This week I will be observing a lesson in a high school science class. The lesson will focus on naming ionic compounds. In preparation for this observation I asked to look over the reading materials the students will use. Having very little background in chemistry beyond that of what fifth grade students are expected to understand, I found words being used that I didn’t clearly understand. And, of course, knowing that if I want to increase my understanding of the lesson, I’ll need to understand the specific terminology, I did some word investigation.

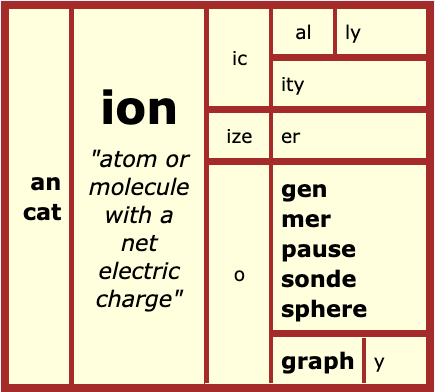

ion

At Etymonline I found out this.

The information tells us that this word was first attested in 1834. That means that the first time we have written evidence of this word existing is in 1834. And if you read further, you will see that it was coined by Michael Faraday on the suggestion by Rev. William Whewell and derived from the Greek word ion (ἰόν) which was a form of Greek ienai (ἰέναι) “go.” It is common to find scientific names for things attested from 1500 to present. During that time and in some cases even earlier, the Latin language was revived for scholarly and scientific purposes. This time period and the idea of coining words using stems derived from Latin and Greek is called Modern Latin. These words were coined in Modern Latin.

It is helpful to understand that the denotation of ‘ion’ is “go” because as it says at Etymonline, “ions move toward the electrode of opposite charge.” To see if I could find some more etymology, I went to the OED (Oxford English Dictionary). The word ‘ion’ is defined as either a single atom, molecule, or a group that has a net electric charge. It doesn’t matter whether that charge is positive or negative, only that that charge is a result of either the loss or addition of an electron. Next I set out to find some related words.

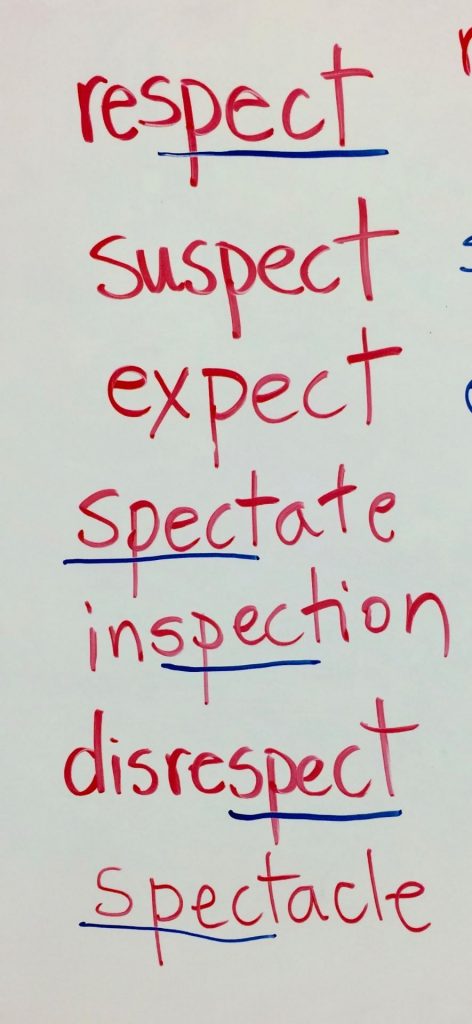

ionic – <ion + ic> “relating to or composed of ions.” adjective

ionically – <ion + ic + al + ly> “relating to or composed of ions.” adverb

ionicity – <ion + ic + ity> “the degree to which something is ionic.”

ionizer – <ion + ize + er> “a device that helps an air purifier be more effective.”

ionogen – <ion + o + gen> “a substance able to produce ions.”

ionography – <ion + o + graph + y> “a form of printing in which a static electric charge draws toner particles from the drum to the paper.”

ionomer – <ion + o + mer> “a polymer that contains ions.”

ionosphere – <ion + o + sphere> “layer of the atmosphere that contains a high level of ions and reflects radio waves.”

ionopause – <ion + o + pause> “the boundary layer of the ionosphere where it meets either the mesosphere at one side or the exosphere on its other.”

ionosonde – <ion + o + sonde> “special radar used to examine the ionosphere.”

cation – <cat + ion> “positively charged ion.”

anion – <an + ion> “negatively charged ion.”

You will notice that the only two words on my matrix that form a compound word with ‘ion’ being the second base are ‘anion’ and ‘cation’. A closer look at these two words brings with it many interesting finds!

anion

The Etymonline entry is interesting.

Notice that the word ‘anode’ is bolded. When I see that, I always follow such a word to find out more. In this case, I see that ‘anode’ is first attested in 1834. As is the case with ion, cation, anode, and cathode, the word was proposed by Rev. William Whewell and published by Michael Faraday. It’s pretty obvious that these two were needing to name components of what they were studying and finding! The first base is derived from Greek ana “up”, and the second base is derived from Greek hodos “way, path, track.”

