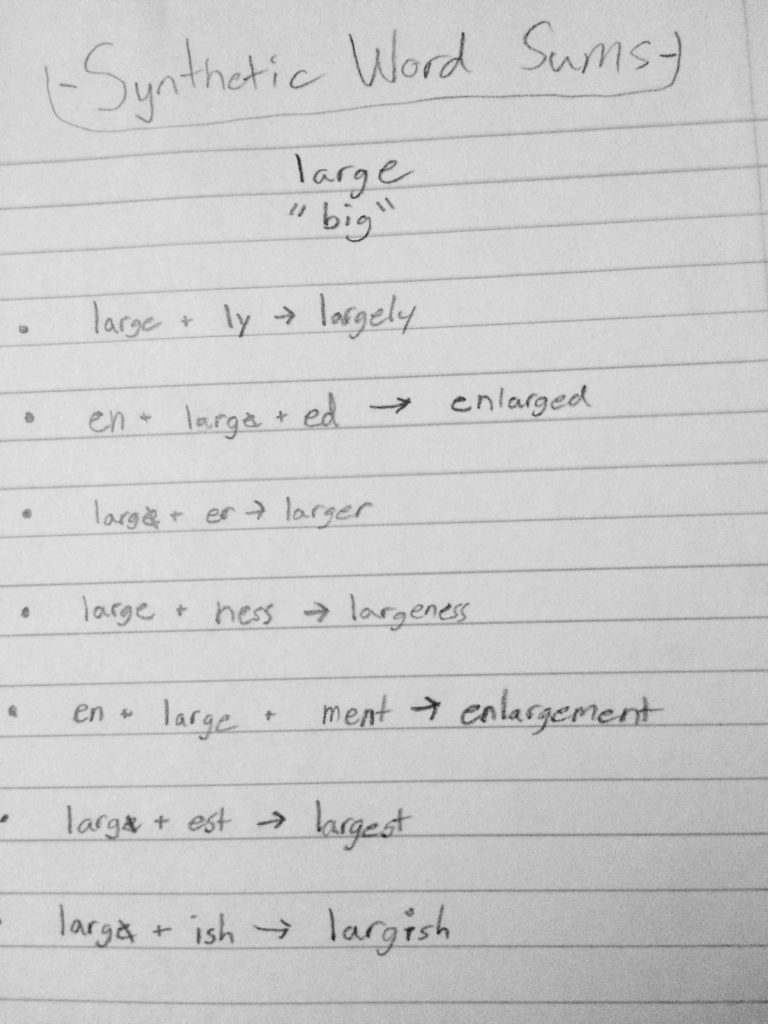

On Friday I chose the word ‘large’. I wrote it on the board with a denotation of “big” underneath. I read seven words, using each in a sentence so the student wouldn’t have to rely on my isolated pronunciation alone. They heard it in context and that helped with understanding its meaning and grammatical use.

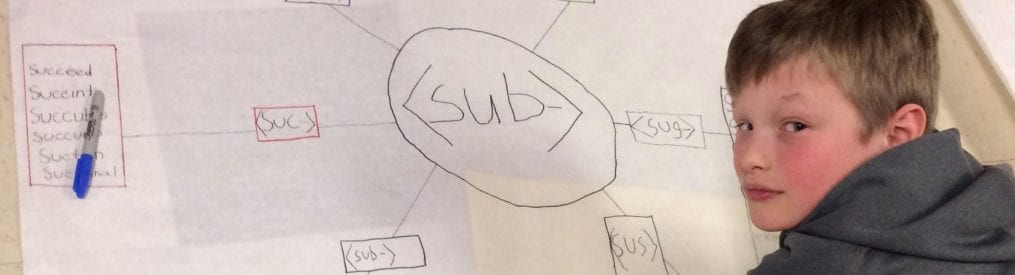

I asked the students to write either a synthetic word sum or an analytic word sum on their paper for each word.

After I collected the papers, the students volunteered to write their word sum on the board. If there was a question about any of them, it was asked and explained by fellow students before we went on to announce the word sums.

The following video is an example of the way students announce and explain word sums. It was taken on a different day with a different base, but gives you the idea of what I mean by “announcing the word sum.”

When I looked at the collected papers over the weekend, I noticed that very few recognized an <en-> prefix. Most assumed it was an <in-> prefix. But why wasn’t it an <in-> prefix? That is something I never thought about before!

