It’s all well and good that we can put on an extra layer when the wind gets chilly and the temperatures drop, but what do the wild animals do? How do they cope with the heavy snow and freezing temperatures? That is the focus of the article I read recently. It’s called “Do Wild Animals Hate Being Cold in Winter?” It was published in Popular Science, written by Bridgette B. Baker. You can read it at THIS LINK.

As I read it, I couldn’t help but notice a number of words that share the base <therm>.

“In fact, wildlife can succumb to frostbite and hypothermia, just like people and pets.”

“One winter challenge for warm-blooded animals, or endotherms, as they’re scientifically known, is to maintain their internal body temperature in cold conditions. Interestingly though, temperature-sensing thresholds can vary depending on physiology. For instance, a cold-blooded—that is, ectothermic—frog will sense cold starting at a lower temperature compared to a mouse. Recent research shows that hibernating mammals, like the thirteen-lined ground squirrel, don’t sense the cold until lower temperatures than endotherms that don’t hibernate.”

“Many cold-climate endotherms exhibit torpor: a state of decreased activity. They look like they are sleeping. Because animals capable of torpor alternate between internally regulating their body temperature and allowing the environment to influence it, scientists consider them heterotherms.”

Most people will acknowledge these are interesting words. But when summarizing the information, they will skip using them and go back to using simpler, more familiar language. Often the thought is that these words are too tough for children to remember (especially if the adult doesn’t really understand what they mean). What if instead of skipping using them, we investigated them further? What if we looked closer at the sense, the meaning and the function of the morphemes in each of these words? We have here an opportunity to understand scientific terminology AND word families better!

hypothermia

Let’s begin by looking at <hypothermia>. It was first attested in 1877 and is from Modern Latin. When something is noted as being Modern Latin, that means that the word was created by scientists who needed a name for something. They didn’t just make up a name, but rather they looked back to Latin and Greek for what to call it. The word <hypothermia> did not exist in Greek, but the stems <hypo> “under” and <therm> “heat” did. The <-ia> suffix indicates that this word is an abstract noun. If you look at the denotation of the base <therm> “heat” and the denotation that the base <hypo> “under” has, you can see that the word itself tells you that hypothermia is when something is under it’s normal level of heat. If a person has hypothermia, their body temperature is lower than it should be. The base <therm> is from Greek θερμός (transcribed as thermos).

What about this base <hypo>? It is from Greek ύπό (transcribed as hypo) and has a denotation of “under.” Have we seen this in other familiar words? What about a hypothesis, which is the groundwork for an investigation. Do you recognize the denotation of “under” in hypothesis, as in an underlying position? It is also in hypodermic, which is the area just under the skin. That gives you a better sense of where a hypodermic needle is used, doesn’t it? And what about hypotenuse, which is the side of a triangle that is opposite the right angle. It has a sense of being stretched under the right angle.

endotherms

When I looked for <endotherms>, I was lead to <endothermic>. Etymonline notes that this word was first attested in 1866 and was formed by adding <endo-> and <thermal>. The suffix <-ic> indicates that the word is an adjective. The suffix <-al> can indicate the same thing. When I look at the entry for <thermal>, I learned that the first time it was used to mean “a sense of heat” was in 1837. So using <-al> is older than the use of <-ic> with this base.

So what about the base <endo->? It is from Greek ένδον (transcribed as endon) and has a sense of “inside, internal”. When you pair up <endo> “internal” and <therm> “heat”, you can see that the word itself tells you that endotherms are organisms that regulate their heat from inside themselves.

We see this base in endoscopy which is when a doctor uses a camera and light attached to a flexible tube to examine your esophagus, stomach, and/or intestines. In other words, the doctor is looking at your internal organs.

This base is also in endoskeleton which is the internal skeleton structure that all vertebrates have.

My dogs are endotherms. So am I.

ectotherms

There was not a specific entry for <ectotherms> at Etymonline, but there was an entry for <ecto->. It is from Greek έκτός (transcribed as ecktos) and has a denotation of “outside, external.” It is related to the prefix <ex-> “out”, but they are not the same. When you pair up <ect> “outside” with <therm> “heat”, you can see that the word itself tells you that ectotherms are organisms whose body heat is regulated by their environment (outside themselves).

I went to the Oxford English Dictionary (OED) to find related words. This base is found in science words like ectotrophic. An example of that is when tissues form on the outside of a root and are being nourished by that root. Interestingly enough, the opposite of ectotropic is endotrophic! That is when one organism is getting nourishment from within another organism.

We also see this base in ectocrine which is described as an organic substance that is released from the outer layer of an organism that will effect other organisms in the environment in either a good or bad way. It will come as no surprise to you that this word is the opposite of endocrine, which is a gland having an internal secretion. So in one case the secretion is external, and in the other it is internal.

