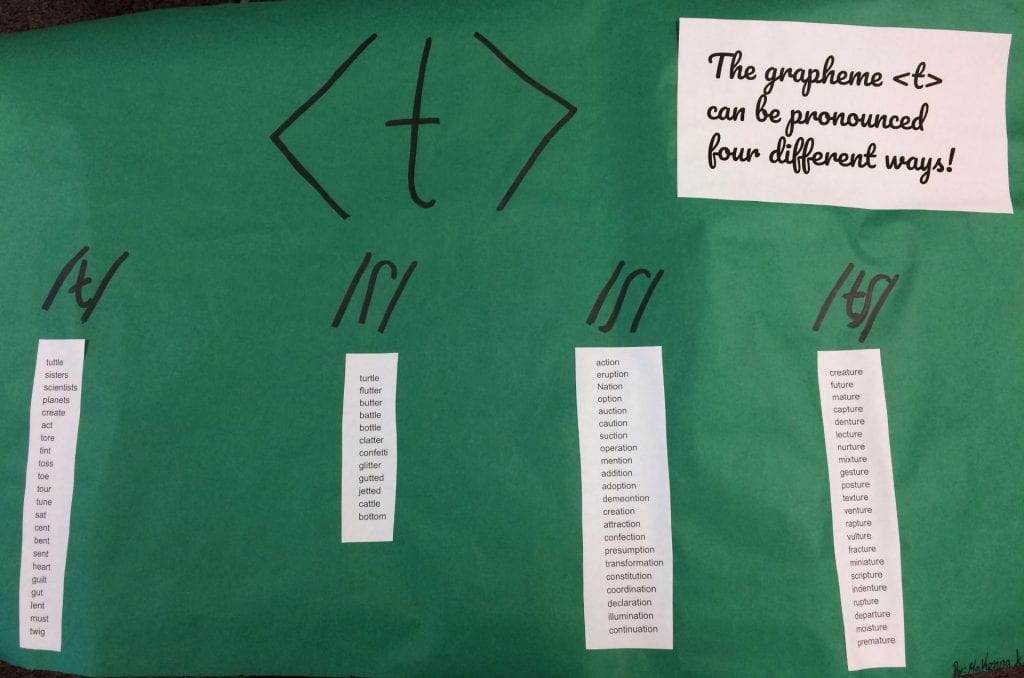

2) Some students were asked to think about an individual grapheme and the phonemes that can be represented by it. They collected words to illustrate that one grapheme can represent several different phonemes. Here are some examples of finished work:

