Knowing my students would love a little Halloween fun, I ordered some special vampire slime from Steve Spangler Science supplies. But before I revealed what we would be doing, I wrote the following words on the board and asked if either looked familiar to anyone. It got pretty quiet for a moment until a few hands went up with claims of, “I’ve heard the word ‘polymer’, but I don’t know where I’ve heard it or what it is.”

“Perfect!” I said.

Next I asked the students if they noticed anything similar about these two words.

“They both have <er> at the end, and <er> is a suffix”.

“Great observation! Oftentimes an <er> is a suffix. We’ll see if that’s what’s happening here!”

“They both have an <mer> at the end”.

“Very interesting! That is true.”

“They both have <o> as their second letter”.

“They DO! How interesting. I wonder if that’s important or if it’s just a coincidence.”

“Is the <y> in ‘polymer’ a vowel? Because if it is, every other letter is a vowel in both of these words.”

I thought that last questions was great. After all, these two words were totally unfamiliar to the students. After a quick discussion about when <y> is a consonant (yellow, yolk, yard) and when it is a vowel, the students decided it was a vowel in this word. It didn’t matter whether I pronounced the word as /ˈpɑləmɚ/ or /’pɑlimɚ/.

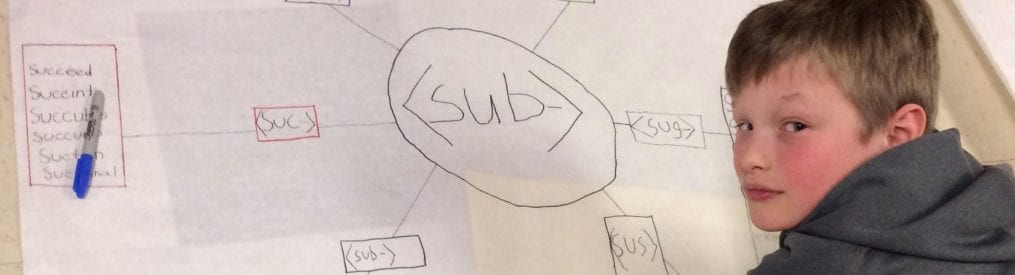

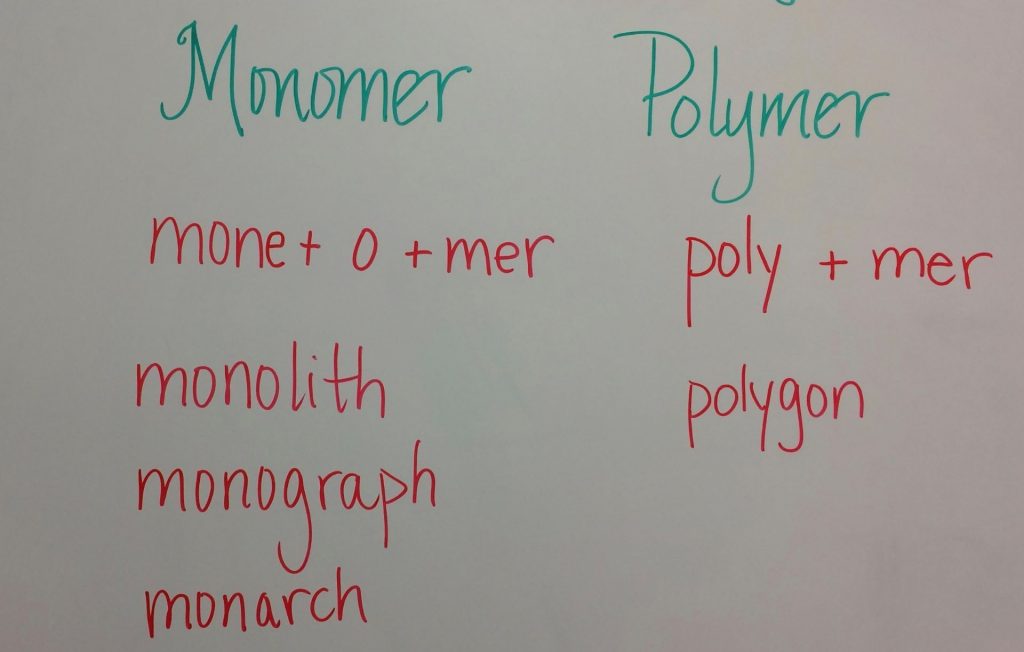

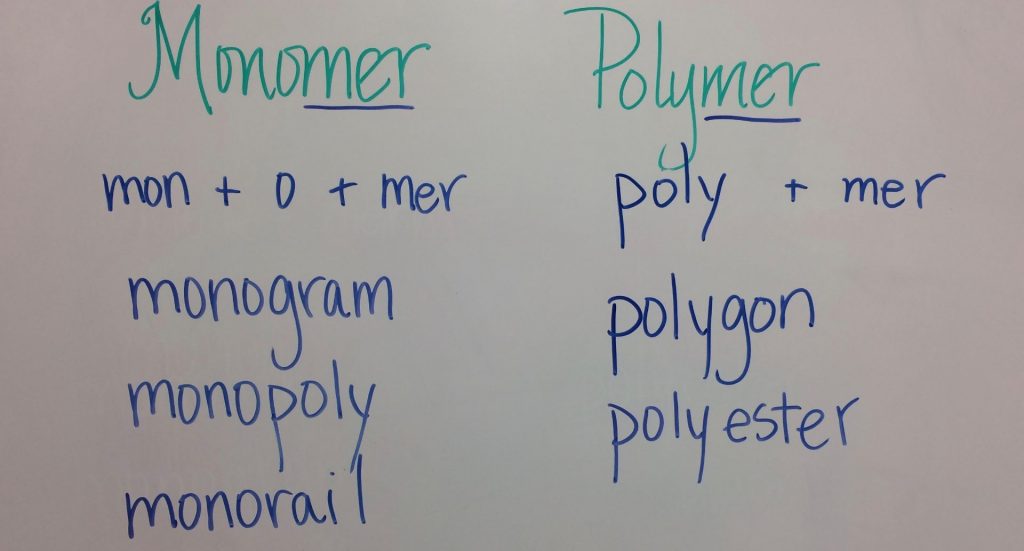

Back to the list of observations. After I repeated the observations made by students, I asked if anyone was ready to make a word sum hypothesis for one or both of these words. The very first student I called on suggested <mon + o + mer –> monomer> and <poly + mer –> polymer>. I was curious to see what others would think about these. But the majority agreed and named the <o> as a connecting vowel. I said, “If the <o> is a connecting vowel, one or both of these morphemes will need to be from Greek, right?”