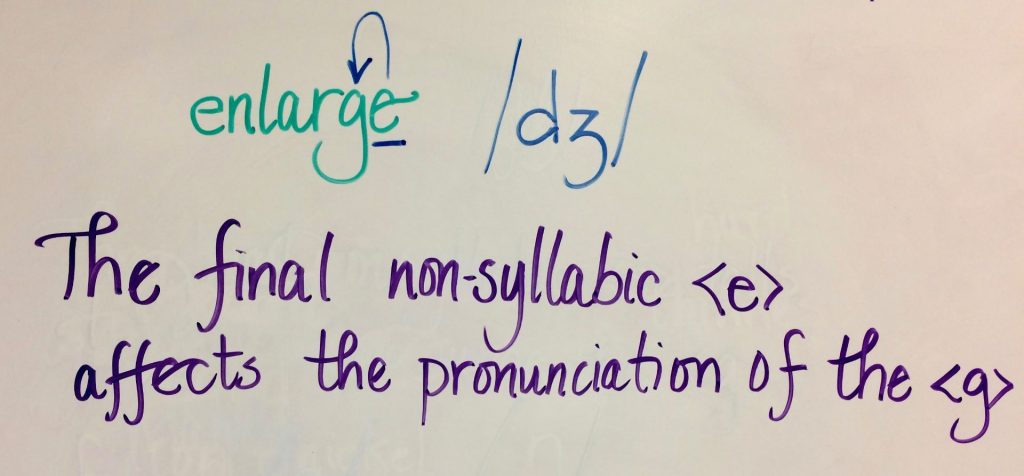

So today I started class with the word ‘enlarged’ on the board. My first question to the students was, “Why is there a final non-syllabic <e> here? What is its job in this word?” My second question was, “Why is the prefix an <en-> and not an <in->? What followed was so delightful that I just had to share by writing this post!

Why is there a final non-syllabic <e> in <enlarge>?

I called on Tyler, and he said, “Well, I have two ideas. It might be there so we know how to say the <a>, or else it might be there so we say /dʒ/ at the end.”

“Interesting.” I spoke to the rest of the class. “What do you think about what Tyler just said?”

“I agree that the <g> is pronounced /dʒ/ if the <e> is there.”

So I asked for some words that have a final <g>. I wanted them to compare the pronunciation of a final <g> in a word to a final <ge>. Some of the suggested words were flag, frog, dog, and drag. The difference in pronunciation (/g/ in flag and /dʒ/ in large) was quite noticeable.

Next I had them pull out their orthography notebooks and turn to the page where we are keeping track of the different jobs a final non-syllabic <e> might have. We added that a final non-syllabic <e> can affect the pronunciation of the preceding letter <g>.

Then we went back to address Tyler’s other idea. “Is it possible that this <e> is also affecting the pronunciation of the <a> in this word?”

A student responded with, “I don’t think so.”

I asked, “Can you name a word where the final non-syllabic <e>is clearly affecting the pronunciation of the previous vowel?”

The student replied with “Cake. The <a> in enlarge is not being pronounced like the <a> in cake.”

Excellent. Time to move on to my second question to the class.

Why is the prefix an <en-> and not an <in->?

First off I stopped and thanked everyone. “If so many of you hadn’t used <in-> instead of <en->, I wouldn’t have questioned it. I knew this prefix was <en-> because I knew the word and its spelling. Until this weekend, I never thought to stop and wonder why it isn’t <in->. Don’t ever forget. You aren’t the only ones learning about words in this classroom. I am learning with you. I constantly learn interesting stories that I wouldn’t have found without the questions being asked, the analysis being wondered about, or without the mistakes being made! We are in this together!”

Then we went to Etymonline and looked at ‘enlarge’. Fascinating. This word was first attested in the mid-14th century. At that time it meant “grow fat, increase”. We stopped and noted that we still use it to mean that. Then we kept reading. It was borrowed from Old French enlargier, enlargir “make large” (en- make + large large). How interesting that the word itself meant (and still does) “make large”! I noticed that in the entry, the <en-> was bolded, so I clicked on it to learn more about the <en-> prefix.

It means “in; into” and is from French and Old French <en->. (We recognized that ‘enlarge’ had been from Old French. We knew we were looking at the same <en->.) Before that it was borrowed from Latin <in-> “in, into”! What do you know? Reading further we found out that Latin <in-> became <en-> in French, Spanish, and Portuguese. It remained <in-> in Italian.

“I wonder if Sarah knows the Italian word for ‘enlarge’ and if it begins with an <in-> prefix,” a few asked all at once. (We are fortunate to have a student who moved from Italy to the United States just before school started. She knew a little English, but not very much). Sarah has been loving our word studies and when I saw her in the next class, I asked her about the Italian word similar to the English word ‘enlarge’. She wrote on the board:

I asked, “Who understands how this word is similar to enlarge?”