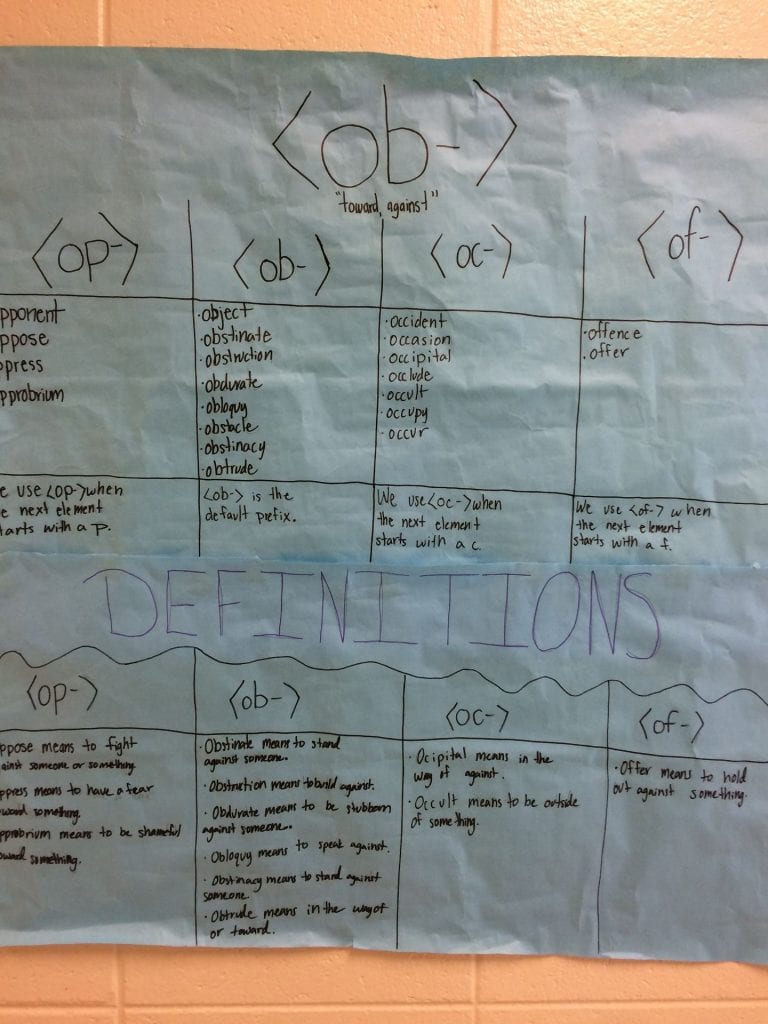

3) Other students were paired up and asked to investigate assimilated prefixes.

I assign a particular prefix to a group. I tell them the assimilated forms I want them to look at. For example, in the picture below, this group looked at <ob->. In addition to words with <ob-> prefix, they collected words that had the assimilated forms <op->, <oc->, and <of->. Before I sent them on their way to find the words, I had them bring a dictionary to my desk so I could show them how to prove that the two initial letters were a prefix and not just the first two letters of a base.

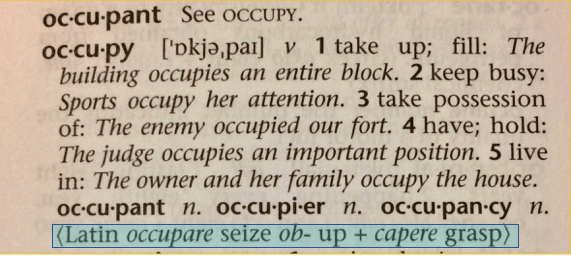

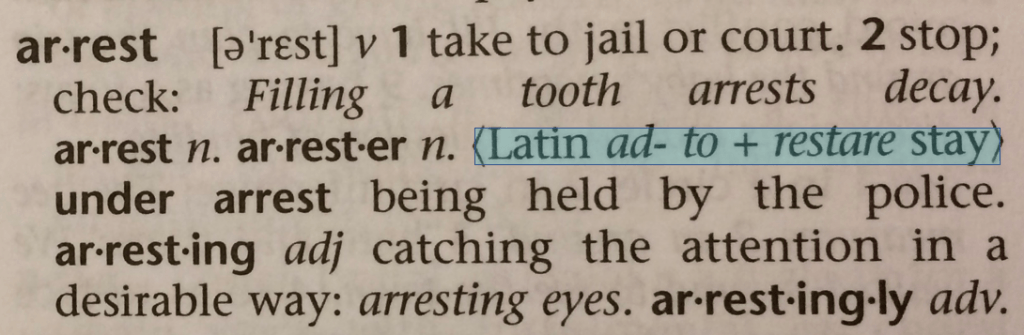

My favorite dictionary for use in the classroom is the Collins Gage Paperback Dictionary. Let’s look at the entry for <occupy>, and I think you’ll see why I like it so much. First of all this dictionary gives the IPA. Not all dictionaries do. Then there are definitions with example sentences. Near the bottom of the entry are related words. And the last thing in the entry is important etymological information. So <occupy> is from Latin occupare “seize”; <ob-> “up” and capere “grasp.” I specifically show the students the prefix listed as <ob->, but that in the word, we see <oc-> because of assimilation having happened.