At this point I asked if anyone knew offhand of some words that might have <mon> or <poly> as part of them.

Great! This gave us evidence that we might be on the right track. Now we needed to look at Etymonline. First I looked at ‘monomer’.

We found out that it was first attested in 1914. The first part is from Greek monos “one”, and the second part is from Greek meros “part”. When I looked at ‘polymer’, we found out it was first attested in 1855. the first part is from Greek polys “many”, and the second part is from Greek meros “part”. Several of the students remembered that we have seen the Greek suffix <os> on other Greek roots (thermos, lithos, hydros, tropos, cosmos, etc.). So we removed it to find the base element that has come into Modern English.

We also talked about a potential <e> on the base <mone>. We saw that it has a single final consonant with a single vowel in front of it. If we don’t consider placing the potential <e> there, we would expect the <n> to double in the word monomer or monolith. The final non-syllabic <e> would prevent that doubling. So we chose to include it.

So from our look at Etymonline we had evidence that each of these two words shared the same base element of <mer> “part”. From there we could safely say that a monomer had to do with one part and a polymer had to do with many parts. We briefly talked about our brainstormed words (I knew I would review them a bit more leisurely the next day).

It was time to relate these two words to the science lesson. I told them to picture themselves as a molecule – a particular combination of atoms. And everyone in the class was the same kind of molecule. I could refer to each one as a monomer.

If I asked several students to get up and form a conga line and move around the room, each monomer would join with another of its kind and create a chain. I could then call the chain of monomers a polymer. A polymer is many of the same monomers joined together. And because they are joined together, they behave differently than monomers on their own.