According to Wikipedia, “An anode is an electrode through which the conventional current enters into a polarized electrical device. This contrasts with a cathode, an electrode through which conventional current leaves an electrical device.” This definition makes sense if we think about the literal translation of ‘anode’ as “up a path or way.” If ‘cathode’ is the electrode through which conventional current leaves an electrical device, then I’m guessing that the first base in ‘cathode’ must have a denotation of down. According to Etymonline, <cat> is indeed derived from Greek kata “down.” So in this case, as the current enters the device it is on its way up (anode), and when it leaves it is on its way down (cathode).

Back to ‘anion’. This word has a literal translation of “go up.” An anion has more electrons than protons, so it is negatively charged. You might say that the number of electrons is what “goes up” in an anion.

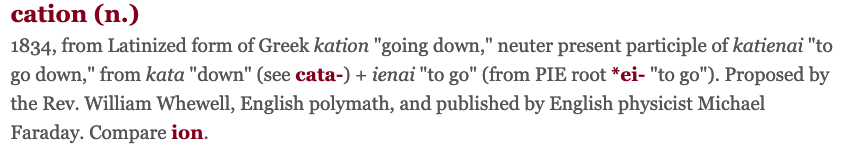

cation

Here is the Etymonline entry.

Are you noting the same year of attestation once again? And the same scientists who coined this word? Another interesting thing to note is written right after the date of attestation (1834). It says that ‘cation’ is from a Latinized form of Greek kation “going down.” It is a Latinized form because the Roman scribes wrote the Greek letter kappa as a <c>. Since we now know that an ‘anion’ has more electrons than protons and has a literal sense of “go up”, it makes sense to think of a cation as having less electrons than protons (positive charge). The number of electrons is what “goes down” in an cation.

A word about the pronunciation of anion and cation.