Once they list words they’ve found in this dictionary, I ask them to use another source as well. My point in doing that is that I don’t want them to rely on any one source as having all the answers. There are interesting things to note when looking at multiple sources, as I’m sure you know. Teaching that aspect of research is important and easy to do here. If the student goes to word searcher next, then they will have to find their evidence of the first two letters actually being a prefix in an etymological reference. We usually use Etymonline. If the student uses the OED (Oxford English Dictionary), the etymological information will be there, although they may end up finding words that are no longer used (which is not necessarily a bad thing as long as they mention its last known use)

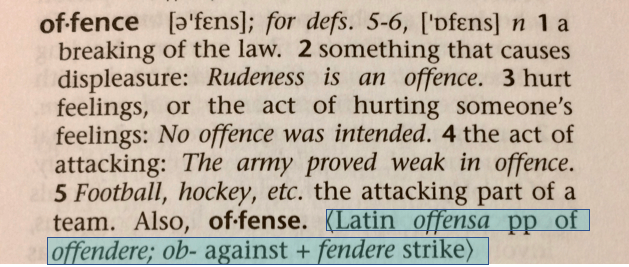

Here’s another example of a word with the assimilated prefix <of->.

What a beautiful opportunity to talk about stress in a word! The two IPA representations show this word two ways. The first is used when the word is defined as in definitions 4 and 5. (It says 5-6, but this must be a typo as there is no 6.) The second is used when the word is defined as in definitions 1, 2, and 3. Where I’ve highlighted, you see that this is from Latin offensa, past participle of offendere; <ob-> “against” and fendere “strike.” Again, we see that in the etymological information the prefix is listed as <ob->, but in the present day word, the assimilated prefix <of-> is used. When the second element in the word begins with an <f>, the <of-> prefix has been used to better match the pronunciation of the first grapheme of the next element.

Two students who had been looking at the assimilated prefix <ad> said that they were ready to present their findings to the class. They had created a poster which they hung on the board. As usual, their classmates pulled chairs close to the front and listened carefully, thinking of questions to ask and word meanings to wonder about.

As they began to share their findings it became more and more obvious that there was a problem. They collected words that began with <an>, <al>, <at>, and <as>, but in the words they collected, those letters were not necessarily prefixes. For example, they had the word <anteater> on their list. A classmate pointed out that it was a compound word, and that if we removed the <an> from <ant>, that would mean that <t> would have to be the base in that word. That didn’t seem likely.

Another word that classmates questioned was <atmosphere>. We studied that word at the beginning of the year and the students remembered that the word sum is <atm + o + sphere –> atmosphere>. Then I spotted <astrologist> and shared that the word sum would be <astr + o + log + ist –> astrologist>. We have come across other words with a structure similar to this (biologist, geologist, hydrologist, seismologist).

There were other words that obviously didn’t have the <ad-> prefix or any of its assimilated prefixes too. The two had identified the <as> in <ashore> and the <ar> in <army>.