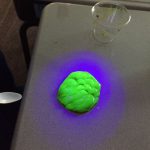

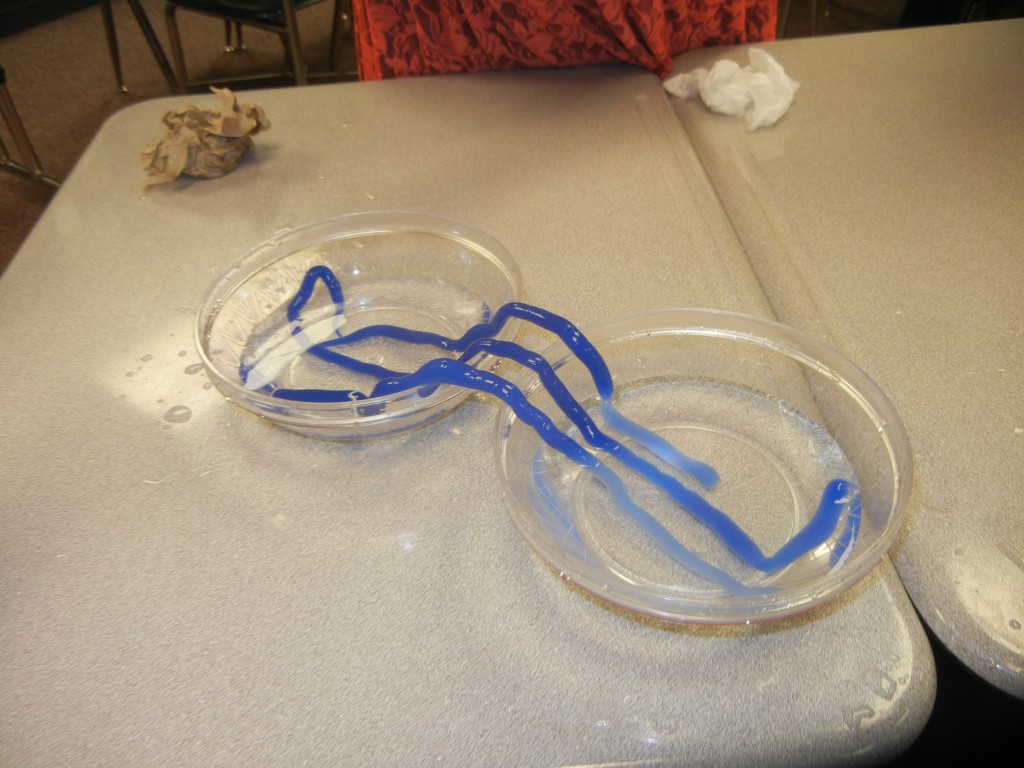

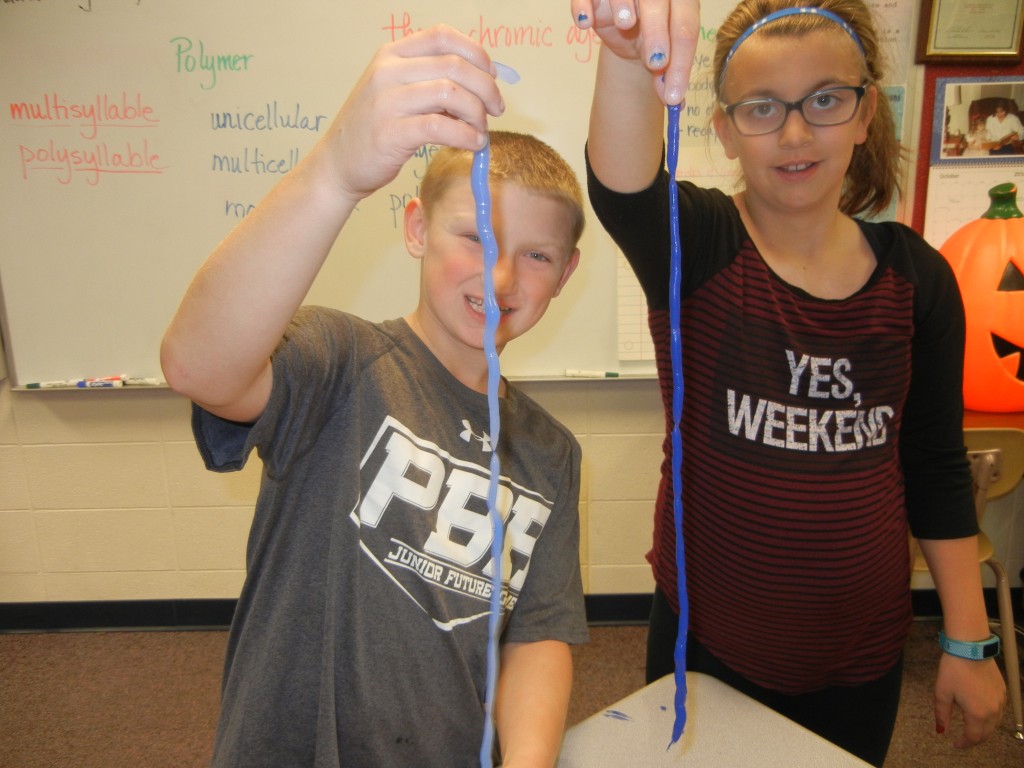

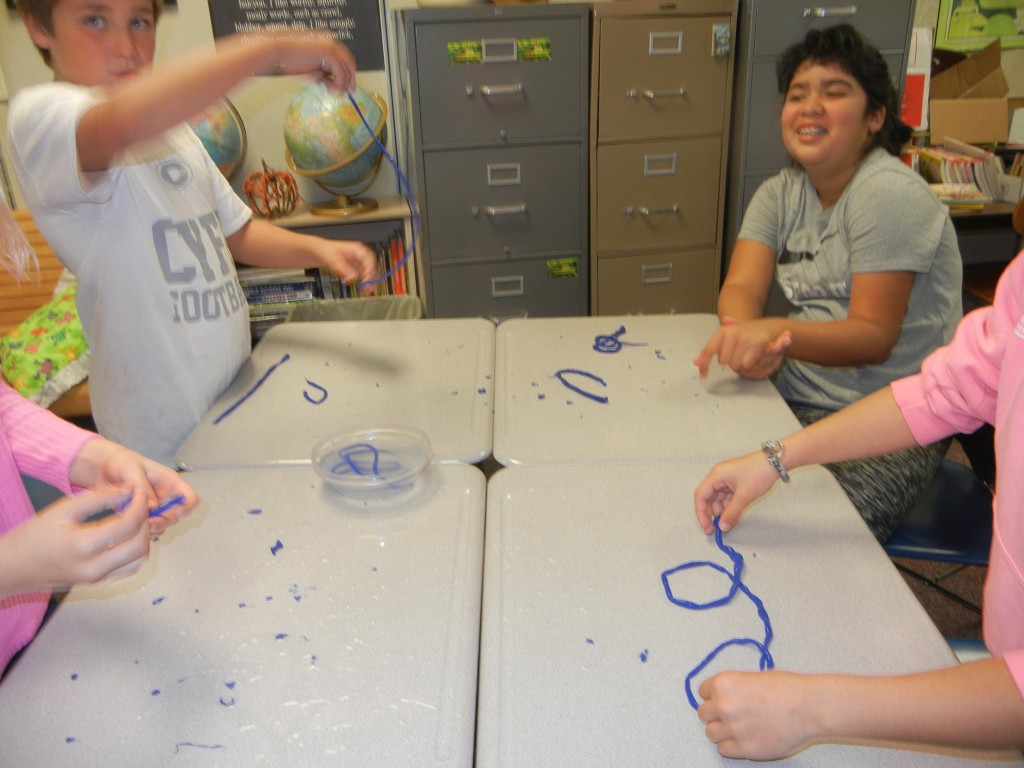

Time for slime

Each student got a cup with special green goo in it. As soon as I measured in the second ingredient, they mixed until the slime was ready to play with. This was really cool slime! When it was held up to the light, it was red. When it was on your desk or in your hand, it was dark green. When held up to a black light it was yellowy-green. If you pulled to quickly, it broke in pieces. But if you left it sit in your hand, it slowly oozed out and leaked slowly over the edge of your palm. When stretched thin it was translucent. When balled up, it bounced and jiggled. So cool!