Turtles and snakes are ectotherms. They bask in the sun to get heat.

heterotherms

There wasn’t a specific entry for <heterotherms> at Etymonline, but there was an entry for <hetero->. It comes from Greek ’έτερος (transcribed as heteros) with a denotation of “one of two”. When you pair up <heter> “one of two” with <therm> “heat”, you can see that the word itself tells you that heterotherms are animals that can regulate their own heat AND also have their heat regulated by their environment. Here’s something interesting that I found at Wikipedia:

“Regional heterothermy describes organisms that are able to maintain different temperature “zones” in different regions of the body. This usually occurs in the limbs, and is made possible through the use of counter-current heat exchangers, such as the rete mirabile found in tuna and certain birds. These exchangers equalize the temperature between hot arterial blood going out to the extremities and cold venous blood coming back, thus reducing heat loss. Penguins and many arctic birds use these exchangers to keep their feet at roughly the same temperature as the surrounding ice. This keeps the birds from getting stuck on an ice sheet.”

“Chinstrap Penguin with snow in its mouth” by Liam Quinn is licensed under CC by-sa 2.0

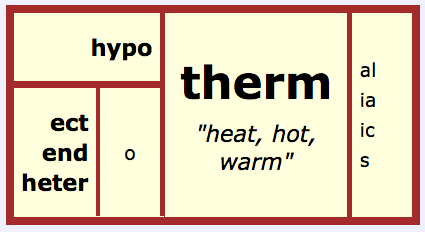

Here is a matrix of the words we have looked at:

You will notice that all the base elements are bolded. The connecting vowel <o> and the suffixes are not. That means that there are four compound words represented on this matrix:

<hypothermia –> hypo + therm + ia>

(or variations such as hypothermic or hypothermal)

<ectothermal –> ect + o + therm + ic>

(or variations such as ectotherm or ectotherms)

<endotherms –> end + o + therm + s>

(or variations such as endotherm or endothermic)

<heterotherm –> heter + o + therm>

(or variations such as heterotherms or heterothermal)

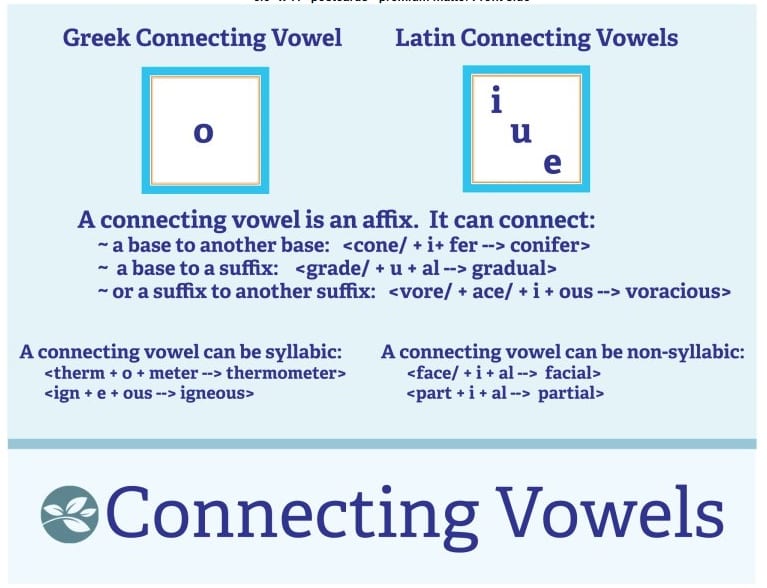

You may not be familiar with a connecting vowel, so let me explain a bit about them. They are used to connect two bases (as they are doing in three of the four words above), but they can also connect a base to a suffix or a suffix to another suffix.

My favorite example of a compound word with an obvious connecting vowel is <speedometer>. We instantly recognize the two bases here because they are both free bases. We also recognize that the <o> doesn’t belong to either one! It is simply connecting them. The <o> can be used because the second base <meter> is from Greek μέτρον (transcribed as metron) “measure”. The first base is not from Greek. It is from Old English sped. The sense and meaning “rate of motion or progress” is from c.1200. The fact that one of the bases is from Greek and one is from Old English makes this word a Germanic hybrid!