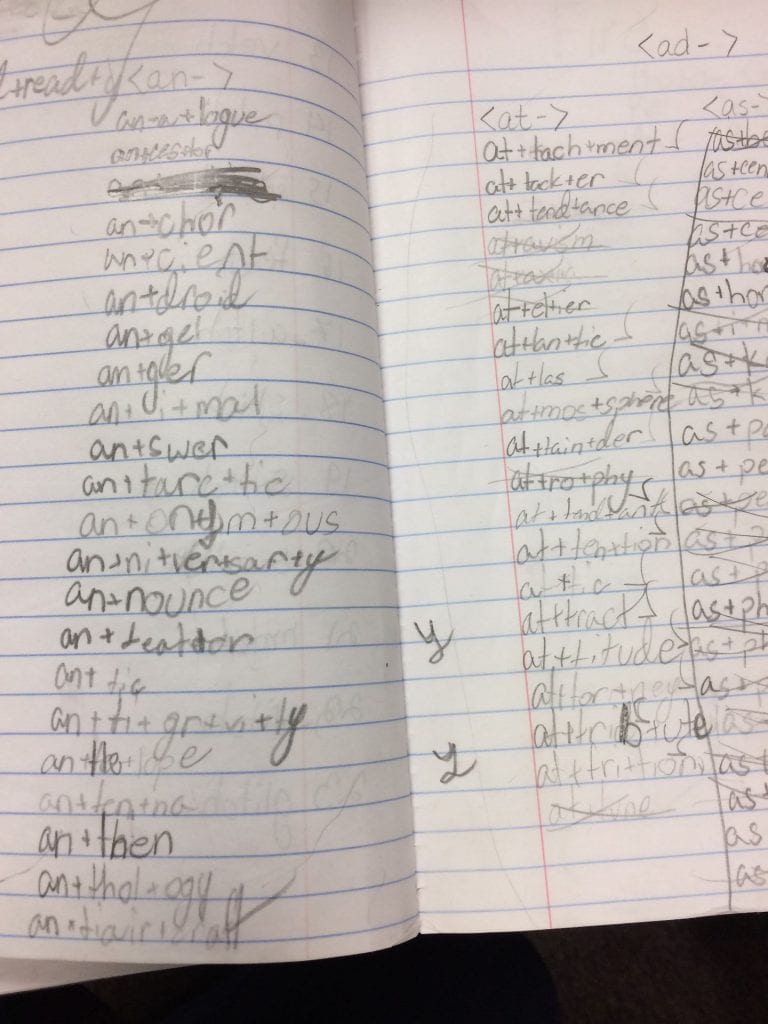

I did not take a picture of their poster, but the next day I took a picture of the notebook they used. You can see that quite a few words on this list look questionable. There are only a few that have an assimilated form of <ad-> as a prefix. For example there is <announce> from <ad>”to” and nuntiare “report”, and <attention> from <ad> “to, toward” and tendere “stretch.” But most of the rest of these have a different story to tell.

The word <android> is from Greek andro- “man” and eides “form, shape.” The word <angel> is from Greek angelos “messenger, one that announces.” The word <anniversary> is from Latin annus “year” and versus “to turn.” Enjoy yourself as you check out some of these others on your own! So back to the presentation and what to do next.

It was obvious that the students must have copied words that began with the same letters as the assimilated forms of <ad-> without checking to make sure that those spellings were indeed a prefix. Even this far into the year, I see that a few of the students still do word work on “automatic pilot.” This activity might have seemed like the word sorts they did in years prior that matched things on the surface of the word without much thought needed. Perhaps they were confused when I explained how to find the evidence and didn’t let me know. Regardless of how it came to be, we were looking at a huge misunderstanding of what a prefix is and what it isn’t!

But my next thought was protecting the inquisitiveness of these two students. They might begin to feel embarrassed if we kept pointing out words that didn’t belong on this list. There sure were a lot. As a class, we have talked often about mistakes being the opportunity to learn something new, but this was a scenario through which I wanted to tread lightly. I wanted to turn this investigation around without my students feeling any shame for having misunderstood the task.

But here’s where the amazing and wonderful thing came in. When I suggested that these two scrap this poster and redo their look at the <ad> prefix, they matter of factly said, “Okay.” They weren’t angry. They didn’t feel defeated. Their body posture didn’t show shame or humiliation. (And believe me, I was watching those two closely.) And because the attitude we’ve spent the year nurturing is one based on proving or disproving our hypotheses based on evidence, these two didn’t feel like quitting either! It was such a deeply satisfying moment. I was pleased, obviously, but also in awe of the environment the students and I have created that allows for failure without judgement. I thought for the rest of the day about this. What contributed to their rather amenable response to being asked to repeat their investigation? When I think back to the beginning of the year, I would have expected eyeballs to roll or mumbling to occur. What was different now? Well, I believe a huge part of the change is the mindset of the entire class. The students (in the audience) who were questioning these words were speaking in a very neutral sincere tone. The presenters didn’t feel judged, and therefore were able to hear what was being questioned and why.

