Our school year has ended. Nobody is going to deny the unusual circumstances that we were all thrown into during the last ten weeks of our school year! In fact I can never remember a single situation affecting schooling worldwide like this pandemic has! Teachers and students the world over scrambled for weeks trying to see if any teaching style could match the face to face teaching/learning we are all so used to. But that burden is done for my school district. Our school year is over. Our rooms are ready for summer cleaning, and our fifth grade students are ready to move on to the middle school in the fall. In the midst of what has not at all felt normal, those simple acts of getting our rooms ready for cleaning and our students ready for the next grade have brought us back to the routine we expect at this time of year.

But there has been one more big change in my building. Six of my colleagues have retired. SIX! If you work in a large district, that probably seems like a pittance. You probably lose many more than that to retirement each year. But in my world, we don’t. I have worked in the same district and at the same grade level for 26 years. I know each of the six retirees personally. One of them I knew as a parent when both of our children were in second grade together. Another of them was our children’s second grade teacher. One is married to a former pastor of my church down the street from our school. One has been my 5th grade colleague for all of my 26 years. Only two of the six began working at our school after me. So you can see just how unique this retirement situation is, and how odd it will feel to begin a new school year without the personalities that have brought joy and camaraderie for so many years.

I often speak of the staff at our school as one of our strongest assets, and because these six people have been so special, I spent a lot of time thinking of what their retirement means to me. And then (if you know me at all, you know where this is going), I began to wonder what the word ‘retirement’ means to anyone. What is its story? As a kid I used to think it meant that someone was tired of doing their job, so they stopped doing it. Is it really as simple as that?

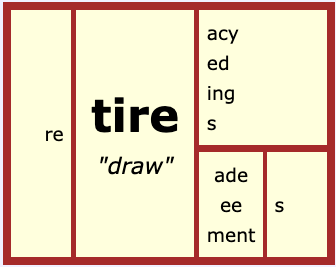

Starting at Etymonline with the word ‘retire,’ I found that this word was first attested in the 1530’s. At that time it was something armies did. It meant “to retreat.” It was borrowed from the earlier Middle French word retirer “to withdraw.” The <re-> had a sense of “back” and the <tirer> had a sense of “draw.” Looking at the Oxford English Dictionary, We get a better idea of how this word was used in French.

- Middle French, French retirer to pull or draw (something) back (12th cent. in Old French),

- to remove, withdraw (something from someone) (13th cent.),

- to remove (someone from a particular place or position),

- to free (someone from captivity),

- to keep (something) in reserve,

- to deter or turn (someone) aside (from a vice, etc.) (all 15th cent.),

- also (reflexive) to withdraw, go away (end of the 14th cent.),

- to go off to somewhere peaceful or secluded,

- to withdraw somewhere for protection,

- (in military context) to retreat (all 15th cent.),

- (reflexive, of the sea) to ebb (c1500),

- (reflexive with de ) to give up (a habit, etc.) (1508),

- (reflexive with de ) to cease to perform or pursue (a specified activity, mode of employment, post, etc.) (1538),

- (reflexive with de ) to cease to frequent (someone) (1553)

The OED goes on to say, “French retirer shows a number of senses not paralleled in English, especially senses related to the core meanings ‘to take back, take away, remove’. In modern French the meanings ‘to leave employment’ and ‘to withdraw (something) from service’ are usually expressed by constructions with retraite (retreat), rather than with retirer.” Isn’t that last bit interesting? What we in English speaking countries refer to as retiring, the French refer to as retreating. What is extra interesting is that both of those words come to us from French!

Checking with my Chambers Dictionary of Etymology, I find that ‘retreat’ is first attested (in English) in about 1300 and was a signal for a military withdrawal. It was borrowed from Old French retret, retrait, and is from Latin retrahere “draw back.” Since it can be traced back to Latin, it is an older word than ‘retire.’ As I mentioned above, ‘retire’ was first attested in the 1530’s.

Heading back into Etymonline, I find that it wasn’t until the 1640’s that this word was applied to a person withdrawing from an occupation. Interesting. Retiring from a job simply meant to withdraw from that job. The sense and meaning hasn’t changed! But it has broadened. By the 1660’s, it was also used to mean “to leave company and go to bed.” Every once in a while I come across this use in a story. Perhaps you have too. Someone might say, “I’m feeling tired. I’m going to retire for the night.” As we’ve found out earlier, as this word was associated with the military, it meant “withdraw, lead back,” but by the 1680’s it also meant “to remove from active service”. That is a very similar sense to retire from one’s occupation, isn’t it? The final sense listed at Etymonline is from 1874, and it is the baseball sense of “to put out.” So to retire the runner, could mean you threw the runner out at the base.

Two words that I found while making this matrix fascinated me. The first is ‘retiracy.’ I’ve never heard of it that I can remember. Etymonline describes it as modeled on ‘piracy’ in 1824 American English. Sounds like humans playing around with their language again! I can’t wait to wish my friends fun in their retiracy!

The second fascinating word on this matrix, and the only word here that does not have anything to do with leaving a job, is ‘tirade.’ When I think of a tirade, I think of a long, often angry speech, or perhaps two people bickering back and forth. The interaction is drawn out, hence the base <tire>!