Have you noticed that in the above matrix not all of the words have an <o> connecting vowel? How do I know that the <o> at the end of <hypo> is not a connecting vowel? I start by doing some research. If you skim back through the paragraphs in this post, you will find that the origins of the bases are as follows:

<therm> – Greek θερμός (transcribed as thermos)

<hypo> – Greek ύπό (transcribed as hypo)

<end> – Greek ένδον (transcribed as endon)

<ect> – Greek έκτός (transcribed as ecktos)

<heter> – Greek ’έτερος (transcribed as heteros)

Notice that three of the four have the same Greek suffix. That <os> suffix is called the nominative suffix. If I remove it, I see the stem that then came into English as a base. There is one word that has a Greek <on> genitive suffix. If I remove it, I see the stem that then came into English as a base. Those four bases entered English without the <o>. We can also notice that the words we’re looking at today were coined by scientists who needed a word to describe something they were working on. Oftentimes they joined the Greek (or Latin) bases (that fit best in the context of what they were doing) with a connecting vowel.

I know that <hypo> does not have a connecting vowel because it does not have a Greek suffix that could be removed. This present day base was a preposition in Greek. If you look in the OED, you can find several entries for <hypo> as a free base noun.

The bottom line

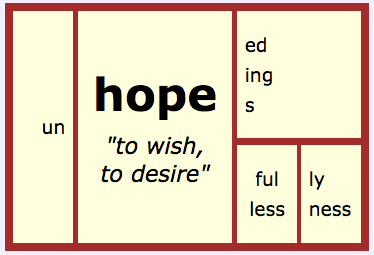

As you read through this post, I hope your sense of these bases deepened. When I do this with children, it’s not that I want them to remember every word we talk about. It’s more that I want them to take an invisible thread and connect each base or morpheme that we focus on to the words in which it is used. I want them to see that every word is not completely new and unique. Words belong to families, and the key to understanding an unfamiliar word is by recognizing one or more of its morphemes and being able to recall some related words to help with remembering the sense and meaning that the words share.

The matrix I created above focuses on the words from the article that had the base <therm> in common. The joy of matrices is that they can be used for what you need them to be used for. They don’t need to contain every possible word that shares the base (probably impossible anyway). I love when one of my students presents a matrix they made to the rest of the class and another student asks, “Could such and such a word be added to that matrix?” The person who created the matrix doesn’t have to feel embarrassed because they missed something. There is no expectation that a great matrix has x number of words! A word matrix is a starting point. It is a thought provoker and a discussion starter. When another student suggests a word that could be added, it proves that the students in the audience are engaged and thinking about this particular family. That is a thing to celebrate!

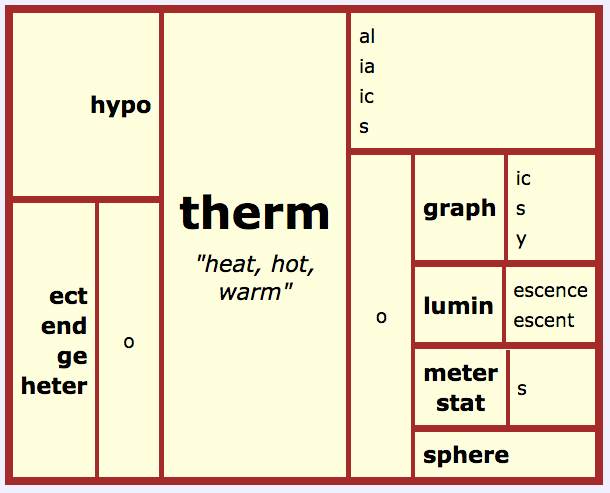

That being said, a fuller matrix is really fun to look at once in a while. Once you start thinking about this base <therm>, you start wondering what other words you know that share the base. Have fun thinking about the words represented below. Do you recognize the bases we just studied? Do you recognize the others? Are you familiar with the suffixes? Are you noticing that a connecting vowel is used to connect bases where <therm> is the second base? Are you noticing that a connecting vowel is used to connect bases where <therm> is the first base? Are you aware that any word that contains two or more bases is a compound word? Do you know the denotations of the bases I haven’t talked about?

I encourage you to use Etymonline as a starting point. Find out what the bases mean independently, and then find out how we currently use the word by looking in a modern dictionary. Sometimes I like to search for an image as well to further deepen my understanding. Notice how the connecting vowel is pronounced in thermographic, thermoluminescence, thermostat, and thermosphere. Then notice how there is a shift in stress, which changes the way we pronounce that connecting vowel in thermography and thermometer. Interesting, right? The pronunciation changes, but the spelling and the meaning does not. An orthographic truth you can count on!

A warm send off

Well, this here endotherm is going to put on thermal underwear so she doesn’t have to turn up the thermostat. I wish we had geothermal energy, but we don’t. Staying warm might prevent the need for a thermometer should she take a chill. Once she’s dressed in layers, she can gaze out the window and imagine that she can see all the way to the thermosphere.