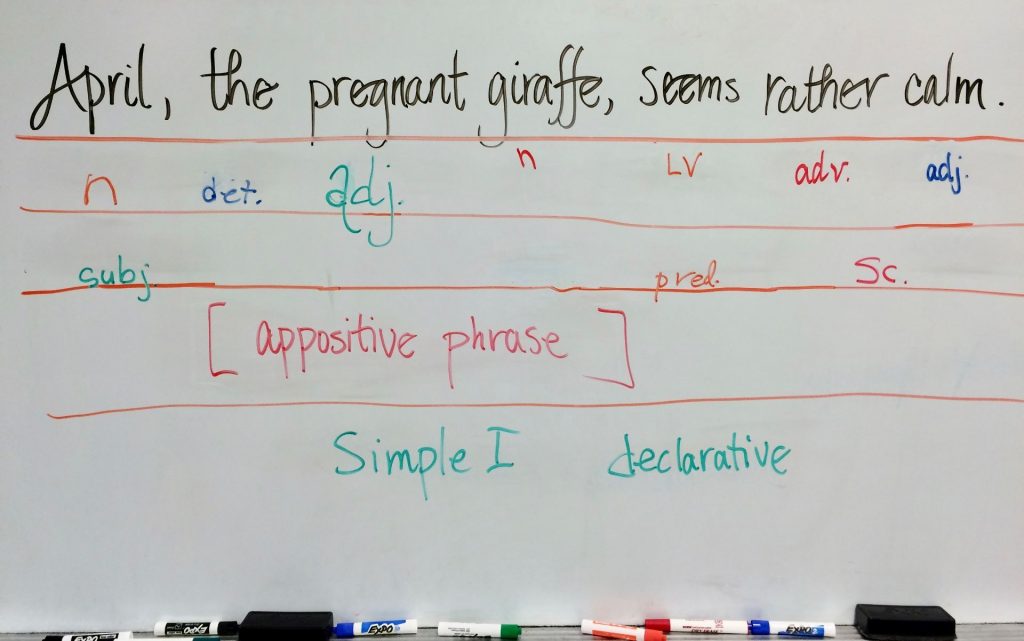

I said to the class, “Maybe it would be a good idea for all of us to review how we know when an initial <ad> is a prefix, versus when it is just part of the word. Can anyone think of a word that might have an <ad> prefix? Let’s walk through the process again. If these two misunderstood how to prove you were looking at a prefix, someone else might be misunderstanding as well.”

A student raised his hand and asked if we could look at<adolescent>. “That’s a great word to look at! I’m not sure what we’ll find about that initial <ad>!”

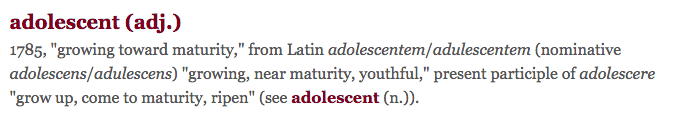

I pulled up Etymonline on the Smartboard so we could all see the entry.

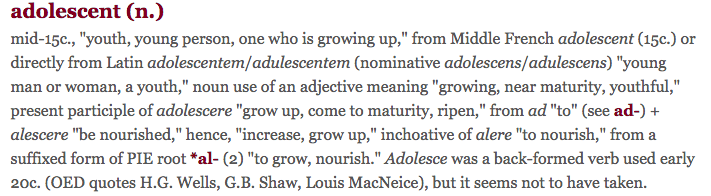

We read through the entry and didn’t feel like the information we were looking for was here. I reminded the students that following the link (dark red) is always a good idea. So we clicked on <adolescent> (n.).

We read through the entry together, discussing the fact that they would be called adolescents because they were young people who were growing up. Then we came to the information we were looking for. This word is from Latin <ad-> “to” and alescere “be nourished” hence, “increase, grow up.”

Next I asked the class if anyone could think of another word with the base we see in <adolescent>. I wasn’t too surprised when no one raised their hand. But it would be important to find one. That would provide the final piece of evidence that in Modern English, we see this base in other words with either a different prefix or none at all. We went to Word Searcher and typed<alesc> in the search bar. We found coalesce, and convalesce. I reminded the students that we had looked at the bound base <vale> “strong” in February and that <convalesce> was one of the related words we found. When someone is convalescing, they are resting and growing stronger. Interesting. There is definitely a sense of “growing healthy” in this word, yet the <ale> spelling can’t be in both the <vale> base and the <alesce> base. I mean it could, but in that moment, I didn’t know. I would be putting that word on my “give this some further thought” list. As I said that, several heads nodded in recognition. Then we looked at <coalesce>. The word <coalesce> means to unite by growing together. It is an assimilated form of <com-> “together” and alescere “be nourished, grow.” Cool! Now we could verify that in the word <adolescent>, the <ad> is a prefix.