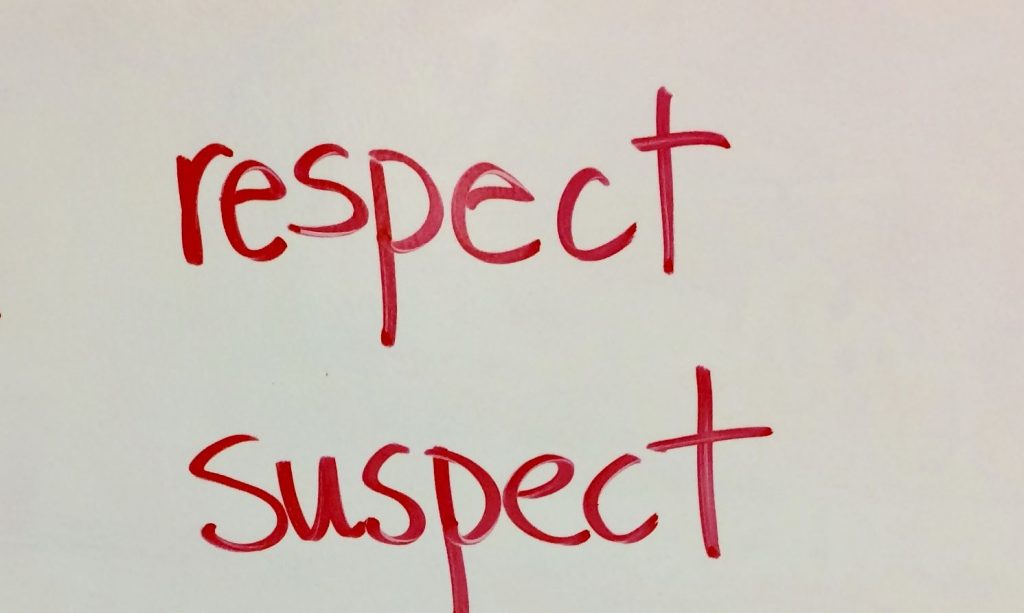

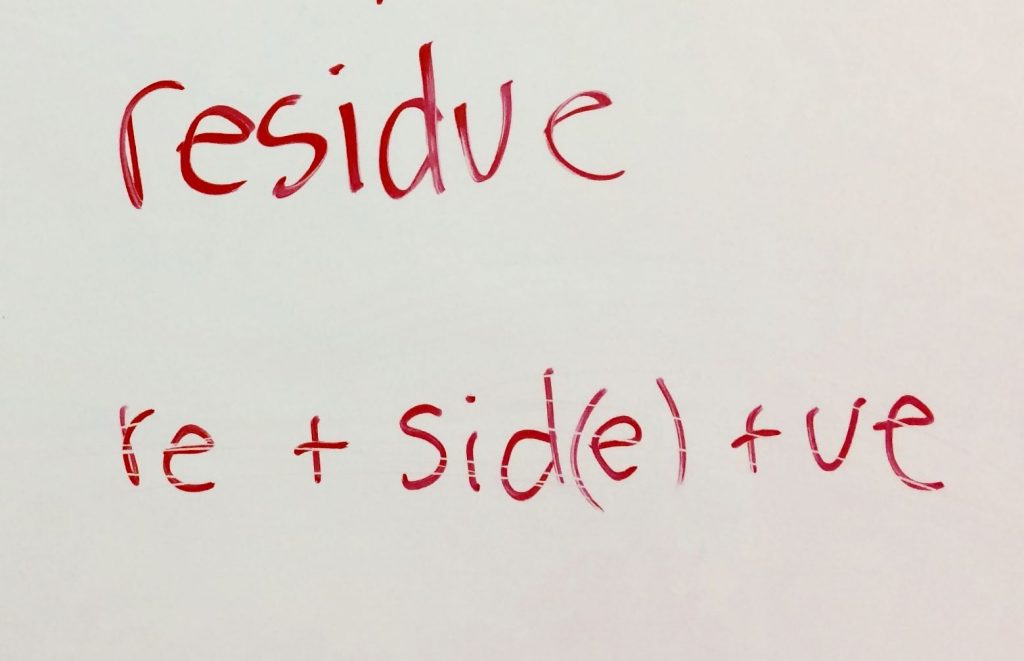

It might be tempting to pronounce ‘anion’ similarly to ‘onion’ and ‘cation’ to what we hear in the portmanteau word ‘staycation’. But we would only be tempted to do that because of the commonly used suffix <-ion>! When the <-ion> suffix is added to a word like ‘one’, we end up with ‘onion’. The IPA for the American pronunciation of ‘onion’ is /ˈʌnjən/. The IPA representation for ‘anion’ is /ˈænaɪən/. Compare this pronunciation to that of ‘ion’, /ˈaɪən/. Do you see what is similar? The <ion> base is pronounced differently than the <-ion> suffix! Let’s see if it is the same with ‘cation’. If we think of the pronunciation of ‘staycation’, we would represent it with IPA like this /steɪˈkeɪʃən/. But the IPA for the American pronunciation of ‘cation’ is /ˈkædˌaɪən/. If you compare this with the pronunciation of ‘ion’, you will once again notice that the base <ion> is not pronounced the same as the <-ion> suffix!

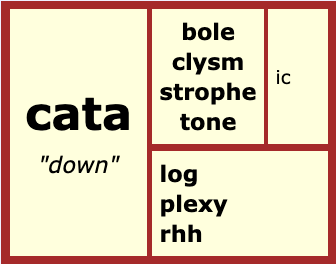

Where else do we see this Hellenic base <cat>?

cataclysm – <cata + clysm> “wash down.” Originally a flood, now a large-scale or violent event.

catalog – <cata + log> “list down.” Also spelled <catalogue>.

cataplexy – <cata + plexy> “strike down.” An example is when an animal pretends it’s dead.

catarrh – <cata + rrh> “flowing down.” It is inflammation and discharge from a head cold.

catastrophe – <cata + strophe> “turning down.” It is the reverse of what is expected.

catatonic – <cata + tone + ic> “toned down.” A mental illness in which the person is immobile in both movement and behavior.

catabolic – <cata + bole + ic> “thrown down.” According to Wikipedia it is the breaking-down aspect of metabolism.

There are other words that also have this Helenic base, and its sense and meaning isn’t just limited to “down.” I just included a few words with that specific sense so we could easily connect it to what we see in ‘cation’.

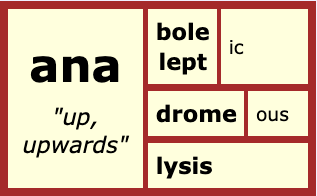

Where else do we see this Hellenic base <ana>?

anadromous – <ana + drome + ous> “running upward.” An example is fish going upstream to spawn. (The <drome> base “run” is the same as in ‘dromedary’)

analeptic – <ana + lept + ic> “take up.” A drug that restores your health.

analysis – <ana + lysis> “loosen up.” A loosening of something complex into smaller segments.

anabolic – <ana + bole + ic> “thrown up.” According to Wikipedia it is the building-up aspect of metabolism.

Like <cata>, <ana> isn’t just limited to one sense and meaning. I chose words with this base and this sense so we could more easily see the connections to ‘anion’.

I always find it helpful to collect more information about words I’ve heard, but am not completely familiar with. When I saw similar words like anode and anion, and also cathode and cation, I knew that I would need to understand both bases in each of these compound words in order to keep their meanings straight. I’ve learned that the second base in ‘anode’ and ‘cathode’ has to do with a path or track. An anode is the electrode through which the electrical current enters a polarized electrical device, and a cathode is the electrode through which the current leaves. I’ve learned that the second base in ‘anion’ and ‘cation’ has to do with movement. An anion has more electrons than protons and is negatively charged. A cation has more protons than electrons and is positively charged.

Knowing that <ana> has a denotation of “up” helps me picture an arrow pointed up indicating that the number of electrons is higher than that of the protons in an anion. Knowing that <cata> has a denotation of “down” helps me picture an arrow pointed down, indicating that the number of electrons is lower than that of the protons in an cation.

Now I feel better prepared to learn about naming ionic compounds.