When we were done playing and cleaning up, we talked about the slime and the way the polymers behaved. The slime sometimes felt like a solid, but then at other times it felt like a liquid. And I reminded them that the slime was really chains of monomers – all the same kind. I asked them if washing their hands under running water felt the same way as handling the slime. When they said no, I told them it was because the molecules of water were freely moving – not in chains like the slime.

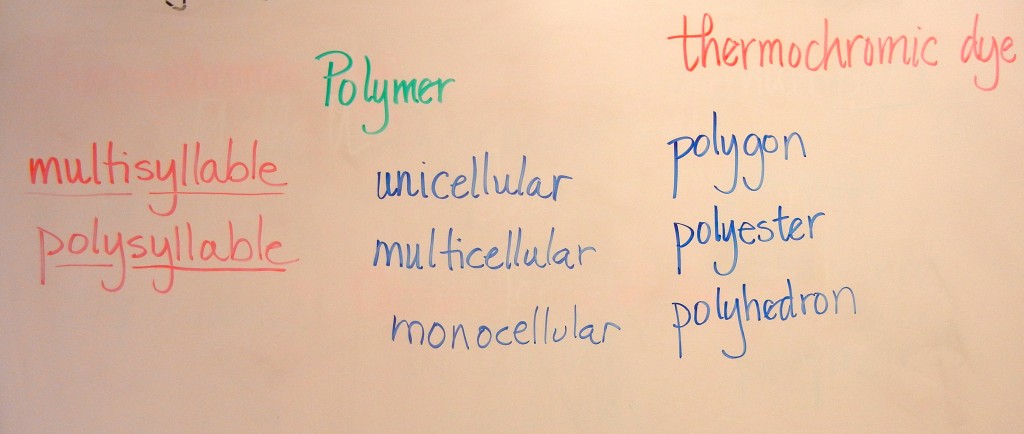

Day Two: I wanted to review the words monomer and polymer. They were still on the board along with their word sums. I even added a few words I thought of.

From there we talked about each of the suggested words and what the relationship would be with either <mon> “one” or <poly> “many”.

The lists shown above vary because I have three groups of fifth graders each day. Each group, naturally, thought of different words. Between making guesses based on what we now knew and using the dictionary, we found the following:

A polygon is a geometric shape with many angles.

Polyester is a fabric made with fibers containing polymers.

A polyhedron is a geometric shape with many faces.

A polyglot is a person who knows many languages.

A monologue is one person delivering a message to an audience.

A monarch is one person who rules a country.

A monocle is a single lens eyeglass.

A monolith is one very large rock or stone.

A monograph is writing on a single subject, usually by a single author.

A monogram is the joining of two or more letters to form one symbol.

A monorail is a train running on a single track or rail.

Lastly we came to monopoly. It didn’t take long before someone noticed that this word had both <mon(e)> and <poly> in it! A monopoly is exclusive control over a commodity. We talked about the monopoly on tea during the American Civil War to have a real life example of what this meant. We could see that exclusive control would be by one person or one company. But we were a bit confused by the <poly> “many”. Did that refer to the people? We went back to Etymonline to see what we could find about this word. WOW!

For a minute there, we got caught up in WYSIWIGERY! That just means “What you see is what you get”. Just because two things look alike, it doesn’t mean they are! It turns out that the <poly> in monopoly is from Greek polein “to sell”. That makes much more sense when we think about what a monopoly is!

But the very best thing happened next. A boy raised his hand and asked, “We have the word ‘monorail’. Why isn’t it ‘unirail’? Doesn’t <uni> also mean one? What a truly brilliant question! I asked the class, “Is this true? Do words with <uni> have something to do with one?” There were lots of hands raised. The words unicorn, unicycle, unit, universe, united, unison, and unique were suggested as proof.

“Okay. Then let’s go back to Arshenyo’s question. Why do both <mon(e)> and <uni> exist if they mean the same thing? Why do we have two different base elements for the same thing?”

The first thought offered was that we need monorail because unirail sounds so weird. But then we agreed that perhaps it sounded weird because we’ve never said it before. Could there be something else? And then the very next thought expressed by the very next student (and this happened in all three classes) was, “Maybe it’s because one is from Greek and the other is from Latin.” Calmly and brilliantly, my students are becoming scholars!

Hours later as I write this, I’m still smiling!