At this point the students were ready to have work time. It surprises and delights me that individual work time is one of their favorite things! There are even times (more often than one would guess) when students and I are together in the cafeteria or on the playground, and I am enthusiastically asked, “Do we get to work on our word projects today?”

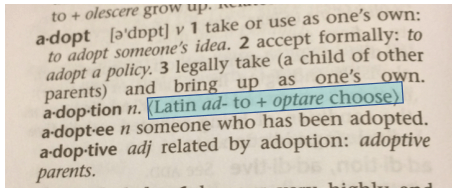

I waited until everyone was busy at whatever task they were involved in. Then I went over to follow up with the group that was redoing their <ad-> investigation. One of the students was still a bit foggy about this investigation. “Go get one of the red dictionaries,” I told him. When he returned, I said, “Open it to the section of words that begin with <ad>.” I wanted to make sure these students were on the right track. We came across the word <adopt>. I had one of them read the entry out loud. As we discussed this word, one of the students knew that babies could be adopted, but hadn’t really thought about ideas being adopted. Then we came to the evidence we were looking for. I have it highlighted for you. I said, “Look at that! The prefix has a sense of “to” and the base has a denotation of “choose!” Does that make sense with what we understand this word to mean?” They both agreed that it did.

Now I wanted to show them what they would find with one of the assimilated forms of <ad->. I asked them to turn to the <ar> section. As we read words on the page, we were looking specifically for the last line of each entry. Then we spotted the words <Latin ad- “to” + restare “stop”>. Our eyes went back to the header word which was <arrest>. One of the students read the definition. It was surprising to the students that arrest could mean stop as in the sentence, “Filling a tooth arrests decay.” When we read the highlighted portion after having read the rest of the entry, it made sense. To stop something is to make it stay.

At this point, I asked if they understood better what to be looking for. They said they did and promised to call me over if they had any questions. It was time to let them at it!

I made my way around the room checking in on other groups/individuals. There were at least two groups that had completed a look at assimilated prefixes and were ready for another new investigation. I called them over to my desk and gave them a mini lesson on Latin verbs. We have talked about Latin verbs as a class, and now it was time for the students to investigate on their own. I gave each group of two (and in some cases a student on their own) a card with the four principal parts of a specific Latin verb. I will explain this process further in another blog post.

As I was talking to one group about Latin verbs, I saw the group that was redoing their work on assimilated prefixes raise their hands. I went over as soon as I could. “How’s it going? Are you finding words you have questions about?”

And then the boy (who is not generally excited about classroom stuff) enthusiastically said, “Yes! Did you know that <journ> means “day?”

My first response was, “Yes, I did know that. We see it in journal, right?”

“Wait. What? In journal? How does that mean day?”

“Well, generally, how often does a person write in their journal?”

“Oh! Every day! Cool!”

“And what about a journey?”

“A journey? That’s like going on a trip.”

“Right. And your journey is measured in days.”

“That is so cool!”

And that’s when the bell rang and it was time to clean up and leave for the day. Here’s the really funny thing. These two that were enthusiastic about <journ> were the two who were working on the <ad-> prefix. I walked away wondering how in the world they came across <journ> in their search for assimilated forms of <ad->. But just now it seems so obvious. You probably already put two and two together, didn’t you? Or should I say <ad-> and <journ>. Too funny. I’ll have to make sure I adjourn the class tomorrow instead of dismissing them. I’d love to see their eyes light up with recognition!

SWI provides a reliable framework for our investigations and guides our thinking. Questioning becomes an expected activity and instead of being intimidated by someone questioning your work, you become interested, truly interested in what it is they question and whether or not you’ve misunderstood something. Individually, the goal is always to understand things better. In order to stay focused on that goal, you need to hear the questions and give them consideration. Too often we hear a question, take it as a criticism, and then defend our position, right or wrong. We’re not really considering the question. Instead we are plotting our defense. Structured Word Inquiry has brought a culture of listening and questioning to my classroom. The words “right” and “wrong” have been replaced with “proven” and “could be, but I’m not sure about that.” That culture has made my room a safe place for learning. A place for true scholarship. It is an exciting place to be every single day!