Right away a bunch of hands went up. “I see ‘grand’ in there. Something that is grand (like a grand prize) is big!” How cool! Three months ago, they would not have seen that. They are looking at words in a new way. They are looking, expecting to see something that will make sense! I love it!

At the bottom of the page there was a tab that said, “See all related words (126)”. How common is the <en-> prefix we wondered?

What a treasure trove! Students read out the words that were familiar — words like enact, embrace, and empower. The fact that in some words the <en-> has assimilated to <em-> was not earthshaking. We continually run into assimilated prefixes and talk about them. We moved on to page two. On this page they spotted encourage, enjoy, endanger, engage, and yes, enlarge! A few had questions about what some of the words meant.

Then Ella asked about energy. “What would the word sum for energy be?” she wondered.

“Thank you for that brilliant question,” I responded. “You are thinking like an orthographer!”

Because the word was on this list, we wrote the following word sum hypothesis with <en-> as a prefix:

<en + erg + y>

Then I had a student look it up in my Chambers Dictionary of Etymology. We found that it was borrowed from Middle French énergie. Before that it was borrowed directly from Late Latin energia, and before that it was from Greek enérgeia “activity, orperation” (en- “in” + érgon “work”).

Rylee asked what other words have this <erg> base. At Etymonline I found ergonomics – “the study of the efficiency of people in the work place” as well as ergophobia – “the fear of work”!

Ella’s hand went up again. “What would the word sum for environment be?” I smiled big.

“Great question! What do you think it would be? Do you see a prefix you recognize? Do you see a suffix you recognize?”

Ella offered this: <en- + viron + ment>. We looked it up. We found out that the noun ‘environment’ is not as old as the verb ‘environ’, which was first attested in the late 14th century. The base is <viron> and has a denotation of “circle”. So an environment is a surrounding area, an area that is encircled.

I threw in that I had learned over the weekend (Scholarship Sunday) that many words with an <-ment> suffix are abstract nouns. The word ‘environment’ certainly fit that. There was an interesting discussion about this word. Couldn’t you go out into the environment and touch it? Wouldn’t that make it a concrete noun? Hmmm. Could you really touch the environment, or could you touch only a component of the environment? In the end it was decided that environment was indeed an abstract noun. Other words with an <-ment> suffix were suggested such as argument, comment, and government. These were certainly abstract nouns. What an interesting thing to keep in mind as we continue investigating and thinking about words!

We continued looking through the list of words related to <en-> at Etymonline. The best was the last word listed – ‘ink’. The immediate question was, “Would the word sum be <in- + k>?”

“Let’s revisit your question after we read a bit.”

I was able to introduce Samuel Johnson as the entry began with his definition of ink as, “The black liquor with which men write.” I wondered if liquor had a different sense then, so I looked in his dictionary and found that he defined liquor as “anything liquid”. He was quite an interesting dictionary writer! In case you are unfamiliar with Samuel Johnson, he published his dictionary in 1755. It took him 7 years to complete. Other dictionaries that existed at the time tended to include words considered to be hard and/or hardly used. His dictionary focused on the words in use at the time and on the way they were used. It was considered THE dictionary until the Oxford English Dictionary was published.

Besides that, we noticed that where the rest of these related words began with an <in> that later became <en>, this word began with the <en> spelling and in PDE has an <in>! It began as Old French enche, encre. Prior to that it was from Late Latin encaustum, and prior to that it was borrowed from Greek enkauston. What was so interesting was the denotation of the Hellenic etymon kaiein “burn”. We’re talking about ink, right? What does an etymon meaning “burn” have to do with it?

Well, it seems that this is referring to a purple-red ink used by the Greek and Roman emperors for their signatures that was prepared with heat. Etymonline states, “It was the name of the purple-red ink, the sacrum encaustum, used by the Roman emperors to sign their documents; this was said to have been obtained from the ground remains of certain shellfish, formed into writing fluid by the application of fire or heat, which explained the name. In the Code of Justinian, the making of it for common uses, or by common persons, was prohibited under penalty of death and confiscation of goods.”

Wow. We tried to imagine how a liquid could be obtained in this manner! Or why people would even try to make it if the punishment was so severe!

It was time to revisit the question, “Would the word sum for ink be <in- + k>?” After having read and discussed the entry, the student didn’t think so. There wasn’t any evidence of a <k> base. But boy, oh, boy! What an interesting story!

This is how learning about our language can go. One day you plan something to do, and because of what gets noticed during the course of your plan, several other learning opportunities appear. It is all good, of course, but the unplanned discoveries are the best! We all (teacher included) leave the room smiling.