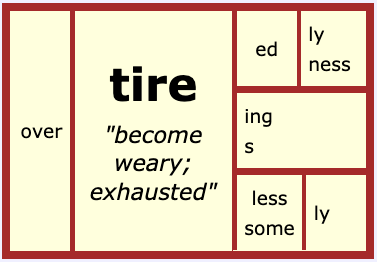

Have you noticed that so far there’s been no mention of being fatigued, exhausted, or tired? So if the base of ‘retire’ does not have the same base we see in ‘tired,’ then what’s the story of <tired>?

credit to marfis 75 on flicker

Combining what I found in Chambers and at Etymonline, I read that before 1460, this word was spelled tyren. It was developed from Old English tēorian at about 1000 and in Kentish tiorian before 800. It was used to mean “to fail, cease; become weary; make weary, exhaust.” The fact that the <tire> in ‘retirement’ and the <tire> in ‘tiresome’ come from completely different languages gives us evidence that they are not related etymologically, and most certainly won’t be related morphologically. They are two completely different words!

Even though most people wouldn’t consider the kind of tire we see on our cars to be confused with either of these other bases, I’d still like to address it. After all, it is another base that has this same spelling of <tire>. If you’ve never looked up this word, you are in for a treat!

This word dates back to 1485 and was used to mean a band around a wheel. At that time it was spelled <tyre> and meant the iron rim of a carriage wheel. What’s fascinating is that it is a shortened form of the word ‘attire.’ The prefix is an assimilated form of <ad-> “to” and the base is <tire> “equipment, dress, covering.” According to Etymonline, “The notion is of the tire as the dressing of the wheel.” My Chambers Dictionary gives further information indicating that the band of rubber on the rim of the wheel was first recorded in 1877. It was first used on bicycles before being used on cars. I’m sure the iron lengthened the life of a carriage wheel before then, but I can’t imagine what kind of a bumpy ride it provided! And it’s obvious that improvements have been made on the rubber tire ever since! Another fascinating thing about this word is its spelling. When it first appeared, it was spelled <tyre>. From the 1600’s through the 1700’s, the standard spelling was <tire>. But then at the beginning of the 1800’s, the British revived the spelling of <tyre> which still remains standard in Britain while in the United States, the spelling remains <tire>.

While we’re on the subject of tires (as in the covering on a wheel) I found an interesting bit on the word ‘tire-iron.’ Originally this was one of the iron plates off of the older fashioned wheels and was used to pry the tire off the wheel. The name ‘tire-iron’ caught on in 1909. We still call the tool we use to pry a wheel off of the rim a tire-iron, and now you know why.

Before I retire this topic …

Did you recognize the title of this post? It is a line from A Christmas Carol by Charles Dickens. In the passage, he has just had an exchange with his nephew and is reflecting on how silly it is to celebrate Christmas when you haven’t any money. It is the last line in the following excerpt:

“There’s another fellow,” muttered Scrooge, who overheard him: “my clerk, with fifteen shillings a week, and a wife and family, talking about a merry Christmas. I’ll retire to Bedlam.”

So now that you know more about the word ‘retire,’ you can understand that Scrooge means to withdraw from this conversation and head straight for the insane asylum in London, (St. Mary of Bethlehem Hospital, which was commonly referred to as Bedlam at the time). He can’t understand how people with very little money can be so full of joy, while he who has more than he needs, is miserable. He sees this disconnect as him being surrounded by insanity. His pursuit of wealth doesn’t just cloud his thinking, it blocks him from pursuing human relationships, where real happiness lies. I find it remarkable that a look at a word I kind of had a sense about, in a passage I’ve heard many times, suddenly creates a sharper focus on the meaning of that word. In turn, the deeper understanding of the word shines a brighter light on the overall meaning of the passage, as if being viewed from a wider lens.

Perhaps people associated retired with having something to do with being weary or fatigued, because generally the people who choose to retire are older. As of November 2019, the most common age for retirement in the U.S. was 62. Those people have worked at their jobs for many years and it is not a stretch to imagine they might be tired of it or tired because of it. And that may certainly be the case for some. But if we look at the words and understand what they mean, we can better understand how to use them! We can get an orthographical kick out of the fact that we have three bases, all spelled exactly the same (<tire>), but deriving from three different ancestors and with three distinct meanings! Some of those who are beginning to see the value in teaching children about morphology are still wagging about teaching them etymology. Yet here’s evidence that etymology can hold the key to an understanding that neither morphology nor pronunciation can provide on their own. That’s why we must teach students to look at all three.

As a farewell to my colleagues I wrote up a shortened form of this post and gave it to each. I closed with a quote from the Century Dictionary that I particularly love.

“Retirement is comparative solitude, produced by retiring, voluntarily or otherwise, from contact which one has had with others.”

I think of my colleagues, my friends, as withdrawing from employment at our school and enjoying comparative solitude. They will leave the “noise” of education behind and take with them every laugh between friends, every tender moment, and every triumphant teaching joy. They will immerse themselves in comparative solitude. I couldn’t wish for anything better than that! Congratulations, my dear friends!